Music and the Underground Railroad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can She Trust You Is a Live, Interactive

Recommended Grades: 3-8 Recommended Length: 40-50 minutes Presentation Overview: Can She Trust You is a live, interactive, distance learning program through which students will interact with the residents of the 1860 Ohio Village to help Rowena, a runaway slave who is searching for assistance along her way to freedom. Students will learn about each village resident, ask questions, and listen for clues. Their objective is to discover which resident is the Underground Railroad conductor and who Rowena can trust. Presentation Outcomes: After participating in this program, students will have a better understanding of the Underground Railroad, various viewpoints on the issue of slavery, and what life was like in the mid-1800s. Standards Connections: National Standards NCTE – ELA K-12.4 Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes. NCTE – ELA K-12.12 Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information). NCSS - SS.2 Time, Continuity, and Change NCSS - SS.5 Individuals, Groups, and Institutions NCSS - SS.6 Power, Authority, and Governance NCSS - SS.8 Science, Technology, and Society Ohio Revised Standards – Social Studies Grade Four Theme: Ohio in the United States Topic: Heritage Content Statement 7: Sectional issues divided the United States after the War of 1812. Ohio played a key role in these issues, particularly with the anti-slavery movement and the Underground Railroad. 1 Topic: Human Systems Content Statement 13: The population of the United States has changed over time, becoming more diverse (e.g., racial, ethnic, linguistic, religious). -

Northern Terminus: the African Canadian History Journal

orthern Terminus: N The African Canadian History Journal Mary “Granny” Taylor Born in the USA in about 1808, Taylor was a well-known Owen Sound vendor and pioneer supporter of the B.M.E. church. Vol. 17/ 2020 Northern Terminus: The African Canadian History Journal Vol. 17/ 2020 Northern Terminus 2020 This publication was enabled by volunteers. Special thanks to the authors for their time and effort. Brought to you by the Grey County Archives, as directed by the Northern Terminus Editorial Committee. This journal is a platform for the voices of the authors and the opinions expressed are their own. The goal of this annual journal is to provide readers with information about the historic Black community of Grey County. The focus is on historical events and people, and the wider national and international contexts that shaped Black history and presence in Grey County. Through essays, interviews and reviews, the journal highlights the work of area organizations, historians and published authors. © 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microreproduction, recording or otherwise – without prior written permission. For copies of the journal please contact the Archives at: Grey Roots: Museum & Archives 102599 Grey Road 18 RR#4 Owen Sound, ON N4K 5N6 [email protected] (519) 376-3690 x6113 or 1-877-473-9766 ISSN 1914-1297, Grey Roots Museum and Archives Editorial Committee: Karin Noble and Naomi Norquay Cover Image: “Owen Sound B. M. E. Church Monument to Pioneers’ Faith: Altar of Present Coloured Folk History of Congregation Goes Back Almost to Beginning of Little Village on the Sydenham When the Negros Met for Worship in Log Edifice, “Little Zion” – Anniversary Services Open on Sunday and Continue All Next Week.” Owen Sound Daily Sun Times, February 21, 1942. -

The Serpent of Lust in the Southern Garden: the Theme of Miscegenation in Cable, Twain, Faulkner and Warren

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1973 The eS rpent of Lust in the Southern Garden: the Theme of Miscegenation in Cable, Twain, Faulkner and Warren. William Bedford Clark Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Clark, William Bedford, "The eS rpent of Lust in the Southern Garden: the Theme of Miscegenation in Cable, Twain, Faulkner and Warren." (1973). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2451. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2451 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

PART 1 Rresistanceesistance to Sslaverylavery

PART 1 RResistanceesistance to SlaverySlavery A Ride for Liberty, or The Fugitive Slaves, 1862. J. Eastman Johnson. 55.9 x 66.7 cm. Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York. “You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man.” —Frederick Douglass Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave 329 J. Eastman Johnson/The Bridgeman Art Library 0329 U3P1-845481.indd 329 4/6/06 9:00:01 PM BEFORE YOU READ Three Spirituals WHO WROTE THE SPIRITUALS? he spirituals featured here came out of the oral tradition of African Americans Tenslaved in the South before the outbreak of the Civil War. These “sorrow songs,” as they were called, were created by anonymous artists and transmitted by word of mouth. As a result, several versions of the same spiritual may exist. According Some spirituals served as encoded messages by to the Library of Congress, more than six thousand which enslaved field workers, forbidden to speak spirituals have been documented, though some are to each other, could communicate practical infor- not known in their entirety. mation about escape plans. Some typical code African American spirituals combined the tunes words included Egypt, referring to the South or the and texts of Christian hymns with the rhythms, state of bondage, and the promised land or heaven, finger-snapping, clapping, and stamping of tradi- referring to the North or freedom. To communi- tional African music. The spirituals allowed cate a message of hope, spirituals frequently enslaved Africans to retain some of the culture of recounted Bible stories about people liberated from their homelands and forge a new culture while fac- oppression through divine intervention. -

