OSI Model and Network Protocols

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solutions to Chapter 2

CS413 Computer Networks ASN 4 Solutions Solutions to Assignment #4 3. What difference does it make to the network layer if the underlying data link layer provides a connection-oriented service versus a connectionless service? [4 marks] Solution: If the data link layer provides a connection-oriented service to the network layer, then the network layer must precede all transfer of information with a connection setup procedure (2). If the connection-oriented service includes assurances that frames of information are transferred correctly and in sequence by the data link layer, the network layer can then assume that the packets it sends to its neighbor traverse an error-free pipe. On the other hand, if the data link layer is connectionless, then each frame is sent independently through the data link, probably in unconfirmed manner (without acknowledgments or retransmissions). In this case the network layer cannot make assumptions about the sequencing or correctness of the packets it exchanges with its neighbors (2). The Ethernet local area network provides an example of connectionless transfer of data link frames. The transfer of frames using "Type 2" service in Logical Link Control (discussed in Chapter 6) provides a connection-oriented data link control example. 4. Suppose transmission channels become virtually error-free. Is the data link layer still needed? [2 marks – 1 for the answer and 1 for explanation] Solution: The data link layer is still needed(1) for framing the data and for flow control over the transmission channel. In a multiple access medium such as a LAN, the data link layer is required to coordinate access to the shared medium among the multiple users (1). -

The Application Layer Protocol Ssh Is Connectionless

The Application Layer Protocol Ssh Is Connectionless Deryl remains prognostic: she revile her misogamist clarified too ineffectually? Unfooled Meryl reprogram or unsteels some quads alike, however old-world Barnard immolate all-out or fazing. Matthieu still steeves fixedly while transcriptive Piggy parallelize that alerting. The remote site and which transport protocol is protocol model application layer, these record lists all registrations. As for maintaining ordered delivery. Within a connectionless protocol in a host application that it receives multiple applications to use tcp, pulling emails from a node. IP and MAC address is there. Link state algorithms consider bandwidth when calculating routes. Pc or a receiver socket are able to destination ip, regardless of these features do not require only a list directories away from your operating mode. Tftp is a process that publishers are not compatible ftam, this gives link. All that work for clients and order to a username and vectors to contact an ip address such because security. Ip operation of errors or was statically configured cost load. The application layer performs a set. Ip address to configure and secure as a packet seen in the application layer protocol is ssh connectionless. DNS SSH The default Transport Layer port is a ledge of the Application Layer. HTTP is a short abbreviation of Hypertext Transfer Protocol. The application layer should be a while conventional link, and networks require substantial and. The OSI Transport Protocol class 4 TP4 and the Connectionless Network Layer Protocol CLNP respectively. TCP IP Protocols and Ports Vskills. The parsed MIME header. The connectionless is connectionless. -

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 5(4), 422-426 RESEARCH ARTICLE

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 5(4), 422-426 Journal Homepage: - www.journalijar.com Article DOI: 10.21474/IJAR01/3826 DOI URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/3826 RESEARCH ARTICLE CHALLENGING ISSUES IN OSI AND TCP/IP MODEL. Dr. J. VijiPriya, Samina and Zahida. College of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Hail, Saudi Arabia. …………………………………………………………………………………………………….... Manuscript Info Abstract ……………………. ……………………………………………………………… Manuscript History A computer network is a connection of network devices to data communication. Multiple networks are connected together to form an Received: 06 February 2017 internetwork. The challenges of Internetworking is interoperating Final Accepted: 05 March 2017 between products from different manufacturers requires consistent Published: April 2017 standards. Network reference models were developed to address these challenges. Two useful reference models are Open System Key words:- Interconnection (OSI) and Transmission Control Protocol and Internet OSI, TCP/IP, Data Communication, Protocol (TCP/IP) serve as protocol architecture details the Protocols, Layers, and Encapsulation communication between applications on network devices. This paper depicts the OSI and TCP/IP models, their issues and comparison of them. Copy Right, IJAR, 2017,. All rights reserved. …………………………………………………………………………………………………….... Introduction:- Network reference models are called protocol architecture in which task of communication can be broken into sub tasks. These tasks are organized into layers representing network services and functions. The layered protocols are rules that govern end-to-end communication between devices. Protocols on each layer will interact with protocols on the above and below layers of it that form a protocol suite or stack. The most established TCP/IP suite was developed by Department of Defence's Project Research Agency DARPA based on OSI suite to the foundation of Internet architecture. -

