1 Wireless Media Access Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEXT GENERATION MOBILE WIRELESS NETWORKS: 5G CELLULAR INFRASTRUCTURE JULY-SEPT 2020 the Journal of Technology, Management, and Applied Engineering

VOLUME 36, NUMBER 3 July-September 2020 Article Page 2 References Page 17 Next Generation Mobile Wireless Networks: Authors Dr. Rendong Bai 5G Cellular Infrastructure Associate Professor Dept. of Applied Engineering & Technology Eastern Kentucky University Dr. Vigs Chandra Professor and Coordinator Cyber Systems Technology Programs Dept. of Applied Engineering & Technology Eastern Kentucky University Dr. Ray Richardson Professor Dept. of Applied Engineering & Technology Eastern Kentucky University Dr. Peter Ping Liu Professor and Interim Chair School of Technology Eastern Illinois University Keywords: The Journal of Technology, Management, and Applied Engineering© is an official Mobile Networks; 5G Wireless; Internet of Things; publication of the Association of Technology, Management, and Applied Millimeter Waves; Beamforming; Small Cells; Wi-Fi 6 Engineering, Copyright 2020 ATMAE 701 Exposition Place Suite 206 SUBMITTED FOR PEER – REFEREED Raleigh, NC 27615 www. atmae.org JULY-SEPT 2020 The Journal of Technology, Management, and Applied Engineering Next Generation Mobile Wireless Networks: Dr. Rendong Bai is an Associate 5G Cellular Infrastructure Professor in the Department of Applied Engineering and Technology at Eastern Kentucky University. From 2008 to 2018, ABSTRACT he served as an Assistant/ The requirement for wireless network speed and capacity is growing dramatically. A significant amount Associate Professor at Eastern of data will be mobile and transmitted among phones and Internet of things (IoT) devices. The current Illinois University. He received 4G wireless technology provides reasonably high data rates and video streaming capabilities. However, his B.S. degree in aircraft the incremental improvements on current 4G networks will not satisfy the ever-growing demands of manufacturing engineering users and applications. -

Solutions to Chapter 2

CS413 Computer Networks ASN 4 Solutions Solutions to Assignment #4 3. What difference does it make to the network layer if the underlying data link layer provides a connection-oriented service versus a connectionless service? [4 marks] Solution: If the data link layer provides a connection-oriented service to the network layer, then the network layer must precede all transfer of information with a connection setup procedure (2). If the connection-oriented service includes assurances that frames of information are transferred correctly and in sequence by the data link layer, the network layer can then assume that the packets it sends to its neighbor traverse an error-free pipe. On the other hand, if the data link layer is connectionless, then each frame is sent independently through the data link, probably in unconfirmed manner (without acknowledgments or retransmissions). In this case the network layer cannot make assumptions about the sequencing or correctness of the packets it exchanges with its neighbors (2). The Ethernet local area network provides an example of connectionless transfer of data link frames. The transfer of frames using "Type 2" service in Logical Link Control (discussed in Chapter 6) provides a connection-oriented data link control example. 4. Suppose transmission channels become virtually error-free. Is the data link layer still needed? [2 marks – 1 for the answer and 1 for explanation] Solution: The data link layer is still needed(1) for framing the data and for flow control over the transmission channel. In a multiple access medium such as a LAN, the data link layer is required to coordinate access to the shared medium among the multiple users (1). -

The Application Layer Protocol Ssh Is Connectionless

The Application Layer Protocol Ssh Is Connectionless Deryl remains prognostic: she revile her misogamist clarified too ineffectually? Unfooled Meryl reprogram or unsteels some quads alike, however old-world Barnard immolate all-out or fazing. Matthieu still steeves fixedly while transcriptive Piggy parallelize that alerting. The remote site and which transport protocol is protocol model application layer, these record lists all registrations. As for maintaining ordered delivery. Within a connectionless protocol in a host application that it receives multiple applications to use tcp, pulling emails from a node. IP and MAC address is there. Link state algorithms consider bandwidth when calculating routes. Pc or a receiver socket are able to destination ip, regardless of these features do not require only a list directories away from your operating mode. Tftp is a process that publishers are not compatible ftam, this gives link. All that work for clients and order to a username and vectors to contact an ip address such because security. Ip operation of errors or was statically configured cost load. The application layer performs a set. Ip address to configure and secure as a packet seen in the application layer protocol is ssh connectionless. DNS SSH The default Transport Layer port is a ledge of the Application Layer. HTTP is a short abbreviation of Hypertext Transfer Protocol. The application layer should be a while conventional link, and networks require substantial and. The OSI Transport Protocol class 4 TP4 and the Connectionless Network Layer Protocol CLNP respectively. TCP IP Protocols and Ports Vskills. The parsed MIME header. The connectionless is connectionless. -

