Markets and the Structure of the Housebuilding Industry: an International Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housebuilder & Developer

Housebuilder HbD & Developer August 2016 EDI’s Edinburgh mixed use scheme reinvents former brewery site Croydon MP takes on Housing and Planning Call for more creativity from centre on housing Features in this issue Supplement Plus the latest Eco & Green Products Doors, Windows & Conservatories news, events and Interiors products Landscaping & External Finishes Also this month Rainwater & Greywater Products HBD speaks to HBF’s John Stewart Structural Insulated Panels (SIPs) Exclusive column from Brian Berry www.hbdonline.co.uk Reader Enquiry 401 HbD Contents August 2016 23 HEADLINES Gavin Barwell appointed as 5 Housing and Planning Minister Brian Berry discusses an 7 SME housebuilding renaissance Government quality push backed 9 by LABC ALSO IN THIS ISSUE... Industry news 4 - 27 Events 19 Industry Movers 22 Product Focus 26 Doors, Windows & Conservatories Supplement 29 - 39 41 Choose high efficiency insulation, naturally Duncan Voice from Insulation Superstore looks at the reasons why construction specifiers are increasingly investing in the benefits of eco PRODUCTS insulation products. Appointments & News 26 Building Products & Services 28 Eco & Green Products 40 - 42 45 Smart looks, smart operation Finance & Insurance 42 - 43 Fires & Fireplaces 43 The ‘wow’ factor can be achieved in new homes combined with cost- Floors & Floor Coverings 43 effective smart lighting and audio control to provide the best of both worlds Glass & Glazing 44 for developers. One company is realising the benefits in several new schemes. Interiors 45 - 46 Kitchens & Appliances 46 - 47 Landscaping & External Finishes 46 - 50 Rainwater & Greywater Products 51 - 53 48 Roofing 53 - 54 Safe, secure and sustainable Smoke & Fire Protection 54 Paul Garlick of green wall systems company Mobilane looks at the challenge Stairs, Balustrades & Balconies 57 of installing boundaries that satisfy safety and security requirements, as well Stonework & Masonry 57 as being eco-friendly. -

Download Portfolio

Structural Composites Engineered for the 21st Century Version 2.0 Project Portfolio Contents RECENT PROJECTS 1 Stadiums + Arenas 2 Buildings 3 Bridges 4 Maritime 5 Offshore 6 Special Applications 7 Production RECENT PROJECTS 1 Stadiums + Arenas University of Delaware Project Type Terraces (bleachers) Whitney Stadium Renovation July 2019 Location Newark, Delaware, US Team HOK, EDiS, FEI Corporation, Barton Mallow SPS terrace (bleacher) units were used to re-profile the existing stands of the University’s nearly 50 year old stadium, using SPS’ innovative system of ‘overdecking’ the existing precast concrete rakers with newly designed and prefabricated modular bleacher stool sets. The rapid erection cycle saw 60-80 bleachers installed in a working day, at the rate of roughly 5-8 minutes per bleacher. Included in the project were 3,625 seats including wheelchair spaces, as well as prefabricated ADA platforms. SPS bleachers and components were delivered in eighteen 40ft open top containers – 28 bleacher units per container pre-stacked in building sequence. A long-reach high capacity crane was used to lift the SPS bleacher units over the upper bowl and installed from each side onto new steel beams. spstechnology.com Stadiums + Arenas USTA Billie Jean King Project Type Terraces (bleachers) Grandstand redevelopment National Tennis Center Location Flushing Meadows, New York, US Grandstand Stadium Team ROSETTI, WSP Global (NY), AECOM Hunt September 2017 The 2016 US Open Tennis Championship marked the formal opening of the USTA’s new grandstand stadium at Flushing Meadow’s USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. In partnership with Walters Group, SPS won the contract with AECOM Hunt to supply and install bleachers for the 5,800 seat grandstand. -

