The Palm Report Photo by Tim Mckernan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAXON:Rhopalostylis Baueri SCORE:-2.0 RATING:Low Risk

TAXON: Rhopalostylis baueri SCORE: -2.0 RATING: Low Risk Taxon: Rhopalostylis baueri Family: Arecaceae Common Name(s): Norfolk Island palm Synonym(s): Areca baueri Hook. f. ex Lem. Eora(basionym) baueri (H. Wendl. & Drude) O. F. RhopalostylisCook cheesemanii Becc. ex Cheeseman Assessor: No Assessor Status: Assessor Approved End Date: WRA Score: -2.0 Designation: L Rating: Low Risk Keywords: Subtropical Palm, Unarmed, Shade-tolerant, Thicket-forming, Bird-dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 n 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier -

Biosíntesi, Distribució, Acumulació I Funció De La Vitamina E En Llavors: Mecanismes De Control

Biosíntesi, distribució, acumulació i funció de la vitamina E en llavors: mecanismes de control Laura Siles Suárez Aquesta tesi doctoral està subjecta a la llicència Reconeixement- NoComercial – SenseObraDerivada 3.0. Espanya de Creative Commons. Esta tesis doctoral está sujeta a la licencia Reconocimiento - NoComercial – SinObraDerivada 3.0. España de Creative Commons. This doctoral thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0. Spain License. Barcelona, febrer de 2017 Biosíntesi, distribució, acumulació i funció de la vitamina E en llavors: mecanismes de control Memòria presentada per Laura Siles Suarez per a optar al grau de Doctora per la Universitat de Barcelona. Aquest treball s’emmarca dins el programa de doctorat de BIOLOGIA VEGETAL del Departament de Biologia Evolutiva, Ecologia i Ciències Ambientals (BEECA) de la Facultat de Biologia de la Universitat de Barcelona. El present treball ha estat realitzat al Departament de Biologia Evolutiva, Ecologia i Ciències Ambientals de la Facultat de Biologia (BEECA) de la Universitat de Barcelona sota la direcció de la Dra. Leonor Alegre Batlle i el Dr. Sergi Munné Bosch. Doctoranda: Directora i Codirector de Tesi: Tutora de Tesi: Laura Siles Suarez Dra. Leonor Alegre Batlle Dra. Leonor Alegre Batlle Dr. Sergi Munné Bosch “Mira profundamente en la naturaleza y entonces comprenderás todo mejor”- Albert Einstein. “La creación de mil bosques está en una bellota”-Ralph Waldo Emerson. A mi familia, por apoyarme siempre, y a mis bichejos peludos Índex ÍNDEX AGRAÏMENTS i ABREVIATURES v INTRODUCCIÓ GENERAL 1 Vitamina E 3 1.1.Descobriment i estudi 3 1.2.Estructura química i classes 3 Distribució de la vitamina E 5 Biosíntesi de vitamina E 6 3.1. -

Seed Geometry in the Arecaceae

horticulturae Review Seed Geometry in the Arecaceae Diego Gutiérrez del Pozo 1, José Javier Martín-Gómez 2 , Ángel Tocino 3 and Emilio Cervantes 2,* 1 Departamento de Conservación y Manejo de Vida Silvestre (CYMVIS), Universidad Estatal Amazónica (UEA), Carretera Tena a Puyo Km. 44, Napo EC-150950, Ecuador; [email protected] 2 IRNASA-CSIC, Cordel de Merinas 40, E-37008 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Matemáticas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Salamanca, Plaza de la Merced 1–4, 37008 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-923219606 Received: 31 August 2020; Accepted: 2 October 2020; Published: 7 October 2020 Abstract: Fruit and seed shape are important characteristics in taxonomy providing information on ecological, nutritional, and developmental aspects, but their application requires quantification. We propose a method for seed shape quantification based on the comparison of the bi-dimensional images of the seeds with geometric figures. J index is the percent of similarity of a seed image with a figure taken as a model. Models in shape quantification include geometrical figures (circle, ellipse, oval ::: ) and their derivatives, as well as other figures obtained as geometric representations of algebraic equations. The analysis is based on three sources: Published work, images available on the Internet, and seeds collected or stored in our collections. Some of the models here described are applied for the first time in seed morphology, like the superellipses, a group of bidimensional figures that represent well seed shape in species of the Calamoideae and Phoenix canariensis Hort. ex Chabaud. -