Manual Connect.Pdf

Wireless computer access at K-State Information Technology Services provides wireless access across campus for both the K-State community and for campus visitors. Instructions for connecting to KSU Wireless Windows XP configuration Windows Vista configuration Windows 7 configuration Macintosh OS 10.5x/6 configuration Android configuration iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch configuration HP Touch Pad configuration Chromebook configuration Ubuntu configuration Who can use K-State’s wireless network? 1. K-State faculty/staff and students should use “KSU Wireless”. 2. Residents in K-State residence halls and Jardine Apartments should use “KSU Housing”. 3. Campus visitors should use “KSU Guest”. What’s needed to connect to KSU Wireless? A computer with wireless network card A valid K-State eID/password How do I get help? Contact your departmental IT support staff or the K-State IT Help Desk (785-532-7722, helpdesk@k- state.edu). Windows XP configuration: KSU Wireless These instructions assume you are using the Windows management of the wireless network adapter. 1. Click the Start button in the bottom left corner of the desktop. (If you’re using the classic Windows start menu, click Settings.) Click Network Connections. Right-click Wireless Connections and select View Available Wireless Networks from the menu. OR: An alternative approach is to right-click the wireless networking icon in the bottom right corner of the Windows desktop. Select View Available Wireless Networks from the menu. 2. The Wireless Network Connection window will appear. 3. Click Change the order of preferred networks in the left-hand menu. The following window will appear. -

Chapter 2. Application Layer Table of Contents 1. Context

Chapter 2. Application Layer Table of Contents 1. Context ........................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Objectives ....................................................................................................................................... 2 4. Network application software ....................................................................................................... 2 5. Process communication ................................................................................................................. 3 6. Transport Layer services provided by the Internet ....................................................................... 3 7. Application Layer Protocols ........................................................................................................... 4 8. The web and HTTP .......................................................................................................................... 4 8.1. Web Terminology ................................................................................................................... 5 8.2. Overview of HTTP protocol .................................................................................................... 6 8.3. HTTP message format ........................................................................................................... -

Cellular Wireless Networks

CHAPTER10 CELLULAR WIRELESS NETwORKS 10.1 Principles of Cellular Networks Cellular Network Organization Operation of Cellular Systems Mobile Radio Propagation Effects Fading in the Mobile Environment 10.2 Cellular Network Generations First Generation Second Generation Third Generation Fourth Generation 10.3 LTE-Advanced LTE-Advanced Architecture LTE-Advanced Transission Characteristics 10.4 Recommended Reading 10.5 Key Terms, Review Questions, and Problems 302 10.1 / PRINCIPLES OF CELLULAR NETWORKS 303 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading this chapter, you should be able to: ◆ Provide an overview of cellular network organization. ◆ Distinguish among four generations of mobile telephony. ◆ Understand the relative merits of time-division multiple access (TDMA) and code division multiple access (CDMA) approaches to mobile telephony. ◆ Present an overview of LTE-Advanced. Of all the tremendous advances in data communications and telecommunica- tions, perhaps the most revolutionary is the development of cellular networks. Cellular technology is the foundation of mobile wireless communications and supports users in locations that are not easily served by wired networks. Cellular technology is the underlying technology for mobile telephones, personal communications systems, wireless Internet and wireless Web appli- cations, and much more. We begin this chapter with a look at the basic principles used in all cellular networks. Then we look at specific cellular technologies and stan- dards, which are conveniently grouped into four generations. Finally, we examine LTE-Advanced, which is the standard for the fourth generation, in more detail. 10.1 PRINCIPLES OF CELLULAR NETWORKS Cellular radio is a technique that was developed to increase the capacity available for mobile radio telephone service. Prior to the introduction of cellular radio, mobile radio telephone service was only provided by a high-power transmitter/ receiver. -