Planning Statement Glenmore Farm, Westbury

Planning Statement Glenmore Farm, Westbury July 2015 Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. The Proposal 3 3. The Site and Context 5 4. Planning Policy Context 6 5. Planning Assessment 12 6. Planning Obligations – Draft Heads of Terms 24 7. Summary and Conclusions 26 Contact Andrew Ross [email protected] Client Taylor Wimpey LPA Reference Wiltshire Council July 2015 1. Introduction 1.1 This Planning Statement has been prepared by Turley to accompany an outline application for planning permission submitted by Taylor Wimpey for up to 145 dwellings at Glenmore Farm, Westbury. 1.2 In addition to this Planning Statement the following documents also accompany the application and provide the information necessary to describe, assess and determine the proposals. • Site Location (Red Line) Plan – Ref. TAYA2036_1001B; • Buildings to be Demolished Plan – Ref. TAYA2036_4401; • Access Plan – Ref.27325-002-006A; • Illustrative Masterplan – Ref. TAYA2036_3207B; • Land Areas Plan – Ref. TAYA2036_3602; • Design and Access Statement; • Planning Statement - including Draft Heads of Terms; • Topographical Survey; • Statement of Community Involvement; • Transport Assessment; • Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment; • Ecological Impact Assessment Report; • Ecological Mitigation and Enhancement Strategy; • Flood Risk Assessment; • Utility Infrastructure Site Appraisal; • Phase 1 Ground Condition Assessment; • Tree Survey; • Noise Assessment Report; • Historic Environment – Desk Based Assessment; • Historic Environment – Gradiometer Survey Report; • Agricultural Land Classification Report; 1 • Additional CIL questions; 1.3 This Planning Statement is structured as follows: • Description of the proposal (Section 2); • Description of the Site and Context (Section 3); • A summary of the Planning Policy Context (Section 4); • Planning Assessment (Section 5); • A summary of Section 106 Agreement Heads of Terms (Section 6); and • Summary and Conclusions (Section 7). -

Anticipated Acquisition by Persimmon Plc of Westbury Plc

Anticipated acquisition by Persimmon plc of Westbury plc The OFT's decision on reference under section 33(1) given on 23 December 2005. Full text of decision published on 16 January 2006. PARTIES 1. Persimmon plc (Persimmon) is one of the UK's largest house building groups. It currently operates around 400 developments across Great Britain, each of which is managed from one of 33 regional offices. 2. Westbury plc (Westbury), headquartered in Cheltenham, is also a house building group comprising nine regionally based operations and a manufacturing plant. Westbury's UK turnover in its last financial year was £893 million. TRANSACTION 3. Persimmon is proposing the acquisition of the entire issued and to be issued share capital of Westbury by means of a cash offer. It notified this anticipated transaction to the OFT as a formal merger notice on 24 November 2005. The extended statutory deadline is 10 January 2006. JURISDICTION 4. As a result of this transaction Persimmon and Westbury will cease to be distinct. Westbury's UK turnover exceeds £70 million, consequently the turnover test in section 23(1)(b) of the Enterprise Act 2002 (the Act) is satisfied. The OFT therefore believes that it is or may be the case that arrangements are in progress or in contemplation which, if carried into effect, will result in the creation of a relevant merger situation. 1 RELEVANT MARKET Product scope 5. The parties are both commercially active in the construction of new housing. 6. The available evidence suggests that, on the demand side, new housing and older housing exert reciprocal competitive price constraint. -

Focusing on Our Customers

Focusing on our customers Annual Report 2019 What’s inside Highlights this report? Strategic report Financial Non-Financial 2 Chairman’s statement 8 Who we are 3 10 The UK housing market Revenue -2% HBF Score +6% 12 Our business model 14 Our strategic objectives £3.65bn 83.7% 16 Our Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) 2018: £3.74bn 2018: 78.9% 19 A sustainable business 22 Group Chief Executive’s statement 1 28 Financial review Operating margin -3% Charitable foundation donations 32 Strategic update 57 How we manage risk 28.2% £2.3m 58 Our principal risks 2018: 29.0% 2018: £1.3m 64 Viability statement 66 Section 172 Statement 4 71 Non-Financial Information Profit before tax -5% Affordable homes +8% Governance £1,040.8m 3,589 Directors’ Report: 2018: £1,090.8m 2018: 3,333 72 Chairman’s introduction to Corporate Governance 74 Board leadership Net assets per share +2% Trainees and apprentices +19% 76 Corporate Governance Statement 84 Nomination Committee Report 1,021.7p c.750 87 Chair’s introduction to the Audit Committee Report 2018: 1,006.0p 2018: c.630 89 Audit Committee Report 95 Other disclosures Cash generation Investment in local Remuneration: pre land investment2 -8% communities5 +10% 98 Remuneration Committee Chair’s Statement 101 Directors’ future Remuneration Policy £996.2m £522m 110 Annual Report on Remuneration 2018: £1,082.8m 2018: £474m Financial statements Homes provided 121 Statement Of Directors’ Responsibilities Dividend with FibreNest +704% 122 Independent Auditor’s Report 129 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 235p 4,679 130 Balance Sheets 2018: 235p 2018: 582 131 Statement of Changes in Shareholders’ Equity 133 Cash Flow Statements 134 Notes to the Financial Statements Other information 1 Stated on revenue of £3,649.4m (2018: £3,737.6m) and profit from operations of £1,029.4m (2018: £1,082.7m). -

