Reviews Marvels & Tales Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Much Amiss at Venice Airport NEWS EDITOR Location: Various Parcels

Our View 6A Subway set 8A Mercury recall 10A Jail (site) break … for Laurel interchange Businesses pay attention Adopt a pet Looking VENICE • for a “furever” home stm , 1B LOCAL NEWS COVER TO COVER AWARD-WINNING WEEKLY NEWSPAPER 50 CENTS VOLUME 64 NUMBER 34 WEDNESDAY-FRIDAY EDITION, AUG. 19-21, 2009 AN EDITION OF THE SUN FAA Land Use Audit Leases under fire BY GREG GILES pensation to the airport fund. Much amiss at Venice airport NEWS EDITOR Location: Various parcels. An FAA land use audit dated BY GREG GILES Aug. 10 reviewed deeds, leases NEWS EDITOR and other documents dating back to the original Venice Municipal Airport quitclaim As if the city of Venice didn’t deed in 1947. The audit found have enough on its plate with a a number of irregularities that formal Part 16 complaint unless corrected could subject pending with the Federal the city to civil penalties over Aviation Administration, now the following leases: the FAA has released results of The Pier Group/Sharky’s Rest- a special audit of the Venice aurant — Numerous concerns airport, and the news is any- with a new lease, including thing but good. escalation/rental rates and The city made public the skimpy revenues (only one- FAA land use audit on Tuesday. third goes to the airport fund). It has far reaching implications City must revoke, modify or for the Venice Municipal amend the terms. Airport — further solidifying Location: One-acre parcel the FAA’s long-held position off Harbor Drive on the beach that Lake Venice Golf Club’s SUN PHOTO BY GREG GILES SUN PHOTOS BY GREG GILES abutting the Venice Municipal driving range is in a safety Fishing Pier. -

Bay Guardian | August 26 - September 1, 2009 ■

I Newsom screwed the city to promote his campaign for governor^ How hackers outwitted SF’s smart parking meters Pi2 fHB _ _ \i, . EDITORIALS 5 NEWS + CULTURE 8 PICKS 14 MUSIC 22 STAGE 40 FOOD + DRINK 45 LETTERS 5 GREEN CITY 13 FALL ARTS PREVIEW 16 VISUAL ART 38 LIT 44 FILM 48 1 I ‘ VOflj On wireless INTRODUCING THE BLACKBERRY TOUR BLACKBERRY RUNS BETTER ON AMERICA'S LARGEST, MOST RELIABLE 3G NETWORK. More reliable 3G coverage at home and on the go More dependable downloads on hundreds of apps More access to email and full HTML Web around the globe New from Verizon Wireless BlackBerryTour • Brilliant hi-res screen $ " • Ultra fast processor 199 $299.99 2-yr. price - $100 mail-in rebate • Global voice and data capabilities debit card. Requires new 2-yr. activation on a voice plan with email feature, or email plan. • Best camera on a full keyboard BlackBerry—3.2 megapixels DOUBLE YOUR BLACKBERRY: BlackBerry Storm™ Now just BUY ANY, GET ONE FREE! $99.99 Free phone 2-yr. price must be of equal or lesser value. All 2-yr. prices: Storm: $199.99 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. Curve: $149.99 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. Pearl Flip: $179.99 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. Add'l phone $100 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. All smartphones require new 2-yr. activation on a voice plan with email feature, or email plan. While supplies last. SWITCH TO AMERICA S LARGEST, MOST RELIABLE 3G NETWORK. Call 1.800.2JOIN.IN Click verizonwireless.com Visit any Communications Store to shop or find a store near you Activation fee/line: $35 ($25 for secondary Family SharePlan’ lines w/ 2-yr. -

