Legislative Reform, Tenure, and Natural Resource Management in Niger: the New Rural Code

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress Report on Soil Fertility Restoration

PROGRESS REPORT ON SOIL FERTILITY RESTORATION PROJECT (WEST AFRICA) THE U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT BY INTERNATIONAL FERTILIZER DEVELOPMENT CENTER November, 1988 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pagie 1.0 Introduction 3 2.0 Start-up Phase and Staffing 7 2.1 Administration and Personnel Recruitment 7 2.2 Links with Organizations Promoting Fertilizer Use 8 2.3 National Collaborating Institutions and Zones of Operation 9 2.4 Preparation and Adoption of Supplementary Technical Paper 10 3.0 Development of Work Plan 11 4.0 Prel-minz.ry/Exploratory Survey 11 4.1 Ghana 12 4.2 Niger 13 4.3 Togo 15 5.0 Verification Survey and The Role of Women in the SFRP 15 6.0 On Farm Trials 16 6.1 Training of Collaborators in Ghana 16 6.2 Design and Establishment of OFT in Ghana 17 6.3 Design and Fstablishment of OFT in Niger 18 7.0 Environmental impact of Fertilizer Use 18 8.0 Operating Problems During Phase One 19 9.0 Project Monitoring/Management to Overcome Problems 19 10.0 Plans for 1988/89 20 11.0 Appendices 22 SFRP ;RC";ESS REPCRT 3 PROGRESS REPORT SOIL FERTILITY RESTORATIOV PROJECT (WEST AFRICA) 1.0 Introduction Rapidly increasing populations coupled with declining per capita food production continue to place sub-Saharan Africa at the center of international concern in relauion to food availability and production. The regions of best and Central Africa present some of the most complex problems in agricultural development during the latter quarter of this century. The soils of West Africa are generally low in fertility, very fragile, readily exhausted through Lropping, and prone to leaching of nutrients and erosion. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

Niger Country Brief: Property Rights and Land Markets

NIGER COUNTRY BRIEF: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS Yazon Gnoumou Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison with Peter C. Bloch Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison Under Subcontract to Development Alternatives, Inc. Financed by U.S. Agency for International Development, BASIS IQC LAG-I-00-98-0026-0 March 2003 Niger i Brief Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Purpose of the country brief 1 1.2 Contents of the document 1 2. PROFILE OF NIGER AND ITS AGRICULTURE SECTOR AND AGRARIAN STRUCTURE 2 2.1 General background of the country 2 2.2 General background of the economy and agriculture 2 2.3 Land tenure background 3 2.4 Land conflicts and resolution mechanisms 3 3. EVIDENCE OF LAND MARKETS IN NIGER 5 4. INTERVENTIONS ON PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS 7 4.1 The colonial regime 7 4.2 The Hamani Diori regime 7 4.3 The Kountché regime 8 4.4 The Rural Code 9 4.5 Problems facing the Rural Code 10 4.6 The Land Commissions 10 5. ASSESSMENT OF INTERVENTIONS ON PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKET DEVELOPMENT 11 6. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 13 BIBLIOGRAPHY 15 APPENDIX I. SELECTED INDICATORS 25 Niger ii Brief NIGER COUNTRY BRIEF: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS Yazon Gnoumou with Peter C. Bloch 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE COUNTRY BRIEF The purpose of the country brief is to determine to which extent USAID’s programs to improve land markets and property rights have contributed to secure tenure and lower transactions costs in developing countries and countries in transition, thereby helping to achieve economic growth and sustainable development. -

Caught in the Middle a Human Rights and Peace-Building Approach to Migration Governance in the Sahel

Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar CRU Report Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin CRU Report December 2018 December 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: © Jérôme Tubiana. Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the authors Fransje Molenaar is a Senior Research Fellow with Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit, where she heads the Sahel/Libya research programme. She specializes in the political economy of (post-) conflict countries, organized crime and its effect on politics and stability. -

