Kalamkari, the Art of Painting with Natural Dyes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Batik V I S U a L M a G I C O N F a B R I C

EZCC Batik V I S U A L M A G I C O N F A B R I C Batik is an ancient form of a manual wax- dyes. India had abundant sources of cotton, resist dyeing process, which is practiced in as well as several plant and mineral sources Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan, China, Thailand, from which the dyes could be extracted. Philippines, Sri Lanka, Nigeria, Middle East, Traditional colours of batik have always India and some other countries. The exact been indigo, dark brown and white – origin of batik is not known, but it is widely colours that represent the gods of the practiced in Indonesia. In India, the resist Hindu trinity – Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. method of printing designs on fabrics can The art probably declined over the years as be traced back 2000 years, to the 1st it was a tedious and labour intensive century AD. Religious tapestries of ancient process. India bear testimony of the fact that batik The word batik means ‘wax writing’, and printing has existed in our country for a involves three major processes – waxing, long time. Also, traditionally batik was done dyeing and de-waxing – and several sub- only on cotton and silk fabrics, using natural processes – starching, stretching the fabric dipped in boiling water to melt off the layers on a frame and outlining the design using a of wax, to get the final pattern. Colours are special Kalamkari pen. Depending on the significantly changed by the preceding number of colours being used, creating a colour on the fabric as the process involves batik print on a fabric can take several days. -

Traditional Indian Textiles Students Handbook + Practical Manual Class XII

Traditional Indian Textiles Students Handbook + Practical Manual Class XII CENTRAL BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION Shiksha Kendra, 2, Community Centre, Preet Vihar, Delhi-110301 In collaboration with National Institute of Fashion Technology Traditional Indian Textiles – Class XII Students Handbook + Practical Manual PRICE : ` FIRST EDITION : 2014 © CBSE, India COPIES : No Part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. PUBLISHED BY : The Secretary, Central Board of Secondary Education, Shiksha Kendra, 2, Community Centre, Preet Vihar, Delhi - 110301 DESIGNED & LAYOUT : M/s. India Offset Press, A-1, Mayapuri Industrial Area, Phase-1, New Delhi - 110064 Hkkjr dk lafo/kku mísf'kdk ge Hkkjr ds yksx Hkkjr dks ,d ^¿lEiw.kZ izHkqRo&laiUu lektoknh iaFkfujis{k yksdra=kRed x.kjkT;À cukus ds fy,] rFkk mlds leLr ukxfjdksa dks % lkekftd] vkfFkZd vkSj jktuSfrd U;k;] fopkj] vfHkO;fDr] fo'okl] /keZ vkSj mikluk dh Lora=rk] izfr"Bk vkSj volj dh lerk izkIr djkus ds fy, rFkk mu lc esa O;fDr dh xfjek vkSj jk"Vª dh ,drk vkSj v[k.Mrk lqfuf'pr djus okyh ca/kqrk c<+kus ds fy, n`<+ladYi gksdj viuh bl lafo/kku lHkk esa vkt rkjh[k 26 uoEcj] 1949 bZñ dks ,rn~}kjk bl lafo/kku dks vaxhÑr] vf/kfu;fer vkSj vkRekfiZr djrs gSaA 1- lafo/kku ¼c;kfyloka la'kks/ku½ vf/kfu;e] 1976 dh /kkjk 2 }kjk ¼3-1-1977½ ls ÞizHkqRo&laiUu yksdra=kRed x.kjkT;ß ds LFkku ij izfrLFkkfirA 2- lafo/kku ¼c;kfyloka la'kks/ku½ -

