The Greek Diaspora in the Soviet Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ust Dergi Sayi 17 Layout 1

THE FABRICATED PONTUS NARRATIVE AND HATE SPEECH Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN Ph.D. Candidate Department of Political Science and Public Administration Bilkent University Abstract: This article aims to examine the genocide story invented during the late 1980’s and 90’s called the “Pontic Greek Genocide” by way of referring both to the Greek academic sources and Pontic Greek allegations. This article also examines this invented story by referring to the Turkish evaluation of the “Pontus question” before, during, and after the World War I with a special emphasis on the period corresponding to the establishment of the Republic of Turkey. In this general framework, this article reviews the ethnic background of the 165 Pontic Greeks, the fragmentation of the Byzantine Empire and its successor states, the conquest of the Greek Trebizond Empire by the Ottoman Empire, Pontus Greek narratives and claims concerning the World War I developments, Pontic Greek activities and efforts to establish a Pontian state during World War I, and the invented story of genocide. It also elaborates the elements of the hate speech developed against Turks on the basis of the fabricated “Pontic Greek Genocide”. Keywords: Pontus, Pontian Narrative, Byzantine Empire, Ottoman Empire, Republic of Turkey, Hate Speech ÜRETİLMİŞ PONTUS ANLATISI VE NEFRET SÖYLEMİ Öz: Bu makale, 1980’li yılların sonlarından bu yana olgulara dayanmayan bir şekilde öne sürülmeye başlanan, “Pontus Rum Soykırımı” anlatısına odaklanmaktadır. Makale bu soykırım anlatısını, bu anlatıyı kabul eden ve etmeyen iki tarafın kaynaklarına atıfta bulunarak incelemektedir. Taraflardan bir tanesinin kaynakları, Yunan akademik çalışmaları, bir kısım Yunan elitinin iddiaları ve Birinci Dünya Savaşı gelişmeleri ile ilgili Pontus Rum anlatımlarından ve International Crimes and History, 2016, Issue: 17 Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN iddialarından oluşmaktadır. -

Chapter 7. Remembering Them

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2017-02 Understanding Atrocities: Remembering, Representing and Teaching Genocide Murray, Scott W. University of Calgary Press http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51806 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNDERSTANDING ATROCITIES: REMEMBERING, REPRESENTING, AND TEACHING GENOCIDE Edited by Scott W. Murray ISBN 978-1-55238-886-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Colloquia Pontica Volume 10

COLLOQUIA PONTICA VOLUME 10 ATTIC FINE POTTERY OF THE ARCHAIC TO HELLENISTIC PERIODS IN PHANAGORIA PHANAGORIA STUDIES, VOLUME 1 COLLOQUIA PONTICA Series on the Archaeology and Ancient History of the Black Sea Area Monograph Supplement of Ancient West & East Series Editor GOCHA R. TSETSKHLADZE (Australia) Editorial Board A. Avram (Romania/France), Sir John Boardman (UK), O. Doonan (USA), J.F. Hargrave (UK), J. Hind (UK), M. Kazanski (France), A.V. Podossinov (Russia) Advisory Board B. d’Agostino (Italy), P. Alexandrescu (Romania), S. Atasoy (Turkey), J.G. de Boer (The Netherlands), J. Bouzek (Czech Rep.), S. Burstein (USA), J. Carter (USA), A. Domínguez (Spain), C. Doumas (Greece), A. Fol (Bulgaria), J. Fossey (Canada), I. Gagoshidze (Georgia), M. Kerschner (Austria/Germany), M. Lazarov (Bulgaria), †P. Lévêque (France), J.-P. Morel (France), A. Rathje (Denmark), A. Sagona (Australia), S. Saprykin (Russia), T. Scholl (Poland), M.A. Tiverios (Greece), A. Wasowicz (Poland) ATTIC FINE POTTERY OF THE ARCHAIC TO HELLENISTIC PERIODS IN PHANAGORIA PHANAGORIA STUDIES, VOLUME 1 BY CATHERINE MORGAN EDITED BY G.R. TSETSKHLADZE BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 All correspondence for the Colloquia Pontica series should be addressed to: Aquisitions Editor/Classical Studies or Gocha R. Tsetskhladze Brill Academic Publishers Centre for Classics and Archaeology Plantijnstraat 2 The University of Melbourne P.O. Box 9000 Victoria 3010 2300 PA Leiden Australia The Netherlands Tel: +61 3 83445565 Fax: +31 (0)71 5317532 Fax: +61 3 83444161 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Illustration on the cover: Athenian vessel, end of the 5th-beg. of the 4th cent. -