Old Westbury Funds

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-Q Quarterly schedule of portfolio holdings of registered management investment company filed on Form N-Q Filing Date: 2012-03-27 | Period of Report: 2012-01-31 SEC Accession No. 0000930413-12-001798 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER OLD WESTBURY FUNDS INC Mailing Address Business Address 760 MOORE ROAD 760 MOORE ROAD CIK:909994| IRS No.: 232874698 | State of Incorp.:MD | Fiscal Year End: 1031 KING OF PRUSSIA PA 19406 KING OF PRUSSIA PA 19406 Type: N-Q | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-07912 | Film No.: 12715936 3027914394 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-Q QUARTERLY SCHEDULE OF PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number 811-07912 Old Westbury Funds, Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 760 Moore Rd. King of Prussia, PA 19406 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Andrew J. McNally BNY Mellon Investment Servicing (US) Inc. 760 Moore Rd. King of Prussia, PA 19406 (Name and address of agent for service) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: 800-607-2200 Date of fiscal year end: October 31 Date of reporting period: January 31, 2012 Form N-Q is to be used by management investment companies, other than small business investment companies registered on Form N-5 (§§ 239.24 and 274.5 of this chapter), to file reports with the Commission, not later than 60 days after the close of the first and third fiscal quarters, pursuant to rule 30b1-5 under the Investment Company Act of 1940 (17 CFR 270.30b1-5). -

Annual Report & Accounts 2009

www.bellway.co.uk Annual Report & Accounts 2009 Bellway p.l.c. ReportAnnual Accounts 2009 & p.l.c. Bellway Seaton Burn House, Dudley Lane, Seaton Burn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE13 6BE Tel: (0191) 217 0717 Fax: (0191) 236 6230 DX: 711760 Seaton Burn www.bellway.co.uk Bellway p.l.c. Annual Report & Accounts 2009 Introduction Since its formation more Bellway p.l.c. Seaton Burn House, Dudley Lane, Seaton Burn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE13 6BE than 50 years ago, Bellway Tel: (0191) 217 0717; Fax: (0191) 236 6230; DX: 711760 Seaton Burn; Website: www.bellway.co.uk Bellway Homes Limited has built over 100,000 NORTHERN REGION SOUTHERN REGION East Midlands Essex Wessex No. 3 Romulus Court Bellway House Bellway House homes. It is recognised Meridian East 1 Rainsford Road Embankment Way Meridian Business Park Chelmsford Castleman Business Centre Braunstone Town Essex CM1 2PZ Ringwood throughout the industry Leicester LE19 1YG Tel: (01245) 259 989 Hampshire BH24 1EU Tel: (0116) 282 0400 Fax: (01245) 259 996 Tel: (01425) 477 666 Fax: (0116) 282 0401 DX: 121935 Chelmsford 6 Fax: (01425) 476 774 for building quality homes. DX: 45710 Ringwood North East North London Peel House Bellway House OTHER SUBSIDIARY Main Street, Ponteland Bury Street, Ruislip Newcastle upon Tyne Middlesex HA4 7SD Bellway Housing Trust Limited NE20 9NN Tel: (01895) 671 100 Seaton Burn House Contents Tel: (01661) 820 200 Fax: (01895) 671 111 Dudley Lane Business Review Fax: (01661) 821 010 Seaton Burn Financial Highlights 01 DX: 68924 Ponteland 2 Northern Home Counties Newcastle upon Tyne -