Mar2009sale Finalfinal.Pub

March SFPS Board of Directors 2009 2009 The Palm Report www.southfloridapalmsociety.com Tim McKernan President John Demott Vice President Featured Palm George Alvarez Treasurer Bill Olson Recording Secretary Lou Sguros Corresponding Secretary Jeff Chait Director Sandra Farwell Director Tim Blake Director Linda Talbott Director Claude Roatta Director Leonard Goldstein Director Jody Haynes Director Licuala ramsayi Palm and Cycad Sale The Palm Report - March 2009 March 14th & 15th This publication is produced by the South Florida Palm Society as Montgomery Botanical Center a service to it’s members. The statements and opinions expressed 12205 Old Cutler Road, Coral Gables, FL herein do not necessarily represent the views of the SFPS, it’s Free rare palm seedlings while supplies last Board of Directors or its editors. Likewise, the appearance of ad- vertisers does not constitute an endorsement of the products or Please visit us at... featured services. www.southfloridapalmsociety.com South Florida Palm Society Palm Florida South In This Issue Featured Palm Ask the Grower ………… 4 Licuala ramsayi Request for E-mail Addresses ………… 5 This large and beautiful Licuala will grow 45-50’ tall in habitat and makes its Membership Renewal ………… 6 home along the riverbanks and in the swamps of the rainforest of north Queen- sland, Australia. The slow-growing, water-loving Licuala ramsayi prefers heavy Featured Palm ………… 7 shade as a juvenile but will tolerate several hours of direct sun as it matures. It prefers a slightly acidic soil and will appreciate regular mulching and protection Upcoming Events ………… 8 from heavy winds. While being one of the more cold-tolerant licualas, it is still subtropical and should be protected from frost. -

Ptychosperma Macarthurii : 85 Discovery, Horticulture and Obituary 97 Taxonomy Advertisements 84, 102 J.L

Palms Journal of the International Palm Society Vol. 51(2) Jun. 2007 THE INTERNATIONAL PALM SOCIETY, INC. The International Palm Society Palms (formerly PRINCIPES) NEW • UPDATED • EXPANDED Journal of The International Palm Society Founder: Dent Smith Betrock’sLANDSCAPEPALMS An illustrated, peer-reviewed quarterly devoted to The International Palm Society is a nonprofit corporation information about palms and published in March, Scientific information and color photographs for 126 landscape palms engaged in the study of palms. The society is inter- June, September and December by The International national in scope with worldwide membership, and the Palm Society, 810 East 10th St., P.O. Box 1897, This book is a revised and expanded version of formation of regional or local chapters affiliated with the Lawrence, Kansas 66044-8897, USA. international society is encouraged. Please address all Betrock’sGUIDE TOLANDSCAPEPALMS inquiries regarding membership or information about Editors: John Dransfield, Herbarium, Royal Botanic the society to The International Palm Society Inc., P.O. Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AE, United Box 1897, Lawrence, Kansas 66044-8897, USA. e-mail Kingdom, e-mail [email protected], tel. 44- [email protected], fax 785-843-1274. 20-8332-5225, Fax 44-20-8332-5278. Scott Zona, Fairchild Tropical Garden, 11935 Old OFFICERS: Cutler Road, Coral Gables, Miami, Florida 33156, President: Paul Craft, 16745 West Epson Drive, USA, e-mail [email protected], tel. 1-305- Loxahatchee, Florida 33470 USA, e-mail 667-1651 ext. 3419, Fax 1-305-665-8032. [email protected], tel. 1-561-514-1837. Associate Editor: Natalie Uhl, 228 Plant Science, Vice-Presidents: Bo-Göran Lundkvist, PO Box 2071, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853, USA, e- Pahoa, Hawaii 96778 USA, e-mail mail [email protected], tel. -

Systematics and Evolution of the Rattan Genus Korthalsia Bl

SYSTEMATICS AND EVOLUTION OF THE RATTAN GENUS KORTHALSIA BL. (ARECACEAE) WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO DOMATIA A thesis submitted by Salwa Shahimi For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences University of Reading February 2018 i Declaration I can confirm that is my own work and the use of all material from other sources have been properly and fully acknowledged. Salwa Shahimi Reading, February 2018 ii ABSTRACT Korthalsia is a genus of palms endemic to Malesian region and known for the several species that have close associations with ants. In this study, 101 new sequences were generated to add 18 Korthalsia species from Malaysia, Singapore, Myanmar and Vietnam to an existing but unpublished data set for calamoid palms. Three nuclear (prk, rpb2, and ITS) and three chloroplast (rps16, trnD-trnT and ndhF) markers were sampled and Bayesian Inference and Maximum Likelihood methods of tree reconstruction used. The new phylogeny of the calamoids was largely congruent with the published studies, though the taxon sampling was more thorough. Each of the three tribes of the Calamoideae appeared to be monophyletic. The Eugeissoneae was consistently resolved as sister to Calameae and Lepidocaryeae, and better resolved, better supported topologies below the tribal level were identified. Korthalsia is monophyletic, and novel hypotheses of species level relationships in Korthalsia were put forward. These hypotheses of species level relationships in Korthalsia served as a framework for the better understanding of the evolution of ocrea. The morphological and developmental study of ocrea in genus Korthalsia included detailed study using Light and Scanning Electron Microscopy for seven samples of 28 species of Korthalsia, in order to provide understanding of ocrea morphological traits. -