Threat Analysis

Threat analysis: West African giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis peralta) in Republic of Niger April 2020 Kateřina Gašparová1, Julian Fennessy2, Thomas Rabeil3 & Karolína Brandlová1 1Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Kamýcká 129, 165 00 Praha Suchdol, Czech Republic 2Giraffe Conservation Foundation, Windhoek, Namibia 3Wild Africa Conservation, Niamey, Niger Acknowledgements We would like to thank the Nigerien Wildlife Authorities for their valuable support and for the permission to undertake the work. Particularly, we would like to thank the wildlife authorities’ members and rangers. Importantly, we would like to thank IUCN-SOS and European Commission, Born Free Foundation, Ivan Carter Wildlife Conservation Alliance, Sahara Conservation Fund, Rufford Small Grant, Czech University of Life Sciences and GCF for their valuable financial support to the programme. Overview The Sudanian savannah currently suffers increasing pressure connected with growing human population in sub-Saharan Africa. Human settlements and agricultural lands have negatively influenced the availability of resources for wild ungulates, especially with increased competition from growing numbers of livestock and local human exploitation. Subsequently, and in context of giraffe (Giraffa spp.), this has led to a significant decrease in population numbers and range across the region. Remaining giraffe populations are predominantly conserved in formal protected areas, many of which are still in the process of being restored and conservation management improving. The last population of West African giraffe (G. camelopardalis peralta), a subspecies of the Northern giraffe (G. camelopardalis) is only found in the Republic of Niger, predominantly in the central region of plateaus and Kouré and North Dallol Bosso, about 60 km south east of the capital – Niamey, extending into Doutchi, Loga, Gaya, Fandou and Ouallam areas (see Figure 1). -

Ifrc.Org; Phone +221.869.36.41; Fax +221

NIGER: HARSH WEATHER No. MDRNE001 08 February 2006 IN BILMA The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in over 183 countries. In Brief This DREF Bulletin is being issued based on the situation described below reflecting the information available at this time. CHF 48,000 (USD 38,400 or EUR 29,629) has been allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to respond to the needs in this operation. This operation is expected to be implemented over 3 months, and will be completed by 1 May 2007. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. <Click here to go directly to the attached map> This operation is aligned with the International Federation's Global Agenda, which sets out four broad goals to meet the Federation's mission to "improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity". Global Agenda Goals: · Reduce the numbers of deaths, injuries and impact from disasters. · Reduce the number of deaths, illnesses and impact from diseases and public health emergencies. · Increase local community, civil society and Red Cross Red Crescent capacity to address the most urgent situations of vulnerability. · Reduce intolerance, discrimination and social exclusion and promote respect for diversity and human dignity. The Situation In August 2006, Bilma – located in the Agadez Region, about 1,600 km from Eastern Niamey, Niger – experienced flooding, following what was reported to be the highest rainfall recorded in the area since 1923. -

Preliminary Satellite Derived Flood Assessment in Niamey, Maradi & Agadez Regions, Niger

Preliminary satellite derived flood assessment in Niamey, Maradi & Agadez Regions, Niger Production Date: 09 Sep 2019 Areas of Interest (AOIs) AOI 3 NIGER Agadez Agadaz Tahoua Diffa Zinder Tillaberi Maradi Doso AOI 1 AOI 2 Niamey Maradi 2 AOI 1 : Niamey Region, Niger Sentinel-2 false color composite Pre-flood situation acquired on 17 AugIGERNIGER 2019 NIGER SUDAN Airport 3 km 3 Source: EO-browser sentinel-hub AOI 1 : Niamey Region, Niger Sentinel-2 false color composite acquired on 06 Sep 2019 NIGER NIGER SUDAN flooded areas close to urban zone Goroual Airport Inundated agricultural fields in the vicinity of urban areas Wet area in Agricultural zone Flooded areas close to urban zone and several agricultural fields along the river seem to be flooded 3 km 4 Source: EO-browser sentinel-hub AOI 2 : Maradi Region, Niger Sentinel-2 false color composite Sentinel-2 false color composite acquired on 31 Aug 2019 acquired on 05 Sep 2019 1 km 1 km Zone with receded waters north of Maradi The Airport The Airport NIGER Agricultural areas Receding waters in Maradi area between 31 Aug 2019 and 05 Sep 2019 5 Source: EO-browser sentinel-hub AOI 2 : Maradi Region, Niger Sentinel-1 Radar Image acquired on 05 Sep 2019 No fluvial overbank flow observed NIGER SUDAN 1 km 6 Source: EO-browser sentinel-hub AOI 3 : Agadez Region, Niger GeoEye-1 acquired on 04 Aug 2019 Worldview-3 acquired on 04 Sep 2019 3 km 3 km Agricultural Agricultural areas areas Agadez Agadez Airport Airport NIGER Situation assessment in Agadez as of 04 Sep 2019 7 Copyright ©: 2019 DigitalGlobe Source: US Department of State – HIU – NextView License AOI 3 : Agadez Region, Niger Worldview-3 acquired on 04 Sep 2019: Post-flood situation Waters have receded from several zones of Agadez (e.g. -