Affordable Housing – Supplementary Planning Document Consultation Draft

Affordable Housing – Supplementary Planning Document Consultation Draft Consultation statement The following details accompany the consultation on the draft Affordable Housing Supplementary Planning Document (SPD), as required by the Town and Country Planning (Local Development) (England) Regulations 2004 (Regulation 17). Pre production consultation When consultation 28 September 2006 took place What was Housing Needs Assessment results consulted upon Who was Those marked with an asterix at Appendix 1 consulted How was Seminar which outlined results of Housing Needs consultation Assessment and how the Council was going to undertaken address the affordable housing issue. Summary of the The seminar was an opportunity to share the findings main issues raised of the Housing Needs Assessment prior to undertaking a pre-production consultation When consultation Between 4 October 2006 and 15 November 2006 took place What was Pre-production consultation document consulted upon Who was See Appendix 1 consulted How was Letters and consultation document sent to those listed consultation at Appendix 1. In addition, the consultation document undertaken was placed on the District Council’s website. Summary of the A number of issues were raised which were main issues raised considered in preparing the draft Supplementary Planning Document. The comments received are summarised report at Appendix 2 APPENDIX 1 LIST OF PEOPLE CONSULTED Government Office for the East Midlands Leicestershire County Council All Parish Council in North West Leicestershire Home -

Participating Builders (PDF)

Builders with access to Higher LTV Newbuild Products. Builders with access to Higher LTV Newbuild Products. Group/brand Trading name A & J Stephen A & J Stephen A2 Dominion A2 Dominion / Fabrica Abbey New Homes Abbey New Homes / Abbey Developments Aitch Group Aitch / Mura Estates AJ & DL Cutler AJ & DL Cutler / Eden Properties Allanwater Homes Allanwater Homes Ama (New Town) Ltd Ama (New Town) Ltd Ambassador Homes Ambassador Homes / Ambassador Residential Antrim Construction Company Ltd Anwyl Homes Anwyl Homes Aquinna Homes Arncliffe Homes Ltd Artisan Artisan Ascent Homes Ascent Homes / Arch Development Projects Avant Avant / Gladedale Homes / Ben Bailey Homes / Bett Homes / Country & Metropolitan / Manor Kingdom Backhouse Backhouse Land Ltd / Backhouse (Calne) Ltd / Backhouse (Westbury) Jv Ltd / Backhouse (Castle Cary) Jv Ltd Bancon Homes Bancon Homes Bargate Homes Barnfield Construction Barnfield Construction Barratt Homes Barratt Homes / David Wilson Homes / Ward Homes Barwood Homes Barwood Homes Beal Homes Beal Homes Beech Developments (Nw) Ltd Bellway Homes Bellway Homes / Ashberry Homes Berkeley Homes Berkeley Homes / St James / St George / Berkeley First / St Edwards / St William Bloor Homes Bloor Homes Blueprint Blueprint 2 Group/brand Trading name Bovis Homes Bovis Homes Braidwater Ltd BW Homes & Construction Ltd Briar Homes Caedmon Homes Norstar Real Estate Ltd CALA Homes CALA Homes / Banner Homes Campbell Buchannan Cavanna Homes Ltd Cavanna Homes Ltd CCG Homes CCG Homes CG Fry & Son CG Fry & Son Chap Homes Chap Homes Chartford -

Taylor Wimpey Annual Report and Accounts 2020

Taylor Wimpey plc Annual Report and Accounts 2020 Emerging StrongerAnnual Report and Accounts 2020 www.taylorwimpey.co.uk Contents Taylor Wimpey plc is a customer-focused residential Strategic report developer building and delivering homes and 2 Chairman’s statement communities across the UK and in Spain. 4 Chief Executive’s statement 6 Our market environment 10 Our response in 2020 12 Our equity raise 14 Our management 16 Our robust investment case 18 Our purpose 20 Our business model Our purpose 22 Our strategy and key performance indicators 26 Materiality assessment 28 Our stakeholders 42 Environmental strategy Our response is to build great 44 Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures Our equity raise in 2020 46 Our approach to identifying and managing risk See pages 12 and 13 See pages 10 and 11 49 Principal Risks and uncertainties homes and 54 Group financial review Directors’ report: governance 60 Chairman’s Statement 62 Governance at a glance create thriving 80 Nomination and Governance Committee report 90 Audit Committee report 98 Remuneration Committee report communities. 121 Statutory, regulatory and other information Financial statements 124 Independent auditor’s report Emerging 130 Consolidated income statement stronger for our 131 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income Our purpose stakeholders This is what our teams come to work to do each 132 Consolidated balance sheet See pages 18 and 19 See pages 28 to 41 133 Consolidated statement of changes in equity and every day and is where the core drivers of 134 Consolidated cash flow statement value for all our stakeholders ultimately lie. 135 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 165 Company balance sheet 2020 has not been a normal year. -