Cineclubuned 24.Pdf

Asociación Cultural UNED SORIA Presidente Saturio Ugarte Martínez Vicepresidente Carmelo García Sánchez Secretario José Jiménez Sanz Tesorero Cristina Granado Bombín Vocales Mª Desirée Moreno Pérez Anselmo García Martín Jesús Labanda Izquierdo Dario García Palacios Coordinador Carmelo García Sánchez 24 Secciones Pantalla Grande Curso Programación y Textos Roberto González Miguel (RGM) 2017.2018 José María Arroyo Oliveros (JMA) Julián de la Llana del Río (JLLR) Ángel García Romero (AGR) Miradas de Cine Programación y Textos Roberto González Miguel (RGM) José María Arroyo Oliveros (JMA) Edita Soria de Cine Asociación Cultural UNED. Soria Selección y Textos Julián de la Llana del Río (JLLR) D.L. So-159/1994 Cineclub UNED c/ San Juan de Rabanera, 1. 42002 Soria. t. 975 224 411 f. 975 224 491 Colaboradores [email protected] www.cineclubuned.es Colaboración especial Susana Soria Ramas Pedro E. Delgado Cavilla © Fotografías: Alberto Caballero García Cabeceras: Unsplash (diferentes autores) Peliculas: Distribuidoras Producción Audiovisual Visorvideo. Victor Cid (www.visorvideo.tv) Diseño Gráfico/Maqueta Roberto Peña (www.elprincipiokiss.es) Impresión Arte Print Otras colaboraciones José Reyes Salas de proyección Centro Cultural Palacio de la Audiencia (Plaza Mayor) Casa de la Tierra- UNED. (c/ San Juan de Rabanera, 1). 24 OCTUBRE NOVIEMBRE DICIEMBRE ENERO i Lu Ma M Ju Vi Sa Do i Lu Ma M Ju Vi Sa Do i Lu Ma M Ju Vi Sa Do i Lu Ma M Ju Vi Sa Do 01 01 02 03 04 05 01 02 03 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 04 05 06 07 -

Inspirációm: Japán Kultúra És Hagyomány Tükröződése a Japán Gyerekkönyvekben És Játékokban

Nagy Diána Inspirációm: Japán Kultúra és hagyomány tükröződése a japán gyerekkönyvekben és játékokban Doktori Értekezés Témavezető: Molnár Gyula MOME Doktori Iskola Budapest, 2013 Tartalomjegyzék Japán játékok a 20� század előtt �����������������������������������������������������������48 Babák �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 50 Bevezetés ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 Állatok és egyéb játékok �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 51 Japán adottságai, rövid földrajzi áttekintése ����������������������������������������������7 Trükkös játékok ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 52 Japán rövid történelmi áttekintése �������������������������������������������������������������7 Kerekeken guruló játékok ������������������������������������������������������������������������� 52 Rövid művészettörténeti áttekintés �������������������������������������������������������������8 Csoportosan játszható játékok ������������������������������������������������������������������ 53 Japán kerámiaművesség és szobrászat ��������������������������������������������������������� 8 Fejlődés a játékgyártásban ��������������������������������������������������������������������56 Japán festészet és fametszés ����������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 A műanyag elterjedése Japánban és a világban ������������������������������������������� -

June 2010 Calendar

June 2010 EXHIBITS In the Main Gallery MONDAY SATURDAY SATURDAY FRIDAY MARK NEWTON: SCULPTURE, June 1 7 12 19 25 GREAT BOOKS DISCUSSION GROUP: A NEXT CHAPTER: A monthly discussion PULITZER-PRIZE WINNING NEW SANDWICHED IN. Musical Manners and through 30. Story in this issue. AAC discussion of Frankenstein by Mary Shel- of current events. Join us from 10:30 a.m. YORKERS: Professor Peter West discuss- Mores of the 19th Century. Linda Pratt and In the Photography Gallery ley. 1 p.m. to noon for a lively discussion. Bring your es Eden’s Outcast by John Matteson, at this Frank Hendricks, costumed in period at- opinions! Contact Lee Fertitta at 883-4400, last session of the Reading and Discussion tire, perform a program of popular songs THE PHOTOGRAPHY CLUB OF LONG ST Ext. 135 for additional information. series. This is really a biography of the and parlor music from 19th century ISLAND: 31 ANNUAL EXHIBITION, whole Alcott family, though it narrows America, including songs such as “Wood- through June 30. For over thirty years, to a dual portrait of Louisa May and her man Spare That Tree,” “Grandfather’s club members have been exhibiting their father Bronson, after the wild success Clock,” “Oh Susanna” and “Camptown landscapes, seascapes, cityscapes, still of Little Women in 1868 gave Louisa the Races,” dance tunes of the period, and lifes, portraits, travel pictures and abstrac- independence she longed for and Bronson the shorter piano works of Schumann, tions at the library. enjoyed more modest acclaim for his book Schubert, Grobe and Gottschalk. The SUNDAY In the Community Gallery Tablets and his lecture tours. -

