Statements (Admissions, Confessions)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Tribunals and Rules of Evidence: the Case for Respecting and Preserving the "Priest-Penitent" Privilege Under International Law

American University International Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 3 Article 3 2000 International Tribunals and Rules of Evidence: The Case for Respecting and Preserving the "Priest- Penitent" Privilege Under International Law Robert John Araujo S.J. Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Araujo, S.J., Robert John. "International Tribunals and Rules of Evidence: The asC e for Respecting and Preserving the "Priest-Penitent" Privilege Under International Law." American University International Law Review 15, no. 3 (2000): 639-666. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERNATIONAL TRIBUNALS AND RULES OF EVIDENCE: THE CASE FOR RESPECTING AND PRESERVING THE "PRIEST-PENITENT" PRIVILEGE UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW ROBERT JOHN ARAUJO, S.J." INTRODUCTION .............................................. 640 I. THE PRIEST-PENITENT PRIVILEGE'S ORIGINS ........ 643 II. THE PRIVILEGE AT CIVIL AND COMMON LAW ....... 648 A. EUROPE, CANADA, AUSTRALIA, AND NEW ZEALAND ....... 648 B. THE UNITED STATES ...................................... 657 Ed. THE PRIVILEGE UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW ....... 661 CONCLU SION ................................................. 665 The Lord spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the Israelites-When a man or woman wrongs another, breaking faith with the Lord, that person in- curs guilt and shall confess the sin that has been committed. The person shall make full restitution for the wrong, adding one fifth to it, and giving it to the one who was wronged!' If we confess our sins, he who is faithful and just will forgive us our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness. -

Cops Or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 5 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dimitri Epstein, Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epstein: Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute App COPS OR ROBBERS? HOW GEORGIA'S DEFENSE OF HABITATION STATUTE APPLIES TO NONO- KNOCK RAIDS BY POLICE Dimitri Epstein*Epstein * INTRODUCTION Late in the fall of 2006, the city of Atlanta exploded in outrage when Kathryn Johnston, a ninety-two-year old woman, died in a shoot-out with a police narcotics team.team.' 1 The police used a "no"no- knock" search warrant to break into Johnston's home unannounced.22 Unfortunately for everyone involved, Ms. Johnston kept an old revolver for self defense-not a bad strategy in a neighborhood with a thriving drug trade and where another elderly woman was recently raped.33 Probably thinking she was being robbed, Johnston managed to fire once before the police overwhelmed her with a "volley of thirty-nine" shots, five or six of which proved fatal.fata1.44 The raid and its aftermath appalled the nation, especially when a federal investigation exposed the lies and corruption leading to the incident. -

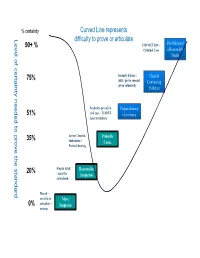

Level of Certainty Needed to Prove the Standard

% certainty Curved Line represents Level of certainty needed to prove the standard needed toprove of certainty Level difficulty to prove or articulate 90+ % CONVICTION – Proof Beyond Criminal Case a Reasonable Doubt 75% Insanity defense / Clear & alibi / prove consent Convincing given voluntarily Evidence Needed to prevail in Preponderance 51% civil case – LIABLE of evidence Asset Forfeiture 35% Arrest / Search / Probable Indictment / Cause Pretrial hearing 20% Stop & Frisk Reasonable – must be Suspicion articulated Hunch – not able to Mere 0% articulate / Suspicion no stop Mere Suspicion – This term is used by the courts to refer to a hunch or intuition. We all experience this in everyday life but it is NOT enough “legally” to act on. It does not mean than an officer cannot observe the activity or person further without making contact. Mere suspicion cannot be articulated using any reasonably accepted facts or experiences. An officer may always make a consensual contact with a citizen without any justification. The officer will however have not justification to stop or hold a person under this situation. One might say something like, “There is just something about him that I don’t trust”. “I can’t quit put my finger on what it is about her.” “He looks out of place.” Reasonable Suspicion – Stop, Frisk for Weapons, *(New) Search of vehicle incident to arrest under Arizona V. Gant. The landmark case for reasonable suspicion is Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) This level of proof is the justification police officers use to stop a person under suspicious circumstances (e.g. a person peaking in a car window at 2:00am). -

