2009.0507.FLYING LESSONS.FAA Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customer Guidance for Ferry / Test Flight Handling

Customer Guidance for Ferry / Test flight Handling Customer Service Boeing Shanghai 1 COPYRIGHT © 2010 BOEING SHANGHAI AVIATION SERVICES CO., LTD. Important Notice Important Notice to Customer about Aircraft Input/output PVG procedure Please send the Landing / Departure flight application to CAAC Beijing ATC at least (Five) 5 working days in advance with all necessary information and copy to Boeing Shanghai Customer Service. Please forward the flight permit granted by CAAC ATC to Boeing Shanghai for aircraft customs clearance purpose. All flight crew on board MUST hold “C” or “F” or “M” visa. All technical crew on board MUST hold “F” or “M” visa. Boeing Shanghai can assist Customer in issuing invitation letter upon request. Please fill in the attached Form Comm 001 of Aircraft Information for CIQ declaration purpose and send it to Boeing Shanghai Customer Service at least (Five) 5 working days before the aircraft delivery. Please forward the On – Site Representatives’ passport copies, prior to their arrival, to Boeing Shanghai Customer Service for Entry Permit preparation. COPYRIGHT © 2010 BOEING SHANGHAI AVIATION SERVICES CO., LTD. Important Notice Cont’ Ramp Permit The apron outside of Boeing Shanghai hangar is secured by Shanghai Airport Security Office. Anyone wants to access to aircraft of outside hangar is requested to hold a ramp permit. To get ramp permit, it is necessary for people to have an interview in the Security Office with holding passport , non-criminal statement and company badge. Normally it takes 3 working days to get the permit. For the non- criminal statement, it should be issued by police office or government officials, and notarized by Chinese embassy / consulate; it is also acceptable if it is issued by the foreign embassy / consulate in China. -

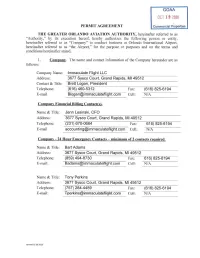

Immaculate Flight Permit Agreement

GOAA OCT 19 2020 PERMIT AGREEMENT Commercial Propert\2s THE GREATER ORLANDO AVIATION AUTHORITY, hereinafter referred to as "Authority," by its execution hereof, hereby authorizes the following person or entity, hereinafter referred to as "Company" to conduct business at Orlando International Airport, hereinafter referred to as "the Airport," for the purpose or purposes and on the terms and conditions hereinafter stated. 1. Company. The name and contact information of the Company hereunder are as follows: Company Name: Immaculate Flight LLC Address: 3677 Sysco Court, Grand Rapids, Ml 49512 Contact & Title: Brett Logan , President Telephone: (616) 460-5312 rax: (616) 825-6194 E-mail [email protected] Cell: N/A Company Financial Billing Contact(s). Name & Title: Jenn Lesinski, CFO Address: 3677 Sysco Court, Grand Rapids, Ml 49512 Telephone: (231) 670-0664 Fax: 616) 825-6194 E-mail [email protected] Cell: N/A 1 Compam - 24 Hour Emergency Contacts - minimum of 2 contacts required. Name & Title: Bart Adams Address: 3677 Sysco Court, Grand Rapids, Ml 49512 Telephone: (859) 494-8730 Fax: 616) 825-6194 E-mai l: [email protected] Cell: N//\ Name & Title: Tony Perkins Address: 3677 Sysco Court, Grand Rapids, Ml 49512 Telephone: (757) 284-4489 Fax: (616) 825-6194 E-mail: [email protected] Cell: NIA rev, sed 02.06 2020 Company Insurance Contact Name & Title: Jenn Lesinski, CFO Address: -- 36f7 Sysco·coui-(-Grand ·Raplcfa,-- MT495f2··-------------- ----- ------ Telephone: (231) 670-0664 Fax: (616) 825-6194 E-mail: [email protected] Cell: NIA Company Authorized Signature Contact Access Control (all badges and key requests') Name & Title: Brandon Brent , Central Florida Regional Sales Manager Address: 3677 Sysco Court, Grand Rapids, Ml 49512 Telephone: (407) 429-8623 Fax: (616) 825-6194 E-mail: [email protected] Cell: NIA 2. -

