A Magazine of the Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2013-2014 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT(%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 209143 0.005310639 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 775695 0.019696744 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1618569 0.041099322 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 482558 0.012253297 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 534260 0.013566134 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 776771 0.019724066 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 201424 0.005114635 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 6550 0.00016632 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 1417145 0.035984687 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 546688 0.01388171 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 154046 0.003911595 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 18771 0.00047664 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 69244 0.00175827 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 153965 0.003909538 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 65899 0.001673333 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 172484 0.00437978 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 67128 0.00170454 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410114 STATE TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) -

The Spinning World: a Global History of Cotton Textiles, 1200-1850

PASOLD STUDIES IN TEXTILE HISTORY, 16 The Spinning World THE SPINNING WORLD A Global History of Cotton Textiles, 1200 –1850 EDITED BY GIORGIO RIELLO AND PRASANNAN PARTHASARATHI PASOLD RESEACH FUND 1 [copyright etc to come] CONTENTS List of Illustrations List of Maps List of Figures List of Tables Preface Introduction: Cotton Textiles and Global History Prasannan Parthasarath i and Giorgio Riello PART I World Areas of Cotton Textile Manufacturing 1. Cotton Textiles in the Indian Subcontinent, 1200–1800 Prasannan Parthasarathi 2. The Resistant Fibre: Cotton Textiles in Imperial China Harriet T. Zurndorfer 3. The First European Cotton Industry: Italy and Germany, 1100–1800 Maureen Fennell Mazzaoui 4. Ottoman Cotton Textiles: The Story of a Success that did not Last, 1500 –1800 Suraiya Faroqhi 5. ‘Guinea Cloth’: Production and Consumption of Cotton Textiles in West Africa before and during the Atlantic Slave Trade Colleen E. Kriger 6. The Production of Cotton Textiles in Early Modern South-East Asia William Gervase Clarence-Smith PART II Global Trade and Consumption of Cotton Textiles 7. The Dutch and the Indian Ocean Textile Trade Om Prakash 6 Contents 8. Awash in a Sea of Cloth: Gujarat, Africa, and the Western Indian Ocean, 1300–1800 Pedro Machado 9. Japan Indianized: The Material Culture of Imported Textiles in Japan, 1550–1850 Fujita Kayoko 10. Revising the Historical Narrative: India, Europe, and the Cotton Trade, c.1300–1800 Beverly Lemire 11. Cottons Consumption in the Seventeenth- and Eighteenth- Century North Atlantic Robert S. DuPlessis 12. Fashion, Race, and Cotton Textiles in Colonial Spanish America Marta Valentin Vicente 13. -

Development of Regional Politics in India: a Study of Coalition of Political Partib in Uhar Pradesh

DEVELOPMENT OF REGIONAL POLITICS IN INDIA: A STUDY OF COALITION OF POLITICAL PARTIB IN UHAR PRADESH ABSTRACT THB8IS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF fioctor of ^IHloKoplip IN POLITICAL SaENCE BY TABRBZ AbAM Un<l«r tht SupMvMon of PBOP. N. SUBSAHNANYAN DEPARTMENT Of POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALI6ARH (INDIA) The thesis "Development of Regional Politics in India : A Study of Coalition of Political Parties in Uttar Pradesh" is an attempt to analyse the multifarious dimensions, actions and interactions of the politics of regionalism in India and the coalition politics in Uttar Pradesh. The study in general tries to comprehend regional awareness and consciousness in its content and form in the Indian sub-continent, with a special study of coalition politics in UP., which of late has presented a picture of chaos, conflict and crise-cross, syndrome of democracy. Regionalism is a manifestation of socio-economic and cultural forces in a large setup. It is a psychic phenomenon where a particular part faces a psyche of relative deprivation. It also involves a quest for identity projecting one's own language, religion and culture. In the economic context, it is a search for an intermediate control system between the centre and the peripheries for gains in the national arena. The study begins with the analysis of conceptual aspect of regionalism in India. It also traces its historical roots and examine the role played by Indian National Congress. The phenomenon of regionalism is a pre-independence problem which has got many manifestation after independence. It is also asserted that regionalism is a complex amalgam of geo-cultural, economic, historical and psychic factors. -

