Teacher's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

PROGRAMS COLLEGE OF FELLOWS NOMINATIONS The Fellows Committee met twice in 2019 to steward Any Fellow can submit a Fellowship nomination. Please The Nominating Committee met on Oct. 9, 2019, and the increased frequency of public events AWARDS the nomination process for new Fellows. This year, the visit rcgs.org/fellows for more information on how to to review the Board positions that are to be filled were all recognized for their roles in the new Society has welcomed 133 new nominations for the nominate someone in 2020. at the Annual General Meeting, including those domestic and international status of the Society. To recognize outstanding achievement in the fields of exploration, geography, education and science, the College of Fellows. of the President and two Governors. Nominations for Governor were assessed with a Society presented the following awards to deserving individuals that made an impact in 2019. To learn more view to meeting these needs. about each award, recipient, or how to nominate someone in 2020, please visit rcgs.org/awards. The recommendations of the Committee will be ANNUAL ADVANCEMENT presented to the College of Fellows for election As we celebrate our 90th Anniversary, the at the Annual General Meeting in Ottawa on Nominating Committee is sensitive to the RT. HON. VINCENT MASSEY MEDAL SIR CHRISTOPHER ONDAATJE The RCGS is buoyed by the support of its community with an eye to improving donors’ experiences with the Nov. 20, 2019. impending 100th anniversary of the founding MEDAL FOR EXPLORATION Awarded to Derek Ford, geomorphologist. and their generous gifts to the Society. Individual organization. -

The Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line: a Bibliography and Documentary Resource List

The Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line: A Bibliography and Documentary Resource List Prepared for the Arctic Institute of North America By: P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Ph.D. Matthew J. Farish, Ph.D. Jennifer Arthur-Lackenbauer, M.Sc. October 2005 © 2005 The Arctic Institute of North America ISBN 1-894788-01-X The DEW Line: Bibliography and Documentary Resource List 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 PREFACE 2 2.0 BACKGROUND DOCUMENTS 3 2.1 Exchange of Notes (May 5, 1955) Between Canada and the United States Of America Governing the Establishment of a Distant Early Warning System in Canadian Territory.......................................................................................................... 3 2.2 The DEW Line Story in Brief (Western Electric Corporation, c.1960) ……………… 9 2.3 List of DEW Line Sites ……………………………………….…………………….... 16 3.0 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS 23 3.1 Rt. Hon. John George Diefenbaker Centre ……………………………………….…... 23 3.2 Library and Archives Canada …………………………………….…………………... 26 3.3 Department of National Defence, Directorate of History and Heritage ………………. 46 3.4 NWT Archives Council, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre ……………….... 63 3.5 Yukon Territorial Archives, Whitehorse, YT ………………………………………… 79 3.6 Hudson Bay Company Archives ……………………………………………………... 88 3.7 Archives in the United States ……………………………………………………….… 89 4.0 PUBLISHED SOURCES 90 4.1 The Globe and Mail …………………………………………………………………………… 90 4.2 The Financial Post ………………………………………………………………………….…. 99 4.3 Other Print Media …………………………………………………………………..… 99 4.4 Contemporary Journal Articles ……………………………………………………..… 100 4.5 Government Publications …………………………………………………………….. 101 4.6 Corporate Histories ………………………………………………………………...... 103 4.7 Professional Journal Articles ………………………………………………………..… 104 4.8 Books ………………………………………………………………………………..… 106 4.9 Scholarly and Popular Articles ………………………………………………….……. 113 4.10 Environmental Issues and Cleanup: Technical Reports and Articles …………….…. 117 5.0 OTHER SOURCES 120 5.1 Theses and Dissertations ……………………………………………………………... -

