Burrows and Burrs: a Perceptual History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

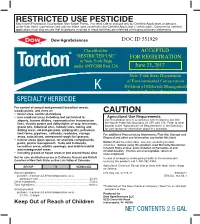

Caution Restricted Use Pesticide

RESTRICTED USE PESTICIDE May Injure (Phytotoxic) Susceptible, Non-Target Plants. For retail sale to and use only by Certified Applicators or persons under their direct supervision and only for those uses covered by the Certified Applicator's certification. Commercial certified applicators must also ensure that all persons involved in these activities are informed of the precautionary statements. DOC ID 551929 June 23, 2017 For control of annual and perennial broadleaf weeds, woody plants, and vines on CAUTION • forest sites, conifer plantations • non-cropland areas including, but not limited to, Agricultural Use Requirements airports, barrow ditches, communication transmission Use this product only in accordance with its labeling and with lines, electric power and utility rights-of-way, fencerows, the Worker Protection Standard, 40 CFR part 170. Refer to label gravel pits, industrial sites, military sites, mining and booklet under "Agricultural Use Requirements" in the Directions drilling areas, oil and gas pads, parking lots, petroleum for Use section for information about this standard. tank farms, pipelines, railroads, roadsides, storage For additional Precautionary Statements, First Aid, Storage and areas, substations, unimproved rough turf grasses, Disposal and other use information see inside this label. • natural areas (open space), for example campgrounds, parks, prairie management, trails and trailheads, Notice: Read the entire label. Use only according to label recreation areas, wildlife openings, and wildlife habitat directions. Before using this product, read Warranty Disclaimer, Inherent Risks of Use, and Limitation of Remedies at end and management areas of label booklet. If terms are unacceptable, return at • including grazed or hayed areas in and around these sites once unopened. -

Weed Risk Assessment: Centaurea Calcitrapa

Weed Risk Assessment: Centaurea calcitrapa 1. Plant Details Taxonomy: Centaurea calcitrapa L. Family Asteraceae. Common names: star thistle, purple star thistle, red star thistle. Origins: Native to Europe (Hungary, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Russian Federation, Ukraine, Albania, Greece, Italy, Romania, Yugoslavia, France, Portugal, Spain), Macaronesia (Canary Islands, Madeira Islands), temperate Asia (Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey) and North Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia) (GRIN database). Naturalised Distribution: Naturalised in New Zealand, South Africa, Central America, South America, the United States of America (eg. naturalised in 14 states, mostly in northwest including California, Idaho, Washington, Wyoming, New Mexico, Oregon, Arizona) (USDA plants database), and Australia (GRIN database). Description: C. calcitrapa is an erect, bushy and spiny biannual herb that is sometimes behaves as an annual or short-lived perennial. It grows to 1 m tall. Young stems and leaves have fine, cobweb-like hairs that fall off over time. Older stems are much-branched, straggly, woody, sparsely hairy, without wings or spines and whitish to pale green. Lower leaves are deeply divided while upper leaves are generally narrow and undivided. Rosette leaves are deeply divided and older rosettes have a circle of spines in the centre. This is the initial, infertile, flower head. Numerous flowers are produced on the true flowering stem and vary from lavender to a deep purple colour. Bracts end in a sharp, rigid white to yellow spines. Seed is straw coloured and blotched with dark brown spots. The pappus is reduced or absent. Bristles are absent. Seeds are 3-4mm long, smooth and ovoid. The root is a fleshy taproot (Parsons and Cuthbertson, 2001) (Moser, L. -