Svetlana Berikashvili. Morphological Aspects of Pontic Greek Spoken in Georgia

106 | Reviews Svetlana Berikashvili. Morphological Aspects of Pontic Greek Spoken in Georgia. München: LINCOM, 2017, 163 pp. ISBN 978-3-86288-852-8. Angela Ralli Over the last decades, documenting dialects and generally non-standard lan- guages has witnessed an increasing interest, especially when these linguistic systems face the threat of extinction. Th e publication of the book Morphological Aspects of Pontic Greek Spoken in Georgia is very timely, because it provides a rather detailed account of the morphology of a variety of the Pontic group, the idiosyncratic features of which have been relatively unknown. Taking into consideration the main existing proposals for both Greek and Pontic morphology, Berikashvili provides a thorough presentation of her ma- terial, and at the same time raises a lot of questions regarding the infl uence that the variety has received from the languages that has entered in contact with, mainly Turkish and Russian, and to a lesser extent Georgian and Standard Modern Greek. Although she does not off er any sound theoretical analyses of the data, she encourages the debate on several issues on Pontic morphology, particularly on those regarding infl ection, and shows that there are “several av- enues” for further developments in the study of contact morphology, if dialects are accounted for as a testing bed for validating theoretical proposals. All scholars may not agree with some of the possible explanations put for- ward by the author, such as for instance, the division in infl ectional classes of nouns (pp. 36–47), or the realization of the perfective stem in verbal forms (pp. -

The Displacement, Extinction and Genocide of the Pontic Greeks. 1916-1923

H-War The Displacement, Extinction and Genocide of the Pontic Greeks. 1916-1923. Discussion published by Jesko Banneitz on Monday, February 1, 2016 Type: Conference Date: February 25, 2016 to February 26, 2016 Location: Germany Subject Fields: Area Studies, Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies, Islamic History / Studies, Nationalism History / Studies, Political History / Studies "The Displacement, Extinction and Genocide of the Pontic Greeks. 1916-1923." International Conference Berlin, Germany 25/26 February 2016 Over the last years, the genocide committed against the Armenians has received more and more scientific and popular attention. Thanks to a growing number of international scientists devoted to the elucidation and reappraisal of the Armenian-Ottoman past the historical processes leading to the extinction of the majority of the Armenian population within the Ottoman Empire have been traced and investigated. However, as recent international research has emphasized, the Armenian genocide by the Young-Turkish government has to be understood as only one chapter of an overall campaign of the Young-Turkish and Kemalist government against the non-Muslim (and later non-Turkish) communities. Besides the Armenians, particularly Greek communities in Asia Minor were affected most in terms of forced migration and atrocities, committed in the interests of specific Young-Turkish and Kemalist visions of the Ottoman space between 1913 and 1923. In this regard, the governmental campaign reached its violent climax in the genocide of the Greek communities in the Pontic area at the shores of the Black Sea. Albeit the killing of the Pontic Greek has become increasingly prominent in Anglo-American historical research, it still continues to be a desideratum within the European field of research. -

American Protestantism and the Kyrias School for Girls, Albania By

Of Women, Faith, and Nation: American Protestantism and the Kyrias School For Girls, Albania by Nevila Pahumi A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor Pamela Ballinger, Co-Chair Professor John V.A. Fine, Co-Chair Professor Fatma Müge Göçek Professor Mary Kelley Professor Rudi Lindner Barbara Reeves-Ellington, University of Oxford © Nevila Pahumi 2016 For my family ii Acknowledgements This project has come to life thanks to the support of people on both sides of the Atlantic. It is now the time and my great pleasure to acknowledge each of them and their efforts here. My long-time advisor John Fine set me on this path. John’s recovery, ten years ago, was instrumental in directing my plans for doctoral study. My parents, like many well-intended first generation immigrants before and after them, wanted me to become a different kind of doctor. Indeed, I made a now-broken promise to my father that I would follow in my mother’s footsteps, and study medicine. But then, I was his daughter, and like him, I followed my own dream. When made, the choice was not easy. But I will always be grateful to John for the years of unmatched guidance and support. In graduate school, I had the great fortune to study with outstanding teacher-scholars. It is my committee members whom I thank first and foremost: Pamela Ballinger, John Fine, Rudi Lindner, Müge Göcek, Mary Kelley, and Barbara Reeves-Ellington. -

