2020 Luxembourg Country Report | SGI Sustainable Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spaces and Identities in Border Regions

Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Culture and Social Practice Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Politics – Media – Subjects Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Natio- nalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de © 2015 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or uti- lized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Cover illustration: misterQM / photocase.de English translation: Matthias Müller, müller translations (in collaboration with Jigme Balasidis) Typeset by Mark-Sebastian Schneider, Bielefeld Printed in Germany Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-2650-6 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-2650-0 Content 1. Exploring Constructions of Space and Identity in Border Regions (Christian Wille and Rachel Reckinger) | 9 2. Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to Borders, Spaces and Identities | 15 2.1 Establishing, Crossing and Expanding Borders (Martin Doll and Johanna M. Gelberg) | 15 2.2 Spaces: Approaches and Perspectives of Investigation (Christian Wille and Markus Hesse) | 25 2.3 Processes of (Self)Identification(Sonja Kmec and Rachel Reckinger) | 36 2.4 Methodology and Situative Interdisciplinarity (Christian Wille) | 44 2.5 References | 63 3. Space and Identity Constructions Through Institutional Practices | 73 3.1 Policies and Normalizations | 73 3.2 On the Construction of Spaces of Im-/Morality. -

Communiqué De Presse

Communiqué de presse Etude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA LUXEMBOURG 2014/2015 Les résultats de la dixième édition de l’étude « TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA » réalisée par TNS ILRES et TNS MEDIA sont désormais disponibles. Cette étude qui informe sur l’audience des médias presse, radio, télévision, cinéma, dépliants publicitaires et Internet a été commanditée par les trois grands groupes de médias du pays: Editpress SA ; IP Luxembourg/CLT-UFA et Saint-Paul Luxembourg SA. L’étude a également été soutenue par le Gouvernement luxembourgeois. Depuis sa 1ère édition conduite en 2005-2006, l’étude Plurimédia était exclusivement réalisée moyennant un sondage téléphonique assisté par ordinateur (CATI). Considérant les évolutions de la société luxembourgeoise en matière d’usage des télécommunications et d’Internet, cette dixième édition de l’enquête est basée pour partie sur des enquêtes téléphoniques, pour une autre par Internet. L’objectif étant d’élargir la base de sondage et ainsi assurer une plus grande représentativité des résultats. L’étude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA a donc été réalisée auprès d’un échantillon aléatoire de 4.103 personnes (3.011 par téléphone, 1 092 par internet), représentatif de la population résidant au Grand-duché de Luxembourg, âgée de 12 ans et plus. Alors que la mesure d’audience des titres de presse se base sur l’univers des personnes âgées de 15 ans et plus, les résultats d’audience des autres médias se réfèrent supplémentairement sur l’univers 12+. Le terrain d’enquête s’est déroulé d’octobre 2014 à fin mai 2015. Ci-après, vous trouverez quelques chiffres clés, concernant le lectorat moyen par période de parution, c’est-à-dire le lectorat par jour moyen pour les quotidiens, le lectorat par semaine moyenne pour les hebdomadaires, et ainsi de suite. -

ARNY SCHMIT (Luxembourg, 1959)

ARNY SCHMIT (Luxembourg, 1959) Arny Schmit is a storyteller, a conjurer, a traveler of time and space. From the myth of Leda to the images of an exhibitionist blogger, from the house of a serial killer to the dark landscapes of a Caspar David Friedrich, he makes us wander through a universe that tends towards the sublime. Manipulating the mimetic properties of painting while referring to the virtual era in which we live, the Luxembourgish artist likes to surprise by playing on the false pretenses. In his paintings he creates bridges between reality, fantasy and nightmare. The medieval, baroque or romantic references reveal his profound respect for the masters of the past. Extracted from a different time era, decorative motifs populate his compositions like so many childhood memories, from the floral wallpaper to the dusty Oriental carpet, through the models of embroidery. Through fragmentation, juxtaposition and collage, Arny Schmit multiplies the reading tracks and digs the strata of the image. The beauty of his women contrasts with their loneliness and sadness, the enticing colors are soiled with spurts, the shapes are torn to reveal the underlying, the reverse side of the coin, the unknown. 1 EXHIBITION – DECEMBER 1st, 2018 to FEBRUARY 28th, 2019 ARNY SCHMIT – WILD 13 windows with a view on the wilderness. Recent works by Luxembourgish painter Arny Schmit depict his vision of a daunting and nurturing nature and its relationship with the female body. A body that Schmit likes to fragment by imprisoning it into frames of analysis, each frame a clue into a mysterious narrative, a suggestion, an impression. -