Geography & Exploration

50 SUSSEX CANADIAN The Society’s headquarters at iconic location unlike any other GEOGRAPHIC 50 Sussex Drive, Ottawa, is a in the National Capital Region. In EDUCATION building of national interest in one addition, extensive renovations of the most significant geographic and upgrades to the building’s The Society’s Canadian locations in the capital — an three below-ground levels mean Geographic Education CANADA’S CENTRE FOR unmatched combination of historic that 50 Sussex is today both a division creates its acclaimed and modern eras set against the landmark and a dynamic, globally bilingual grade-school curriculum backdrop of the Ottawa River, connected building incorporating and student programs for a GEOGRAPHY & Rideau Falls, and the Gatineau hills. innovative technology and spaces network of 21,000 K-12 teachers, New above-ground galleries that include a state-of-the-art and works with them to improve and boardroom and meeting 300-plus-seat theatre. geography teaching methods. EXPLORATION spaces have transformed For more information about Programs include the Canadian 50 Sussex into an exceptional events and space rental, Geographic Challenge, a national multi-use facility situated in an visit 50sussex.ca. quiz competition; the Classroom Energy Diet Challenge, in which classes compete for prize money to apply green technologies to their schools; Geography Awareness Week, with nationwide activities SUPPORTING THE SOCIETY each November; and the Giant The Royal Canadian Geographical Society has been inspiring Canadians to Floor Map Program, which makes learn more about their country since 1929. As a registered Canadian charity themed 8x11-metre maps avail- and non-profit educational organization, it would not be able to continue able to schools free of charge. -

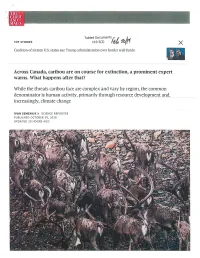

Globe and Mail Article on Caribou

Tabled Documents J; J .~ TOP STORIES 119-5(2) ttu 18,1'f x Coalition of sixteen U.S. states sue Trump administration over border wall funds Across Canada, caribou are on course for extinction, a prominent expert warns. What happens after that? While the threats caribou face are complex and vary by region, the common denominator is human activity, priInarily through resource developlnent and, increasingly, cliInate change IVAN SEMENIUK ) SCIENCE REPORTER PUBLISHED OCTOBER 29, 2018 UPDATED 20 HOURS AGO 'I Caribou from the Porcupine River herd on the move in the Yukon's Blow River Valley, WERONII<A MURRAY/THE GLOBE AND MAIL More below- Photo essay: Caribou, a Yukon way of life Caribou, the iconic herbivore that graces the back of the Canadian quarter, is on a pathway to extinction in every region where it is currently found, says one of the country's foremost experts on the species. The stark assessment has emerged from nearly a decade of meticulous research aimed at understanding how 11 different subsets or "designatable units" of caribou should be listed under the federal Species at Risk Act. Justina Ray, a conservation biologist who co-led the work on behalf of the independent body that advises the government on the status of endangered wildl~fe, said the change in the caribou's fortunes since 2004, the last time such an assessment was completed, is profoundly worrying. "I think the conclusions startle even those of us who have been paying a lot of attention," Dr. Ray told The Globe and Mail before a government-sponsored meeting of caribou researchers in Ottawa this week. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION In the 1960s, Canadian Roger Tomlinson made a major contribution to cartography when he created the world’s first geographic information system (GIS). Over the next 50 years, the GIS field has grown to become an essential part of today’s world. GIS is used by all levels of government and also in business, education, health, natural resources and many other areas. Most people benefit from Roger Tomlinson’s creation every day. Long before Tomlinson began his work, the explorer David Thompson put map-making to good use when, around 1800, he mapped a significant portion of Canada. The lessons that accompany this giant floor map highlight the importance of Tomlinson’s GIS discovery, as well as other significant geospatial technologies. The lessons also show the value of Thompson’s traditional maps and mapping skills. The 10 curriculum‐linked lesson plans will help you teach students essential topics such as map-reading skills while also helping them learn about the geography of Canada. These lessons will engage Canadian students with topical lessons on the Canadian Arctic, the Global Position- ing System (GPS) and the importance of GIS in today’s world. This giant floor map and lessons will help educators engage, foster and promote geographic literacy and help develop the next generation of geographers in Canada. You will see geospatial technologies referenced throughout the lessons. We encourage you to explore the options that are available to you in your school, school district or board. Enjoy your time with the map; it is yours to explore. Natural Resources Canada | Teacher’s Guide | Introduction | Page 1 ABOUT THIS RESOURCE THE ACTIVITIES In this guide, you will find 10 curriculum-linked activities designed for all Canadian students at the elementary and secondary levels. -