<I>The World's Major Languages</I>

Journal of Greek Linguistics 9 (2009) 187–194 brill.nl/jgl Discussion Note Why Greek is one of Th e World’s Major Languages* Brian D. Joseph Department of Linguistics, Th e Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210-1298, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Th e inclusion of Greek in Bernard Comrie’s edited volume Th e World’s Major Languages (Croom Helm, 1987; second edition, Routledge, 2008) prompts the question of why Greek was so des- ignated. Two arguments supporting the editor’s choice are presented here by way of assessing the place and status of Greek among languages of the world, off ering some thoughts on the notion of “major language”, and considering the question of whether Greek constitutes “one language”. Keywords diachrony; dialects; language unity; major language ; Nobel Prize; sociology of language In 1987, Croom Helm Publishers of England brought out a book entitled Th e World’s Major Languages , edited by Bernard Comrie. It was updated recently and a second edition has now appeared, being published in 2008 by Routledge. Th e book contains descriptions of 40 languages considered by the editor to be “major languages”. Th e 40 languages (grouped here roughly by geography and language family) are Malay, Tagalog, Korean, Japanese, Burmese, Chinese, Vietnamese, Th ai, Tamil, Turkish, Arabic, Hebrew, Hausa, Swahili, Yoruba, Finnish, Hungarian, Bengali, Hindi, Sanskrit, Pashto, Persian, Czech, Polish, Russian, Serbo-Croatian, Slovak, French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, Spanish, Latin, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, Dutch, English, German, and Greek. * Preliminary versions of this discussion note were presented at the University of Patras (March 31, 2007) and St. -

The Ethnic History of the Greeks of Mariupol’: Problems and Prospects

ЕТНІЧНА ІСТОРІЯ НАРОДІВ ЄВРОПИ Irina PONOMAREVA Kyiv THE ETHNIC HISTORY OF THE GREEKS OF MARIUPOL’: PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS The Greeks of Mariupol’ living on the Azov area of Ukraine take their roots from the town they founded. In the year of 1778 the Christian Greeks of the Crimean Khanate moved on to the territory of Mariupol’ district of Ekaterinoslav province. They were headed by Metropolitan Ignatiy, the initiator of the migration. Having abandoned their prosperous Crimea, 18 thousand Greeks obtained an administrative and religious autonomy in the Azov area. Nowadays the number of Greeks living in Donetsk region run third in its ethnic structure (1,6 %). According to the population roll of 1989 the number of Greeks equaled 98 thousand people1, but according to the population roll of 2001 the number decreased to 92,6 thousand people2 due to migrations to Greece. The scientific interest lies in the fact that over a long period of time the Greeks have preserved their culture, traditions and language while being a constituent of various ethnic and social systems such as the Byzantine and the Osmanic Empires. Besides, another ethnic environment hasn’t affected the transformation of their selfconsciousness badly. The investigation of the ethnic processes that take place among the Greeks of the Azov area make it possible to typify the most complicated phenomena in the international interactions and in the intensity of the national and the cultural identity. Several stages of the ethnic history of the Greeks of Mariupol’ have been described in various reviews and research works, but still there are a lot of aspects that require a complex investigation. -

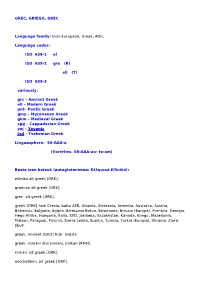

GREC, GRIEGO, GREC Language Family

GREC, GRIEGO, GREC Language family: Indo-European, Greek, Attic. Language codes: ISO 639-1 el ISO 639-2 gre (B) ell (T) ISO 639-3 variously: grc – Ancient Greek ell – Modern Greek pnt– Pontic Greek gmy – Mycenaean Greek gkm – Medieval Greek cpg – Cappadocian Greek yej – Yevanic tsd – Tsakonian Greek Linguasphere: 56-AAA-a (Varieties: 56-AAA-aa- to-am) Beste izen batzuk (autoglotonimoa: Ελληνικά Ellīniká): ellinika alt greek [GRK]. graecae alt greek [GRK]. grec alt greek [GRK]. greek [GRK] hizk Grezia; baita AEB, Albania, Alemania, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Bulgaria, Egipto, Erresuma Batua, Errumania, Errusia (Europa), Frantzia, Georgia, Hego Afrika, Hungaria, Italia, KED, Jordania, Kazakhstan, Kanada, Kongo, Mazedonia, Malawi, Paraguai, Polonia, Sierra Leona, Suedia, Tunisia, Turkia (Europa), Ukraina, Zipre, Jibuti. greek, ancient [GKO] hizk. Grezia. greek, romani dial romani, balkan [RMN]. romaic alt greek [GRK]. neo-hellenic alt greek [GRK]. ALBANIA greek [GRK] 60.000 hiztun, populazioaren % 1,8 (1989). Hegoaldea. Indo-European, Greek, Attic. Ikus sarrera nagusia Grezian. EGIPTO greek [GRK] 60.000 hiztun (1977, Voegelin and Voegelin). Alexandria. Indo-European, Greek, Attic. Ikus sarrera nagusia Grezian. ERRUMANIA greek [GRK] Indo-European, Greek, Attic. Karakatxanak grekos mintzatzen diren errumaniar artzain nomadak dira. GREZIA greek (ellinika, grec, graecae, romaic, neo-hellenic) [GRK] 9.859.850 hiztun, populazioaren % 98,5 (1986). Herrialde guztietako populazio osoa 12.000.000 (1999, WA). Herrialdean zehar. Halaber mintzatua beste 35 herrialdetan, hala nola AEB, Albania, Alemania, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Bulgaria, Egipto, Erresuma Batua, Errumania, Errusia (Europa), Frantzia, Georgia, Hego Afrika, Hungaria, Italia, KED, Jordania, Kazakhstan, Kanada, Kongo, Mazedonia, Malawi, Paraguai, Polonia, Sierra Leona, Suedia, Tunisia, Turkia (Europa), Ukraina, Zipre eta Jibutin ere. -