Veeraa Enterprises Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Veeraa Enterprises Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India We are one of the leading manufacturers, suppliers and exporters of fancy fabrics like patchwork, pintuck and printed fabrics. These are used to make a variety of home furnishings and textile items like curtains and covers. Veeraa Enterprises Profile Established in the year 1996, we, “Veeraa Enterprises”, are a noted manufacturer, supplier and exporter of patchwork fabrics, fancy patchwork fabrics, zig zag patchwork fabrics, embroidery patchworks fabrics, blue patchwork fabrics, black patchwork fabrics, US patchwork fabrics, frill patchwork fabrics, denim frinches with applique fabrics, border embroidery applique fabrics, pintuck fabrics, embroidered pintuck fabric, denim pintuck fabrics, printed fabrics, printed patchwork fabrics, printed dobby fabrics, batik print fabrics, batik blue fabrics, kalamkari fabrics, checks fabrics, yarn dyed checks fabrics, madras checks fabrics. These are manufactured using quality raw material and are highly praised for attributes such as colorfastness, durability, ease in washing & maintaining and tear resistance. It is largely due to the quality of our fabrics that we have succeeded in putting together an esteemed group of loyal clients and attain high level of customer satisfaction. Our main business motive is to provide best fabrics at market-leading prices. Our team is aided by our sound infrastructure at all stages of production to ensure that the quality of our fabrics remains high. With the support of an able team and a good infrastructure, we have acquired a special place for ourselves in the industry of textiles and furnishings. As we fully understand the demands of our customers, they have a pleasurable experience while dealing with us. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 27:2 — Fall 2015 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Fall 2015 Textile Society of America Newsletter 27:2 — Fall 2015 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 27:2 — Fall 2015" (2015). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 71. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/71 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 27. NUMBER 2. FALL, 2015 Cover Image: Collaborative work by Pat Hickman and David Bacharach, Luminaria, 2015, steel, animal membrane, 17” x 23” x 21”, photo by George Potanovic, Jr. page 27 Fall 2015 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Ellyane Hutchinson (Website Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) and Vita Plume (Vice President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016" (2016). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 73. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/73 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 28. NUMBER 1. SPRING, 2016 TSA Board Member and Newsletter Editor Wendy Weiss behind the scenes at the UCB Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, durring the TSA Board meeting in March, 2016 Spring 2016 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (Membership & Communications Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives. -

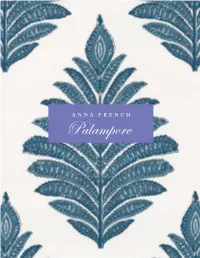

Palampore Palampore

Palampore Palampore Named after lustrous Indian painted fabric panels, Palampore combines exotic Indienne-inspired and indigenous designs in two coordinating collections of fabrics and wallcoverings. The love affair with these decorated cloths became a European sensation in the 17th century as the vivid dying techniques were highly sought after and cotton was considered a luxury fabric for bedcovers. Patterns in these collections include tree of life elements – influenced by traditional palampore textiles – Jacobean flowers, unique leaf and paisley motifs, decorative small-scale designs and printed paperweaves, as well as a playful tiger, tribal and batik prints, that naturally complement the fabrics. Palampore Patterns LA PROVENCE Wallpaper–6 colorways Print Type: Screen Print Inherent of its French name, Match: Straight La Provence was inspired by a Vertical Repeat: 25¼" (64 cm) French document–an antique Width: 27" (69 cm) quilt. The large medallion radiates Made in USA with leaves and paisleys adorned with henna dot details. Printed Fabric–6 colorways Content: 100% Cotton Vertical Repeat: 24½" (62 cm) Horizontal Repeat: 26½" (67 cm) Width: 54" (137 cm) Made in UK JULES Wallpaper–7 colorways Print Type: Surface Print A tribal motif with repeating Match: Straight triangles. The matching print is Vertical Repeat: 5" (13 cm) on 100% cotton fabric. Width: 27" (69 cm) Made in UK Printed Fabric–6 colorways Content: 100% Cotton Vertical Repeat: 10¼" (26 cm) Horizontal Repeat: 6¾" (17 cm) Width: 54" (137 cm) Made in India TANSMAN Paperweave–5 colorways Print Type: Digital on Paperweave The color blocks of Tansman Match: Straight are reminiscent of traditional Vertical Repeat: 30½" (77 cm) African cloths. -

Improving the Colour Fastness of the Selected Natural Dyes on Cotton (Improving the Sunlight Fastness and Washfastness of the Eucalyptus Bark Dye on Cotton)