Hayao Miyazaki: Estilo De Un Cineasta De Animación

Universidad Católica del Uruguay Facultad de Ciencias Humanas Licenciatura en Comunicación Social Memoria de Grado HAYAO MIYAZAKI: ESTILO DE UN CINEASTA DE ANIMACIÓN María José Murialdo Tutor: Miguel Ángel Dobrich Seminario: Cine de Animación Montevideo, 2 de julio de 2012 Los autores de la memoria de grado son los únicos responsables por los contenidos de este trabajo y por las opiniones expresadas que no necesariamente son compartidas por la Universidad Católica del Uruguay. En consecuencia, serán los únicos responsables frente a eventuales reclamaciones de terceros (personas físicas o jurídicas) que refieran a la autoría de la obra y aspectos vinculados a la misma. Resumen de la Memoria de Grado La Memoria de Grado analizará las nueve películas escritas y dirigidas por Hayao Miyazaki, director de cine de animación japonés contemporáneo, para determinar si existe un estilo particular y reconocible que impregne sus obras. Para ello se hará un breve recorrido por la historia de Japón, al igual que por la historia del cine de animación, haciendo foco en el anime. También se incluirá la biografía del director y se hará un breve recorrido por la historia y las obras de Studio Ghibli desde sus comienzos, estudio de cine de animación creado en 1985 por Hayao Miyazaki e Isao Takahata –director de cine de animación nipón–. Para concluir si existe definitivamente un estilo Miyazaki se analizarán sus obras en base a los siguientes ejes de investigación: el argumento en sus películas, los recursos estilísticos empleados, y los temas y conceptos principales y recurrentes. Descriptores Miyazaki, Hayao; animé; cine animado; Japón; cine japonés. -

Did Taylor Swift Hint About Collaboration with Katy Perry And

14 WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 7, 2019 Taylor Swift, Selena Gomez and Katy Perry Matt Damon get U.S. singer Pink’s Did Taylor Swift hint daughters’ names tour crew crash about collaboration inked on arm land at Danish Los Angeles airport with Katy Perry and COPENHAGEN Selena Gomez? ollywood actor Matt HDamon just got him- private aircraft car- self inked with tattoos ded- Los Angeles A rying members of icated to his four daugh - U.S. singer Pink’s tour ters. crew crash landed at a rior to the release of ‘Lover’, Damon went to famous Danish airport early on her seventh studio album Tay- Hollywood tattoo artist Tuesday and burst into Plor Swift posted cryptic mes- named Daniel Stone for flames but all occupants sages on social media which left fans getting his arm inked with escaped unharmed, con- convinced that the track might include a delicate script. Arranged cert promoter Live Na- her longtime bestie Selena Gomez and from oldest to youngest, tion Norway said. former foe Katy Perry. the tattoo is a heart-warm- “I have been Swift shared a set of colourful friend- ing tribute to 20-year-old told that it ship bracelets on social media on Monday, Alexia, 13-year-old Isabel- was part of triggering speculation of a collaboration. la, 10-year-old Gia Pink’s team The speculations reached an all-time and 8-year-old which was high when an alleged attendee of Swift’s Stella. onboard the recent secret session (a private album lis- The fine line plane and that tening party where fans were picked by tattoos, which everybody is the star herself ) claimed that the trio of were drawn up unharmed,” Rune Lem pop star’s lent their vocals to a song about by Stone, are Matt Damon of Live Nation Norway “female empowerment.” placed close told Reuters. -

