'Red Storm Ahead': Securitisation of Energy in US-China Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

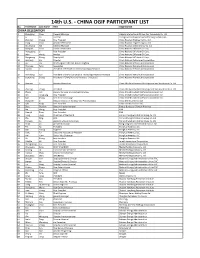

14TH OGIF Participant List.Xlsx

14th U.S. ‐ CHINA OGIF PARTICIPANT LIST No. First Name Last Name Title Organization CHINA DELEGATION 1 Zhangxing Chen General Manager Calgary International Oil and Gas Technology Co. Ltd 2 Li He Director Cheng Du Development and Reforming Commission 3 Zhaohui Cheng Vice President China Huadian Engineering Co. Ltd 4 Yong Zhao Assistant President China Huadian Engineering Co. Ltd 5 Chunwang Xie General Manager China Huadian Green Energy Co. Ltd 6 Xiaojuan Chen Liason Coordinator China National Offshore Oil Corp. 7 Rongguang Li Vice President China National Offshore Oil Corp. 8 Wen Wang Analyst China National Offshore Oil Corp. 9 Rongwang Zhang Deputy GM China National Offshore Oil Corp. 10 Weijiang Liu Director China National Petroleum Cooperation 11 Bo Cai Chief Engineer of CNPC RIPED‐Langfang China National Petroleum Corporation 12 Chenyue Feng researcher China National Petroleum Corporation 13 Shaolin Li President of PetroChina International (America) Inc. China National Petroleum Corporation 14 Xiansheng Sun President of CNPC Economics & Technology Research Institute China National Petroleum Corporation 15 Guozheng Zhang President of CNPC Research Institute(Houston) China National Petroleum Corporation 16 Xiaquan Li Assistant President China Shenhua Overseas Development and Investment Co. Ltd 17 Zhiming Zhang President China Shenhua Overseas Development and Investment Co. Ltd 18 Zhang Jian deputy manager of unconventional gas China United Coalbed Methane Corporation Ltd 19 Wu Jianguang Vice President China United Coalbed Methane Corporation Ltd 20 Jian Zhang Vice General Manager China United Coalbed Methane Corporation Ltd 21 Dongmei Li Deputy Director of Strategy and Planning Dept. China Zhenhua Oil Co. Ltd 22 Qifa Kang Vice President China Zhenhua Oil Co. -

Clean Tech Handbook for Asia Pacific May 2010

Clean Tech Handbook for Asia Pacific May 2010 Asia Pacific Clean Tech Handbook 26-Apr-10 Table of Contents FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................. 16 1 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................... 19 1.1 WHAT IS CLEAN TECHNOLOGY? ........................................................................................................................ 19 1.2 WHY CLEAN TECHNOLOGY IN ASIA PACIFIC? .......................................................................................................19 1.3 FACTORS DRIVING THE CLEAN TECH MARKET IN ASIA PACIFIC .................................................................................20 1.4 KEY CHALLENGES FOR THE CLEAN TECH MARKET IN ASIA PACIFIC ............................................................................20 1.5 WHO WOULD BE INTERESTED IN THIS REPORT? ....................................................................................................21 1.6 STRUCTURE OF THE HANDBOOK ........................................................................................................................ 21 PART A – COUNTRY REVIEW.......................................................................................................................... 22 2 COUNTRY OVERVIEW.......................................................................................................................... -