51% 49% 71% 16% 16%

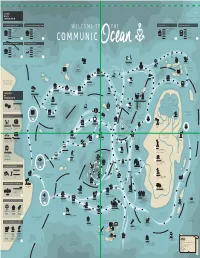

THE WAY WE USE MERKUR - INF OGRAPHIC - C OMMUNICOCEAN - MA Y/JUNE 2015 COMMUNICATION USE OF DAILY NEWSPAPERS (TOP 5) USE OF WEEKLY & BI MONTHLY MAGAZINES (TOP 5) USE OF TV-STATIONS USE OF WEB-SITES (TOP 5) 39,0% LUXEMBURGER WORT 32,8% AUTOTOURING 25,2% RTL TELE LETZEBUERG 25,7% RTL.LU 29,5% L´ESSENTIEL 14,3% AUTO REVUE 3,8% NORDLIICHT TV 16,9% WORT.LU 9,3% TAGEBLATT 13,9% AUTOMOTO 2,1% CHAMBER TV 11,3% L´ESSENTIEL.LU 5,7% LE QUOTIDIEN 11,3% PAPERJAM ... ... 9,2% PUBLIC.LU 2,1% LETZEBUERGER JOURNAL 9,6% CITY MAG ... ... 4,7% TAGEBLATT.LU USE OF MONTHLY MAGAZINES (TOP 5) USE OF RADIO-SATIONS (TOP 5) 23,0% TÉLÉCRAN 36,8% RTL RADIO LETZEBUERG 17,0% LUX-POST WEEK-END 19,6% ELDORADIO 15,7% REVUE 8,5% RTL (GERMAN LANGUAGE) 12,1% CONTACTO 5,4% RADIO LATINA 7,7% LUXBAZAR 4,5% RADIO 100,7 NEW IDEA PRINT MEDIA STORY TELLING 2010s - PRINT NATIVE IN DANGER ADVERTISING MESSENGERS SEA OF PRINT CREATIVITY TRENDY COAST TEXTUAL C ONTENT FRESH IDEAS ISLANDS BUSINESS PLAN FREE NEW SPAPER INFOGRAPHICS 2007 - 1st ISSUE OF L’ESSENTIEL BIG BUDGET FEE / DUTY MAGAZINE MESSENGERS DATA 1932 - 1st MA GAZINE VISUALIZATION CONTINENT AUTOTOURING BY CONSEIL DE AUTOMOBILE CLUB PRESSE M PICTURES A NEWSPAPER I 1848 - 1st ISSUE OF N PRINTING NEWSPAPER RACING PIGE ON LUXEMBURGER WORT S THE HISTORY 1900s - 1st ME CHANIC 1913 - 1st ISSUE 776 B.C. - WINNER LIST COMPUTER PRINTER OF TAGEBLATT LOW BUDGET T OF OF OLYMPIC GAMES SENT R COMMUNICATION BY DOVES E AGE A LANGUAGE B ARRIER REEF NATIO- M NALITY 70,5% LUXEMBOURGISH N E W S P A P E R 55,7% FRENCH GENDER PROF- A REVOLUTION BEGAN 1650 - 1st DAILY 30,6% GERMAN ESSION AS MANKIND STARTED NEWSPAPER 21,0% ENGLISH TO BIND MESSAGES 20,0% PORTUGUESE TO TIME & TO SPACE BIG BUDGET CONSEIL DE HOBBIES PUBLICITÉ INCOME EDU- CLIENTS FUN CATION COAST HOW DID THEY DO THIS ? PRINT R OUTE REPRODUCTION CLIENTS 1450 - GUTENBER G EMOTIONS BUDGET INVENTS PRINT LETTERS COAST CONFUSION TELEVISION TRIANGLE TIME BINDING DEFINITION 1970 - ST ART OF TV-SPOT VISUAL 30.000 B.C. -