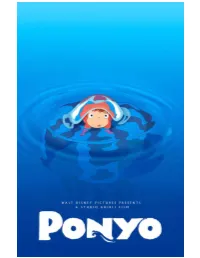

Ponyo Additional Voices

THIS MATERIAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE ONLINE AT http://www.wdsfilmpr.com Distributed by WALT DISNEY STUDIOS MOTION PICTURES © 2009 Nibariki-GNDHDDT. All Rights Reserved. disney.com/ponyo Additional Voices CARLOS ALAZRAQUI BOB BERGEN CREDITS JOHANNA BRADDY MARSHA CLARKE JOHN CYGAN JENNIFER DARLING MADISON DAVENPORT COURTNEE DRAPER CRISPIN FREEMAN JESS HARNELL ELLA DALE LEWIS SHERRY LYNN STUDIO GHIBLI DANNY MANN MONA MARSHALL NIPPON TELEVISION NETWORK MICKIE MCGOWAN LARAINE NEWMAN DENTSU COLLEEN O’SHAUGHNESSEY JAN RABSON HAKUHODO DYMP U.S. Production WALT DISNEY STUDIOS Directors. JOHN LASSETER HOME ENTERTAINMENT BRAD LEWIS MITSUBISHI PETER SOHN TOHO Executive Producers . JOHN LASSETER KATHLEEN KENNEDY Present FRANK MARSHALL English Language Screenplay . MELISSA MATHISON PONYO Translated from the Original Japanese by . JIM HUBBERT ©2008 Nibariki-GNDHDDT Associate Producers . PAUL CICHOCKI KEVIN REHER Written and Directed by . HAYAO MIYAZAKI Voice Casting. NATALIE LYON Producer . TOSHIO SUZUKI Post Production Coordinator . ERIC ZIEGLER Music . JOE HISAISHI Production Finance. MARC S. GREENBERG Imaging . ATSUSHI OKUI CHRISTOPHER “STU” STEWART Color Design . MICHIYO YASUDA Business & Legal Backgrounds. NOBORU YOSHIDA Affairs . JODY WEINBERG SILVERMAN Animation . KATSUYA KONDO Director’s Assistants . HEATHER FENG LAUREL STOUT Cast Producer’s Assistant. JIM RODERICK Sound Services Gran Mamare . CATE BLANCHETT Provided by . SKYWALKER SOUND Ponyo . NOAH CYRUS Re-Recording Mixer . MICHAEL SEMANICK Koichi . MATT DAMON ADR Supervisor . MICHAEL SILVERS Lisa . TINA FEY ADR Editor. MAC SMITH Sosuke. FRANKIE JONAS Supervising Assistant Editor. CHRIS GRIDLEY The Newscaster . KURT KNUTSSON Mix Technician . TONY SERENO Yoshie . BETTY WHITE Dialogue Recording . DOC KANE Fujimoto . LIAM NEESON BOBBY JOHANSON Kumiko . JENNESSA ROSE ANDY WRIGHT Toki. LILY TOMLIN Prints by . DELUXE LABS Noriko . CLORIS LEACHMAN 1 Studio Teachers . -

Still Buffering 167: How to Jewelry Published on May 17, 2019 Listen Here on Themcelroy.Family

Still Buffering 167: How to Jewelry Published on May 17, 2019 Listen here on themcelroy.family [theme music plays] Rileigh: Hello, and welcome to Still Buffering, a sister's guide to teens through the ages. I am Rileigh Smirl. Sydnee: I'm Sydnee McElroy. Teylor: And I'm Teylor Smirl. Sydnee: So did uh... Did you all watch Saturday Night Live this past weekend? Rileigh: Uh, there was only one part of it I cared about. Sydnee: This is why I was wondering. Uh, I still do. I think that makes me— does that make me old, that I watch Saturday Night Live every weekend? Well, I watch it the following morning— Rileigh: I was gonna say, the only other people I know that watch it are Mom and Dad, and they record it and then watch it on Sunday. Sydnee: Yup. That's exactly what I do, so... Teylor: Uh, yeah. That's a real small age divide there, because I don't watch Saturday Night Live. Rileigh: 'Cause you're saying that 11:30 is too late for you. Sydnee: It is! Rileigh: It comes on at 11:30. Sydnee: I could start— I could watch the first 30 minutes, but after midnight, I turn into a pumpkin. I'm done, man. Rileigh: [laughs] Sydnee: Emma Thompson was hosting. She's great, very funny. Rileigh: It's just... Sydnee: I wondered, though, because the musical guest, I was not aware, had come back. Had returned from when— Rileigh: The boy band grave. Sydnee: [laughs] — from, like, our teenage— your teenage.. -

Eiko Kadono 2018 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan

photo ⓒ Shimazaki Eiko Kadono 2018 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan 1 photo Ⓒ Shimazaki CONTENTS Biographical information ...................................................... 3 Statement .................................................................................... 4 Appreciative essay ................................................................... 8 Awards and other distinctions ..........................................10 Five important titles ..............................................................13 Translated editions ................................................................68 Complete bibliography ........................................................82 Full translation of Kki's Delivery Service ........................98 2 BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION Eiko Kadono Born in Tokyo in 1935. Eiko Kadono lost her mother when she was fve. Be- fore long the Pacifc War started, so she had to be evacuated to the northern side of Japan at 10 years old. The experience of war as a child is at the root of Kadono’s deep commitment to peace and hapiness. She studied American literature at Waseda University, after graduation she worked at a publisher. After marriage she accompanied her hasband to Brazil and lived in San Paulo for two years. On the long voyage to and from Brazil, she was able to broaden her knowledge about the varied countries. These experiences brought up her curious and multicultural attitude toward creative activity. Her frst book was published in 1970, since then she pub- lished about 250 books, and these were translated into 10 languages. Kadono says “to start reading a book is like opening a door to a different world. It doesn’t close at the end of the story, another door is always wait- ing there to be opened. People will start to look at the world in a different way after reading a story, and it’s the beginning in a sense. And I think that is the true pleasure of reading. -