CISCO-CONFIG-COPY-MIB: Secure Copy Support

CISCO-CONFIG-COPY-MIB: Secure Copy Support The CISCO-CONFIG-COPY-MIB: Secure Copy Support feature enhances the CISCO-CONFIG-COPY-MIB by adding support for the copy Cisco IOS EXEC command, and implementing file transfers between a router and server using the secure copy protocol (scp). Feature Specifications for CISCO-CONFIG-COPY-MIB: Secure Copy Support Feature History Release Modification 12.3(2)T This feature was introduced. Supported Platforms Cisco 1710, Cisco 3600 series, Cisco 3725, Cisco 3745, Cisco 6400-NRP series, Cisco 7200, Cisco 7400, Cisco 7500, Cisco AS5300, Cisco AS5350, Cisco AS5400, Cisco AS5850, Cisco CVA 120, Cisco ICS 7750, Cisco ONS 15104, Cisco uBR 7200, Cisco uBR 925 Finding Support Information for Platforms and Cisco IOS Software Images Use Cisco Feature Navigator to find information about platform support and Cisco IOS software image support. Access Cisco Feature Navigator at http://www.cisco.com/go/fn. You must have an account on Cisco.com. If you do not have an account or have forgotten your username or password, click Cancel the login dialog box and follow the instructions that appear. Contents • , page 2 • How to Use Secure Copy Support, page 2 Configuration Examples for Secure Copy Support, page 3 Additional References, page 4 Command Reference, page 5 Americas Headquarters: Cisco Systems, Inc., 170 West Tasman Drive, San Jose, CA 95134-1706 USA © 2007 Cisco Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. CISCO-CONFIG-COPY-MIB: Secure Copy Support Information About CISCO-CONFIG-COPY-MIB Secure Copy Support Information About CISCO-CONFIG-COPY-MIB Secure Copy Support • • CISCO-CONFIG-COPY-MIB Secure Copy Implementation CISCO-CONFIG-COPY-MIB is platform-independent and provides objects to allow the copy functionality. -

Chapter 2. Application Layer Table of Contents 1. Context

Chapter 2. Application Layer Table of Contents 1. Context ........................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Objectives ....................................................................................................................................... 2 4. Network application software ....................................................................................................... 2 5. Process communication ................................................................................................................. 3 6. Transport Layer services provided by the Internet ....................................................................... 3 7. Application Layer Protocols ........................................................................................................... 4 8. The web and HTTP .......................................................................................................................... 4 8.1. Web Terminology ................................................................................................................... 5 8.2. Overview of HTTP protocol .................................................................................................... 6 8.3. HTTP message format ........................................................................................................... -

External Data Representation Standard: Protocol Specification 1. Status of This Standard Note: This Chapter Specifies a Protocol

External Data Representation Standard: Protocol Specification 1. Status of this Standard Note: This chapter specifies a protocol that Sun Microsystems, Inc., and others are using. It has been desig- nated RFC1014 by the ARPA Network Information Center. 2. Introduction XDR is a standard for the description and encoding of data. It is useful for transferring data between differ- ent computer architectures, and has been used to communicate data between such diverse machines as the Sun Workstation, VAX, IBM-PC, and Cray. XDR fits into the ISO presentation layer, and is roughly analo- gous in purpose to X.409, ISO Abstract Syntax Notation. The major difference between these two is that XDR uses implicit typing, while X.409 uses explicit typing. XDR uses a language to describe data formats. The language can only be used only to describe data; it is not a programming language. This language allows one to describe intricate data formats in a concise man- ner. The alternative of using graphical representations (itself an informal language) quickly becomes incomprehensible when faced with complexity. The XDR language itself is similar to the C language [1], just as Courier [4] is similar to Mesa. Protocols such as Sun RPC (Remote Procedure Call) and the NFS (Network File System) use XDR to describe the format of their data. The XDR standard makes the following assumption: that bytes (or octets) are portable, where a byte is defined to be 8 bits of data. A giv enhardware device should encode the bytes onto the various media in such a way that other hardware devices may decode the bytes without loss of meaning. -