IN the CLASSROOM an Anti-Métis Agitator, on Riel’S Orders

DISCOVERY HISTORY This Map of the Province of Manitoba compiled by A.L. Russell in 1871 Glorious and free depicts the province less than a year after it joined Confederation. Celebrating Manitoba‘s 150th anniversary this summer with the oldest map of the province BY ANGELICA HAGGERT GOOD SANDY LOAM. A FOREST OF POPLARS. Beautiful fertile open prairie. Together these handwritten notes could describe none other than Manitoba at its inception, as shown on this 1871 map — the first depicting the province. At the time, the “postage stamp province,” as it was known, covered only about 36,000 square kilometres, roughly 18 times smaller than the Prairie and boreal province we know today. GWhile the area has for millennia been part of the traditional territories of the Assiniboine, Ojibwe and Dakota peoples in the south and the Cree and Dene in the north, the first Europeans to set foot in what would become Manitoba were 17th-century British migrants lured to the shores of Hudson Bay by a reported abundance of beaver pelts in a vast territory. After multiple ships returned to England with rich cargos of fur, a royal charter was signed to create the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670 and grant it control of Rupert’s Land, a giant territory covering about one-third of what is now Canada and all of present-day Manitoba. To say Manitoba’s entrance into Confederation 200 years later was hard-fought is an CANADIAN GEOGRAPHIC understatement. In the late 1800s, the newly minted Dominion of Canada and the United States were both vying to purchase Rupert’s Land. -

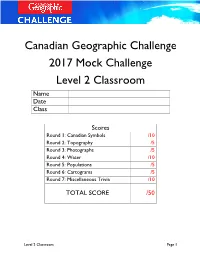

Questions Classroom.Pdf

Canadian Geographic Challenge 2017 Mock Challenge Level 2 Classroom Name Date Class Scores Round 1: Canadian Symbols /10 Round 2: Topography /5 Round 3: Photographs /5 Round 4: Water /10 Round 5: Populations /5 Round 6: Cartograms /5 Round 7: Miscellaneous Trivia /10 TOTAL SCORE /50 Level 2 Classroom Page 1 Round 1: Canadian Symbols ( /10) This round will test your knowledge of Canadian provincial, territorial, and national symbols. # Question Answer 1 The leaf of which tree appears on the Canadian flag? A) Birch B) Maple C) Elm D) Pine 2 Manitoba’s provincial animal, shown here, was once hunted nearly to extinction. What is the name of this animal? A) Plains Bison B) Wood Bison C) North American Moose D) Grizzly Bear 3 Which of the following provinces does not have a species of owl as its provincial bird? A) Quebec B) Saskatchewan C) Alberta D) British Columbia 4 An inukshuk can be found on which territorial flag? A) Nunavut B) Northwest Territories C) Yukon D) British Columbia 5 Which province’s flag features a lion and group of oak trees? A) Nova Scotia B) New Brunswick C) Newfoundland and Labrador D) Prince Edward Island Level 2 Classroom Page 2 # Question Answer 6 The common loon, which appears on the Canadian $1 coin, is the provincial bird of which province? A) Alberta B) British Columbia C) Quebec D) Ontario 7 What is the provincial mineral of Saskatchewan? A) Nickel B) Potash C) Amethyst D) Tin 8 Canada’s national motto is A Mari Usque Ad Mare. What does this translate to? A) True North Strong and Free B) From Sea to Sea C) Glorious and Free D) Our Land and Our Home 9 How many times does the fleur-de-lis appear on the Quebec flag? A) 1 B) 3 C) 4 D) 5 10 Which musical instrument appears on the Canadian coat of arms? A) Guitar B) Drum C) Harp D) Flute Level 2 Classroom Page 3 Round 2: Topography ( /5) This round will test your ability to analyze and interpret topographic maps and diagrams. -