Rédacteurs En Chef De La Presse Luxembourgeoise 93

Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Agenda Plurionet Frank THINNES boulevard Royal 51 L-2449 Luxembourg +352 46 49 46-1 [email protected] www.plurio.net agendalux.lu BP 1001 L-1010 Luxembourg +352 42 82 82-32 [email protected] www.agendalux.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Hebdomadaires d'Lëtzeburger Land M. Romain HILGERT BP 2083 L-1020 Luxembourg +352 48 57 57-1 [email protected] www.land.lu Woxx M. Richard GRAF avenue de la Liberté 51 L-1931 Luxembourg +352 29 79 99-0 [email protected] www.woxx.lu Contacto M. José Luis CORREIA rue Christophe Plantin 2 L-2988 Luxembourg +352 4993-315 [email protected] www.contacto.lu Télécran M. Claude FRANCOIS BP 1008 L-1010 Luxembourg +352 4993-500 [email protected] www.telecran.lu Revue M. Laurent GRAAFF rue Dicks 2 L-1417 Luxembourg +352 49 81 81-1 [email protected] www.revue.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Correio Mme Alexandra SERRANO ARAUJO rue Emile Mark 51 L-4620 DIfferdange +352 444433-1 [email protected] www.correio.lu Le Jeudi M. Jacques HILLION rue du Canal 44 L-4050 Esch-sur-Alzette +352 22 05 50 [email protected] www.le-jeudi.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Quotidiens Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek M. Ali RUCKERT - MEISER rue Zénon Bernard 3 L-4030 Esch-sur-Alzette +352 446066-1 [email protected] www.zlv.lu Le Quotidien M. -

6. Images and Identities

6. Images and Identities Wilhelm Amann, Viviane Bourg, Paul Dell, Fabienne Lentz, Paul Di Felice, Sebastian Reddeker 6.1 IMAGES OF NATIONS AS ‘INTERDISCOURSES’. PRELIMINARY THEORETICAL REFLECTIONS ON THE RELATION OF ‘IMAGES AND IDENTITIES’: THE CASE OF LUXEMBOURG The common theoretical framework for the analysis of different manifestations of ‘images and identities’ in the socio-cultural region of Luxembourg is provided by the so-called interdiscourse analysis (Gerhard/Link/Parr 2004: 293-295). It is regarded as an advancement and modification of the discourse analysis developed by Michel Foucault and, as an applied discourse theory, its main aim is to establish a relationship between practice and empiricism. While the discourses analysed by Foucault were, to a great extent, about formations of positive knowledge and institutionalised sciences (law, medicine, human sciences etc.), the interdiscourse analysis is interested in discourse complexes which are precisely not limited by specialisation, but that embrace a more comprehensive field and can therefore be described as ‘interdiscursive’ (Parr 2009). The significance of such interdiscourses arises from the general tension between the increasing differentiation of modern knowledge and the growing disorientation of modern subjects. In this sense, ‘Luxembourg’ can be described as a highly complex entity made up of special forms of organisation, e.g. law, the economy, politics or also the health service. Here, each of these sectors, as a rule, develops very specified styles of discourse restricted to the respective field, with the result that communication about problems and important topics even between these sectors is seriously impeded and, more importantly, that the everyday world and the everyday knowledge of the subjects is hardly ever reached or affected. -