Working in the Garden

Leaders in Biodiversity Conservation, Montréal 23-25 October 2014 David Strauch Roxanne M. Adams Department of Geography Buildings and Grounds Management University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa <[email protected]> 2525 Maile Way, Honolulu, HI 96822 808.956.3611 Working in the Garden: Managing a postcolonial landscape in the academic background Rock and Plants: The Vision of the Campus as a Botanical Garden Joseph F. Rock (1884–1962) “Pohaku” 1908: Botanical collector, Hawai‘i Territorial Division of Forestry 1911: Botanist at College of Hawai‘i, in charge of the herbarium 1919: Professor of systematic botany 1955–1957: Botanized in Hawai‘i 1962: Awarded honorary PhD, while professor of Oriental studies http://huntbot.andrew.cmu.edu/hibd/Departments/Archives/Archives-HR/Rock.shtml http://huntbot.andrew.cmu.edu/hibd/Departments/Archives/Archives-HR/Rock.shtml Rock planting H. giffardianus, 1 September 1940 Photo: L. W. Bryan; HI Archives portrait no. 28 A Century’s Assemblage of Plants King Prajadhipok of Siam planted Botanists and horticulturalists added Chaulmoogra (Hydnocarpus plants collected on their work in the anthelmintica) in honor of Alice Ball Pacific and beyond; the golden variety of for her work on Hansenʻs Disease Delonix regia shown in the background using this this tree. was orinally collected at the Papeari Botanical Garden on Tahiti in 1975, by Horace Clay, whose name it now bears. Visiting scholars who came to give lectures at UH, like Carl Sandberg, often planted a tree while they were here. Arrival -

Pacific Island Palms Inventory List 2019 Please Contact Us for Pictures

Pacific Island Palms inventory list 2019 Please contact us for pictures, descriptions,sizes and prices of any Palm variety on our inventory list. Quantities are limited. Delivery available. (808)2802194 [email protected] Species Index Common Name Index 1. Actinokentia divaricata (red new leaf) 2. Archontophoenix maxima Walsh river king palm 3. Archontophoenix purpurea Purple king palm (purple crownshaft) 4. Areca macrocalyx (red crownshaft) Highland betel nut palm 5. Areca triandra (fragrant flower) 6. Areca vestiaria (orange crownshaft) Orange collar palm 7. Areca vestiaria (red crownshaft) 8. Areca vestiaria (yellow crownshaft) 9. Arenga australasica 10. Basselinia pancheri Micro kentia palm 11. Beccariophoenix madagascariensis Madagascar coconut palm 12. Bentinckia condapanna Lord Bentinck’s palm 13. Bismarckia nobilis (silver form) Bismark palm 14. Brahea dulcis Rock palm 15. Brassiophoenix drymophloeoides 16. Burretiokentia hapala Dreadlock palm 17. Burretiokentia vieillardii 18. Butia eriospatha Woolly Butia palm 19. Calyptrocalyx albertisianus Sunset palm 20. Calyptrocalyx leptostachys 21. Calyptronoma rivalis Manic palm 22. Carpentaria acuminata Carpentaria palm 23. Carpoxylon macrosperma Rip Curl palm 24. Caryota mitis Clustering fishtail palm 25. Caryota ophiopellis Snake skin palm 26. Caryota zebrina Zebra palm 27. Chambeyronia hookeri Red flame palm, 28. Chambeyronia macrocarpa Red feather palm 29. Copernicia alba Caranday palm 30. Copernicia berteroana 31. Cryosophila albida 32. Cyphophoenix nucele 33. Cyrtostachys lakka Sealing wax palm 34. Dictyosperma furfuraceum Princess palm 35. Dypsis albofarinosa (white petiole) 36. Dypsis ambositrae 37. Dypsis baronii (white crown shaft) 38. Dypsis basilonga 39. Dypsis cabadae Blue areca palm 40. Dypsis carlsmithii 41. Dypsis decaryi Triangle palm 42. Dypsis decipiens 43. Dypsis lanceolata 44. Dypsis lastelliana Redneck palm 45. -

