The Mansion of Thought – Making Knowledge Visible in Three Dimensions, East and West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ferrara Di Ferrara

PROVINCIA COMUNE DI FERRARA DI FERRARA Visit Ferraraand its province United Nations Ferrara, City of Educational, Scientific and the Renaissance Cultural Organization and its Po Delta Parco Urbano G. Bassani Via R. Bacchelli A short history 2 Viale Orlando Furioso Living the city 3 A year of events CIMITERO The bicycle, queen of the roads DELLA CERTOSA Shopping and markets Cuisine Via Arianuova Viale Po Corso Ercole I d’Este ITINERARIES IN TOWN 6 CIMITERO EBRAICO THE MEDIAEVAL Parco Corso Porta Po CENTRE Via Ariosto Massari Piazzale C.so B. Rossetti Via Borso Stazione Via d.Corso Vigne Porta Mare ITINERARIES IN TOWN 20 Viale Cavour THE RENAISSANCE ADDITION Corso Ercole I d’Este Via Garibaldi ITINERARIES IN TOWN 32 RENAISSANCE Corso Giovecca RESIDENCES Piazza AND CHURCHES Trento e Trieste V. Mazzini ITINERARIES IN TOWN 40 Parco Darsena di San Paolo Pareschi WHERE THE RIVER Piazza Travaglio ONCE FLOWED Punta della ITINERARIES IN TOWN 46 Giovecca THE WALLS Via Cammello Po di Volano Via XX Settembre Via Bologna Porta VISIT THE PROVINCE 50 San Pietro Useful information 69 Chiesa di San Giorgio READER’S GUIDE Route indications Along with the Pedestrian Roadsigns sited in the Historic Centre, this booklet will guide the visitor through the most important areas of the The “MUSEO DI QUALITÀ“ city. is recognised by the Regional Emilia-Romagna The five themed routes are identified with different colour schemes. “Istituto per i Beni Artistici Culturali e Naturali” Please, check the opening hours and temporary closings on the The starting point for all these routes is the Tourist Information official Museums and Monuments schedule distributed by Office at the Estense Castle. -

Ferraraand Its Province

Visit and its province Ferrara EN Provincia Comune di Ferrara di Ferrara A SHORT HISTORY INDEX The origins of Ferrara are wrapped in mystery. Its name is 2 ITINERARIES IN TOWN mentioned for the first time in a document dating to 753 A.D., 2 The Renaissance addition issued by the Longobard king Desiderius. In the earliest centu- 14 The Mediaeval centre ries of its life the city had several different rulers, later it gained 28 Renaissance residences and churches enough freedom to become an independent Commune. After 36 Where the river once flowed some years of fierce internal struggles between the Guelph 42 The Walls and the Ghibelline factions, the Este family took control of the city. 46 LIVE THE CITY 46 Events all year round The great cultural season began in 1391, when the University 47 Bicycles was founded, and afterwards culture and magnificence grew 48 Shopping and markets unceasingly. Artists like Leon Battista Alberti, Pisanello, Piero 49 Cuisine della Francesca, Rogier van der Weyden and Tiziano came to Ferrara and the local pictorial school, called “Officina Ferra- 50 VISIT THE PROVINCE rese” produced the masterpieces of Cosmè Tura, Ercole de’ Roberti and Francesco del Cossa. The best musicians of the 69 USEFUL INFORMATION time worked for the Dukes of Ferrara, who also inspired the immortal poetry of Boiardo, Ariosto and Tasso. Niccolò III, the diplomat, Leonello, the intellectual, Borso, the Download the podguides magnificent, Ercole I, the constructor, and Alfonso I, the sol- and discover Ferrara and its province: dier: these are the names of some famous lords of Ferrara, www.ferrarainfo.com/html/audioguide/indexEN.htm still recalled together with those of the family’s princesses: the unlucky Parisina Malatesta, the wise Eleonora d’Aragona, the beautiful and slandered Lucrezia Borgia, Renée of France, the READER’S GUIDE intellectual follower of Calvinism. -