Media Kit 2016

MEDIA KIT 2016 about us Giving Canadians a deeper knowledge of their country — its people and places, its natural and cultural heritage and its environmental, social and economic challenges Making Canada better known to Canadians and to the world Engaging over 3.662 million Canadians monthly across all platforms Pillars Photography • Adventure • Exploration Wildlife • Travel • Current issues Reader Profile Canadian Geographic reaches affluent, influential decision-makers, highly engaged with their communities and passionate about Canada and the world beyond Reach Canadian Geographic is the third-highest reaching publication in Canada and the second-highest reaching magazine brand digitally of adults 18+ PREVIOUS PAGE, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: ERIK BOOMER, CANADIAN GEOGRAPHIC APRIL 2014; JESSICA FINN/CAN GEO STAFF; JASON FULFORD/CAN GEO; CHRIS MACDONALD/CAN GEO PHOTO CLUB, CANADIAN GEOGRAPHIC BEST WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHY 2016; JESSICA FINN/CAN GEO STAFF; NICK HAWKINS/CAN GEO; SARAH MCNAIR-LANDRY, CANADIAN GEOGRAPHIC APRIL 2014; SIMON BOLYN/CAN GEO PHOTO CLUB, CANADIAN GEOGRAPHIC BIRDS PHOTOGRAPHY 2015. THIS PAGE: NICK HAWKINS/CAN GEO about us Giving Canadians a deeper knowledge of their country — its people and places, its natural and cultural heritage and its environmental, social and economic challenges The Royal Canadian Geographical Society Ð Founded in 1929 by geologist Charles Camsell with a Ð Maintains a wide range of education, research and mandate of “making Canada better known to Canadians exploration programs: and to the world” Ì Canadian -

GREAT L Lgs EDUCATION MATERIAL DIRECTORY of GREAT LARES EDUCATION MA!Z'!ERW

DIBmmOF GREAT L_lgS EDUCATION MATERIAL DIRECTORY OF GREAT LARES EDUCATION MA!Z'!ERW Published by the Great Lakes Scknce Advisory Board International Joint Commission 1987; reprinted 1988; 1989 Welcome to the third edition of the Dimdory of Gmat Laks Education Materid. lhis pr+d began in 1984, when the Science Advieory Board's Socioeconomics Subcommittee surveyed sevaral hundred educatore and producers of educational programe to determine what matenials they fbund moet ueeful in teaching others about the Great Lakee. The goal of the eurvey wae to deternine wht items were available, and which were used moet often for variow eubject areae and gxwlw. Resub of thie survey were tabulated, and a followup questionnaire was eent in early 1987 to update ~e- eponeee to produce the first edition of thie directory. The eecond edition in 1988 included minor updates to the lietinge. To produce this latest edition, more than 600 educators were emeyed to determine whether there hae been an increase in the type and amount of materials available on the Great Lakes, ae well ae the frequency with which teachers are using these materials. What we found ie encouraging. First, more information is being produced. The wide variety of pamphlets, technical reparts and booklets available from government agencies, environmental organizations and scientific bodies continues to expand, and teachem still find thie information ueeful in developing their own educa- tional progxame. Second, thie information d materiale written epecifically for the educational eetting are getting into teachere' hande more quickly, and &om a wider variety of eourcee. The survey responees hopefully show that greater marketing efforts are being expended to get Great Lakee materiale into the claesroorn, and that teachers are eeebing out information on the lakee more than they were even two wars ago. -