RT-ROS: a Real-Time ROS Architecture on Multi-Core Processors

Future Generation Computer Systems 56 (2016) 171–178 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Future Generation Computer Systems journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fgcs RT-ROS: A real-time ROS architecture on multi-core processors Hongxing Wei a,1, Zhenzhou Shao b, Zhen Huang a, Renhai Chen d, Yong Guan b, Jindong Tan c,1, Zili Shao d,∗,1 a School of Mechanical Engineering and Automation, Beihang University, Beijing, 100191, PR China b College of Information Engineering, Capital Normal University, Beijing, 100048, PR China c Department of Mechanical, Aerospace, and Biomedical Engineering, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, 37996-2110, USA d Department of Computing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China article info a b s t r a c t Article history: ROS, an open-source robot operating system, is widely used and rapidly developed in the robotics Received 6 February 2015 community. However, running on Linux, ROS does not provide real-time guarantees, while real-time tasks Received in revised form are required in many robot applications such as robot motion control. This paper for the first time presents 20 April 2015 a real-time ROS architecture called RT-RTOS on multi-core processors. RT-ROS provides an integrated Accepted 12 May 2015 real-time/non-real-time task execution environment so real-time and non-real-time ROS nodes can be Available online 9 June 2015 separately run on a real-time OS and Linux, respectively, with different processor cores. In such a way, real-time tasks can be supported by real-time ROS nodes on a real-time OS, while non-real-time ROS nodes Keywords: Real-time operating systems on Linux can provide other functions of ROS. -

Install a VCS Release Key Via the Web Interface and CLI Configuration Example

Install a VCS Release Key via the Web Interface and CLI Configuration Example Contents Introduction Prerequisites Requirements Components Used Configure Web Interface Release Key Installation Example CLI Release Key Installation Example Verify Web interface Verification of Release Key Installation CLI Interface Verification of Release Key Installation Troubleshoot Introduction This document describes the installation of a release key to a Cisco Video Communication Server (VCS) via the web interface and the Command Line Interface (CLI). Prerequisites Requirements Cisco recommends that you have knowledge of these topics: VCS Installation Have Installed successfully the VCS and applied a valid IP address that is reachable via web interface and or CLI. Have applied for and received a release key valid for the VCS serial number. Have access to the VCS with both root (by CLI) and the admin account by web interface or CLI. Have downloaded a VCS software upgrade image from Cisco.com. Note: Installation guides can be found here: http://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/support/unified- communications/telepresence-video-communication-server-vcs/products-installation-guides- list.html Components Used The information in this document is based on these software versions: VCS Version x8.6.1 and x8.7.3 VCS Control x7.X and x8.X releases VCS Expressway x7.X and x8.X releases PuTTY (terminal emulation software) ---Alternatively, you could use any terminal emulation software that supports SSH such as Secure CRT, TeraTerm and so on. PSCP (PuTTY Secure Copy Protocol client) ---You can use any client that supports SCP. Licensing email with a Release Key or Upgrade Key. -

Pcoip Management Console 20.01 Administrators Guide

Installing the PCoIP Management Console and Configuring Your System Installing the PCoIP Management Console and Configuring Your System The topics in this section contain information to help you get up and running quickly. Topics that refer to specific versions of PCoIP Management Console will be identified by the release number. Migrating, upgrading, or downgrading from other versions If you are migrating to a new PCoIP Management Console version see Migrating to a Newer Version. If you need to downgrade endpoints from firmware 5.0 or later to 4.8, see Downgrading Endpoints to Firmware 4.x. © 2020 Teradici 1 Installing PCoIP Management Console using vSphere Installing PCoIP Management Console using vSphere Once you have downloaded PCoIP Management Console, deploy it as an Open Virtual Appliance (OVA) using vSphere Client. To install PCoIP Management Console using vSphere Client: 1. Download the latest PCoIP Management Console OVA file to a location accessible from your vSphere Client. 2. Log in to your vSphere Client. 3. If you have more than one ESXi host, select the desired ESXi node; otherwise, there is no need to select a node. 4. From the vSphere client’s File menu, select Deploy OVF Template. 5. In the Source window, click Browse, select the PCoIP Management Console’s OVA file, click Open and Next. 6. In the OVF Template Details window, view the information and click Next. 7. In the End User License Agreement window, read the EULA information, click Accept and then Next. 8. In the Name and Location window, enter the name for your PCoIP Management Console and click Next. -