2016 State Utility Commissioners Clean Energy Policy and Technology Leadership Mission to China

2016 STATE UTILITY COMMISSIONERS CLEAN ENERGY POLICY AND TECHNOLOGY LEADERSHIP MISSION TO CHINA SPONSORED BY OFFICE OF CLEAN COAL & CARBON MANAGEMENT US-CHINA CLEAN ENERGY RESEARCH CENTER US DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY BEIJING, HAIYANG, SHANGHAI, AND ORDOS TRIP REPORT ROBERT W. GEE, PRESIDENT SHERI S. GIVENS, SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT .... Gee Strategies 11111 Group,LLc WASHINGTON | AUSTIN WITH SPECIAL APPRECIATION TO: COMMISSIONER TRAVIS KAVULLA, MONTANA COMMISSIONER DAVID ZIEGNER, INDIANA COMMISSIONER LIBBY JACOBS, IOWA COMMISSIONER SANDY JONES, NEW MEXICO COMMISSIONER SHERINA MAYE EDWARDS, ILLINIOIS JOE GIOVE, US DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY a1J1 6e e Strategies Group,LLc 11111 December 1, 2016 Dr. Robert C. Marlay US Director US-China Clean Energy Research Center Office of International Affairs US Department of Energy Mr. David Mohler Deputy Assistant Secretary for Clean Coal and Carbon Management Office of Fossil Energy US Department of Energy Dear Dr. Marlay and Mr. Mohler: We are forwarding you the 2016 Trip Report for the State Utility Commissioners Clean Energy Policy and Technology Leadership Mission to China As the attached report outlines, each goal we set out to accomplish at the outset of the mission was achieved, and we believe that the lessons learned by the participating state utility commissioners will yield dividends to the US Government and Department of Energy. We extend my deep gratitude for your support for this mission. Sincerely, Robert W. Gee President Gee Strategies Group LLC Sheri S. Givens Sheri S. Givens Senior Vice President Gee Strategies Group LLC Attachment TABLE OF CONTENTS Background 1 Delegation Meetings 2 Beijing 3 Haiyang 33 Shanghai 38 Ordos 44 Major Mission Accomplishments 56 Recommendations 58 Appendices A. -

Process Industry in China Future Developement and Government Regulation by Gao Peng and Lin Song, Innovation Norway, China

Process Industry in China Future developement and government regulation by Gao Peng and Lin Song, Innovation Norway, China Condensed report Kapittel 2 Table of contents Table of contents ............................................................................................................................................. ii Executive summary ......................................................................................................................................... iii Preface ........................................................................................................................................................... vi Acronyms and abbreviations ......................................................................................................................... vii 1. China’s process industry in general ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Chinese Process Industry brief introduction ................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Some of the relevant process industries’ development............................................................................... 2 1.3 Cooperation with Norway ............................................................................................................................ 3 1.4 Influence from the trade war with US-in China’s perspective ..................................................................... 3 1.5 Influence from COVID-19 -

LNG Exports from US and Russia to Help Create New Gas World Order

p1-4_LNG 3 15/01/2018 09:52 Page 1 36 pages essential LNG news! January 2018 In this issue: LNG exports from US and Russia 1 LNG exports from US and Russia to help to help create new gas world order create new gas world Latest report from International Energy Agency outlines wider role for flexible and abundant gas in energy transition order Latest report from International A new natural gas world order is Energy Agency outlines wider role emerging as US liquefied natural gas for flexible and abundant gas in energy transition production helps to accelerate a shift towards a more flexible, liquid and global 3 Australia’s Wheatstone market, accompanied by new Russian project joined by Yamal shipments of LNG to Asia and by future and Cove Point plants pipeline volumes. for early 2018 ramp-up The France-based International Three latest liquefaction plants Energy Agency said in its World Energy were developed to cope with widely Outlook that LNG would account for differing climatic conditions almost 90 percent of the projected growth 5 A round-up of latest in long-distance natural gas trade from events, company and now until 2040. industry news Qualities For the Record “Ensuring that gas remains affordable 20 Chart Industries and secure, beyond the current period outlines brazed of ample supply and lower prices, is aluminum heat critical for its long-term prospects,” the The new Yamal LNG export plant in the Russian Arctic region exchanger benefits for IEA stated. LNG plant optimisation However, the IEA added that with anticipated changes in the wider gas one-third, due to more reliance on highly Doug Ducote and Paul Shields of few exceptions - most notably the route market,” it added. -