Threats to Canada's Critical Infrastructure

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. Number: TA03-001 TTTHHHRRREEEAAATTT AAANNNAAALLLYYYSSSIIISSS Date: 12 March 2003 Threats to Canada’s Critical Infrastructure Purpose The purpose of this paper on Threats to Canada’s Critical Infrastructure is to provide a taxonomy of the natural, accidental and malicious threats that have been identified as those most likely to impact upon Canada’s national critical infrastructure. -

Marine Environmental Prediction in the Atlantic Coastal Region

CANADIAN OCEAN SCIENCE NEWSLETTER LE BULLETIN CANADIEN DES SCIENCES DE L'OCÉAN Table of Contents, Newsletter Number 32, October 18, 2007 Table des matières, Bulletin numéro 32, 18 octobre 2007 JOBS: • No submissions OCEAN SCIENCE PROGRAMS • SCOR Working Group 125, “Global Comparisons of Zooplankton Time Series” PERSONNEL: • Eddy Carmack Awarded the 2007 Massey Medal MEETINGS: • ArcticNet, Fourth Annual Scientific Meeting • Arctic Council Working Group meeting of PAME • CALL FOR PAPERS: CZC 2008 GENERAL: • ATMOSPHERE-OCEAN invites submissions • Back Issues of OCEANOGRAPHY • The Sangster Award SCOR Working Group 125, “Global Comparisons of Zooplankton Time Series” Updated Status Report from Dave Mackas, [email protected] Most members attended the second WG 125 meeting, held 4-7 December 2006 in Miraflores Peru, prior to the Humboldt Current Symposium. Many were also able to participate in a brief supplementary WG meeting, held 26-27 May 2007 in Hiroshima Japan, prior to the 4th International Zooplankton Production Symposium. The Hiroshima Symposium also saw 14 papers authored/coauthored by WG125 members presented in the first of 10 topic sessions (“Global comparison of zooplankton time series”; convened by WG members Mackas and Valdes). There were two main discussion topics during the May 07 WG meeting. The first was development and testing of “tool kit” software and statistical methodologies for calculating seasonal climatologies (and anomalies relative to these) for our variety of spatial and temporal sampling designs (single location time series vs. line transects vs. irregular grids within statistical regions). We now have access to three long zooplankton data sets with very high temporal resolution (Plymouth L4, Helgoland Roads, and Bay of Naples). -

Media Kit 2019

MEDIA KIT 2019 JAVIER FRUTOS/ CANGEO PRINT HISTORY CONTENT Award-winning journalism focused Explores topics including photography, on Canada and its cultural adventure, exploration, wildlife, travel and natural heritage since 1930 and current issues 3.1 million readers per issue Highlights annual expeditions Vividata, 2018 12+ Renown for its storytelling, photography and cartography Won Gold at the 2018 National Magazine Awards for Long-Form Gives Canadians a deeper knowledge Feature Writing — Trash Nation of their country Won Gold at the 2018 National Magazine Awards for Canadian READERS Geographic’s Indigenous Languages of Canada poster map Reaches affluent, influential decision-makers, highly engaged with A powerful premium brand their communities and passionate that reflects values widely shared about Canada and the world beyond by Canadians and that exists on Read by people who enjoy camping, multiple print and digital platforms hiking, canoeing, and bike riding COVER IMAGE: NICK HAWKINS/CAN GEO PRINT HISTORY CONTENT Award-winning travel writing and Explores topics such as luxury, journalism about incredible experiences urban and adventure travel, in Canada and around the world cruises, hotels, food and drink, and gear and technology One of Canada’s most read through engaging stories told magazines with more than by some of the best writers and 3.1 million readers per issue photographers in Canada. Exposes readers to travel experiences A powerful premium brand that that are not just memorable but also focuses on telling both aspirational