An Introduction to the Palms of New Caledonia

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE PALMS OF NEW CALEDONIA JEAN-CHRISTOPHE PINTAUD Made in United States ofAmerica Reprinted from PALMS Vo!. 44, No. 3, 2000 ({) 2000 The International Palm Society PALMS Pintaud: Palms of New Caledonia Volume 44(3) 2000 JEAN-CHRISTOPHE PINTAUD An Introduction [RD (ex OR5TOM) Laboratoire de Botanique et d'Ecologie Végétale • to the Palms of Appliquée BPA5 98848 Nouméa Cedex New Caledonia New Caledonia 1. Pritchardiopsis jeanneneyi. One of the few Juveniles growing near the only known adult specimen, southern New Caledonia. The unique palm flora of New Caledonia has had a special appeal to palm enthusiasts, nurserymen and scientists ever since the earliest days of botanical exploration of the island. 132 PALMS 44(3): 132-140 PALMS Pintaud: Palms of New Caledonia Volume 44(3) 2000 Palms were among the first groups of native plants Moore and Uhl's treatment in our "Palms of New to be studied by the French botanists Brongniart Caledonia" (Hodel & Pintaud 1998). and Vieillard in the 1860-70s (Brongniart & Gris As an introduction to what is to be seen during 1864, Brongniart 1873, Vieillard 1873). At the the year 2000 IPS Biennial Meeting, 1will present same time, Linden, the great Belgian nurseryman sorne general features of New Caledonia palms, of the late 19th century appointed another which should be helpful for visitors to get a better botanist, Pancher, to collect seeds of New understanding of the palms they will encounter. Caledonia palms. A few years later, Linden's catalog included species such as Actinokentia Endemism divaricata and Cyphokentia macrostachya at prices Endemism is a magical word in New Caledonia, that only the most prominent palm collectors of most of the living things there being endemic-that the time, such as Dr Prochowski on the French is to say existing nowhere else in the world. -

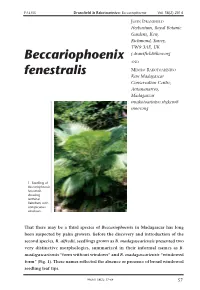

Beccariophoenix Fenestralis Showing Terminal Flabellum with Conspicuous Windows

PALM S Dransfield & Rakotoarinivo: Beccariophoenix Vol. 58(2) 2014 JOHN DRANSFIELD Herbarium, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AE, UK Beccariophoenix [email protected] AND MIJORO RAKOTOARINIVO fenestralis Kew Madagascar Conservation Centre, Antananarivo, Madagascar mrakotoarinivo.rbgkew@ moov.mg 1. Seedling of Beccariophoenix fenestralis showing terminal flabellum with conspicuous windows. That there may be a third species of Beccariophoenix in Madagascar has long been suspected by palm growers. Before the discovery and introduction of the second species, B. alfredii , seedlings grown as B. madagascariensis presented two very distinctive morphologies, summarized in their informal names as B. madagascariensis “form without windows” and B. madagascariensis “windowed form” (Fig. 1). These names reflected the absence or presence of broad windowed seedling leaf tips. PALMS 58(2): 57 –64 57 PALM S Dransfield & Rakotoarinivo: Beccariophoenix Vol. 58(2) 2014 In 1986 when a population of the charismatic just east of Ranomafana Est (Fig. 2). This tree Beccariophoenix madagascariensis was refound at was apparently quite well known to seed Mantadia, near the type locality in the collectors. The collection Larry made differed Andasibe area on the eastern escarpment of from collections from the Mantadia area in Madagascar (Dransfield 1988) it seemed the very short rather than extended peduncle, inconceivable that there might be more than the inflorescences thus appearing sessile when one species in the genus. For a couple of years, viewed from ground level. Then a third the Mantadia population was the only extant population of Beccariophoenix was discovered population known to botanists. Besides the by Henk Beentje at Sainte Luce near type collection made before 1915, it had also Taolagnaro (Fort Dauphin), it too with rather been collected near the Manampanihy River by short peduncles. -

