Swati-Janu-The-River-And-The-City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Statistics of Delhi

BASIC STATISTICS OF DELHI Page No. 1. Names of colonies/properties, structures and gates in Eighteenth Century 2 1.1 Sheet No.1 Plan of the City of Delhi 2 1.2 Sheet No.2 Plan of the City of Delhi 2 1.3 Sheet No.5 Plan of the City of Delhi 3 1.4 Sheet No.7 Plan of the City of Delhi 3 1.5 Sheet No.8 Plan of the City of Delhi 3 1.6 Sheet No.9 Plan of the City of Delhi 3 1.7 Sheet No.11 Plan of the City of Delhi 3 1.8 Sheet No.12 Plan of the City of Delhi 4 2. List of built up residential areas prior to 1962 4 3. Industrial areas in Delhi since 1950’s. 5 4. Commercial Areas 6 5. Residential Areas – Plotted & Group Housing Residential colonies 6 6. Resettlement Colonies 7 7. Transit Camps constructed by DDA 7 8. Tenements constructed by DDA/other bodies for Slum Dwellers 7 9. Group Housing constructed by DDA in Urbanized Villages including on 8 their peripheries up to 1980’s 10. Colonies developed by Ministry of Rehabilitation 8 11. Residential & Industrial Development with the help of Co-op. 8 House Building Societies (Plotted & Group Housing) 12. Institutional Areas 9 13. Important Stadiums 9 14. Important Ecological Parks & other sites 9 15. Integrated Freight Complexes-cum-Wholesale markets 9 16. Gaon Sabha Land in Delhi 10 17. List of Urban Villages 11 18. List of Rural Villages 19. List of 600 Regularized Unauthorized colonies 20. -

The Trajectory of a Struggle

SSHAHRIHAHRI AADHIKARDHIKAR MMANCH:ANCH: BBEGHARONEGHARON KKEE SSAATHAATH ((URBANURBAN RRIGHTSIGHTS FFORUM:ORUM: WWITHITH TTHEHE HHOMELESS)OMELESS) TTHEHE TTRAJECTORYRAJECTORY OOFF A SSTRUGGLETRUGGLE i Published by: Shahri Adhikar Manch: Begharon Ke Saath G-18/1 Nizamuddin West Lower Ground Floor New Delhi – 110 013 +91-11-2435-8492 [email protected] Text: Jaishree Suryanarayan Editing: Shivani Chaudhry and Indu Prakash Singh Design and printing: Aspire Design March 2014, New Delhi Printed on CyclusPrint based on 100% recycled fibres SSHAHRIHAHRI AADHIKARDHIKAR MMANCH:ANCH: BBEGHARONEGHARON KKEE SSAATHAATH ((URBANURBAN RRIGHTSIGHTS FFORUM:ORUM: WWITHITH TTHEHE HHOMELESS)OMELESS) TTHEHE TTRAJECTORYRAJECTORY OOFF A SSTRUGGLETRUGGLE Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Objective and Methodology of this Study 2 2. BACKGROUND 3 2.1 Defi nition and Extent of Homelessness in Delhi 3 2.2 Human Rights Violations Faced by Homeless Persons 5 2.3 Criminalisation of Homelessness 6 2.4 Right to Adequate Housing is a Human Right 7 2.5 Past Initiatives 7 3. FORMATION AND GROWTH OF SHAHRI ADHIKAR MANCH: BEGHARON KE SAATH 10 3.1 Formation of Shahri Adhikar Manch: Begharon Ke Saath (SAM:BKS) 10 3.2 Vision and Mission of SAM:BKS 11 3.3 Functioning of SAM:BKS 12 4. STRATEGIC INTERVENTIONS 14 4.1 Strategies Used by SAM:BKS 14 4.2 Intervention by SAM:BKS in the Suo Moto Case in the High Court of Delhi 16 4.3 Media Advocacy 19 4.4 Campaigns of SAM:BKS for Facilitating Access to Entitlements and Realisation of Human Rights 20 5. THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA AND THE ISSUE OF HOMELESSNESS 22 5.1 Role of the Offi ce of Supreme the Court Commissioners in the ‘Right to Food’ Case 22 6. -