Becoming a Customer-Centric Homebuilder

Taylor Wimpey plc Annual Report and Accounts 2018 Becoming a www.taylorwimpey.co.uk customer-centric homebuilder Annual Report and Accounts 2018 At a glance how we performed in 2018 Revenue (£m) Customer satisfaction 8-week score Tangible net asset Group completions including JVs Number recruited to early talent Operating profit* (£m) ‘Would you recommend?’ (%) value per share† (p) programmes in the year 2018 4,082.0 2018 15,275 2018 880.2 2017 3,965.2 90 98.3 2017 14,842 175 2017 844.1 2016 3,676.2 2016 14,185 2016 768.1 2017: 89 2017: 95.7 2017: 126 Return on net Annual Injury Incidence Rate (per Year end net cash‡ (£m) Profit for the year (£m) Basic earnings per share (p) Employee turnover (%) operating assets** (%) 100,000 employees and contractors) 14.5 644.1 33.4 656.6 20.1 228 2017: 511.8 2017: 555.3 2017: 17.0 2017: 14.0 2017: 32.5 2017: 152 Profit before tax (£m) Adjusted basic earnings Net private sales rate Total dividend per share (p) per share†† (p) per outlet per week Construction Quality Review Landbank years 2018 810.7 15.28 2017 682.0 21.3 0.80 3.93 c.5.1 2017: 13.79 2016 732.9 2017: 20.2 2017: 0.77 2017: 3.74 2017: c.5.1 Definitions can be found in the Group financial review on page 53 North Division Central and South We participate in various benchmarks and have West Division been awarded a number of industry accreditations Where we 6,431 Homes completed 5,259 operate 10 offices Homes completed 8 offices London and South We operate at a local level UK map key East Division Spain from 24 regional businesses Head office across the UK, and we also Regional offices 3,132 342 have operations in Spain. -

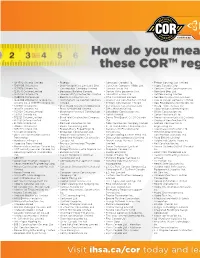

How Do You Measure up Against COR™ Registered Firms

How do you measure up against these CORTM registered firms? • 1014542 Ontario Limited • Bigelow • Comstock Canada Ltd. • Frecon Construction Limited • 1099708 Ontario Inc • Bird Management Limited & Bird • Con-Drain Company (1983) Ltd. • Fugro Canada Corp • 1103458 Ontario Inc. Construction Company Limited • Connco Group Ltd • Garrison Creek Construction Inc. • 1231576 Ontario Limited • Bouygues Building Canada • Contro Valve Equipment Inc. • Garritano Bros Ltd. • 1320376 Ontario Ltd. • Beacon Utility Contractors Limited • Covertite Eastern Ltd. • Gazzola Paving Limited • 1428508 Ontario Ltd. • Berkim Construction Inc • CRA Contractors Limited • Gen-Eer Construction Limited • 1434368 Ontario Inc. & 1434373 • Bermingham Foundation Solutions • Cruickshank Construction Limited • Geo. A. Kelson Company Limited Ontario Inc. & 1434374 Ontario Inc Limited • D Grant Construction Limited • Geo-Foundations Contractors Inc. • 1510610 Ontario Inc. • Best Guard Security Incorporated • D.J. Venasse Construction Limi • George Stone & Sons Inc. • 1610259 Ontario Ltd. • Black & Mcdonald Limited • D.M.C Mechanical Ltd. • Gibbs Wilson Contracting Inc. • 1721424 Ontario Limited • Blackstone Paving & Construction • Dalla Bona Construction Inc. • Giffels Constructors Inc • 2331131 Ontario Inc. Limited • Dalren Limited • Gorlan Mechanical Ltd. • 352021 Ontario Limited • Bondfield Construction Company • Davey Tree Expert Co. Of Canada • Grace Instrumentation & Controls • 451231 Ontario Limited Limited Ltd. • Graebeck Construction Ltd • 614128 Ontario Ltd. •