2018 Mosaics of Northern Italy Tour 14 Days Venice, Spilimbergo, Ravenna 14 – 28 May 2018

2018 MOSAICS OF NORTHERN ITALY TOUR 14 DAYS VENICE, SPILIMBERGO, RAVENNA 14 – 28 MAY 2018 Orsoni colour library, Venice with Helen Bodycomb in association with In Giro Tours, La Scuola di Mosaicisti del Friuli and Koko Mosaico THE TOUR BEGINS IN VENICE AND CONCLUDES IN RAVENNA, FOR A MAXIMUM OF 10 PEOPLE Following the highly successful inaugural Mosaics of northern Italy Tour in 2017, this unique boutique-sized tour will be held again in 2018. Designed for the further education and enjoyment of practicing amateur and professional mosaicists, we focus on prominent mosaic sites dating from the Roman Era, through Paleo-Christian to the contemporary, together with two short practical mosaic courses conducted by two of Italy’s leading Mosaic Maestri – Carolina Zanelli (La Scuola di Mosaicisti del Friuli, Spilimbergo) and Arianna Gallo (Koko Mosaico, Ravenna). 4 days / 4 nights in Venice 14 – 18 May with Tour Leaders Ingrid Gaiotto (In Giro Tours) and Helen Bodycomb Venice highlights include a private water tour of Venice with local guides, Basilica di San Marco, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Islands of Murano and Burano, Torcello, and the Orsoni glass smalti factory. With centrally located accommodation in one of Venice’s finest upper mid-range boutique hotels and a scrumptious array of true Venetian culinary experiences, Venice – La Serenissima - provides a thrilling and inspirational start to this 14-day Tour. 4 days / 4 nights Spilimbergo 18 – 22 May with Tour Leaders/Mosaic Instructors Helen Bodycomb and Carolina Zanelli (Scuola di Mosaicisti del Friuli) Spilimbergo is a small, medieval walled town in Friuli-Venezia-Giulia that hosts the world’s leading contemporary mosaic art school, La Scuola di Mosaicisti del Friuli. -

H the OFFICIAL JOURNAL of the ITALY & COLONIES STUDY CIRCLE F H VOLUME XLVI- No. 2 (Whole Number 184) Spring 2020 F Cove

Winner of 3 Gold Medals at A.P.S. STAMPSHOW 2015, 2016 and 2018 h THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE ITALY & COLONIES STUDY CIRCLE f PAPAL STATES 3 CENT - page 55 - 61 THE FORGOTTEN MEZZANA page - 62 - 75 h VOLUME XLVI- No. 2 (Whole Number 184) Spring 2020 f cover price £6 54 FIL-ITALIA ,Volume XLVI, no. 2 Spring 2020 Volume XLVI, No. 2 Whole number 184 Spring 2020 One of my editorials during the 35 hurricane seasons I lived through was titled “Expect the Unexpected” and a similar one 54 Papal States - 3 cent was titled “Overprepared is better than unprepared”. I need not elaborate, you know what I am aiming at during our Covid-19 Roberto Quondamatteo trying times. The impact of the emergency has also affected the stamp 62 The forgotten Mezzana world, suffice to mention the postponement of London 2020. Francesco Giuliani Yet, for many of us, philately and postal history are proving therapeutic during the lockdown and restrictions caused by 76 Fiume’s Hand-overprints the pandemic. Our brain activity does not waste time to feed depression and hypochondria; instead, we should be fully Ivan Martinas & Nenad Rogina absorbed in our puzzles about overprints, postal tariffs, reprints, 90 Aeolian Isles Natante Post Offices “return to sender” covers (speaking of which we should return Covid-19 to the sender). We watch less television and read fewer Alan Becker newspapers; we happily soak stamps, measure perforations, look for a sideways watermark, and the location of a certain Field Post 92 Fiume Addenda Office. We ought to thank: Rowland Hill for inventing this piece Clive Griffiths of gummed paper; the Tassis dynasty of postal entrepreneurs who served most of Europe and modernised the service; thanks 93 A curious airmail item go to the wise men who instead of throwing away letters and covers they archived them, thus perpetuating the enjoyment Richard Harlow of postal historians who delve into postal minutiae of the past, 94 An 1801 puzzle thereby reconstructing a whole epoch of hitherto neglected, yet important details. -

A Living Past: the Historical Environment of the Middle Ages

A living past: The historical environment of the Middle Ages The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Constable, Giles. 1990. A living past: The historical environment of the Middle Ages. Harvard Library Bulletin 1 (3), Fall 1990: 49-70. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42661216 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 49 A Living Past: The Historical Environment of the Middle Ages Giles Constable his paper looks at some questions that arose in the course of preparing an article T on the attitude towards time and the past in the twelfth century. 1 I particularly noticed that the environment created by art, architecture, and ceremony fostered a closeness, and at times an identity, with history. People lived the past in a very real sense, and the past, living in them, was constantly recreated in a way that made it part of everyday life. Scholars tend to rely so heavily on verbal sources that they underestimate the influence of the senses in developing an awareness of history. Sight, smell, hearing, and touch were all enlisted in the task of reconstructing the past. Even speech was a dramatic performance, and the actions that accompanied many rites and ceremonies helped to bring past people and events into the present, giving meaning to history and linking it to the future. -