2016 Plant Names Catalog Alphabetical by Botanical Name

2016 Plant Names Catalog Alphabetical by Botanical Name LOCATION(S) IN BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME(S) FAMILY GARDEN Acacia choriophylla cinnecord FABACEAE Plot 19b:Plot 50 Acacia cornigera bull-horn Acacia FABACEAE Plot 50 Acacia huarango FABACEAE Plot 153b long-spined Acacia macracantha FABACEAE Plot 164 acacia:steel Acacia Plot 176a:Plot Acacia pinetorum pineland acacia FABACEAE 176b:Plot 3a:Plot 97b Acacia sp. FABACEAE Plot 57a Acacia tortuosa poponax FABACEAE Plot 3a Acalypha hispida chenille plant EUPHORBIACEAE Plot 4 Acalypha hispida 'Alba' white chenille plant EUPHORBIACEAE Plot 4 Acalypha 'Inferno' EUPHORBIACEAE Plot 41a Acalypha siamensis 'Firestorm' EUPHORBIACEAE Plot 50 Acalypha siamensis 'Kilauea' EUPHORBIACEAE Plot 50 Acanthocereus sp. CACTACEAE Plot 138a:Plot 164 Acanthophoenix rubra ARECACEAE Plot 149:Plot 71c Acanthus sp. ACANTHACEAE Plot 50 Acer rubrum red maple ACERACEAE Plot 64 Acnistus arborescens wild tree tobacco SOLANACEAE Plot 128a:Plot 143 Plot 121:Plot 161:Plot 61:Plot 62:Plot 67:Plot paurotis Acoelorrhaphe wrightii ARECACEAE 69:Plot 71a:Plot palm:Everglades palm 72:Plot 76:Plot 78:Plot 81 shingle tree:pink Plot 131:Plot 133:Plot Acrocarpus fraxinifolius FABACEAE cedar 152 Acrocomia aculeata gru-gru ARECACEAE Plot 102:Plot 169 Acrocomia crispa ARECACEAE Plot 101b:Plot 102 Acropogon bullatus MALVACEAE Plot 33 Acrostichum aureum golden leather fern ADIANTACEAE Plot 159 Plot 195:Plot 3b:Plot Acrostichum danaeifolium leather fern ADIANTACEAE 63:Plot 69 Actephila ovalis PHYLLANTHACEAE Plot 151 Actinorhytis calapparia calappa palm ARECACEAE Plot 132:Plot 71c Plot 112:Plot 153b:Plot Adansonia digitata baobab MALVACEAE 3b Adansonia grandidieri MALVACEAE Plot 33 Adansonia gregorii MALVACEAE Plot 33 Adansonia madagascariensis Bozy MALVACEAE Plot 35 Adansonia rubrostipa Fony:Ringy MALVACEAE Plot 31 Adansonia sp. -

Arecaceae) in New Caledonia

PALMARBOR ISSN 2690-3245 Hodel and Moya López: New Caledonia Archontophoenicinae 2021-04: 1-27 The Typification and Nomenclature of the Genera and Species of the Subtribe Archontophoenicinae (Arecaceae) in New Caledonia DONALD R. HODEL AND CELIO E. MOYA LÓPEZ We reviewed the nomenclature and typification of the three genera, Actinokentia, Chambeyronia, and Kentiopsis, and the eight currently accepted species comprising the subtribe Archontophoenicinae (Arecaceae) in New Caledonia (Hodel and Pintaud 1998). We did this in preparation for a molecular-based taxonomic reassessment of this subtribe on the Island. We followed the rules set forth in Turland et al. (2018) and frequently refer to specific article numbers (Art.) upon which we based our findings. We made no taxonomic changes at this time and accepted the species as presented in the major on-line taxonomic databases (Tropicos, IPNI, The Plant List, Govaerts et al. 2021). Unless otherwise noted, all specimens were seen as high- resolution digital images (without designation as such in the text). Co-author Hodel took the photographs of living plants in habitat in New Caledonia in 1995 and 1996 and scanned the original transparencies to present here. Actinokentia Dammer, Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 39: 20 (1906). Type species: Actinokentia divaricata Dammer. Actinokentia divaricata Dammer, Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 39: 21 (1906). Fig. 1. Type. New Caledonia. [Province Sud, commune Nouméa], “mont Conghi [Koghi],” fl., ft., no date, Pancher 765 (lectotype [first-step]: Beccari 1920: 322, P; lectotype [second-step]: designated here, P 00065056; isolectotypes: P 00065057, P 00065058, P 00065059, P 00065060, P 00065061, P 00065063, P 00065064). When he described Actinokentia divaricata, Dammer (1906) cited five different specimens in the protologue: Pancher 765, Balansa 1969, Balansa 1969a, Balansa 770, and Balansa 770a, creating syntypes (Art.