Rashtrapati Bhavan and the Central Vista.Pdf

RASHTRAPATI BHAVAN and the Central Vista © Sondeep Shankar Delhi is not one city, but many. In the 3,000 years of its existence, the many deliberations, decided on two architects to design name ‘Delhi’ (or Dhillika, Dilli, Dehli,) has been applied to these many New Delhi. Edwin Landseer Lutyens, till then known mainly as an cities, all more or less adjoining each other in their physical boundary, architect of English country homes, was one. The other was Herbert some overlapping others. Invaders and newcomers to the throne, anxious Baker, the architect of the Union buildings at Pretoria. to leave imprints of their sovereign status, built citadels and settlements Lutyens’ vision was to plan a city on lines similar to other great here like Jahanpanah, Siri, Firozabad, Shahjahanabad … and, capitals of the world: Paris, Rome, and Washington DC. Broad, long eventually, New Delhi. In December 1911, the city hosted the Delhi avenues flanked by sprawling lawns, with impressive monuments Durbar (a grand assembly), to mark the coronation of King George V. punctuating the avenue, and the symbolic seat of power at the end— At the end of the Durbar on 12 December, 1911, King George made an this was what Lutyens aimed for, and he found the perfect geographical announcement that the capital of India was to be shifted from Calcutta location in the low Raisina Hill, west of Dinpanah (Purana Qila). to Delhi. There were many reasons behind this decision. Calcutta had Lutyens noticed that a straight line could connect Raisina Hill to become difficult to rule from, with the partition of Bengal and the Purana Qila (thus, symbolically, connecting the old with the new). -

Water Meters Dealers List 19 MAY.Xlsx

DASMESH, DMB Meters. Sr.No. Zone/Area Name Address Contact 1 Central Delhi Chamanlal& Sons 3343, GaliPipalMahadev, HauzQazi, Delhi-110006 011 23270789 2 Central Delhi Mahabir Prasad & Sons 3702, CHAWRI BAZAR, DELHI-110006 011 23263351, 23271750 3 Central Delhi Motilal Jain & Co 3622, Chawri Bazar, Delhi-110006 011 23916843 4 Central Delhi Munshi Lal Om Prakash 3685, Chawri bazar, Delhi-110006 011 32637998, 23265692, 5 Central Delhi SS Corporation 3377, HauzQazi, Delhi-110006 011 23267697 6 Central Delhi Patwariji Agencies Pvt Ltd Shop no. 3314-15, Bank Street, Karol Bagh, Delhi - 011 28723231 110005, Near Karol Bagh Police Station 7 Central Delhi Veenus Enterprises 3852 GaliLoheWali, Chawari Bazar, Delhi 110006 011 23918006 8 East Delhi Raj Trading Company S505, School Block, Shakar Pur, Laxmi Nagar, Delhi- 9871501108 110092 9 East Delhi Vijay Sanitory Store 25/1, G.T. Road, Shadhara, Delhi-110032 22323040, 22323041, 9811060625 10 East Delhi Shri Krishna Paints 3-A., I Pocket., Mangal bazar road, Dilshad Garden, 011 22579456 Delhi-110095 11 East Delhi Sharma Water Supply Co. A-1, Jagat Puri, Shahdara, Delhi-110032 011 22123218 12 North Delhi Giriraj Tiles & Sanitary Empurium A-4/161, Sector 4, Rohini, Delhi - 110085 011 27044107 13 North Delhi Goel Sanitary Store Wp-466, Shiv Market, Wazirpur, Delhi - 110052 9810458161 14 North Delhi Raj Paints & Hardware Store 59, Main Bazar, Kingsway Camp, Delhi-110059 011 27214437 15 North Delhi Veer Sanitary Store C-10, Main Gt Road, Rana Pratap Bagh, Delhi - 110007 011 27436425 16 North DelhiRajilal& Sons 678, Main Bazar, SabziMandi, Delhi-110007 9818854021, 23857240 17 South Delhi Arora Paint & Hardware 1663/D-17, Main Road Kalkaji, Govindpuri, New Delhi- 011 26413291, 110019 6229797 18 South Delhi Durga Sanitary Paint & Hardware B-34-B, Main Road, Kalkaji, Delhi - 110019, Near 011 26225566, Store SagarRatna 41050909 19 South Delhi Kalka Sanitary Store A-57, Double Storey, Main Road, Kalkaji, Delhi - 110019, 011 26430433, Opposite HDFC Bank 26439474 9810094018 20 South Delhi Lakshmi Steel Sanitary & Shop No. -