Airworthiness Requirements Ac S – Areas of Operation: Task B

AIRWORTHINESS REQUIREMENTS AC S – AREAS OF OPERATION: TASK B How do you prepare for a flight? PAVE: Pilot, Aircraft Environment and External Pressures. PILOT A pilot must continually make decisions about competency, condition of health, mental and emotional state, level of fatigue, and many other variables. AIRCRAFT A pilot frequently bases decisions on evaluation of the airplane, such as performance, equipment, or airworthiness. This task will concentrate on the aircraft (ASEL – Airplane Single Engine Land). ENVIRONMENT The environment encompasses many elements that are not pilot or airplane related, including such factors as weather, air traffic control (ATC), navigational aids, terrain, takeoff and landing areas and surrounding obstacles. Weather is one element that can change drastically over time and distance. EXTERNAL PRESSURES The pilot must evaluate the three previous areas to decide on the desirability of under- taking or continuing the flight as planned. It is worth asking why the flight is being made, how critical it is to maintain the schedule, and if the trip is worth the risks. P – Pilot for the Private Pilot: Start with I’M SAFE: Illness, medication, stress, alcohol (.04), fatigue (acute and chronic) and eating/emotional factors. If any of these factors apply, you should not fly. As a private pilot, you are required to carry your pilot’s certificate, medical and a government ID. As a private pilot, you are allowed to carry passengers (not for hire) – 61.113, fly when visibility is less than 3 miles (SVFR – Special VFR) and can fly without visual reference to the surface. Special requirements for the Private Pilot are: Must be a Private Pilot to take off and land within (KSFO) Class B Airspace (AIM 3-2-3) and can fly at night. -

Airport Rules & Regulations

Restated Airport Rules & Regulations Effective Date: May 4th, 2020 Hollywood Burbank Airport 2627 Hollywood Way Burbank, CA 91505 Table of Contents Chapter 1 – General ..................................................................................................... 6 1.1 General Provisions ........................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Requirement to Comply with Applicable Laws ............................................................................... 6 1.3 AOA Considered to Be Public Property with Controlled/Restricted Access .................................. 6 1.4 Emergency Powers/Authorities ....................................................................................................... 6 1.5 Definitions ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1.6 Boundaries ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 2 – Conduct .................................................................................................. 10 2.1 Damage to or Destruction of Airport Property .............................................................................. 10 2.2 Health ............................................................................................................................................. 10 2.3 Right of Inspection ........................................................................................................................ -

Airventure NOTAM

NOTAM Special Flight Procedures effective 6 AM CDT July 19 to Noon CDT July 29, 2019 For a free, printed copy of this NOTAM booklet, call EAA at 1-800-564-6322. To view or download this information, visit www.eaa.org/notam, or www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/notices. Table of Contents Preflight Planning ...................................... 1 VFR Route Planning Guide ................... 2-3 Fisk VFR Arrival to OSH ........................ 4-7 Fisk VFR Arrival Runway Paths ........... 8-11 Fond du Lac Diversion Procedure ........... 12 Oshkosh Airport Notes ............................. 13 VFR & IFR Departure from Oshkosh . 14-15 Turbine/Warbird Arrival ............................ 16 AirVenture Seaplane Base ...................... 17 Helicopter Arrival/Departure..................... 18 Ultralight Arrival/Departure ...................... 19 Fond du Lac Arrival/Departure ........... 20-21 Appleton Arrival/Departure ................ 22-23 IFR Arrival/Departure ......................... 24-27 Canadian Pilots ....................................... 28 Oshkosh No-Radio Arrival ....................... 28 Flight Service Information ........................ 29 Changes for 2019 include: New procedure for diversion to Fond du Lac Restriction on transponder use removed IFR routing changes Manitowoc (MTW) VOR decommissioned Numerous text and graphics changes This notice does not supersede restrictions contained in other FDC NOTAMs. Be sure to check current NOTAMs. Flight Procedures Effective July 19-29, 2019 Preflight Planning For one week -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 130/Monday, July 12, 2021/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 130 / Monday, July 12, 2021 / Rules and Regulations 36493 Authority for This Rulemaking (a) Effective Date (2) Before using any approved AMOC, notify your appropriate principal inspector, Title 49 of the United States Code This airworthiness directive (AD) is effective July 27, 2021. or lacking a principal inspector, the manager specifies the FAA’s authority to issue of the local flight standards district office/ rules on aviation safety. Subtitle I, (b) Affected ADs certificate holding district office. section 106, describes the authority of None. the FAA Administrator. Subtitle VII: (k) Related Information Aviation Programs describes in more (c) Applicability For more information about this AD, detail the scope of the Agency’s This AD applies to True Flight Holdings contact Fred Caplan, Aviation Safety authority. LLC Models AA–1, AA–1A, AA–1B, AA–1C, Engineer, Atlanta ACO Branch, FAA, 1701 The FAA is issuing this rulemaking and AA–5 airplanes, all serial numbers, Columbia Avenue, College Park, GA 30337; certificated in any category. phone: (404) 474–5507; fax: (404) 474–5606; under the authority described in email: [email protected]. Subtitle VII, Part A, Subpart III, Section (d) Subject (l) Material Incorporated by Reference 44701: General requirements. Under Joint Aircraft System Component (JASC) that section, Congress charges the FAA Code: 5512, Horizontal Stabilizer, Plate/Skin; (1) The Director of the Federal Register with promoting safe flight of civil 5522, Elevator, Plates/Skin Structure. approved the incorporation by reference aircraft in air commerce by prescribing (IBR) of the service information listed in this regulations for practices, methods, and (e) Unsafe Condition paragraph under 5 U.S.C. -