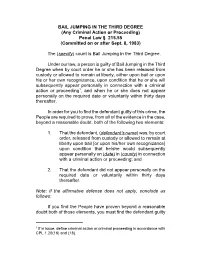

BAIL JUMPING in the THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action Or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on Or After Sept

BAIL JUMPING IN THE THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on or after Sept. 8, 1983) The (specify) count is Bail Jumping in the Third Degree. Under our law, a person is guilty of Bail Jumping in the Third Degree when by court order he or she has been released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty, either upon bail or upon his or her own recognizance, upon condition that he or she will subsequently appear personally in connection with a criminal action or proceeding1, and when he or she does not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. In order for you to find the defendant guilty of this crime, the People are required to prove, from all of the evidence in the case, beyond a reasonable doubt, both of the following two elements: 1. That the defendant, (defendant’s name) was, by court order, released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty upon bail [or upon his/her own recognizance] upon condition that he/she would subsequently appear personally on (date) in (county) in connection with a criminal action or proceeding; and 2. That the defendant did not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. Note: If the affirmative defense does not apply, conclude as follows: If you find the People have proven beyond a reasonable doubt both of those elements, you must find the defendant guilty 1 If in issue, define criminal action or criminal proceeding in accordance with CPL 1.20(16) and (18). -

Confessions of Third Persons in Criminal Cases L

Cornell Law Review Volume 1 Article 3 Issue 2 January 1916 Confessions of Third Persons in Criminal Cases L. A. Wilder Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation L. A. Wilder, Confessions of Third Persons in Criminal Cases, 1 Cornell L. Rev. 82 (1916) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol1/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF THIRD PERSONS IN CRIMINAL CASES By L. A. WILDER1 Why should a confession of a specific crime, which would be admis- sible against the confessor if he were on trial, be inadmissible in favor of a third person charged with the offense, when the confessor is not available as a witness? No doubt the average layman would declare this state of the law glaringly inconsistent in itself, and wholly incompatible with the professed attitude of criminal courts toward accused persons. And while the general sense of justice in the abstract is not always a true test of justice in the concrete, the fact that it is shocked by the denial to A of the benefit of B's confession, however voluntary and reliable it may be, is sufficient to justify a comment upon the rule which so excludes the confession. Of course, it is understood that the confession (as distinguished from an admission) is admitted in evidence against the confessor by virtue of that exception to the hearsay rule, which lets in declara- tions against the interest of the declarant. -

Questions and Answers

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 34 | Issue 1 Article 8 1943 Questions and Answers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Questions and Answers, 34 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 43 (1943-1944) This Correspondence is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Questions and Answers David Geeting Monroe (Ed.) Long before the science of criminal investigation came into repute, enforcement officials had come to rely upon the confession as an important means of establishing guilt. The courts, for example, viewed confessions as one of the best and most substantial species of evidence. They assumed, and correctly, that no person in the full possession of his faculties would voluntarily' sacrifice life, liberty, or property by confessing to a crime he did not commit. And from the point of view of the police, the confession offered an invaluable means of disclosing guilt in light of the exceptional difficulties involved in fixing criminality. For crimes in large part are cloaked in secrecy and men conscious of criminal purpose seek to shelter their knavery from the observing eyes of others. Thus, through the ages, the confession has held a significant position in the field of crime repression. Nevertheless, use of confessional evidence has suffered an harrassed and checkered career and on innumerable occasions has obstructed the normal functioning of enforcement. -

Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial

William & Mary Law Review Volume 37 (1995-1996) Issue 1 Article 10 October 1995 Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial Alan L. Adlestein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Alan L. Adlestein, Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial, 37 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 199 (1995), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol37/iss1/10 Copyright c 1995 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr CONFLICT OF THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS WITH LESSER OFFENSES AT TRIAL ALAN L. ADLESTEIN I. INTRODUCTION ............................... 200 II. THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS AND LESSER OFFENSES-DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONFLICT ........ 206 A. Prelude: The Problem of JurisdictionalLabels ..... 206 B. The JurisdictionalLabel and the CriminalStatute of Limitations ................ 207 C. The JurisdictionalLabel and the Lesser Offense .... 209 D. Challenges to the Jurisdictional Label-In re Winship, Keeble v. United States, and United States v. Wild ..................... 211 E. Lesser Offenses and the Supreme Court's Capital Cases- Beck v. Alabama, Spaziano v. Florida, and Schad v. Arizona ........................... 217 1. Beck v. Alabama-LegislativePreclusion of Lesser Offenses ................................ 217 2. Spaziano v. Florida-Does the Due Process Clause Require Waivability? ....................... 222 3. Schad v. Arizona-The Single Non-Capital Option ....................... 228 F. The Conflict Illustrated in the Federal Circuits and the States ....................... 230 1. The Conflict in the Federal Circuits ........... 232 2. The Conflict in the States .................. 234 III. -

Reasonable Cause Exists When the Public Servant Has

ESCAPE IN THE SECOND DEGREE Penal Law § 205.10(2) (Escape from Custody by Defendant Arrested for, Charged with, or Convicted of Felony) (Committed on or after September 8, 1983) The (specify) count is Escape in the Second Degree. Under our law, a person is guilty of escape in the second degree when, having been arrested for [or charged with] [or convicted of] a class C [or class D] [or class E] felony, he or she escapes from custody. The following terms used in that definition have a special meaning: CUSTODY means restraint by a public servant pursuant to an authorized arrest or an order of a court.1 "Public Servant" means any public officer or employee of the state or of any political subdivision thereof or of any governmental instrumentality within the state, [or any person exercising the functions of any such public officer or employee].2 [Add where appropriate: An arrest is authorized when the public servant making the arrest has reasonable cause to believe that the person being arrested has committed a crime. 3 Reasonable cause does not require proof that the crime was in fact committed. Reasonable cause exists when the public servant has 1 Penal Law §205.00(2). 2 Penal Law §10.00(15). 3 This portion of the charge assumes an arrest for a crime only as authorized by the provisions of CPL 140.10(1)(b). If the arrest was authorized pursuant to some other subdivision of CPL 140.10 or other law, substitute the applicable provision of law. knowledge of facts and circumstances sufficient to support a reasonable belief that a crime has been or is being committed.4 ] ESCAPE means to get away, break away, get free or get clear, with the conscious purpose to evade custody.5 (Specify the felony for which the defendant was arrested, charged or convicted) is a class C [or class D] [or class E] felony. -

Burden of Proof and 4Th Amendment

Burden of Proof and 4 th Amendment Burden of Proof Standards • Reasonable suspicion • Probable cause • Reasonable doubt Burden of proof • In the United States we enjoy a ‘presumption of innocence’. What does this mean? • This means, essentially, that you are innocent until proven guilty. But how do we prove guilt? • Law enforcement officers must have some basis for stopping or detaining an individual. • In order for an officer to stop and detain someone they must meet a standard of proof Reasonable Suspicion • Lowest standard • A belief or suspicion that • Officers cannot deprive a citizen of liberty unless the officer can point to specific facts and circumstances and inferences therefrom that would amount to a reasonable suspicion Probable Cause • More likely than not or probably true. • Probable cause- a reasonable amount of suspicion, supported by circumstances sufficiently strong to justify a prudent and cautious person’s belief that certain facts are probably true. • In other terms this could be understood as more likely than not of 51% likely. • This is the standard required to arrest someone and obtain a warrant. Reasonable Doubt • Beyond a reasonable doubt- This means that the notion being presented by the prosecution must be proven to the extent that there could be no "reasonable doubt" in the mind of a “reasonable person” that the defendant is guilty. There can still be a doubt, but only to the extent that it would not affect a reasonable person's belief regarding whether or not the defendant is guilty. 4th Amendment • Search -