IOSR Journal of Polymer and Textile Engineering (IOSR-JPTE) e-ISSN: 2348-019X, p-ISSN: 2348-0181, Volume 1, Issue 4 (Sep-Oct. 2014), PP 27-30 www.iosrjournals.org Improving the Colour Fastness of the Selected Natural Dyes on Cotton (Improving the sunlight fastness and washfastness of the eucalyptus bark dye on cotton) R.Prabhavathi1, Dr.A.Sharada Devi2 & Dr. D. Anitha3 Department of Apparel and Textiles, College of Home Science, Acharya N.G Ranga Agricultural University (ANGRAU)Saifabad, Hyderabad -30, India. Part-V Abstract: This paper reports the improving the colourfastness of the natural dye with dye fixing agents, extraction of the colourants from natural sources; effects of different mordants and mordanting methods; selection of fixing agents; dyeing variables; post-treatment process and analysis of colour improvement parameters with fixing agents for cotton dyed with natural dye; assessed colour improvement with colourfastness test. Key words: Eucalyptus Bark natural dye, fixing agents, coloufastness, shade variations with dye fixing agents I. Introduction: In India, dyes from natural sources have ancient history and can trace their route to antiquity. It is interesting to note that India is one of the few civilizations to perfect the art of fixing natural dye to the cloth. Indian textiles were greatly valued and sought after for their colours and enduring qualities. Like most ancient Indian arts and crafts, part of the knowledge and expertise of natural dyes has traditionally passed down from the master crafts man to his disciples. Even though scientists have paid considerable attention in the post independence period to study the plants in relation to their pharmaceutical use, very little attention was paid to study the plants as sources of dyes and colourants. -

Kalamkari – the Block Prints of Machalipatnam

KALAMKARI – THE BLOCK PRINTS OF MACHALIPATNAM Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. Regions 3. Producer communities 4. Raw materials 5. Tools 6. Production process a. Elaboration of dyeing processes b. Elaboration of printing process c. Degumming and washing d. Boiling e. Final processing 7. List of products 8. Appendix 1. Introduction Kalamkari is the craft of painting and printing on fabrics. It derives its name from kalam or pen with which the patterns are traced. It is an art form that was developed both for decoration and religious ornamentation. 1.1 History The discovery of a resist-dyed piece of cloth on a silver vase at the ancient site of Harappa confirms that the tradition of Kalamkari is very old. Even the ancient Buddhist Chaitya Viharas were decorated with Kalamkari cloth. Little was known about printed Indian cotton before the archeological findings at Fostat, near Cairo. The discovery unearthed a hoard of fragments of printed Indian cotton supposed to have been exported in the 18th century from the western shores of India. A study of some of these Fostat finds in 1938 by Pfisher, who traced them to India, brought to light evidence of a tradition of those fabrics that were actually block printed and resist-dyed with indigo. Before the artificial synthesis of indigo and alizerine into dyestuffs, blues and reds were traditionally extracted from the plant indigofera tinctoria and rubia tinctoria. alizerine, commonly used as a coloring agent, was found in ancient times in madder. The madder root, rubia, widely used in India and chay (chay is oldenlandia), the root of oldenlandia umbellata, were highly estimated as fine sources of red in the south. -

The Textile Museum Thesaurus

The Textile Museum Thesaurus Edited by Cecilia Gunzburger TM logo The Textile Museum Washington, DC This publication and the work represented herein were made possible by the Cotsen Family Foundation. Indexed by Lydia Fraser Designed by Chaves Design Printed by McArdle Printing Company, Inc. Cover image: Copyright © 2005 The Textile Museum All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means -- electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise -- without the express written permission of The Textile Museum. ISBN 0-87405-028-6 The Textile Museum 2320 S Street NW Washington DC 20008 www.textilemuseum.org Table of Contents Acknowledgements....................................................................................... v Introduction ..................................................................................................vii How to Use this Document.........................................................................xiii Hierarchy Overview ....................................................................................... 1 Object Hierarchy............................................................................................ 3 Material Hierarchy ....................................................................................... 47 Structure Hierarchy ..................................................................................... 55 Technique Hierarchy .................................................................................. -

I – Traditional Textiles of India – Sfda 1301

UNIT – I – TRADITIONAL TEXTILES OF INDIA – SFDA 1301 1 Introduction : The term 'Textile' is a Latin word originating from the word 'texere' which means 'to weave' Textile refers to a flexible material comprising of a network of natural or artificial fibers, known as yarn. Textiles are formed by weaving, knitting, crocheting, knotting and pressing fibers together. Textile Museum is that specialized category of museum which primarily preserves different types of textile and textile products. Indian textile enjoys a rich heritage and the origin of textiles in India traces back to the Indus valley Civilization where people used homespun cotton for weaving their clothes. Rigveda, the earliest of the Veda contains the literary information about textiles and it refers to weaving. Ramayana and Mahabharata, the eminent Indian epics depict the existence of wide variety of fabrics in ancient India. These epics refer both to rich and stylized garment worn by the aristocrats and ordinary simple clothes worn by the common people. The contemporary Indian textile not only reflects the splendid past but also cater to the requirements of the modern times. The rich tradition of textile in India has been favored by a number of factors. The favorable factors leading to the extensive growth of textile tradition in India follows. Easy availability of abundant raw materials like cotton, wool, silk, jute and many more Widely prevalent social customs Variety of distinct local culture Constructive geographic and climatic conditions Each and every region of India contributes in creating a myriad of textile tradition. The hilly region of the country produces a rich variety of woolen textiles. -