Thistle Identification Referee 2017

Thistle Identification Referee 2017 Welcome to the Thistle Identification Referee. The purpose of the referee is to review morphological characters that are useful for identification of thistle and knapweed fruits, as well as review useful resources for making decisions on identification and classification of species as noxious weed seeds. Using the Identification Guide for Some Common and Noxious Thistle and Knapweed Fruits (Meyer 2017) and other references of your choosing, please answer the questions below (most are multiple choice). Use the last page of this document as your answer sheet for the questions. Please send your answer sheet to Deborah Meyer via email ([email protected]) by May 26, 2017. Be sure to fill in your name, lab name, and email address on the answer sheet to receive CE credit. 1. In the Asteraceae, the pappus represents this floral structure: a. Modified stigma b. Modified corolla c. Modified calyx d. Modified perianth 2. Which of the following species has an epappose fruit? a. Centaurea calcitrapa b. Cirsium vulgare c. Onopordum acaulon d. Cynara cardunculus 3. Which of the following genera has a pappus comprised of plumose bristles? a. Centaurea b. Carduus c. Silybum d. Cirsium 4. Which of the following species has the largest fruits? a. Cirsium arvense b. Cirsium japonicum c. Cirsium undulatum d. Cirsium vulgare 5. Which of the following species has a pappus that hides the style base? a. Volutaria muricata b. Mantisalca salmantica c. Centaurea solstitialis d. Crupina vulgaris 6. Which of the following species is classified as a noxious weed seed somewhere in the United States? a. -

State Weed List

Class A Weeds: Non-native species whose distribution ricefield bulrush Schoenoplectus hoary alyssum Berteroa incana in Washington is still limited. Preventing new infestations and mucronatus houndstongue Cynoglossum officinale eradicating existing infestations are the highest priority. sage, clary Salvia sclarea indigobush Amorpha fruticosa Eradication of all Class A plants is required by law. sage, Mediterranean Salvia aethiopis knapweed, black Centaurea nigra silverleaf nightshade Solanum elaeagnifolium knapweed, brown Centaurea jacea Class B Weeds: Non-native species presently limited to small-flowered jewelweed Impatiens parviflora portions of the State. Species are designated for required knapweed, diffuse Centaurea diffusa control in regions where they are not yet widespread. South American Limnobium laevigatum knapweed, meadow Centaurea × gerstlaueri Preventing new infestations in these areas is a high priority. spongeplant knapweed, Russian Rhaponticum repens In regions where a Class B species is already abundant, Spanish broom Spartium junceum knapweed, spotted Centaurea stoebe control is decided at the local level, with containment as the Syrian beancaper Zygophyllum fabago knotweed, Bohemian Fallopia × bohemica primary goal. Please contact your County Noxious Weed Texas blueweed Helianthus ciliaris knotweed, giant Fallopia sachalinensis Control Board to learn which species are designated for thistle, Italian Carduus pycnocephalus knotweed, Himalayan Persicaria wallichii control in your area. thistle, milk Silybum marianum knotweed, -

Purple Starthistle Centaurea Calcitrapa Reviewer Affiliation/Organization Date (Mm/Dd/Yyyy) Monika Chandler Minn Dept of Ag 08/03/15

MN NWAC Risk Common Name Latin Name Assessment Worksheet (04-2011) Purple Starthistle Centaurea calcitrapa Reviewer Affiliation/Organization Date (mm/dd/yyyy) Monika Chandler Minn Dept of Ag 08/03/15 Bo Question Answer Outcome x 1 Is the plant species or genotype non-native? Yes, it is native to southern Europe and North Africa (Roche and Go to Box 3 Roche 1990). It is primarily a biennial but can function as an annual or short-lived perennial. 3 Is the plant species, or a related species, It is a prohibited noxious weed in Arizona, California, Nevada, Go to Box 6 documented as being a problem elsewhere? Oregon and Washington (USDA, NRCS 2015) It is a temporary noxious weed on Idaho’s statewide early detection and rapid response list (www.agri.state.id.us/Categories/PlantsInsects/NoxiousWeeds/w atchlist.php). Cal-IPC category is moderate (DiTomaso et al 2007). 6 Does the plant species have the capacity to establish and survive in Minnesota? A. Is the plant, or a close relative, currently Not recorded in Minnesota although some Centaurea species are Go to Question B established in Minnesota? established in Minnesota. B. Has the plant become established in areas It is in Iowa, Illinois, Indiana and Ontario (USDA, NRCS 2015). If this species is having a climate and growing conditions It is not documented in areas as cold as Minnesota and it is not cold hardy for similar to those found in Minnesota? unknown if this species could establish in Minnesota. MN, it is not a risk Do not list at this time 7 Does the plant species have the potential to reproduce and spread in Minnesota? A. -