RADIO LATINA | POINTS FORTS • La Radio De La Communauté Lusophone

2018 RADIO RADIO LATINA | POINTS FORTS • La radio de la communauté lusophone. • 54 000 auditeurs dont 38 300 Portugais (TNS Ilres Plurimedia 2017.II, univers résidents 12+). • Audience totale de 75 800 auditeurs (TNS Ilres Plurimedia 2017.II, univers résidents 12+). • Une audience jeune, active et familiale. Formats classiques Du lundi Tranche Tranche Tranche Tranche Tranche au dimanche tarifaire 1 tarifaire 2 tarifaire 3 tarifaire 4 tarifaire 5 7h00-9h00 6h30-7h00 6h00-6h30 12h00-14h00 22h00-6h00 Tranche horaire 9h00-12h00 14h00-16h30 16h30-19h00 19h00-22h00 Tarif 30" 90 € 75 € 60 € 45 € 22 € Modulations pour emplacement de rigueur (1re ou dernière position d’écran) : +20% | Citations d’autres marques ou entreprises : +15% Barême de tarification – durée Message de 5” 10” 15” 20” 25” 30” 35” 40” 45” 50” 55” 60” Barême 50% 60% 70% 90% 95% 100% 115% 130% 150% 160% 170% 180% Packages : Nouveaux packs ciblés et adaptés aux besoins de communication des annonceurs. EXPERIENCE LATINA Bienvenue et découverte sur 5 jours Lundi Mardi Mercredi Jeudi Vendredi 1x 6h30-7h00 1x 6h30-7h00 2x 7h00-9h00 2x 7h00-9h00 1x 6h30-7h00 1x 7h00-9h00 1x 7h00-9h00 1x 12h00-14h00 1x 12h00-14h00 2x 7h00-9h00 1x 12h00-14h00 1x 12h00-14h00 2x 16h30-19h00 1x 14h00-16h30 1x 12h00-14h00 5 jours Lundi - vendredi Lundi 2x 16h30-19h00 1x 14h00-16h30 1x 16h30-19h00 1x 16h30-19h00 1x 16h30-19h00 5 5 5 5 5 25 spots 15 secondes : 890 € Prix Package IMPACT LATINA 3 jours intensifs pour que votre action soit incontournable Coup Jour 1 Jour 2 Jour 3 de poing 1x 6h30-7h00 1x 6h30-7h00 -

Bio Paul Kirps (ENG)

Paul Kir ps 1969 born in Luxembourg, (L) Professional experiences Studies 2003 1991- 1996 • Founding the Paul Kirps / atelier de création graphique. • Écal / école cantonale d’art de lausanne , (CH) Luxembourg, (L) diploma in visual communicatio n/esaa. Commissions and personnel projects in the field of art, illustration and graphic-design. 1990- 1991 • Bts / animation. 2001-2002 • expo.02 1981- 1990 Exposition nationale suisse • Ltam / lycée technique des arts et métiers , (L) art director at the publication center. high-school diploma (option: graphic-design) Neuchâtel, (CH) 2001 • qua-lab Participation at the founding of a visual laboratory which was focused solely on non commercial and experimental design projects. Barcelona, (SP) 2000 -2001 • qua-design Graphic designer at QuA, brand environment design studio. Amsterdam, (NL) 1998 -2000 • koeweide n/postma design Collaboration with Jacques Koeweiden and Paul Postma. Amsterdam, (NL) 1996 -1997 • buero-X Graphic designer at buero-x design studio. Vienna, (A) 1/6 Paul Kir ps Exhibitions (selection) 20 11 2007 • “talk to me” •“graphythm” Group exhibition Group exhibition MoM A/ Museum of Modern Art Rotondes 2 - Luxembourg et Grande Région, New York, (USA) Capitale Européenne de la Culture. Luxembourg, (L) 2010 •“ceci n’est pas un casino” •“kms” Group exhibition Collective exhibition Villa Merkel Halle Verrière Esslingen am Neckar, (D) Meisenthal, (F) & Casino Luxembourg - Forum d'art contemporain 2006 Luxembourg, (L) •“luff 06” Video Projection •“glow in the dark” Underground Film and Music Festival Solo exhibition Lausanne, (CH) Aica / Mpk Pavillon Luxembourg, (L) •“eldorado” Group exhibition 2009 Muda m/ Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean •“prix d'art robert schuman” Luxembourg, (L) Group exhibition Galerie de l'Esplanad e/ESAMM •“pa l/secam” Metz, (F) Solo exhibition Luxembourg, (L) •“t_tris ” Group exhibition 2005 B.P.S. -