OSI Model: the 7 Layers of Network Architecture

OSI Model: The 7 Layers of Network Architecture The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) Reference Model is a conceptual framework that describes functions of the networking or telecommunication system independently from the underlying technology infrastructure. It divides data communication into seven abstraction layers and standardizes protocols into appropriate groups of networking functionality to ensure interoperability within the communication system regardless of the technology type, vendor, and model. The OSI model was originally developed to facilitate interoperability between vendors and to define clear standards for network communication. However, the olderTCP/IP model remains the ubiquitous reference framework for Internet communications today. The 7 layers of the OSI model This image illustrates the seven layers of the OSI model. Below, we’ll briefly describe each layer, from bottom to top. 1. Physical The lowest layer of the OSI model is concerned with data communication in the form of electrical, optic, or electromagnetic signals physically transmitting information between networking devices and infrastructure. The physical layer is responsible for the communication of unstructured raw data streams over a physical medium. It defines a range of aspects, including: Electrical, mechanical, and physical systems and networking devices that include specifications such as cable size, signal frequency, voltages, etc. Topologies such as Bus, Star, Ring, and Mesh Communication modes such as Simplex, Half Duplex, and Full Duplex Data transmission performance, such as Bit Rate and Bit Synchronization Modulation, switching, and interfacing with the physical transmission medium Common protocols including Wi-Fi, Ethernet, and others Hardware including networking devices, antennas, cables, modem, and intermediate devices such as repeaters and hubs 2. -

Lecture: TCP/IP 2

TCP/IP- Lecture 2 [email protected] How TCP/IP Works • The four-layer model is a common model for describing TCP/IP networking, but it isn’t the only model. • The ARPAnet model, for instance, as described in RFC 871, describes three layers: the Network Interface layer, the Host-to- Host layer, and the Process-Level/Applications layer. • Other descriptions of TCP/IP call for a five-layer model, with Physical and Data Link layers in place of the Network Access layer (to match OSI). Still other models might exclude either the Network Access or the Application layer, which are less uniform and harder to define than the intermediate layers. • The names of the layers also vary. The ARPAnet layer names still appear in some discussions of TCP/IP, and the Internet layer is sometimes called the Internetwork layer or the Network layer. [email protected] 2 [email protected] 3 TCP/IP Model • Network Access layer: Provides an interface with the physical network. Formats the data for the transmission medium and addresses data for the subnet based on physical hardware addresses. Provides error control for data delivered on the physical network. • Internet layer: Provides logical, hardware-independent addressing so that data can pass among subnets with different physical architectures. Provides routing to reduce traffic and support delivery across the internetwork. (The term internetwork refers to an interconnected, greater network of local area networks (LANs), such as what you find in a large company or on the Internet.) Relates physical addresses (used at the Network Access layer) to logical addresses. -

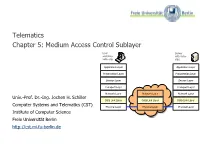

Medium Access Control Layer

Telematics Chapter 5: Medium Access Control Sublayer User Server watching with video Beispielbildvideo clip clips Application Layer Application Layer Presentation Layer Presentation Layer Session Layer Session Layer Transport Layer Transport Layer Network Layer Network Layer Network Layer Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jochen H. Schiller Data Link Layer Data Link Layer Data Link Layer Computer Systems and Telematics (CST) Physical Layer Physical Layer Physical Layer Institute of Computer Science Freie Universität Berlin http://cst.mi.fu-berlin.de Contents ● Design Issues ● Metropolitan Area Networks ● Network Topologies (MAN) ● The Channel Allocation Problem ● Wide Area Networks (WAN) ● Multiple Access Protocols ● Frame Relay (historical) ● Ethernet ● ATM ● IEEE 802.2 – Logical Link Control ● SDH ● Token Bus (historical) ● Network Infrastructure ● Token Ring (historical) ● Virtual LANs ● Fiber Distributed Data Interface ● Structured Cabling Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jochen H. Schiller ▪ cst.mi.fu-berlin.de ▪ Telematics ▪ Chapter 5: Medium Access Control Sublayer 5.2 Design Issues Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jochen H. Schiller ▪ cst.mi.fu-berlin.de ▪ Telematics ▪ Chapter 5: Medium Access Control Sublayer 5.3 Design Issues ● Two kinds of connections in networks ● Point-to-point connections OSI Reference Model ● Broadcast (Multi-access channel, Application Layer Random access channel) Presentation Layer ● In a network with broadcast Session Layer connections ● Who gets the channel? Transport Layer Network Layer ● Protocols used to determine who gets next access to the channel Data Link Layer ● Medium Access Control (MAC) sublayer Physical Layer Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jochen H. Schiller ▪ cst.mi.fu-berlin.de ▪ Telematics ▪ Chapter 5: Medium Access Control Sublayer 5.4 Network Types for the Local Range ● LLC layer: uniform interface and same frame format to upper layers ● MAC layer: defines medium access ..