Fannie Lou Hamer's Pastoral and Prophetic Styles of Leadership As

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers 2015 Tell It On the Mountain: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Pastoral and Prophetic Styles of Leadership as Acts of Public Prayer Breanna K. Barber University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/utpp Part of the Women's History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Barber, Breanna K., "Tell It On the Mountain: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Pastoral and Prophetic Styles of Leadership as Acts of Public Prayer" (2015). Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers. 29. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/utpp/29 This Professional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TELL IT ON THE MOUNTAIN: FANNIE LOU HAMER’S PASTORAL AND PROPHETIC STYLES OF LEADERSHIP AS ACTS OF PUBLIC PRAYER By BREANNA KAY BARBER Undergraduate Professional Paper presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2015 Approved by: Dr. Tobin Miller-Shearer, African-American Studies ABSTRACT Barber, Breanna, Bachelor of Arts, May 2015 History Tell It On the Mountain: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Pastoral and Prophetic Styles of Leadership as Acts of Public Prayer Faculty Mentor: Dr. Tobin Miller-Shearer Fannie Lou Hamer grew up in an impoverished sharecropping family in Ruleville, Mississippi. -

Go Down Moses

Go down moses Continue This article is about the song. The book by William Faulkner can be found under Go Down, Moses (book). Go Down, MosesSong by Fisk Jubilee Singers (early testified)GenreNegro spiritualSongwriter(s)Unknown Go Down Moses problems playing this file? See Media Help. Go down Moses is a spiritual proposition that describes the events in the Old Testament of the Bible, especially Exodus 8:1: And the LORD said to Moses, Go to Pharaoh and say to him, Thus says the LORD, Let my people go, that they may serve me, in which God commands Moses to demand the deliverance of the Israelites from bondage in Egypt. The opening verse that the Jubilee Singers published in 1872: When Israel was in the Egyptian land, let my people go so hard that they couldn't stand Let my people go: Go down, Moses Way down into Egypt's land Say to the old Pharaoh, let my people go The lyrics of the song stand for the liberation of the ancient Jewish people from Egyptian slavery. In an interpretation of the song, Israel depicts enslaved African-Americans, while Egypt and Pharaoh represent the slave master. [1] The descent into Egypt is derived from the Bible; the Old Testament recognizes the Nile Valley as lower than Jerusalem and the Promised Land; so it means going to Egypt to go down[2] while going away from Egypt is ascending. [3] In the context of American slavery, this old sense of down converged with the concept of down the river (the Mississippi), where the conditions of slaves were notoriously worse, a situation that led to the idiom selling someone down the river in today's English. -

Hidden Messages in Spirituals Intermediate (Grades 6-8) 1-2 Class Periods

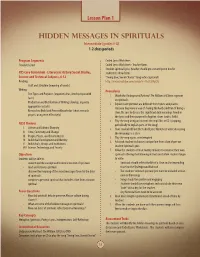

Lesson Plan 1 Hidden Messages in Spirituals Intermediate (grades 6-8) 1-2 class periods Program Segments Coded Lyrics Worksheet Freedom’s Land Coded Lyrics Worksheet - Teacher Notes Student Spiritual Lyrics (teacher should pre-cut and put in box for NYS Core Curriculum - Literacy in History/Social Studies, students to draw from) Science and Technical Subjects, 6-12 “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” Song video (optional) Reading http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Thz1zDAytzU • Craft and Structure (meaning of words) Writing Procedures • Test Types and Purposes (organize ideas, develop topic with 1. Watch the Underground Railroad: The William Still Story segment facts) on spirituals. • Production and Distribution of Writing (develop, organize 2. Explain how spirituals are different from hymns and psalms appropriate to task) because they were a way of sharing the hard condition of being a • Research to Build and Present Knowledge (short research slave. Be sure to discuss the significant dual meanings found in project, using term effectively) the lyrics and their purpose for fugitive slaves (codes, faith). 3. Play the song using an Internet site, mp3 file, or CD. (stopping NCSS Themes periodically to explain parts of the song) I. Culture and Cultural Diversity 4. Have students fill out the Coded Lyrics Worksheet while discussing II. Time, Continuity and Change the meanings as a class. III. People, Places, and Environments 5. Play the song again, uninterrupted. IV. Individual Development and Identity 6. Ask each student to choose a unique line from a box of pre-cut V. Individuals, Groups and Institutions VIII. Science, Technology, and Society Student Spiritual Lyrics. -