1.1 Literatura Infantil: Pedagogia E Humanização

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIENCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS ORIENTAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LÍNGUA, LITERATURA E CULTURA JAPONESA LUCIANA FONSECA DE ARRUDA A MORTE, O VAZIO E O AMOR: UMA ANÁLISE INTERDISCIPLINAR DE O URSO E O GATO MONTÊS, DE KAZUMI YUMOTO Versão Corrigida SÃO PAULO 2018 LUCIANA FONSECA DE ARRUDA A MORTE, O VAZIO E O AMOR: UMA ANÁLISE INTERDISCIPLINAR DE O URSO E O GATO MONTÊS, DE KAZUMI YUMOTO Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de mestre em Letras. Área de Concentração: Língua, Literatura e Cultura Japonesa Orientadora: Prof. ª Dr. ª Neide Hissae Nagae Versão Corrigida SÃO PAULO 2018 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. ARRUDA, L. F. A morte, o vazio e o amor – uma análise interdisciplinar de O Urso e o Gato montês, de Kazumi Yumoto. Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de mestre em Letras. Banca Examinadora Prof.Dr.________________________Instituição:________________________ Julgamento:_____________________Assinatura:_______________________ Prof.Dr.________________________Instituição:________________________ Julgamento:_____________________Assinatura:_______________________ Prof.Dr.________________________Instituição:________________________ Julgamento:_____________________Assinatura:_______________________ Agradecimentos À Professora Doutora Neide Hissae Nagae pelo apoio e compreensão nessa jornada do mestrado. Às Professoras Doutoras Madalena Natsuko Hashimoto Cordaro e Juliana Santos Graciani pelas inestimáveis contribuições na qualificação. Ao amigo Rodrygo Tanaka por compartilhar o gosto por livros infanto- juvenis e ter me apresentado ao livro que analiso. -

Jack Cole: an Innovator Behind the Scenes Sydney Vila……………………………………81

Stellar Undergraduate Research Journal Oklahoma City University Volume 8, 2014 Stellar Oklahoma City University’s Undergraduate Research Journal This academic journal is a compilation of research that represents the many disciplines of Oklahoma City University, ranging from dance, theology, and business to film, philosophy and gender studies. This diversity makes this journal representative of all the exceptional undergraduate research at Oklahoma City University. Editor-in-Chief : Miriah Ralston Faulty Sponsor : Dr. Terry Phelps Stellar is published annually by Oklahoma City University. Opinions and beliefs herein do not necessarily reflect those of the university. Submissions are accepted from undergraduate students from all schools in the university. Please address all correspondence to: Stellar c/o The Learning Enhancement Center 2501 N. Blackwelder Ave. Oklahoma City, OK 73106 2 Contents Culpability or Chaos? Ashton Arnoldy………………….……………...5 Woman Wisdom: Child or Spirit? Allison Bevers…………………………..…….14 PaceButler Dillon Byrd……………………………………..28 How Internet Sales Tax Affects the Battle Between Best Buy and Amazon Juan Campos, Brian Jaimes, and David Bishop…...…………………………… 40 Resistance in the Works of Kierkegaard and Foucault: Is Resistance Really Possible in the 21st Century? Colin Ferguson………………………………..48 The Visible Invisibility: A Study of the Racial Paradox in Danzy Senna’s Caucasia Jason Herrera…………………………………55 No Fighting in the Sea: Ponyo on Violence in American Culture Matthew Hester and James Cooper………..64 Beauty or a Beast: A Close Examination of the Novel and Film Adaptation of Beastly Abigail Vestal………………………………..73 3 Jack Cole: An Innovator Behind the Scenes Sydney Vila……………………………………81 Femininity Brittany Yanchick……………………………..88 Credits and Thanks…………………………………………..…….97 4 Culpability or Chaos? Ashton Arnoldy After watching Safe for the first time, I left the screening in awe and frustration.