Experiencing the Chapterhouse in the Benedictine Abbey at Pomposa

Experiencing the Chapterhouse in the Benedictine Abbey at Pomposa The Benedictine Abbey at Pomposa is located in the Po valley east of Ferrara, on the isolated and marshy coastline of the Adriatic Sea.1 Established in the eighth century, it was an active and vibrant complex for almost a thousand years, until repeated outbreaks of malaria forced the monks to abandon it in the seventeenth century (Salmi 14). Notable monks associated with the abbey in its eleventh-century heyday include the music theorist Guido d’Arezzo (c. 991-after 1033), the pious abbot St. Guido degli Strambiati (c. 970-1046), and the writer and reformer St. Peter Damian (1007-72) (Caselli 10-15). The poet Dante called on the abbey, as an emissary for the da Polenta court in Ravenna, shortly before his death in 1321 (Caselli 16). His visit coincided with a great period of renewal under the administration of the abbot Enrico (1302-20), during which fresco cycles in the Chapterhouse and Refectory were executed by artists of the Riminese school. This investigation of the Chapterhouse (Fig. 1-3) reveals that the Benedictines at the Pomposa Abbey, just prior to 1320, created an environment in which illusionistic painting techniques are coupled with references to rhetorical dialogue and theatrical conventions, to allow for the performative and interactive engagement of those who use the space and those depicted on the surrounding walls.2 FLEMING Fig. 1 Pomposa Chapterhous, interior view facing crucifixion (photo: author) Fig. 2 Pomposa Chapterhouse, interior view towards left wall (photo: author) 140 EXPERIENCING THE CHAPTERHOUSE AT POMPOSA Fig. -

Emilia Romagna

PROJECT ITINERARI PER SCOPRIRE LA WELLNESS VALLEY PAG.04 WELLNESS VALLEY DISCOVERY TOURS ENTDECKEN SIE DIE ZAHLREICHENDEN REISEWEGE DES WELLNESS VALLEYS TOOLS LA WELLNESS VALLEY IN TASCA CON PRATICHE GUIDE PAG.08 THE WELLNESS VALLEY IN YOUR POCKET WITH PRACTICAL GUIDES DER WELLNESS VALLEY MIT PRAKTISCHEM LEITFADEN EINFACH BEI DER HAND ROUTE ITINERARI PER ESCURSIONISTI E AMANTI DELLE CAMMINATE PAG.12 ROUTES FOR HIKERS AND WALKERS REISEWEGE FÜR WANDERER UND SPAZIERGÄNGER ROUTE PERCORSI DA VIVERE SU DUE ROUTE PAG.40 TWO-WHEELED TRAILS ERLEBEN SIE DEN VALLEY AUF ZWEI RÄDERN PROJECT ITINERARI PER SCOPRIRE LA WELLNESS VALLEY Vivere all’aria aperta in Romagna è uno stile di vita. Più di 2.000 km, fra piste ciclabili, percorsi stradali e tracciati sterrati la attraversano, rappresentando una grande opportunità per un territorio da sempre votato alla vita attiva e al benessere. Trascorrere una vacanza in movimento in mezzo alla natura signifi ca assaporare la qualità della vita che qui si respira. Al cicloamatore come all’appassionato di trekking e all’amante di escursioni e passeggiate, la Wellness Valley offre decine di opportunità, dal mare all’Appennino, per scoprire le sue radici più autentiche, le eccellenze enogastronomiche, la sua arte e cultura. Una terra unica, dove la spontanea ospitalità delle persone rende tutto più speciale! WELLNESS VALLEY ENTDECKEN SIE DIE DISCOVERY TOURS ZAHLREICHENDEN REISEWEGE DES Living outdoors in Romagna is a way of life. WELLNESS VALLEYS More than 2000 kilometres of cycle lanes, road routes and dirt tracks go through the region, Hier in Romagna ist das Leben im Freien eine Weise representing a big opportunity for a land that des Seins. -