IATA Guidance Managing Aircraft Airworthiness During and Post

Guidance for Managing Aircraft Airworthiness for Operations During and Post Pandemic Edition 1-12 June 2020 DISCLAIMER The information contained in this publication is subject to constant review in the light of changing government requirements and regulations. No subscriber or other reader should act on the basis of any such information without referring to applicable laws and regulations and without taking appropriate professional advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the International Air Transport Association shall not be held responsible for any loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misprints or misinterpretation of the contents hereof. Furthermore, the International Air Transport Association expressly disclaims any and all liability to any person or entity, whether a purchaser of this publication or not, in respect of anything done or omitted, and the consequences of anything done or omitted, by any such person or entity in reliance on the contents of this publication. All IATA Covid19 related guidance materials can be found at https://www.iata.org/en/programs/covid-19-resources-guidelines/ For feedback, questions or comments, please contact [email protected] 1 Guidance for Managing Aircraft Airworthiness for Operations During and Post Pandemic Edition 1 – 12 June 2020 Not controlled when downloaded or printed Contents Revision record .............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Regulating Drone Use

Regulating Drone Use A CCM Government Finance & Research Department Municipal InfoKit July 2016 Regulating Drone Use A CCM Government Finance & Research Municipal InfoKit Copyright © July 2016 Connecticut Conference of Municipalities All Rights Reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any way for profit and is intended for the exclusive use of Connecticut Conference of Municipalities (CCM) Members and for the employees of its Members. This publication may not be shared, copied, or electronically stored for the use of any non-Member municipality, entity, or individual. The Connecticut Conference of Municipalities reserves the right to grant exceptions to these limitations and will do so exclusively by means of prior written consent. CCM is not responsible for any errors or omissions that may appear in this publication. This publication is intended for general reference purposes only and is not intended to provide legal advice, opinions, or conclusions. If you have questions about particular legal issues, the application of the law to specific factual situations, or the interpretation of any statutes, ordinances, or case law referenced in this publication, CCM strongly recommends that you consult your attorney, certified public accountant, or other relevant party. For more information, please contact the CCM Government Relations & Research at (203) 498-3000 or [email protected]. INTRODUCTION The recreational use of drones continues to gain popularity throughout the country. A 2015 report published by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) predicts that 1.9 million unmaned aircraft system (UAS) units, more commonly known as drones, will be purchased by “hobbyists” in the United States in 2016. -

AIRWORTHINESS CERTIFICATE and SPECIAL FLIGHT PERMIT TTCAA Advisory Circular TAC- 022E Date: 2013/09/27

TTCAA Trinidad and Tobago Civil Aviation Authority Advisory Circular Subject: AIRWORTHINESS CERTIFICATE AND SPECIAL FLIGHT PERMIT TTCAA Advisory Circular TAC- 022E Date: 2013/09/27 PURPOSE 1. (1) The purpose of this TTCAA Advisory Circular (TAC) is to provide policy and guidance associated with airworthiness certification, issue and renewal of a Trinidad and Tobago Airworthiness Certificate and issue of a Special Flight Permit. This TAC also includes information on the requirements for Flight Tests and Airworthiness approvals for export. (2) TAC-022E replaces and supersedes TAC-022D which is now cancelled and should be destroyed. TTCAR REFERENCES 2. (1) Under TTCAR No.5:10(1) an operator of a Trinidad and Tobago aircraft shall not operate such aircraft in civil aircraft operations unless the Authority has issued an Airworthiness Certificate in respect of that aircraft certifying it to be airworthy. TTCAR No.5:11 prescribes the basic requirements for issue of an Airworthiness Certificate for a Trinidad and Tobago aircraft. Use of the terminology “Airworthiness Certificate” is equivalent to the previously expressed “Certificate of Airworthiness” under previous aviation regulations. Appendix 1 is a sample copy of an Airworthiness Certificate issued under TTCAR No. 5. (2) Under TTCAR No.5:15, an Airworthiness Certificate is valid for one year. This regulation also prescribes the requirements for renewal of an Airworthiness Certificate. (3) TTCAR No.5:12 prescribe the basic requirements for issuing a Special Flight Permit to the operator of a Trinidad and Tobago aircraft where the aircraft is capable of safe flight but unable to meet the applicable airworthiness requirements. -