Centrespread Centrespread 15 JULY 30-AUGUST 05, 2017 All the JULY 30-AUGUST 05, 2017

14 centrespread centrespread 15 JULY 30-AUGUST 05, 2017 All The JULY 30-AUGUST 05, 2017 takes you through ET Magazine Presidents’On Tuesday, Ram Nath Kovind moved in as the 14th President Houses to occupy Rashtrapati Bhawan, the official residence of the Indian President. the history and the peoplepresidential behind palacesthe palatial around residence, the world: and a glimpse into other :: Indulekha Aravind Presidential Residences Around The World ELYSEE PALACE, PARIS The official residence of the President of Rashtrapati Bhawan: A Brief History France since 1848, Elysee Palace was opened Cast Of Characters the building to move construction materials and subsoil water in 1722. An example of the French Classical pumped to the surface for all water requirements. style, it has 356 rooms spread over Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker 11,179 sq m n 1911, during the Delhi Durbar, it was decided that British The bulk of the land belonged to the then-maharaja of Jaipur, were the architects of the Viceroy’s India’s capital would be shifted from Calcutta to Delhi. With Sawai Madho Singh II, who gifted the 145-ft Jaipur Column to House and it was Lutyens who conceived THE WHITE HOUSE, the new capital, a new imperial residence also had to be the British to commemorate the creation of Delhi as the new the H-shaped building I WASHINGTON DC found. The original choice was Kingsway Camp in the north but capital. Though the initial idea was to finish the construction The home of the US President is spread it was rejected after experts said the region was at the risk of in four years, it finally took more than 17 years to complete, across six levels, with 132 rooms The main building was constructed under the supervision of flooding. -

Question. Which Is the Oldest Stadium in India

Weekly MCQs 27th November to 4th December Daily Current Affairs @7:30AM Live International News ➢ QS Asia University Rankings 2021: For the continent’s best higher education institutions ▪ The top-10 list doesn’t feature any Indian university. The top three Indian universities to feature on the Asia Rankings are IIT Bombay (Rank 47), IIT Delhi (Rank 50), and IIT Madras (Rank 56). ▪ A total of 107 Indian institutes made it to the overall QS Asia Rankings. Of them, 7 bagged a spot in the top 100. Daily Current Affairs @7:30AM Live International News ➢ QS Asia University Rankings 2021: For the continent’s best higher education institutions ➢ Top 5 University ▪ Rank 1:National University of Singapore (NUS), Singapore ▪ Rank 2: Tsinghua University, China (Mainland) ▪ Rank 3: Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore ▪ Rank 4: University of Hong Kong (HKU), Hong Kong SAR ▪ Rank 5: Zhejiang University, China (Mainland) Daily Current Affairs @7:30AM Live International News ➢ Global Terrorism Index (GTI) 2020: By Institute for Economics & Peace, is a global think tank headquartered in Sydney, Australia ▪ India has been ranked at 8th spot globally in the list of countries most affected by terrorism in 2019. ▪ With a score of 9.592, Afghanistan has topped the index as the worst terror impacted nation among the 163 countries. ▪ It is followed by Iraq (8.682) and Nigeria (8.314) at second and third place respectively. Daily Current Affairs @7:30AM Live International News ➢ New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern declared a climate emergency, telling parliament that urgent action was needed for the sake of future generations. -