Centaurea Revisited: a Molecular Survey of the Jacea Group

Annals of Botany 98: 741–753, 2006 doi:10.1093/aob/mcl157, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org Centaurea Revisited: A Molecular Survey of the Jacea Group N. GARCIA-JACAS1,*, T. UYSAL 2, K. ROMASHCHENKO3,V.N.SUA´ REZ-SANTIAGO4, K. ERTUG˘ RUL2 and A. SUSANNA1 1Botanic Institute of Barcelona (CSIC-ICUB), Passeig del Migdia s.n., E-08038 Barcelona, Spain, 2Department of Biology, Faculty of Science and Art, Selcuk University, Konya, Turkey, 3Institute of Botany M. G. Kholodny, Tereshchenkovska 2, 01601 Kiev, Ukraine and 4Department of Botany, Science Faculty, University of Granada, 18071 Granada, Spain Received: 9 December 2005 Returned for revision: 11 April 2006 Accepted: 6 June 2006 Published electronically: 27 July 2006 Background and Aims The genus Centaurea has traditionally been considered to be a complicated taxon. No attempt at phylogenetic reconstruction has been made since recent revisions in circumscription, and previous reconstructions did not include a good representation of species. A new molecular survey is thus needed. Methods Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using sequences of the internal transcribed spacers (ITS) 1 and 2 and the 5.8S gene. Parsimony and Bayesian approaches were used. Key Results A close correlation between geography and the phylogenetic tree based on ITS sequences was found in all the analyses, with three main groups being resolved: (1) comprising the most widely distributed circum- Mediterranean/Eurosiberian sections; (2) the western Mediterranean sections; and (3) the eastern Mediterranean and Irano-Turanian sections. The results show that the sectional classification in current use needs major revision, with many old sections being merged into larger ones. -

New Perspectives of Purple Starthistle (Centaurea Calcitrapa) Leaf Extracts

Dimkić et al. AMB Expr (2020) 10:183 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-020-01120-5 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access New perspectives of purple starthistle (Centaurea calcitrapa) leaf extracts: phytochemical analysis, cytotoxicity and antimicrobial activity Ivica Dimkić1*† , Marija Petrović1†, Milan Gavrilović1, Uroš Gašić2, Petar Ristivojević3, Slaviša Stanković1 and Peđa Janaćković1 Abstract Ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological studies of many Centaurea species indicated their potential in folk medi- cine so far. However, investigations of diferent Centaurea calcitrapa L. extracts in terms of cytotoxicity and antimi- crobial activity against phytopathogens are generally scarce. The phenolic profle and broad antimicrobial activity (especially towards bacterial phytopathogens) of methanol (MeOH), 70% ethanol (EtOH), ethyl-acetate (EtOAc), 50% acetone (Me2CO) and dichloromethane: methanol (DCM: MeOH, 1: 1) extracts of C. calcitrapa leaves and their poten- tial toxicity on MRC-5 cell line were investigated for the frst time. A total of 55 phenolic compounds were identifed: 30 phenolic acids and their derivatives, 25 favonoid glycosides and aglycones. This is also the frst report of the pres- ence of centaureidin, jaceidin, kaempferide, nepetin, favonoid glycosides, phenolic acids and their esters in C. calci- trapa extracts. The best results were obtained with EtOAc extract with lowest MIC values expressed in µg/mL ranging from 13 to 25, while methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus was the most susceptible strain. The most susceptible phytopathogens were Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae, Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris and Agrobacte- rium tumefaciens. The highest cytotoxicity was recorded for EtOAc and Me2CO extracts with the lowest relative and absolute IC50 values between 88 and 102 µg/mL, while EtOH extract was the least toxic with predicted relative IC 50 value of 1578 µg/mL. -