NOSTALGIA, EMOTIONALITY, and ETHNO-REGIONALISM in PONTIC PARAKATHI SINGING by IOANNIS TSEKOURAS DISSERTATION Submitted in Parti

NOSTALGIA, EMOTIONALITY, AND ETHNO-REGIONALISM IN PONTIC PARAKATHI SINGING BY IOANNIS TSEKOURAS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Donna A. Buchanan, Chair Professor Emeritus Thomas Turino Professor Gabriel Solis Professor Maria Todorova ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the multilayered connections between music, emotionality, social and cultural belonging, collective memory, and identity discourse. The ethnographic case study for the examination of all these relations and aspects is the Pontic muhabeti or parakathi. Parakathi refers to a practice of socialization and music making that is designated insider Pontic Greek. It concerns primarily Pontic Greeks or Pontians, the descendants of the 1922 refugees from Black Sea Turkey (Gr. Pontos), and their identity discourse of ethno-regionalism. Parakathi references nightlong sessions of friendly socialization, social drinking, and dialogical participatory singing that take place informally in coffee houses, taverns, and households. Parakathi performances are reputed for their strong Pontic aesthetics, traditional character, rich and aesthetically refined repertoire, and intense emotionality. Singing in parakathi performances emerges spontaneously from verbal socialization and emotional saturation. Singing is described as a confessional expression of deeply personal feelings -

Excursion on the Euxine

University of North Florida UNF Digital Commons History Faculty Publications Department of History 1996 Excursion On The Euxine Theophilus C. Prousis University of North Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ahis_facpub Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Prousis, Theophilus C., "Excursion On The Euxine" (1996). History Faculty Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ahis_facpub/19 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 1996 All Rights Reserved EXCURSION ON THE EUXINE by Theophilus C. Prousis University of North Florida Neal Ascherson, Black Sea (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), ix, 306 pp. $23.00. The Black Sea, known as Pontus Euxinus or hospitable sea in ancient times, connects Europe to Asia and laps the shoreline of seven countries, Russia, Ukraine, Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey, Georgia, and Abkhazia. Settlers and traders from east, west, north, and south have been drawn to the Black Sea re- gion throughout history for its wealth of fish, grain, timber, fur, slaves, gold, and silver. Fed by six rivers, the Kuban, Don, Dnieper, Southern Bug, Dniester, and Danube, the Black Sea today comprises the world's largest body of lifeless sea water, the result of both natural and man-made causes, and extends "some 630 miles across from east to west and 330 miles from north to south--except at its 'waist', where the projecting peninsula of Crimea reduces the north-south dis- tance between the Crimean shore and Turkey to only 144 miles" (3). -

Uprootedness As an Ethnic Marker and the Introduction of Asia Minor As an Imaginary Topos in Greek Films

Uprootedness as an Ethnic Marker and the Introduction of Asia Minor as an Imaginary Topos in Greek Films Yannis G. S. Papadopoulos The 'Asia Minor Catastrophe' followed by the influx of Anatolian refugees is a seminal moment in modern Greek history that reshaped to a great extent Greek national identity. In the analysis that follows I will try to trace how the Ottoman past, the 'uprooting experience' and the refugees' effort to integrate into Greek society are represented in some Greek films of the 1960s and 1970s. These films bear testimony to the acculturation process that led to the development of an Asia Minor and Pontic ethnic identity. Moreover, they reflect the construction of divergent collective memories, which accommodated the refugee experience in the framework of twentieth-century Greek history. As various scholars have pointed out, ethnic identity is the result of a group's interaction with the taxonomies imposed on it by state agents and broader society and the fluctuation of the accepted boundaries of difference in a modern national state. Besides, Fredrik Barth noted that 'the nature of continuity of ethnic units depends on the maintenance of a boundary whose cultural features may change and yet the continuing dichotomization between members and outsiders allows us to specify the nature of continuity, and investigate the changing cultural form and content'.1 The Greek Orthodox inhabitants of Anatolia did not form a culturally homogeneous group although they participated in the common Ottoman culture.2 Even among Greek-speaking Christians, customs and dialect varied considerably from place to place and Turkish-speaking Christians often had more in common with their Muslim co-villagers than with the Christians from another village or region.