MONOPOLY in LAW and ECONOMICS by EDWARD S

MONOPOLY IN LAW AND ECONOMICS By EDWARD S. MASON t I. THE TERM monopoly as used in the law is not a tool of analysis but a standard of evaluation. Not all trusts are held monopolistic but only "bad" trusts; not all restraints of trade are to be condemned but only "unreasonable" restraints. The law of monopoly has therefore been directed toward a development of public policy with respect to certain business practices. This policy has required, first, a distinction between the situations and practices which are to be approved as in the public interest and those which are to be disapproved, second, a classification of these situations as either competitive and consequently in the public interest or monopolistic and, if unregulated, contrary to the public in- terest, and, third, the devising and application of tests capable of demar- cating the approved from the disapproved practices. But the devising of tests to distinguish monopoly from competition cannot be completely separated from the formulation of the concepts. It may be shown, on the contrary, that the difficulties of formulating tests of monopoly have defi- nitely shaped the legal conception of monopoly. Economics, on the other hand, has not quite decided whether its task is one of description and analysis or of evaluation and prescription, or both. With respect to the monopoly problem it is not altogether clear whether the work of economists should be oriented toward the formu- lation of public policy or toward the analysis of market situations. The trend, however, is definitely towards the latter. The further economics goes in this direction, the greater becomes the difference between legal and economic conceptions of the monopoly problem. -

Cross Examining Police in False Confession Cases By: Attorney Deja Vishny*

The WISCONSIN Winter/Spring 2008 DEFENDER Volume 16, Issue 1 Cross Examining Police in False Confession Cases By: Attorney Deja Vishny* Many criminal defense lawyers are filled with dread at the idea of trying a confession case. We think the jury will never accept that people give false confessions. We worry that jurors and courts will always believe that because our clients gave a recorded confession, they must have committed the crime. Our experience in motion litigation has taught us that judges rarely, if ever, take the risk of suppressing the confession particularly when a crime is horrifying and highly publicized. Since the advent of mandatory recorded interrogation in juvenile and felony cases we have been lucky enough to be able to listen to the recording and pinpoint exactly how law enforcement agents are able to get our clients to confess. No longer is the process of getting a confession shrouded in mystery as the police enter into a closed off locked room with a suspect who is determined to maintain their innocence and emerge hours (sometimes days) later with a signed statement that proclaims “I did it”. However, defense lawyers listening to the tapes must be able to appreciate the significance of what is being said to cajole a confession. The lawyer handling a recorded interrogation case should always listen carefully to the recording of the entire interrogation as early as possible in the case. There have been many occasions of discrepancies between how a police officer will characterize the confession in testimony or a written report from how the statement was actually developed and what the tape shows the client’s actual words were. -

Classes of Misdemeanors: Anatomy of a Criminal Case

The Misdemeanor Process "It shall be the primary duty of all prosecuting attorneys...not to convict, but to see that justice is done." Art. 2.01 Texas Code of Criminal Procedure The County Attorney handles over XXXXXXX new misdemeanor cases each year. These crimes contribute to the steady erosion of our community's civility, order, and safety. These crimes, if undeterred, can and will erode the quality of life for all of the citizens of Ector County. As Ector County grows, its citizens must remain vigilant to lower the number of these quality of life crimes. The County Attorney thanks all those citizens who contribute to public safety through jury service, volunteer organizations, and reports of crime to law enforcement. Classes of Misdemeanors: This Office is responsible for the prosecution of all misdemeanor cases that are filed in Ector County. “Misdemeanor” is defined in the law as any crime where the maximum possible jail time is one year or less. There are three categories of misdemeanors: Class A; Class B; and Class C. Class A misdemeanors are punishable by a fine of up to $4,000 and/or confinement in jail of up to one year. Some examples of Class A misdemeanor offenses include assault causing bodily injury, driving while intoxicated second offense, theft of property valued at $500 to $1500, and resisting arrest. Class B misdemeanors are punishable by a fine of up to $2,000 and/or confinement in jail of up to six months. Some examples of Class B misdemeanor offenses include driving while intoxicated first offense, possession of marijuana less than two ounces, and telephone harassment.