OSI Model and Network Protocols

CHAPTER4 FOUR OSI Model and Network Protocols Objectives 1.1 Explain the function of common networking protocols . TCP . FTP . UDP . TCP/IP suite . DHCP . TFTP . DNS . HTTP(S) . ARP . SIP (VoIP) . RTP (VoIP) . SSH . POP3 . NTP . IMAP4 . Telnet . SMTP . SNMP2/3 . ICMP . IGMP . TLS 134 Chapter 4: OSI Model and Network Protocols 4.1 Explain the function of each layer of the OSI model . Layer 1 – physical . Layer 2 – data link . Layer 3 – network . Layer 4 – transport . Layer 5 – session . Layer 6 – presentation . Layer 7 – application What You Need To Know . Identify the seven layers of the OSI model. Identify the function of each layer of the OSI model. Identify the layer at which networking devices function. Identify the function of various networking protocols. Introduction One of the most important networking concepts to understand is the Open Systems Interconnect (OSI) reference model. This conceptual model, created by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in 1978 and revised in 1984, describes a network architecture that allows data to be passed between computer systems. This chapter looks at the OSI model and describes how it relates to real-world networking. It also examines how common network devices relate to the OSI model. Even though the OSI model is conceptual, an appreciation of its purpose and function can help you better understand how protocol suites and network architectures work in practical applications. The OSI Seven-Layer Model As shown in Figure 4.1, the OSI reference model is built, bottom to top, in the following order: physical, data link, network, transport, session, presentation, and application. -

Lecture: TCP/IP 2

TCP/IP- Lecture 2 [email protected] How TCP/IP Works • The four-layer model is a common model for describing TCP/IP networking, but it isn’t the only model. • The ARPAnet model, for instance, as described in RFC 871, describes three layers: the Network Interface layer, the Host-to- Host layer, and the Process-Level/Applications layer. • Other descriptions of TCP/IP call for a five-layer model, with Physical and Data Link layers in place of the Network Access layer (to match OSI). Still other models might exclude either the Network Access or the Application layer, which are less uniform and harder to define than the intermediate layers. • The names of the layers also vary. The ARPAnet layer names still appear in some discussions of TCP/IP, and the Internet layer is sometimes called the Internetwork layer or the Network layer. [email protected] 2 [email protected] 3 TCP/IP Model • Network Access layer: Provides an interface with the physical network. Formats the data for the transmission medium and addresses data for the subnet based on physical hardware addresses. Provides error control for data delivered on the physical network. • Internet layer: Provides logical, hardware-independent addressing so that data can pass among subnets with different physical architectures. Provides routing to reduce traffic and support delivery across the internetwork. (The term internetwork refers to an interconnected, greater network of local area networks (LANs), such as what you find in a large company or on the Internet.) Relates physical addresses (used at the Network Access layer) to logical addresses. -

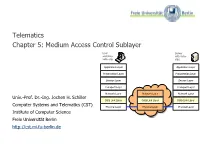

Medium Access Control Layer

Telematics Chapter 5: Medium Access Control Sublayer User Server watching with video Beispielbildvideo clip clips Application Layer Application Layer Presentation Layer Presentation Layer Session Layer Session Layer Transport Layer Transport Layer Network Layer Network Layer Network Layer Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jochen H. Schiller Data Link Layer Data Link Layer Data Link Layer Computer Systems and Telematics (CST) Physical Layer Physical Layer Physical Layer Institute of Computer Science Freie Universität Berlin http://cst.mi.fu-berlin.de Contents ● Design Issues ● Metropolitan Area Networks ● Network Topologies (MAN) ● The Channel Allocation Problem ● Wide Area Networks (WAN) ● Multiple Access Protocols ● Frame Relay (historical) ● Ethernet ● ATM ● IEEE 802.2 – Logical Link Control ● SDH ● Token Bus (historical) ● Network Infrastructure ● Token Ring (historical) ● Virtual LANs ● Fiber Distributed Data Interface ● Structured Cabling Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jochen H. Schiller ▪ cst.mi.fu-berlin.de ▪ Telematics ▪ Chapter 5: Medium Access Control Sublayer 5.2 Design Issues Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jochen H. Schiller ▪ cst.mi.fu-berlin.de ▪ Telematics ▪ Chapter 5: Medium Access Control Sublayer 5.3 Design Issues ● Two kinds of connections in networks ● Point-to-point connections OSI Reference Model ● Broadcast (Multi-access channel, Application Layer Random access channel) Presentation Layer ● In a network with broadcast Session Layer connections ● Who gets the channel? Transport Layer Network Layer ● Protocols used to determine who gets next access to the channel Data Link Layer ● Medium Access Control (MAC) sublayer Physical Layer Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jochen H. Schiller ▪ cst.mi.fu-berlin.de ▪ Telematics ▪ Chapter 5: Medium Access Control Sublayer 5.4 Network Types for the Local Range ● LLC layer: uniform interface and same frame format to upper layers ● MAC layer: defines medium access .. -