Product Catalogue

tisser sareesHAND PAINTED Madhubani | Pattachitra | Warli | Kalamkari | Kerela Hand Painted CHANDERI Buti | Plain | Gold Zari | Shibori | Indigo | Block Print LINEN Pure Linen | Tussar by Linen | Linen Jamdani | Digital Print TUSSAR Moonga | Gidcha | Plain | Block Print HAND-EMBROIDERED Mirror work | Kasuti work | Applique | Kantha | Mangalgiri MAHESHWARI Resham Border | Temple Border | Chatai Border | Shatranj Diya leher | Badi leher | Choka COTTON - SILK Mahapore | Velvet | Gorod | Temple Border COTTON Bishnupur | Cut Shut | Bhagalpur Silk | Kosa Silk Kolkata Cotton Fusion | Khes | Khadi | Khes Pom-Pom BLOCK PRINTED Maddhamoni | Gamcha | Muslin | Tant Indigo | Shibori | Baug | Ajrakh | Pigment | Chuna patri IKAT Sinlge Ikat | Double Ikat CHANDERI - SHIBORI MAHESHWARI - HALF STRIPE COTTON SILK - MIRROR WORK KOSA SILK HAND PAINTED Madhubani | Pattachitra | Warli | Kalamkari Abstract | Orissa Handpainted | Warli Zaripalla CHANDERI Buti | Indigo | Shibori | Chanderi dupattas Block Print | Silk | Pigment | Bagroo HAND-EMBROIDERED Kutch | Applique | Chikan | Kasuti Dunkand | Crotchet | Kantha | Cotton MAHESHWARI Leheriya Border | Kosa Pallu | Zari Pallla | Zari Patta | Resham Border Chatai | Zigzag Border Diya Border | Missing Lines | Tissue IKAT Ikat Silk | Ikat Cotton | Missing Lines TUSSAR Dupion | Gidcha | Tapti| Silk TIE-DYE Bandhni | Batik | Patterned BLOCK PRINTED Bagroo | Pigment |Baug | Ajrakh | Indigo | Kalamkari COTTON Siri Giri | Wave Border | Temple Border | Silk Border | Semi Khadi | Plain KOTA Plain | Block Print | Embroidary -

THE HERITAGE of INDIA: INDIAN TRADITIONAL TEXTILE Dr.Prakashkhatwani1 ,Prunal Khawani2 1 Sr

THE HERITAGE OF INDIA: INDIAN TRADITIONAL TEXTILE Dr.PrakashKhatwani1 ,Prunal Khawani2 1 Sr. professor,Textile Technology/SCET,Surat(India) 2Fashion and Textile Department/INIFD, Surat / JJT University Rajasthan (India) ABSTRACT Indian traditional textile had a wide range of variety of fabrics. The objective behind this paper is to knowaboutdifferent variety of traditional fabrics and get help from some of the oldest textiles to reform that art. KEYWORDS :BLOCK PRINT, HANDLOOM WEAVING, ANCIENT TIME, IKAT, RESIST PRINTING INTRODUCTION India has been very famous for its handicrafts and textile since very long, which is proved by many archaeological evidence. Very first evidence found were traces of purple dye at Mohenjo-Daro, which proves that cotton was spun and woven in India as early as 3000 B.C. In 300 B.C. Chanakya mentions that, textile was very important in internal and external trade. Even he mentioned in “Arthashastra“important centres for weavingcotton, silk and woollen cloth.The material used in spinning process were wool (urna), cotton (karpasa), hemp (tula) and flax (kusum).In that period mainly weaving was done by women and their wages dependedupon the thickness of yarn. During 100 A.D. Indian textiles became very popular because of its bright colours, among the Persians. Even Indian muslin was very famous in Rome with the name “nebula”, “gangetika”,and “venti”. Silk was also an exported product to Rome but raw material was imported from china. Even traditional Indian techniques were so advance in 600A.D. that Ajanta paintings attributed from this era were having embroidery, bandhna (tie and dye ) and patolu (ikat weaving ),brocading an muslin weaving fabrics.Between 1200 and 1500 A.D.