THE LAST JUDGMENT in CHRISTIAN ICONOGRAPHY Alison Morgan Public Lecture Given in the University of Cambridge, 1987

THE LAST JUDGMENT IN CHRISTIAN ICONOGRAPHY Alison Morgan Public lecture given in the University of Cambridge, 1987 I gave this lecture many years ago as part of my doctoral research into the iconography of Dante’s Divine Comedy, using slides to illustrate the subject matter. Thanks to digital technology it is now possible to create an illustrated version. The text remains in the original lecture form – in other words full references are not given. Illustrations are in the public domain, and acknowledged where appropriate; some are my own photographs. If I were giving this lecture today I would want to include material from eastern Europe which was not readily accessible at the time. But I hope this may serve by way of an introduction to the subject. Alison Morgan, September 2019 www.alisonmorgan.co.uk A. INTRODUCTION 1. Christian belief concerning the Last Judgment The subject of this lecture is the representation of the Last Judgment in Christian iconography. I would like therefore to begin by reminding you what it is that Christians believe about the Last Judgment. Throughout the centuries people have turned to the Gospel of Matthew as their main authority concerning the end of time. In chapter 25 Matthew records these words spoken by Jesus on the Mount of Olives: ‘When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left. -

Download Free at ISBN 978‑1‑909646‑72‑8 (PDF Edition) DOI: 10.14296/917.9781909646728

Ravenna its role in earlier medieval change and exchange Ravenna its role in earlier medieval change and exchange Edited by Judith Herrin and Jinty Nelson LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2016 (ISBN 978‑1‑909646‑14‑8) This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution‑ NonCommercial‑NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY‑ NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities‑digital‑library.org ISBN 978‑1‑909646‑72‑8 (PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/917.9781909646728 iv Contents Acknowledgements vii List of contributors ix List of illustrations xiii Abbreviations xvii Introduction 1 Judith Herrin and Jinty Nelson 1. A tale of two cities: Rome and Ravenna under Gothic rule 15 Peter Heather 2. Episcopal commemoration in late fifth‑century Ravenna 39 Deborah M. Deliyannis 3. Production, promotion and reception: the visual culture of Ravenna between late antiquity and the middle ages 53 Maria Cristina Carile 4. Ravenna in the sixth century: the archaeology of change 87 Carola Jäggi 5. The circulation of marble in the Adriatic Sea at the time of Justinian 111 Yuri A. Marano 6. Social instability and economic decline of the Ostrogothic community in the aftermath of the imperial victory: the papyri evidence 133 Salvatore Cosentino 7. A striking evolution: the mint of Ravenna during the early middle ages 151 Vivien Prigent 8. Roman law in Ravenna 163 Simon Corcoran 9. -

Swan Hellenic Swan Hellenic Swan Hellenic SWAN Summer 2016

ISSUED DECEMBER 2015 March – October 2017 To book or request a brochure Summer 2017 01858 414 001 visit www.swanhellenic.com or contact your local travel agent Swan Hellenic Swan Hellenic Swan Hellenic SWAN Summer 2016. Worldwide small Winter 2016/17. Classic cultural cruising River Cruises ship discovery cruises with inclusive exploring the beautiful waters of the Our award-winning river cruise shore excursions and renowned Mediterranean and featuring extended programme features journeys Guest Speaker programmes stays in incredible destinations from along the Rhône, the Saône and Istanbul to Seville and Sao Vicente the Rhine HELLENIC Classic Cultural Cruising Brochures from our sister companies SWAN HELLENIC DISCOVERY CRUISES SWAN DEPARTURES 2016/17 DEPARTURES 2016/17 WE'RE THE SINGLE TRAVELLER SPECIALIST TRAVELSPHERE AWARD-WINNING AWARD-WINNING ESCORTED TOURS - EUROPE ESCORTED HOLIDAYS 2016/17 ESCORTED TOURS WITH SO MUCH WITH SO MUCH USA, CANADA & INCLUDED INCLUDED WORLDWIDE HOLIDAYS EUROPE WITH THE EXPERTS HOLIDAYS FROM WITH THE EXPERTS FROM £949 £379 EUROPE & WORLDWIDE HOLIDAYS ESCORTED HOLIDAYS 2016 WITH NO SINGLE SUPPLEMENT DECEMBER2015 travelsphere.co.uk INDIA - FAR EAST - SOUTH AMERICA - AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND & MORE ITALY - CROATIA - GREECE - SPAIN - PORTUGAL - FRANCE - AUSTRIA & MORE Travelsphere Escorted Travelsphere Escorted Just You holidays Voyages of Discovery Hebridean Hebridean Holiday Collection Holiday Collection - for single travellers Incorporating the Island Cruises River Cruises - USA, Canada & Europe Award winning -