Spirituals As a Source of Inspiration and Motivation

http://ctl.du.edu/spirituals/Freedom/source.cfm SPIRITUALS AS A SOURCE OF INSPIRATION AND MOTIVATION One important purpose of many spirituals during the slave period was to provide motivation and inspiration for the ongoing struggle for freedom, a struggle which included systematic efforts to escape5 from bondage as well as numerous slave-led revolts and insurrections6. In the African tradition, stories of ancestors’ bravery, victories in battle, and success in overcoming past hardships were often marshaled as inspiration to face current life challenges. As stories of specific African ancestors faded over time, enslaved people appropriated heroes from the Christian Bible as ancestral equivalents7. The stories of Old Testament figures – often perceived by enslaved Africans as freedom fighters – held particular significance as models of inspiration. For example, a surviving spiritual entitled “Moses,” and still sung today in the Georgia Sea Islands, draws its inspiration from the Biblical story of Moses, commanded by God to lead the Hebrew people out of Egyptian bondage. [Harriet Tubman, the famous Underground Railroad conductor was known as Moses by many slaves. As another example, “Go Down, Moses,” similar in meaning to “Moses, Moses,” has been a staple of the concert spirituals tradition that has featured solo artists and choral ensembles in world-wide performances dating back to the 1870s tours of the Fisk Jubilee Singers8, and continuing with the performances of diverse artists and ensembles up to the present day. The singer-activist Paul Robeson, for example, sang “Go Down, Moses” frequently in his concerts, and his comments about spirituals as songs of inspiration in the continuing struggle for freedom9 were very much in line with the tradition of spirituals as songs of inspiration and motivation during the slave period. -

Slavery in New Jersey Lesson Plan

Elementary School | Grades 3–5 SLAVERY IN NEW JERSEY ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS What was the Underground Railroad and how did it help enslaved people gain their right of freedom? What role did the people of New Jersey play in the Underground Railroad and the struggle against slavery? OBJECTIVES Students will: → Describe the Underground Railroad and its significance in the abolition of chattel slavery. → Investigate Harriet Tubman’s role as a leader in the Underground Railroad. → Explore New Jersey’s role in the Underground Railroad and map key stops along the route. LEARNING STANDARDS See the standards alignment chart to learn how this lesson supports New Jersey State Standards. TIME NEEDED 45 minutes MATERIALS → AV equipment to show a video → On Track or Off the Rails? handout (one per student or one copy to read aloud) → On Track or Off the Rails Cards handout (copied and cut apart so each student gets one of each card) → Underground Railroad Routes in New Jersey handout (one per student or pair) → New Jersey Stops on the Underground Railroad handout (one per student) VOCABULARY abolitionist enslaver Quaker enslaved plantation Underground Railroad 72 Procedures 2 NOTE ABOUT LANGUAGE When discussing slavery with students, it is suggested the term “enslaved person” be used instead of “slave” to emphasize their humanity; that “enslaver” be used instead of “master” or “owner” to show that slavery was forced upon human beings; and that “freedom seeker” be used instead of “runaway” or “fugitive” to emphasize justice and avoid the connotation of lawbreaking. Write “Underground Railroad” on the board. Ask students if 1 they have ever heard this term and what they know about it. -