F:\Niger En Chiffres 2014 Draft

Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 1 Novembre 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Direction Générale de l’Institut National de la Statistique 182, Rue de la Sirba, BP 13416, Niamey – Niger, Tél. : +227 20 72 35 60 Fax : +227 20 72 21 74, NIF : 9617/R, http://www.ins.ne, e-mail : [email protected] 2 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Pays : Niger Capitale : Niamey Date de proclamation - de la République 18 décembre 1958 - de l’Indépendance 3 août 1960 Population* (en 2013) : 17.807.117 d’habitants Superficie : 1 267 000 km² Monnaie : Francs CFA (1 euro = 655,957 FCFA) Religion : 99% Musulmans, 1% Autres * Estimations à partir des données définitives du RGP/H 2012 3 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 4 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Ce document est l’une des publications annuelles de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Il a été préparé par : - Sani ALI, Chef de Service de la Coordination Statistique. Ont également participé à l’élaboration de cette publication, les structures et personnes suivantes de l’INS : les structures : - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Economiques (DSEE) ; - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Démographiques et Sociales (DSEDS). les personnes : - Idrissa ALICHINA KOURGUENI, Directeur Général de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Ibrahim SOUMAILA, Secrétaire Général P.I de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Ce document a été examiné et validé par les membres du Comité de Lecture de l’INS. Il s’agit de : - Adamou BOUZOU, Président du comité de lecture de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Djibo SAIDOU, membre du comité - Mahamadou CHEKARAOU, membre du comité - Tassiou ALMADJIR, membre du comité - Halissa HASSAN DAN AZOUMI, membre du comité - Issiak Balarabé MAHAMAN, membre du comité - Ibrahim ISSOUFOU ALI KIAFFI, membre du comité - Abdou MAINA, membre du comité. -

Niger Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals September 2017

NIGER STAPLE FOOD AND LIVESTOCK MARKET FUNDAMENTALS SEPTEMBER 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET NIGER Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals 2017 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Disclaimer This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Acknowledgements FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Niger who contributed their time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. Cover photos @ FEWS NET and Flickr Creative Commons. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii FEWS NET NIGER Staple Food and Livestock Market Fundamentals 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Arrêt N° 012/11/CCT/ME Du 1Er Avril 2011 LE CONSEIL

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 012/11/CCT/ME du 1er Avril 2011 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du premier avril deux mil onze tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la Constitution ; Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-096 du 28 décembre 2010 portant code électoral ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2011-121/PCSRD/MISD/AR du 23 février 2011 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le deuxième tour de l’élection présidentielle ; Vu l’arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 portant validation des candidatures aux élections présidentielles de 2011 ; Vu l’arrêt n° 006/11/CCT/ME du 22 février 2011 portant validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour du 31 janvier 2011 ; Vu la lettre n° 557/P/CENI du 17 mars 2011 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante transmettant les résultats globaux provisoires du scrutin présidentiel 2ème tour, aux fins de validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 028/PCCT du 17 mars 2011 de Madame le Président du Conseil constitutionnel portant -

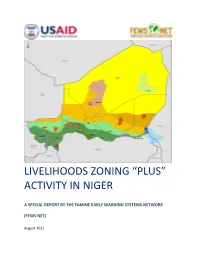

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

BROCHURE Dainformation SUR LA Décentralisation AU NIGER

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER MINISTERE DE L’INTERIEUR, DE LA SECURITE PUBLIQUE, DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES AFFAIRES COUTUMIERES ET RELIGIEUSES DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES COLLECTIVITES TERRITORIALES brochure d’INFORMATION SUR LA DÉCENTRALISATION AU NIGER Edition 2015 Imprimerie ALBARKA - Niamey-NIGER Tél. +227 20 72 33 17/38 - 105 - REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER MINISTERE DE L’INTERIEUR, DE LA SECURITE PUBLIQUE, DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES AFFAIRES COUTUMIERES ET RELIGIEUSES DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES COLLECTIVITES TERRITORIALES brochure d’INFORMATION SUR LA DÉCENTRALISATION AU NIGER Edition 2015 - 1 - - 2 - SOMMAIRE Liste des sigles .......................................................................................................... 4 Avant propos ............................................................................................................. 5 Première partie : Généralités sur la Décentralisation au Niger ......................................................... 7 Deuxième partie : Des élections municipales et régionales ............................................................. 21 Troisième partie : A la découverte de la Commune ......................................................................... 25 Quatrième partie : A la découverte de la Région .............................................................................. 53 Cinquième partie : Ressources et autonomie de gestion des collectivités ........................................ 65 Sixième partie : Stratégies et outils