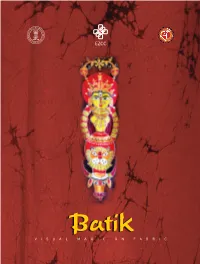

Batik V I S U a L M a G I C O N F a B R I C

EZCC Batik V I S U A L M A G I C O N F A B R I C Batik is an ancient form of a manual wax- dyes. India had abundant sources of cotton, resist dyeing process, which is practiced in as well as several plant and mineral sources Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan, China, Thailand, from which the dyes could be extracted. Philippines, Sri Lanka, Nigeria, Middle East, Traditional colours of batik have always India and some other countries. The exact been indigo, dark brown and white – origin of batik is not known, but it is widely colours that represent the gods of the practiced in Indonesia. In India, the resist Hindu trinity – Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. method of printing designs on fabrics can The art probably declined over the years as be traced back 2000 years, to the 1st it was a tedious and labour intensive century AD. Religious tapestries of ancient process. India bear testimony of the fact that batik The word batik means ‘wax writing’, and printing has existed in our country for a involves three major processes – waxing, long time. Also, traditionally batik was done dyeing and de-waxing – and several sub- only on cotton and silk fabrics, using natural processes – starching, stretching the fabric dipped in boiling water to melt off the layers on a frame and outlining the design using a of wax, to get the final pattern. Colours are special Kalamkari pen. Depending on the significantly changed by the preceding number of colours being used, creating a colour on the fabric as the process involves batik print on a fabric can take several days. -

Kalamkari, the Art of Painting with Natural Dyes

Chitrolekha International Magazine on Art and Design, (ISSN 2231-4822), Vol. 5, No. 2, 2015 URL of the Issue: www.chitrolekha.com/v5n2.php Available at www.chitrolekha.com/V5/n2/08_Kalamkari.pdf Kolkata, India. © AesthetixMS Included in Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOHOST, Google Scholar, WorldCat etc. Kalamkari, the Art of Painting with Natural Dyes Sharad Chandra Independent Researcher Kalamkari means painting with a pen. It is an exquisite form of textile art with a heritage dating back to the ancient times. The origin of the term can be traced to the early period of alliance between the Persian and Indian trade merchants which identified all painted textile art from India as Kalamkari. ‘Kalam’ is the Persian word for pen, and ‘kari’ in Urdu implies the craftsmanship involved. Hence, ‘Kalamkari’ denotes the myriad manifestations of hand painted textiles with natural dyes. The pen referred to in the term is a short piece of bamboo or date- palm stick, shaped and pointed at its end to form a nib. Created without the use of chemicals or machine Kalamkari art is entirely a handicraft using natural or vegetable dyes and metallic salts called mordants to fix the dye into the cotton fibers. An exact resist process, complex and careful dyeing, sketching and painting of the design and, occasionally, even the addition of gold or silver tinsel into it are the other integral components of this art. The Kalamkari works are mostly produced in the small towns of Kalahasti, Machilipatnam and other interior regions of Andhra Pradesh by rural craftsmen and women, and is a household occupation passed from generation to generation as heritage. -

FRUIT of the LOOM' Cotton and Muslin in South Asia

1 ‘FRUIT OF THE LOOM’ Cotton and Muslin in South Asia Rosemary Crill Muslin, the supremely fine cotton fabric in honour of which this festival and this gathering are being held, has been one of the sub-continent’s most prized materials not just for centuries but for millennia. Its position as the finest and most desirable form of woven cotton has long been established. It has been prized as far afield as classical Rome and imperial China, as well as by Mughal emperors - and their wives - closer to home. Earlier than this, muslins from Eastern and southern India were even mentioned in the Mahabharata. But it is important to remember that muslin is part of a much wider story, that of cotton itself. In this short talk, I would like to locate muslin within the Indian Subcontinent’s wider textile history, and also to discuss its role as a key fabric in India’s court culture. The early history of cotton Cotton has been the backbone of India’s textile production for about 8,000 years. Evolving from wild cotton plants, seeds and fibres of domesticated cotton have been excavated from as early as 6000BC at the site of Mehrgarh in today’s Baluchistan. Evidence of textile technology, especially finds of spindle whorls, the small circular weights used in spinning, is scattered throughout the Indus Valley sites from around the same period. The earliest known cotton thread to have been found on the subcontinent itself was excavated at the Indus Valley city of Mohenjo Daro, dating to around 2,500 BC. -