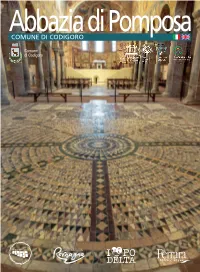

Abbazia Di Pomposa COMUNE DI CODIGORO

Abbazia di Pomposa COMUNE DI CODIGORO Comune di Codigoro Opuscolo Abbazia di Pomposa.indd 1 23/02/20 12:27 Cronologia essenziale Essential chronology • Secc. VI-VII / 6th-7th centuries Strambiati. Insediamento della prima comunità Guido degli Strambiati of Ravenna ap- monastica nell’Insula Pomposiana. pointed Abbot. First monastic settlement on the insula pomposiana. • 1022 Pomposa è dichiarata autonoma. • 874 Pomposa is given self-governing rights. Prima menzione scritta di Pomposa. First written record of Pomposa. • 7/5/1026 Riconsacrazione della Chiesa. Am- • Secc. VIII-IX / 8th-9th centuries pliamento del convento. Tracce archeologiche di una primiti- The church is reconsecrated and the va chiesetta. monastery extended. Remains of a primitive chapel. • 1026 • 962-999 Esecuzione dell’atrio della chiesa ad Pomposa è donata dagli Ottoni di opera di magister Mazulo. Sassonia al vescovo di Comacchio, The entrance gallery of the church is quindi al monastero di S. Salvatore di built by Master Mazulo. Pavia, infine ai vescovi di Ravenna. Period of donations by the Otto Em- • 1040-1042 perors of Saxony. Pomposa is granted San Pier Damiani a Pomposa. to the Bishop of Comacchio, then to St. Pier Damiani resides in Pomposa. the S. Salvatore Monastery of Pavia and finally to the Bishops of Ravenna. • 1046 Morte dell’abate Guido: l’imperatore • 1001 Enrico III porta le spoglie a Spira in L’imperatore Ottone III concede il ti- Germania. tolo di Regalis Abbatia. Death of Abbot Guido. Emperor Henry Emperor Otto III grants it the title of III removes the mortal remains to Spira Royal Abbey (Regalis Abbatia). in Germany. -

Rimini-Spirito-EN.Pdf

Main places of interest and itineraries Where to find us Trento Bellaria Milano Venezia Igea Marina Torino Bologna Oslo Helsinki Genova Ravenna Rimini Stoccolma Mosca Firenze Ancona Dublino Perugia Santarcangelo Londra Amsterdam Varsavia di Romagna Bruxelles Kijev Roma Rimini Berlino Praga Poggio Berni Vienna Bari Parigi Monaco Napoli Budapest Milano Torriana Bucarest Verucchio Rimini Madrid Cagliari Riccione Roma Catanzaro Ankara Talamello Coriano Atene Palermo Repubblica Algeri Misano Adriatico Tunisi Novafeltria di San Marino Sant’Agata Feltria San Leo Montescudo Maiolo Monte Colombo Cattolica San Clemente fiume Conca Gemmano Morciano San Giovanni Pennabilli di Romagna in Marignano Casteldelci AR Montefiore Conca Piacenza Saludecio Montegridolfo Mondaino Ferrara Parma fiume Marecchia Reggio Emilia Modena Coriano - Sanctuary of Santa Maria della Misericordia (Santa Chiara) - Convent and Institute of the Maestre Pie - Small temple of Sant’Antonio Bologna Gemmano Saludecio Ravenna - Sanctuary of the Madonna di Carbognano - Church of San Girolamo Maiolo - Sanctuary of the Madonna del Monte - Church of Santa Maria d’Antico - Sanctuary and Museum of the Blessed Amato Misano Adriatico San Giovanni in Marignano Forlì - Church of the Immacolata Concezione - Church of Santa Lucia Cesena Mondaino - Church of San Pietro - Convent of the Clarisse San Leo Rimini Montefiore Conca - Cathedral - Sanctuary of the Madonna of Bonora - Parish church of Santa Maria Assunta - Church of San Paolo - Monastery of Sant’Igne San Marino - Church of the Ospedale