Purple Starthistle Centaurea Calcitrapa Other Common Names

Purple starthistle Other common names: red starthistle USDA symbol: CECA2 Centaurea calcitrapa ODA rating: A and T Introduction: Purple starthistle is native to the Mediterranean region, southern Europe and northern Africa. It is well adapted to a range of temperature and moisture regimes. Its potential impact on agriculture, wildlife and recreation would be significant. Distribution in Oregon: In Oregon, purple starthistle was first detected in Clackamas County and this site has been monitored and treated since 1993. A 2010 survey failed to locate any surviving plants. In 2009, a new infestation was discovered in Wheeler County. The Wheeler County site is receiving annual monitoring and treatment leading to eradication. Description: Purple starthistle is actually a heavily armored knapweed species and not classified as a true thistle. It can function as an annual or biennial depending on moisture conditions. Seedlings will sprout in the fall or early spring forming spiny rosettes in May and June. Blooming continues from midsummer through fall as the plant grows 1 to 6 feet tall. To conserve moisture the plant is covered in fine hairs, with narrow linear leaves retarding moisture loss. Flower heads are purple and arrayed with straw-colored spine-like bracts over 1 inch in length. Seeds are not plumed, the distinguishing factor between this plant and Iberian starthistle. Impacts: Closely resembling Iberian starthistle, both invasive species have the ability to adapt to a variety of climactic conditions. They are extremely competitive along roadsides and in low-rainfall rangeland, as well as in higher rainfall pastures, where they displace valuable forage. The sharp spines deter grazing animals or wildlife movement and their access to forage. -

Milestone Within the Food, Feeds, Drugs Or Clothing

DOC ID 554810 December 12, 2017 • For control of annual and perennial broadleaf weeds GROUP 4 HERBICIDE including invasive and noxious weeds, certain Active Ingredient: annual grasses, and certain woody plants and Triisopropanolammonium salt of 2-pyridine vines, on: carboxylic acid, 4-amino-3,6-dichloro- ..............................40.6% • rangeland, permanent grass pastures (including Other Ingredients ...................................................................... 59.4% grasses grown for hay*), Conservation Reserve Total .........................................................................................100.0% Acid Equivalent: aminopyralid (2-pyridine carboxylic acid, Program (CRP) 4-amino-3,6-dichloro-) - 21.1% - 2 lb/gal • non-crop areas for example, airports, barrow ditches, communication transmission lines, Keep Out of Reach of Children electric power and utility rights-of-way, fencerows, gravel pits, industrial sites, military CAUTION sites, mining and drilling areas, oil and gas pads, non-irrigation ditch banks, parking lots, Agricultural Use Requirements petroleum tank farms, pipelines, roadsides, Use this product only in accordance with its labeling and with the Worker Protection Standard, 40 CFR part 170. Refer to label railroads, storage areas, dry storm water booklet under "Agricultural Use Requirements" in the "Directions retention areas, substations, unimproved rough for Use" section for information about this standard. turf grasses; and For additional Precautionary Statements, First Aid, Storage and • natural areas (open space) for example, Disposal and other use information see inside this label. campgrounds, parks, prairie management, Notice: Read the entire label. Use only according to label directions. trailheads and trails, recreation areas, wildlife Before using this product, read Warranty Disclaimer, Inherent Risks of Use, and Limitation of Remedies at end of label booklet. openings, and wildlife habitat and management If terms are unacceptable, return at once unopened. -

Purple Starthistle Fact Sheet

Purple Starthistle Fact Sheet Centaurea calcitrapa Asteraceae Family Barry Rice, sarracenia.com, Bugwood.org D. Walters and C. Southwick, Table Grape Weed DPI Victoria Disseminule ID, USDA APHIS ITP, Bugwood.org Distinguishing Features: Flowers: The flowers are purple and 0.6 to 1 inches in diameter. Twenty-five to 40 florets (small flowers) make up each flower head. Underneath the flower are spine-tipped bracts that are greenish or straw-colored. Seeds: The seeds are oblong and 2.5-3.5 mm long. They are white and often streaked with brown. Leaves: The leaves are alternate, with deeply divided lower leaves and narrow and undivided upper leaves. The leaves are five to eight inches long and have dots of resin on their surfaces. Flowering Time: The plant produces long stems in spring and early summer. It flowers from June through November. Life cycle: Purple Starthistle can live as an annual in extremely favorable conditions, but most often lives as a biennial. Impacts: ➢ Purple Starthistle can quickly displace native flora in disturbed areas due to its rapid growth and seed production. ➢ Purple Starthistle is unpalatable to grazing animals and rapidly degrades the forage quality in any infested areas. ➢ With thicker and stronger spines than its relatives, Purple Starthistle poses a threat of injury to both humans and animals moving through infested areas. K. Mosbruger, SLCO Weed Control Program Control: ➢ Small infestations of Purple Starthistle can be effectively controlled by manually pulling and disposing of plant remains. Plants should be cut at least 2 inches below the surface. ➢ There are no effective biocontrol agents currently approved for use in the US to control Purple Starthistle. -