Traditional Indian Textiles Students Handbook + Practical Manual Class XII

Traditional Indian Textiles Students Handbook + Practical Manual Class XII CENTRAL BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION Shiksha Kendra, 2, Community Centre, Preet Vihar, Delhi-110301 In collaboration with National Institute of Fashion Technology Traditional Indian Textiles – Class XII Students Handbook + Practical Manual PRICE : ` FIRST EDITION : 2014 © CBSE, India COPIES : No Part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. PUBLISHED BY : The Secretary, Central Board of Secondary Education, Shiksha Kendra, 2, Community Centre, Preet Vihar, Delhi - 110301 DESIGNED & LAYOUT : M/s. India Offset Press, A-1, Mayapuri Industrial Area, Phase-1, New Delhi - 110064 Hkkjr dk lafo/kku mísf'kdk ge Hkkjr ds yksx Hkkjr dks ,d ^¿lEiw.kZ izHkqRo&laiUu lektoknh iaFkfujis{k yksdra=kRed x.kjkT;À cukus ds fy,] rFkk mlds leLr ukxfjdksa dks % lkekftd] vkfFkZd vkSj jktuSfrd U;k;] fopkj] vfHkO;fDr] fo'okl] /keZ vkSj mikluk dh Lora=rk] izfr"Bk vkSj volj dh lerk izkIr djkus ds fy, rFkk mu lc esa O;fDr dh xfjek vkSj jk"Vª dh ,drk vkSj v[k.Mrk lqfuf'pr djus okyh ca/kqrk c<+kus ds fy, n`<+ladYi gksdj viuh bl lafo/kku lHkk esa vkt rkjh[k 26 uoEcj] 1949 bZñ dks ,rn~}kjk bl lafo/kku dks vaxhÑr] vf/kfu;fer vkSj vkRekfiZr djrs gSaA 1- lafo/kku ¼c;kfyloka la'kks/ku½ vf/kfu;e] 1976 dh /kkjk 2 }kjk ¼3-1-1977½ ls ÞizHkqRo&laiUu yksdra=kRed x.kjkT;ß ds LFkku ij izfrLFkkfirA 2- lafo/kku ¼c;kfyloka la'kks/ku½ -

The Transformation of Tusser Silk

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 The Transformation of Tusser Silk Brenda M. King Orchard House, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons King, Brenda M., "The Transformation of Tusser Silk" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 459. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/459 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Transformation of Tusser Silk Brenda M. King Orchard House, Bollington Cross Macclesfield, Cheshire, SK10 5EG, UK Tel: ++ (0)1625 573928 [email protected] At the Paris Exposition of 1878 there was a display of printed and dyed Indian tusser silk. This was a striking and important display in a prestigious section of this major international exhibition. The Prince of Wales had successfully appealed to the French organisers of the Exposition, for a prominent position for the India Court. He was granted the western half of the grand transept; the position of honour among the foreign departments. The Indian Court was a series of elaborate pavilions designed by architect Casper Purdon Clark. The displays of India’s goods in the court, were thought to be far superior to those of the Great Exhibition of 1851, and were awarded many honours. The English silk dyer and printer Thomas Wardle produced the Indian tusser silk display in the British India Section of the India Court. -