Slum Rehabilitation in Delhi

WHOSE CITY IS IT ANYWAY? KRISHNA RAJ FELLOWSHIP PROJECT Madhulika Khanna, Keshav Maheshwari, Resham Nagpal, Ravideep Sethi, Sandhya Srinivasan August 2011 Delhi School of Economics 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank our professor, Dr. Anirban Kar, who gave direction to our research and coherence to our ideas. We would like to express our gratitude towards Mr. Dunu Roy and everyone at the Hazards Centre for their invaluable inputs. We would also like to thank all our respondents for their patience and cooperation. We are grateful to the Centre for Development Economics, Delhi School of Economics for facilitating our research. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 2. POLICY FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................................................... 2 2.1. SLUM POLICY IN DELHI ............................................................................................................ 2 2.2. SLUM REHABILITATION PROCESS ........................................................................................... 4 2.2.1. IN-SITU UP-GRADATION .................................................................................................. 4 2.2.2. RELOCATION.................................................................................................................... 4 3. RIGHTS AND CITIZENSHIP ............................................................................................................... -

The Challenge of “Human” Sustainability for Indian Mega-Cities: Squatter Settlements, Forced Evictions and Resettlement & Rehabilitation Policies in Delhi

V. Dupont Do not quote without the author’s permission Paper presented to: XXVII IUSSP International Population Conference Busan, Corea, 26-31 August 2013 Session 282: The sustainability of mega-cities The challenge of “human” sustainability for Indian mega-cities: Squatter settlements, forced evictions and resettlement & rehabilitation policies in Delhi Véronique Dupont Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (Institute of Research for Development) Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper deals with the “human” dimension of sustainability in Indian mega-cities, specially the issue of social equity approached through the housing requirements of the urban poor. Indian mega-cities are faced with an acute shortage in adequate housing, which has resulted in the growth of illegal slums or squatter settlements. Since the 1990s, the implementation of urban renewal projects, infrastructure expansion and “beautification” drives, in line with the requirements of globalising cities, have resulted in many slum demolitions, which increased the numbers of homeless people. Delhi exemplifies such trends. This paper’s main objective is to appraise the adequacy of slum clearance and resettlement and rehabilitation policies implemented in Delhi in order to address the challenge of slums. Do such policies alleviate the problem of lack of decent housing for the urban poor, or to what extent do they also aggravate their situation? It combines two approaches: firstly, a statistical assessment of squatters’ relocation and slum demolition without resettlement over the last two decades, completed by an analysis of the conditions of implementation of the resettlement policy; and, secondly, a qualitative and critical analysis of the recently launched strategy of in-situ rehabilitation under public- private partnership. -

Government Cvcs for Covid Vaccination for 18 Years+ Population

S.No. District Name CVC Name 1 Central Delhi Anglo Arabic SeniorAjmeri Gate 2 Central Delhi Aruna Asaf Ali Hospital DH 3 Central Delhi Balak Ram Hospital 4 Central Delhi Burari Hospital 5 Central Delhi CGHS CG Road PHC 6 Central Delhi CGHS Dev Nagar PHC 7 Central Delhi CGHS Dispensary Minto Road PHC 8 Central Delhi CGHS Dispensary Subzi Mandi 9 Central Delhi CGHS Paharganj PHC 10 Central Delhi CGHS Pusa Road PHC 11 Central Delhi Dr. N.C. Joshi Hospital 12 Central Delhi ESI Chuna Mandi Paharganj PHC 13 Central Delhi ESI Dispensary Shastri Nagar 14 Central Delhi G.B.Pant Hospital DH 15 Central Delhi GBSSS KAMLA MARKET 16 Central Delhi GBSSS Ramjas Lane Karol Bagh 17 Central Delhi GBSSS SHAKTI NAGAR 18 Central Delhi GGSS DEPUTY GANJ 19 Central Delhi Girdhari Lal 20 Central Delhi GSBV BURARI 21 Central Delhi Hindu Rao Hosl DH 22 Central Delhi Kasturba Hospital DH 23 Central Delhi Lady Reading Health School PHC 24 Central Delhi Lala Duli Chand Polyclinic 25 Central Delhi LNJP Hospital DH 26 Central Delhi MAIDS 27 Central Delhi MAMC 28 Central Delhi MCD PRI. SCHOOl TRUKMAAN GATE 29 Central Delhi MCD SCHOOL ARUNA NAGAR 30 Central Delhi MCW Bagh Kare Khan PHC 31 Central Delhi MCW Burari PHC 32 Central Delhi MCW Ghanta Ghar PHC 33 Central Delhi MCW Kanchan Puri PHC 34 Central Delhi MCW Nabi Karim PHC 35 Central Delhi MCW Old Rajinder Nagar PHC 36 Central Delhi MH Kamla Nehru CHC 37 Central Delhi MH Shakti Nagar CHC 38 Central Delhi NIGAM PRATIBHA V KAMLA NAGAR 39 Central Delhi Polyclinic Timarpur PHC 40 Central Delhi S.S Jain KP Chandani Chowk 41 Central Delhi S.S.V Burari Polyclinic 42 Central Delhi SalwanSr Sec Sch. -

Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2013 © 2013 Anuj Bhuwania All rights reserved ABSTRACT Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania This dissertation studies the politics of ‘Public Interest Litigation’ (PIL) in contemporary India. PIL is a unique jurisdiction initiated by the Indian Supreme Court in the aftermath of the Emergency of 1975-1977. Why did the Court’s response to the crisis of the Emergency period have to take the form of PIL? I locate the history of PIL in India’s postcolonial predicament, arguing that a Constitutional framework that mandated a statist agenda of social transformation provided the conditions of possibility for PIL to emerge. The post-Emergency era was the heyday of a new form of everyday politics that Partha Chatterjee has called ‘political society’. I argue that PIL in its initial phase emerged as its judicial counterpart, and was even characterized as ‘judicial populism’. However, PIL in its 21 st century avatar has emerged as a bulwark against the operations of political society, often used as a powerful weapon against the same subaltern classes whose interests were so loudly championed by the initial cases of PIL. In the last decade, for instance, PIL has enabled the Indian appellate courts to function as a slum demolition machine, and a most effective one at that – even more successful than the Emergency regime. -

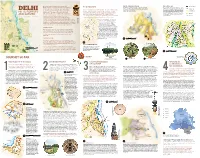

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

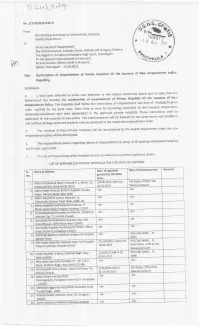

List of Empanelled Hospitals

a "[^: a , f \^ ' C- ft]^Y' t",l] Na. 21 27 6 | 2012-l H B-lll From Government, Haryana' /ff"u The Principal Secretary to Health DePartment. To t.,oW All the Heads of Departments \ Hissar, Rohtak and Gurgaon Division' R The Commissioners, Ambala, \^ The Registrar, Punjab and Haryana High Court' Chandigarh' \rl(qrr,xu All the Deputy Commissioners in Haryana ,r-y All Sub-Division Officer (Civil) in Haryana Dated Chandigarh 13'08.2015 the issuance of llew Empanelment policy- Sub:- Continuation of Empanelment of Private Hospitals till Regarding. Sir/Madam mentioned above and to state that the 2. l, have been directed to invite your attention to the subject Private Hospitalsi till the issuance of New Governmerlt has decided the continuation of ernpanelment of empanelment and that of Package/lmplant Ernpanelment Policy. The hospitals shall follow the instructions of treatment to the Haryana Government rates notified by the state Govt. from time to time for providing private hospitals' 'fhese instructions shall be employees/pensioners and their dependents in the approved be allowed on the same terms and conditions applicable till the issuance of new policy. The reimbursement will empanelment order' and notified package rates and implants rates as explained in the respective the Health Departrnent when the new 3. The renewal of these private Hospitals will be reconsidered by empanelment policy will be introduced' (2 years) of all existing empanelled hospitals 4. The empanelment orders regarding period of empanelment are hereby suPerseded. to continue is given as under:- 5. The list of Private Empanelled Hospitals which are aliowed L|sToFEMPANELLEDPR|VATEHOSP|TALSFoRTHESTATEoFHARYANA Remarks Date of aPProval Rate of reimbursement Sr.