Gen 1.2 Entry, Transit and Departure of Aircraft

06 DEC 2018 AIP GEN 1.2 - 1 LITHUANIA 06 DEC 2018 GEN 1.2 ENTRY, TRANSIT AND DEPARTURE OF AIRCRAFT 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS 1.1 International flights into, from or over the territory of the Republic of Lithuania are performed under the Rules for the Organisation of the Airspace of the Republic of Lithuania approved by the Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania No. 285 of 17 March 2004 “On Approval of the Regulation for the Organisation of the Airspace of the Republic of Lithuania”. These Rules establish airspace structure and elements thereof, the conditions and procedure for the regulation of the use of the airspace of the Republic of Lithuania, issue and revocation of flight permits. 1.2 Aircraft operating in the controlled airspace may cross the state border area of the Republic of Lithuania on air traffic service routes designated by the air traffic service provider or on other routes pre-coordinated with and authorized by the air traffic service provider. Aircraft operating in the uncontrolled airspace of the border area with the Russian Federation and the Republic of Belarus may cross the state border of the Republic of Lithuania only at its borderline reporting points. Aircraft operating in the uncontrolled airspace of the border area with the Schengen States may cross any point of the state border of the Republic of Lithuania. The Lithuanian Armed Forces shall submit the available information on aircraft, intending to cross the state border or perform flight in the uncontrolled border area airspace of the Republic of Lithuania, to a territorial detachment of the State Border Guard Service under the Ministry of the Interior, in whose operational area the border crossing is to take place. -

61 Part 121—Operating Require

Federal Aviation Administration, DOT Pt. 121 (vi) A signed statement indicating PART 121—OPERATING REQUIRE- that: your company will comply with MENTS: DOMESTIC, FLAG, AND this part and 49 CFR part 40; and you SUPPLEMENTAL OPERATIONS intend to provide safety-sensitive func- tions by contract (including sub- contract at any tier) to a part 119 cer- SPECIAL FEDERAL AVIATION REGULATION NO. 50–2 [NOTE] tificate holder with authority to oper- SPECIAL FEDERAL AVIATION REGULATION NO. ate under part 121 or part 135 of this 71 [NOTE] chapter, an operator as defined in SPECIAL FEDERAL AVIATION REGULATION NO. § 91.147 of this chapter, or an air traffic 97 [NOTE] control facility not operated by the FAA or by or under contract to the Subpart A—General U.S. military. Sec. (2) Send this information to the Fed- 121.1 Applicability. eral Aviation Administration, Office of 121.2 Compliance schedule for operators Aerospace Medicine, Drug Abatement that transition to part 121; certain new Division (AAM–800), 800 Independence entrant operators. Avenue SW., Washington, DC 20591. 121.4 Applicability of rules to unauthorized operators. (3) This Drug and Alcohol Testing 121.7 Definitions. Program Registration will satisfy the 121.9 Fraud and falsification. registration requirements for both 121.11 Rules applicable to operations in a your drug testing program under sub- foreign country. part E of this part and your alcohol 121.15 Carriage of narcotic drugs, mari- testing program under this subpart. huana, and depressant or stimulant drugs (4) Update the registration informa- or substances. tion as changes occur. Send the up- Subpart B—Certification Rules for Domestic dates to the address specified in para- and Flag Air Carriers [Reserved] graph (f)(2) of this section. -

Proposed Rules Federal Register Vol

79891 Proposed Rules Federal Register Vol. 67, No. 251 Tuesday, December 31, 2002 This section of the FEDERAL REGISTER Microsoft Word 97 for Windows or Discussion contains notices to the public of the proposed ASCII text. What events have caused this issuance of rules and regulations. The purpose of these notices is to give interested You may get service information that proposed AD? The FAA has received persons an opportunity to participate in the applies to this proposed AD from reports from Raytheon that during rule making prior to the adoption of the final Raytheon Aircraft Company, 9709 E. manufacturing rivets were not installed rules. Central, Wichita, Kansas 67201–0085; in the following locations: telephone: (800) 429–5372 or (316) 676– • Lower frame forward of the airstair 3140. You may also view this door below the pilot’s floor; • DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION information at the Rules Docket at the Forward of the upper forward address above. corner of the airstair door; Federal Aviation Administration • The bulkhead forward of the cargo FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Mr. door below floor level; and 14 CFR Part 39 Steven E. Potter, Aerospace Engineer, • The lower fuselage panel aft of the [Docket No. 2002–CE–26–AD] Wichita Aircraft Certification Office, wing. FAA, 1801 Airport Road, Wichita, These rivets must be installed for the RIN 2120–AA64 Kansas 67209; telephone: (316) 946– fuselage to carry the ultimate design 4124; facsimile: (316) 946–4407. load. Without the rivets, these areas are Airworthiness Directives; Raytheon understrength. Aircraft Company Model 1900D SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: What are the consequences if the Airplanes Comments Invited condition is not corrected? The AGENCY: Federal Aviation understrength condition in the fuselage Administration, DOT.