Harriet Tubman: Conductor on the Underground Railroad

BIOGRAPHY from Harriet Tubman CONDUCTOR ON THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD by Ann Petry How much should a person sacrifi ce for freedom? QuickTalk How important is a person’s individual freedom to a healthy society? Discuss with a partner how individual freedom shapes American society. Harriet Tubman (c. 1945) by William H. Johnson. Oil on paperboard, sheet. 29 ⁄" x 23 ⁄" (73.5 cm x 59.3 cm). 496 Unit 2 • Collection 5 SKILLS FOCUS Literary Skills Understand characteristics Reader/Writer of biography; understand coherence. Reading Skills Notebook Identify the main idea; identify supporting sentences. Use your RWN to complete the activities for this selection. Vocabulary Biography and Coherence A biography is the story of fugitives (FYOO juh tihvz) n.: people fl eeing someone’s life written by another person. We “meet” the people in from danger or oppression. Traveling by a biography the same way we get to know people in our own lives. night, the fugitives escaped to the North. We observe their actions and motivations, learn their values, and incomprehensible (ihn kahm prih HEHN see how they interact with others. Soon, we feel we know them. suh buhl) adj.: impossible to understand. A good biography has coherence—all the details come The code that Harriet Tubman used was together in a way that makes the biography easy to understand. incomprehensible to slave owners. In nonfi ction a text is coherent if the important details support the incentive (ihn SEHN tihv) n.: reason to do main idea and connect to one another in a clear order. something; motivation. The incentive of a warm house and good food kept the Literary Perspectives Apply the literary perspective described fugitives going. -

Viewing Guide

VIEWING GUIDE RAPPAHANNOCK COUNTY Harrison Opera House, Norfolk What’s Inside: VAF Sponsors 2 Historical Sources 8 About the Piece 3 Civil War Era Medicine 9 The Voices You Will Hear 4 Real Life Civil War Spies 10 What is Secession? 5 What is Contraband? 11 Topogs 6 Music During the Civil War 12-13 Manassas 7 Now That You’ve Seen Rappahannock County 14 vafest.org VAF SPONSORS 2 The 2011 World Premiere of Rappahannock County in the Virginia Arts Festival was generously supported by Presenting Sponsors Sponsored By Media Sponsors AM850 WTAR Co-commissioned by the Virginia Arts Festival, Virginia Opera, the Modlin Center for the Arts at the University of Richmond, and Texas Performing Arts at the University of Texas at Austin. This project supported in part by Virginia Tourism Corporation’s American Civil War Sesquicentennial Tourism Marketing Program. www.VirginiaCivilWar.org VIRGINIA ARTS FESTIVAL // RAPPAHANNOCK COUNTY ABOUT THE PIECE 3 RAPPAHANNOCK COUNTY A new music theater piece about life during the Civil War. Ricky Ian Gordon Mark Campbell Kevin Newbury Rob Fisher Composer Librettist Director Music Director This moving new music theater work was co- Performed by five singers playing more than 30 commissioned by the Virginia Arts Festival roles, the 23 songs that comprise Rappahannock th to commemorate the 150 anniversary of the County approach its subject from various start of the Civil War. Its creators, renowned perspectives to present the sociological, political, composer Ricky Ian Gordon (creator of the and personal impact the war had on the state of Obie Award-winning Orpheus & Euridice and Virginia. -

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’

Oxfam Education H www.oxfam.org.uk/education Oxfam Education H www.oxfam.org.uk/education Global Music Lesson Plans Lesson 4: Songs of Slavery – Africa, America and Europe. For ages 14-16. Time required: One 60 minute lesson. Activity: Singing, listening to and appraising songs of slavery. Aims: To explore the characteristics of ‘spirituals’. To analyse and appraise spirituals. Pupils will learn: How spirituals sung by slaves on American plantations often contained coded messages. How spirituals fuse characteristics of European hymns and African vocal techniques and rhythms to create a new style. To sing call and response melodies adding vocal harmonies. Web links you will need: Information about Negro spirituals. Sheet music to ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’. Audio file of ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’. Recording of an English congregational hymn. Songs of Praise almost always begins with a traditional hymn. Sheet music to ‘Go Down Moses’. Sheet music of ‘Follow the Drinking Gourd’. Other resources you will need: Lyric worksheet for ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’: Lyrics worksheet for ‘Go Down Moses’/ Lyrics worksheet for ‘Follow the Drinking Gourd’. Copyright © Oxfam GB. You may reproduce this document for educational purposes only. Page 1 Useful information Slave songs are an especially important resource for studying slavery, particularly as music that arises out of oppression often has a particular potency and poignancy. Spirituals contained the hopes and dreams, frustrations and fears, of generations of African Americans. It’s important to note that slavery still exists in forms such as bonded labour and human trafficking, and is still an ongoing issue in today’s world.