Facing China's Coal Future

Facing China’s Coal Future Prospects and Challenges for Carbon Capture and Storage Dennis Best and Ellina Levina The views expressed in this working paper do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of the International Energy Agency (IEA) Secretariat or of its individual member countries. This paper is a work in progress and/or is produced in parallel with or contributing to other IEA work or formal publication; comments are welcome, directed to [email protected] © OECD/IEA, 2012 ©OECD/IEA 2012 INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY The International Energy Agency (IEA), an autonomous agency, was established in November 1974. Its primary mandate was – and is – two-fold: to promote energy security amongst its member countries through collective response to physical disruptions in oil supply, and provide authoritative research and analysis on ways to ensure reliable, affordable and clean energy for its 28 member countries and beyond. The IEA carries out a comprehensive programme of energy co-operation among its member countries, each of which is obliged to hold oil stocks equivalent to 90 days of its net imports. The Agency’s aims include the following objectives: n Secure member countries’ access to reliable and ample supplies of all forms of energy; in particular, through maintaining effective emergency response capabilities in case of oil supply disruptions. n Promote sustainable energy policies that spur economic growth and environmental protection in a global context – particularly in terms of reducing greenhouse-gas emissions that contribute to climate change. n Improve transparency of international markets through collection and analysis of energy data. n Support global collaboration on energy technology to secure future energy supplies and mitigate their environmental impact, including through improved energy efficiency and development and deployment of low-carbon technologies. -

Meeting China's Shale Gas Goals

MEETING CHINA’S SHALE GAS GOALS David Sandalow, Jingchao Wu, Qing Yang, Anders Hove and Junda Lin SEPTEMBER 2014 WORKING DRAFT FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Note on Units ....................................................................................................................................................... 12 1. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................................... 13 A. The Resource ........................................................................................................................................... 13 B. The Industry ............................................................................................................................................. 13 C. Shale Gas Production to Date ............................................................................................................ 15 2. U.S. EXPERIENCE ............................................................................................................................................... 17 3. CURRENT POLICIES ......................................................................................................................................... 19 A. Chinese Energy Policies ..................................................................................................................... -

China's Engagement in Global Energy Governance

PARTNER COUNTRY SERIES China’s Engagement in Global Energy Governance PARTNER COUNTRY SERIES China’s Engagement in Global Energy Governance Julia Xuantong Zhu INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY The International Energy Agency (IEA), an autonomous agency, was established in November 1974. Its primary mandate was – and is – two-fold: to promote energy security amongst its member countries through collective response to physical disruptions in oil supply, and provide authoritative research and analysis on ways to ensure reliable, affordable and clean energy for its 29 member countries and beyond. The IEA carries out a comprehensive programme of energy co-operation among its member countries, each of which is obliged to hold oil stocks equivalent to 90 days of its net imports. The Agency’s aims include the following objectives: n Secure member countries’ access to reliable and ample supplies of all forms of energy; in particular, through maintaining effective emergency response capabilities in case of oil supply disruptions. n Promote sustainable energy policies that spur economic growth and environmental protection in a global context – particularly in terms of reducing greenhouse-gas emissions that contribute to climate change. n Improve transparency of international markets through collection and analysis of energy data. n Support global collaboration on energy technology to secure future energy supplies and mitigate their environmental impact, including through improved energy efficiency and development and deployment of low-carbon technologies. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science the Tiger and The

The London School of Economics and Political Science The Tiger and the Dragon: A Neoclassical Realist perspective of India and China in the oil industry in West Africa Rajneesh Verma A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, April 2013 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98,338 words. 2 Acknowledgments Writing a PhD thesis can be an arduous task, a task made less convoluted, exciting, challenging and full- filling by the support of many. It gives me great pleasure to thank my doctoral supervisor Dr Chris Alden. It was an honour and privilege to be supervised by Dr Alden, a person with a humane heart. Dr Alden has been fundamental and instrumental in providing support in every way possible to ensure that the thesis is completed. -