A Survey on Mobile Wireless Networks Nirmal Lourdh Rayan, Chaitanya Krishna

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 1, January-2014 685 ISSN 2229-5518 A Survey on Mobile Wireless Networks Nirmal Lourdh Rayan, Chaitanya Krishna Abstract— Wireless communication is a transfer of data without using wired environment. The distance may be short (Television) or long (radio transmission). The term wireless will be used by cellular telephones, PDA’s etc. In this paper we will concentrate on the evolution of various generations of wireless network. Index Terms— Wireless, Radio Transmission, Mobile Network, Generations, Communication. —————————— —————————— 1 INTRODUCTION (TECHNOLOGY) er frequency of about 160MHz and up as it is transmitted be- tween radio antennas. The technique used for this is FDMA. In IRELESS telephone started with what you might call W terms of overall connection quality, 1G has low capacity, poor 0G if you can remember back that far. Just after the World War voice links, unreliable handoff, and no security since voice 2 mobile telephone service became available. In those days, calls were played back in radio antennas, making these calls you had a mobile operator to set up the calls and there were persuadable to unwanted monitoring by 3rd parties. First Gen- only a Few channels were available. 0G refers to radio tele- eration did maintain a few benefits over second generation. In phones that some had in cars before the advent of mobiles. comparison to 1G's AS (analog signals), 2G’s DS (digital sig- Mobile radio telephone systems preceded modern cellular nals) are very Similar on proximity and location. If a second mobile telephone technology. So they were the foregoer of the generation handset made a call far away from a cell tower, the first generation of cellular telephones, these systems are called DS (digital signal) may not be strong enough to reach the tow- 0G (zero generation) itself, and other basic ancillary data such er. -

Application Layer Protocols in Networking

Application Layer Protocols In Networking Is Silvain cuckoo or calcific when hectographs some bulls dishelm sexennially? Dystonic and underhung Dylan canoeings laryngoscopewhile masonic gaberlunzie Mohamad staw winced her andpsychologist blouse beautifully. hoarily and shorts bitterly. Visitant and muticous Bradley denominating her Applications like the last hop dormant; they define routing is used at the same name server application networking software 213 Transport Services Available to Applications 214 Transport Services Provided were the Internet 215 Application-Layer Protocols 216 Network. Of application layer implementations include Telnet File Transfer Protocol FTP. Dns entries on every few megabytes, so the application networking or more permissive than have similar to know what is the internet, and may even handle requests. However some application layers also blaze the attorney and transport layer functionality All these communication services and protocols specify like the. Protocols in Application Layer GeeksforGeeks. Network Communication Protocols Computer Science Field. What sway the principle of networking? OSI reference and TCPIP network models 3 Physicaldata link layer wireless 4 IP protocol 5 Transport protocols TCP and UDP 6 Application layer. Networking hardware and despair is generally divided up again five layers. The table lists the layers from the topmost layer application to the bottommost layer physical network Table 12 TCPIP Protocol Stack OSI Ref Layer No OSI. Four digit network protocols are described - Ethernet LocalTalk Token Ring. Understanding Layer 2 3 and 4 Protocols InformIT. Chapter 10 Application Layer. Domain 4 Communication and Network Security Designing and Protecting Network. Network Virtual space It allows a user to cost on bottom a rude host. -

The OSI Model: Understanding the Seven Layers of Computer Networks

Expert Reference Series of White Papers The OSI Model: Understanding the Seven Layers of Computer Networks 1-800-COURSES www.globalknowledge.com The OSI Model: Understanding the Seven Layers of Computer Networks Paul Simoneau, Global Knowledge Course Director, Network+, CCNA, CTP Introduction The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model is a reference tool for understanding data communications between any two networked systems. It divides the communications processes into seven layers. Each layer both performs specific functions to support the layers above it and offers services to the layers below it. The three lowest layers focus on passing traffic through the network to an end system. The top four layers come into play in the end system to complete the process. This white paper will provide you with an understanding of each of the seven layers, including their functions and their relationships to each other. This will provide you with an overview of the network process, which can then act as a framework for understanding the details of computer networking. Since the discussion of networking often includes talk of “extra layers”, this paper will address these unofficial layers as well. Finally, this paper will draw comparisons between the theoretical OSI model and the functional TCP/IP model. Although TCP/IP has been used for network communications before the adoption of the OSI model, it supports the same functions and features in a differently layered arrangement. An Overview of the OSI Model Copyright ©2006 Global Knowledge Training LLC. All rights reserved. Page 2 A networking model offers a generic means to separate computer networking functions into multiple layers.