Natural History Studies for the Preliminary Evaluation of Larinus Filiformis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) As a Prospective Biolog

POPULATION ECOLOGY Natural History Studies for the Preliminary Evaluation of Larinus filiformis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) as a Prospective Biological Control Agent of Yellow Starthistle 1 2 3 4 L. GU¨ LTEKIN, M. CRISTOFARO, C. TRONCI, AND L. SMITH Faculty of Agriculture, Plant Protection Department, Atatu¨ rk University, 25240 TR Erzurum, Turkey Environ. Entomol. 37(5): 1185Ð1199 (2008) ABSTRACT We studied the life history, geographic distribution, behavior, and ecology of Larinus filiformis Petri (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in its native range to determine whether it is worthy of further evaluation as a classical biological control agent of yellow starthistle, Centaurea solstitialis (Asteraceae: Cardueae). Larinus filiformis occurs in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Bulgaria and has been reared only from C. solstitialis. At Þeld sites in central and eastern Turkey, adults were well synchronized with the plant, being active from mid-May to late July and ovipositing in capitula (ßowerheads) of C. solstitialis from mid-June to mid-July. Larvae destroy all the seeds in a capitulum. The insect is univoltine in Turkey, and adults hibernate from mid-September to mid-May. In the spring, before adults begin ovipositing, they feed on the immature ßower buds of C. solstitialis, causing them to die. The weevil destroyed 25Ð75% of capitula at natural Þeld sites, depending on the sample date. Preliminary host speciÞcity experiments on adult feeding indicate that the weevil seems to be restricted to a relatively small number of plants within the Cardueae. Approximately 57% of larvae or pupae collected late in the summer were parasitized by hymenopterans [Bracon urinator, B. tshitsherini (Braconidae) and Exeristes roborator (Ichneumonidae), Aprostocetus sp. -

Identification of Knapweeds and Starthistles

PNW432 IDENTIFICATIONIDENTIFICATIONIDENTIFICATIONIDENTIFICATION ofofof KnapweedsKnapweedsKnapweeds andandand StarthistlesStarthistlesStarthistles ininin thethethe PacificPacificPacific NorthwestNorthwestNorthwest A Pacific Northwest Extension Publication Washington • Oregon • Idaho ByCindyTalbottRoché,M.S.,formerWashingtonStateUniversity CooperativeExtensioncoordinator,andBenF.Roché,Jr.,Ph.D.,WSU CooperativeExtensionrangemanagementspecialist,deceased. IllustratedbyCindyRoché. PNWbulletinsareavailablefromcooperativeextensionofficesincounty seatsandfromthepublicationofficesattheland-grantuniversitiesin Idaho,Oregon,andWashington.Otherbulletinsareavailablefromthe publishingstate. Washington BulletinOffice CooperativeExtension WashingtonStateUniversity P.O.Box645912 Pullman,WA99164-5912 509-335-2857or1-800-723-1763FAX509-335-3006 email:[email protected] web:http://pubs.wsu.edu Idaho AgriculturalPublications UniversityofIdaho P.O.Box442240 Moscow,Idaho83844-2240 208-885-7982FAX208-885-4648 Oregon ExtensionandStationCommunications OregonStateUniversity 422KerrAdministration Corvallis,Oregon97331-2119 541-737-2513FAX541-737-0817 email:[email protected] web:http://eesc.orst.edu Montana ExtensionPublications MontanaStateUniversity Bozeman,MT59717 406-994-3273 Usepesticideswithcare.Applythemonlytoplants,animals,orsiteslisted onthelabel.Whenmixingandapplyingpesticides,followalllabelprecau- tionstoprotectyourselfandothersaroundyou.Itisaviolationofthelaw todisregardlabeldirections.Ifpesticidesarespilledonskinorclothing, removeclothingandwashskinthoroughly.Storepesticidesintheiroriginal