Les Journaux Au Luxembourg 1704-2004

LES JOURNAUX AU LUXEMBOURG ROMAIN HILGERT 1704-2004 SERVICE INFORMATION ET PRESSE LES JOURNAUX AU LUXEMBOURG ROMAIN HILGERT 1704-2004 SERVICE INFORMATION ET PRESSE LES JOURNAUX AU LUXEMBOURG 1704-2004 AUTEUR Romain Hilgert ÉDITEUR Service information et presse du gouvernement luxembourgeois PHOTO DE COUVERTURE Marcel Strainchamps (BNL) PHOTOS Marcel Strainchamps (BNL) ainsi que CHAN, Paris Editpress Luxembourg Imprimerie Centrale Christian Mosar Saint-Paul Luxembourg Trash Picture Company et l’auteur CONCEPT ET LAYOUT Vidale-Gloesener IMPRESSION Imprimerie Centrale © DÉCEMBRE 2004 ISBN 2-87999-136-6 LES JOURNAUX AU LUXEMBOURG 1704-2004 SOMMAIRE 002 Les journaux au Luxembourg Introduction 010 Le marché de l’exportation 1704-1795 028 Les débuts d’un débat politique 1795-1815 038 La naissance de la presse libérale 1815-1848 058 La victoire de la liberté de la presse 1848 074 Les journaux ministériels 1848-1865 102 L’âge d’or 1866-1888 136 La spécialisation 1888-1914 172 La radicalisation 1914-1940 196 Journaux nazis et clandestins 1940-1944 204 La stabilité de la presse de parti 1945-1974 222 Consensus et commerce 1975-2004 246 Bibliographie 254 Liste des titres LES JOURNAUX AU LUXEMBOURG 2 3 La presse est un important outil de la démocratie. l’Europe ou recuëil historique & politique sur les matieres Les premiers journaux luxembourgeois offraient dès le du tems, par le journaliste français Claude Jordan et l’im- XVIIIe siècle des informations qui aidaient les rares primeur et éditeur André Chevalier, originaire de France, lecteurs locaux à se faire une idée du monde qui les bien au-delà de 400 journaux et magazines ont été créés entourait. -

Die Situation in Luxemburg

Medien März 2019 13 Praktika und Stipendien an. Bitch präsentiert sich Da eine verstärkte Präsenz von Frauen in den folgendermaßen: „Bitch seeks to be a fresh, revitali- Medien als Nebeneffekt auch zu einer größere zing voice in contemporary feminism, one that wel- Beachtung von weiteren Minderheiten führen kann, comes complex arguments and refuses to ignore the ist es nicht abwegig, sich auf noch mehr Diversität contradictory and often uncomfortable realities of in den Redaktionen und den Medieninhalten zu life in an unequivocally gendered world.“ Der Titel freuen. Wenn diese die ganze Vielfalt und Pluralität mag anstoßen, wird jedoch so erklärt: „While we’re der Gesellschaft, auch über Gender-Grenzen hinaus, aware that the magazine’s title, and the organization’s widerspiegeln, wird das Risiko von Stereotypisierung name, is off-putting to some people, we think it’s und Monotonie in der Themensetzung, Bildauswahl worth it. When it’s being used as an insult, “bitch” is und Sprache vermindert. Und das tut letztendlich an epithet hurled at women who speak their minds, sowohl dem Journalismus wie auch dem gesellschaft- who have opinions and don’t shy away from expres- lichen Zusammenhalt gut. sing them, and who don’t sit by and smile uncom- fortably if they’re bothered or offended. If being an 1 http://www.frauenzählen.de 5 https://newsmavens.com outspoken woman means being a bitch, we’ll take 2 „Audiovisuelle Diversität? 6 http://fullerproject.org Geschlechterdarstellungen in Film und 7 https://www.chai-khana.org that as a compliment.“ Fernsehen in Deutschland“ (2017). https:// www.imf.uni-rostock.de/forschung/ 8 https://information.tv5monde.com/ „The future is furious“, steht auf über den Bitchmart kommunikations-und-medienwissenschaft/ terriennes audiovisuelle-diversitaet/ verkauften Bleistiften. -