Veeraa Enterprises Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Veeraa Enterprises Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India We are one of the leading manufacturers, suppliers and exporters of fancy fabrics like patchwork, pintuck and printed fabrics. These are used to make a variety of home furnishings and textile items like curtains and covers. Veeraa Enterprises Profile Established in the year 1996, we, “Veeraa Enterprises”, are a noted manufacturer, supplier and exporter of patchwork fabrics, fancy patchwork fabrics, zig zag patchwork fabrics, embroidery patchworks fabrics, blue patchwork fabrics, black patchwork fabrics, US patchwork fabrics, frill patchwork fabrics, denim frinches with applique fabrics, border embroidery applique fabrics, pintuck fabrics, embroidered pintuck fabric, denim pintuck fabrics, printed fabrics, printed patchwork fabrics, printed dobby fabrics, batik print fabrics, batik blue fabrics, kalamkari fabrics, checks fabrics, yarn dyed checks fabrics, madras checks fabrics. These are manufactured using quality raw material and are highly praised for attributes such as colorfastness, durability, ease in washing & maintaining and tear resistance. It is largely due to the quality of our fabrics that we have succeeded in putting together an esteemed group of loyal clients and attain high level of customer satisfaction. Our main business motive is to provide best fabrics at market-leading prices. Our team is aided by our sound infrastructure at all stages of production to ensure that the quality of our fabrics remains high. With the support of an able team and a good infrastructure, we have acquired a special place for ourselves in the industry of textiles and furnishings. As we fully understand the demands of our customers, they have a pleasurable experience while dealing with us. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 27:2 — Fall 2015 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Fall 2015 Textile Society of America Newsletter 27:2 — Fall 2015 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 27:2 — Fall 2015" (2015). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 71. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/71 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 27. NUMBER 2. FALL, 2015 Cover Image: Collaborative work by Pat Hickman and David Bacharach, Luminaria, 2015, steel, animal membrane, 17” x 23” x 21”, photo by George Potanovic, Jr. page 27 Fall 2015 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Ellyane Hutchinson (Website Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) and Vita Plume (Vice President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives. -

Contamination: with an Employee Picking Lint from 3 to 5 Bales and Feeding It Into the Blending and Carding Machines

PHYSIOLOGY TODAY Newsletter of the Cotton Physiology Education Program — NATIONAL COTTON COUNCIL October 1990, Volume 2, Number 1 Contamination: with an employee picking lint from 3 to 5 bales and feeding it into the blending and carding machines. If An Industrywide Issue a piece of twine or cloth appeared in the bale, he Doug Herber, Bill Mayfield, Chess would pull it out. Howard and Bill Lalor Modem machinery has replaced these workers, with robotics and automated systems now doing Over the last year, Cotton Physiology Today has cov the work. The modem opening and blending proc ered man~ topics relatin~ to p1ant growth and man agement. Economic healTh requires more than just ess automatically feeds multiple bale laydowns.lf efficient production; it also requires efficient and contaminants exist, this automated, large-scale sys profitabTe marketing. Because of the fnreat from con tem can blend them from one bale with lint from tamination to U.S. cotton's reputation and recent many other bales. Take, for example, one contami gains in market share both at home and abroad, this nated bale that goes undetected and is blended with Issue focuses on contamination, why it should be 29 contamination-free bales in a laydown. When avoiaed and how. three of these laydowns are then blended together, History of Cotton Pricing the potential exists for 45,000 pounds of contami Historically, the price of cotton has been based nated cotton. Again if undetected, yams manufac largely on reputation. Before government classing, tured from these contaminated cottons may be each growing region had a reputation for producing blended with contamination-free yams to produce a certain fiber types (S.E. -

JTA Magazine March-April 21.Cdr

The Textile Association (India) completes its 82 glorious years on April 09, 2021, which was established on April 9, 1939, TAI today is the leading and one of the largest national bodies, of textile professionals, striving for the growth of India's largest industry. The association has more than 25,000 strong members through its 26 affiliated Units (chapters), spread throughout the length and breadth of the country. Heartiest congratulations to the Founders, Trustees, Predecessor Presidents, Governing Council Members, all our esteemed members and sincere thanks for the whole hearted support to the entire textile industry extended over all these years. With emphasis and commitment to professional ethics and social responsibilities, our renewed vision is to be internationally renowned as a leading association of textile technocrats and professionals promoting scientific and technological knowledge and training with benchmarking performance. We are happy to announce that Journal of the Textile Association (JTA) is also completes its 81 years in publication. JTA is a prestigious bi-monthly peer-reviewed Journal which is also available in a digital version online on TAI's website www.textileassociationindia.org. Due to Corona pandemic, we are unable to celebrate, but both will be celebrate in physically gathering, after this pandemic is over. We wish to make TAI more connected with the industry through various ground activities organised by different Units across the country. One such initiative started interacting through JTA. We welcome more and more industry engagement through JTA. TAI's annual conferences are a prestigious annual events, being organised since last 76 years. These conferences have focused on contemporary and innovative topics with high profile speakers.