Exchange and Training on Clean Coal Technology and Clean Energy Policy

Exchange and Training on Clean Coal Technology and Clean Energy Policy APEC Energy Working Group December 2019 APEC Project: EWG 14 2018 S Produced by YU Zhufeng Clean Coal Technology Transfer Program Joint Operation Center, APSEC Research Garden of Shenhua Innovation Base, Future Science Park Changping District, Beijing 102211, China Telephone: +86 10 5733 9975 Fax: +86 10 5733 9999 For Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Secretariat 35 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119616 Tel: (65) 68919 600 Fax: (65) 68919 690 Email: [email protected] Website: www.apec.org © 2019 APEC Secretariat APEC#219-RE-01.18 Preface In global power supply, coal plays an important role, especially in the Asia- Pacific region, where coal reserves and production accounted for 30% and 70% respectively over the world. The endowment, availability and economy of coal determines that coal power will remain a significant base energy source in the world, especially in the Asia-Pacific economies for quite a long time. Meanwhile in the future, over half of the increase of global coal power supply will come from the Asia-Pacific economies. With the trend of low-carbon development and green economy around the world, all economies are actively speeding up the development of clean energy such as renewable energy. In the meantime, they are improving energy efficiency and reducing carbon dioxide emissions through energy conservation and enhancing the clean utilization of fossil energy. China is the world's largest consumer and producer of coal. The Chinese government is actively promoting the "Four Revolutions and One Cooperation" (namely the revolutions of energy consumption, energy supply, energy technology and energy system, and strengthened all-round international cooperation) energy strategy. -

Gr Ande C Hine & Mon Golie

Janvier 2019 REVUE DE PRESSE POLE DEVELOPPEMENT DURABLE, ENERGIE, TRANSPORTS MONGOLIE SOMMAIRE GRANDE & CHINE GRANDE Energie ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Charbon, pétrole et gaz naturel ............................................................................................................. 5 Trade war cuts U.S. LNG exports to China in 2018 (Reuters) ..................................................................................... 5 China’s CNOOC hols LNG offshore as warm winter cuts spot demand (Reuters) .............................................. 6 China’s record 2018 oil, gas imports may be cresting wave as industry slows down (Reuters) ................ 7 Analysis: China’s LNG demand growth to slow in 2019 on domestic production, pipeline imports (S&P Global Platts) ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Total-invested China gas field pumps record 2,24 bcm in 2018 (Reuters) ....................................................... 10 China firms funding coal plants offshore as domestic curbs bite: study (Reuters) ........................................ 11 As winter grips rural China, who’s really paying the price for Beijing’s clean air plan (South China Morning Post) ............................................................................................................................................................................... -

Biofuels - at What Cost ?

BIOFUELS - AT WHAT COST ? Government support for ethanol and biodiesel in China November 2008 Prepared by : the Global Subsidies Initiative of the International Institute for Sustainable Development Based on a report commissioned by the GSI from the Energy Research Institute of the National Development and Reform Commission Biofuels – At What Cost? Government support for ethanol and biodiesel in China November 2008 Prepared by the Global Subsidies Initiative (GSI) of the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) Geneva, Switzerland Based on a report commissioned by GSI from the Energy Research Institute of the National Development and Reform Commission, Beijing, China i | i Biofuels – At What Cost? Government support for ethanol and biodiesel in China November 2008 Prepared by the Global Subsidies Initiative (GSI) of the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) Geneva, Switzerland Based on a report commissioned by GSI from the Energy Research Institute of the National Development and Reform Commission, Beijing, China i | i © 2008, International Institute for Sustainable Development Acknowledgments The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) contributes to sustainable development by advancing policy recommendations on international trade and investment, This report is based on an original study commissioned by the Global Subsidies Initiative economic policy, climate change and energy, measurement and assessment, and sustainable (GSI) from the Energy Research Institute (ERI) of the National Development and Reform natural resources management. Through the Internet, we report on international Commission (NDRC), China. The original report can be found at www.globalsubsidies.org. negotiations and share knowledge gained through collaborative projects with global partners, The ERI report was substantially expanded by Emma Cole, a private consultant, based in resulting in more rigorous research, capacity building in developing countries and better Canberra, Australia.