L'étude TNS-Ilres Plurimédia Luxembourg 2012/2013

Communiqué de presse Etude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA LUXEMBOURG 2012/2013 Les résultats de la huitième édition de l’étude « TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA » réalisée par TNS ILRES et TNS MEDIA sont désormais disponibles. Cette étude qui informe sur l’audience des médias presse, radio, télévision, cinéma, dépliants publicitaires et Internet a été commanditée par les trois grands groupes de médias du pays: Editpress SA ; IP Luxembourg/CLT-UFA et Saint-Paul Luxembourg SA. L’étude a également été soutenue par le Gouvernement luxembourgeois. L’étude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA a été réalisée par téléphone auprès d’un échantillon aléatoire de 3.044 personnes, représentatif de la population résidant au Grand-duché de Luxembourg, âgée de 12 ans et plus. Alors que la mesure d’audience des titres de presse se base sur l’univers des personnes âgées de 15 ans et plus, les résultats d’audience des autres médias se réfèrent supplémentairement sur l’univers 12+. Le terrain d’enquête s’est déroulé de septembre 2012 à mai 2013. Ci-après, vous trouverez quelques chiffres clés, concernant le lectorat moyen par période de parution, c’est-à-dire le lectorat par jour moyen pour les quotidiens, le lectorat par semaine moyenne pour les hebdomadaires, et ainsi de suite. Pour les médias audiovisuels les chiffres indiquent généralement l’audience par jour moyen, sauf pour le cinéma et les chaînes de télévision à diffusion spécifique où la période de référence est d’une semaine. Les résultats de l’étude obtenus auprès de l’échantillon aléatoire d’individus sont extrapolés à l’ensemble de la population de résidents au Luxembourg. -

Intersex Genital Mutilations Human Rights Violations of Children with Variations of Reproductive Anatomy

Intersex Genital Mutilations Human Rights Violations Of Children With Variations Of Reproductive Anatomy NGO Report (for LOI) to the 4th Report of Luxembourg on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR) Compiled by: Intersex & Transgender Luxembourg (ITGL) a.s.b.l. (Local NGO) Dr Erik Schneider Association Intersex & Transgender Luxembourg a.s.b.l. BP 2128 L-1021 Luxembourg tgluxembourg_at_gmail.com https://itgl.lu/ StopIGM.org / Zwischengeschlecht.org (International Intersex Human Rights NGO) Markus Bauer, Daniela Truffer Zwischengeschlecht.org P.O.Box 2122 CH-8031 Zurich info_at_zwischengeschlecht.org https://Zwischengeschlecht.org/ https://StopIGM.org/ August 2020 This NGO Report online: https://intersex.shadowreport.org/public/2020-CCPR-Luxembourg-LOI-Intersex-ITGL-StopIGM.pdf 2 NGO Report (for LOI) to the 4th Report of Luxembourg on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR) Table of Contents IGM Practices in Luxembourg (p. 5-18) Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 4 Suggested Questions for the List of Issues ................................. 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 6 1. Luxembourg: Intersex Human Rights and State Report ............................................................. 6 2. About the Rapporteurs ...............................................................................................................