Regulating Drone Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customer Guidance for Ferry / Test Flight Handling

Customer Guidance for Ferry / Test flight Handling Customer Service Boeing Shanghai 1 COPYRIGHT © 2010 BOEING SHANGHAI AVIATION SERVICES CO., LTD. Important Notice Important Notice to Customer about Aircraft Input/output PVG procedure Please send the Landing / Departure flight application to CAAC Beijing ATC at least (Five) 5 working days in advance with all necessary information and copy to Boeing Shanghai Customer Service. Please forward the flight permit granted by CAAC ATC to Boeing Shanghai for aircraft customs clearance purpose. All flight crew on board MUST hold “C” or “F” or “M” visa. All technical crew on board MUST hold “F” or “M” visa. Boeing Shanghai can assist Customer in issuing invitation letter upon request. Please fill in the attached Form Comm 001 of Aircraft Information for CIQ declaration purpose and send it to Boeing Shanghai Customer Service at least (Five) 5 working days before the aircraft delivery. Please forward the On – Site Representatives’ passport copies, prior to their arrival, to Boeing Shanghai Customer Service for Entry Permit preparation. COPYRIGHT © 2010 BOEING SHANGHAI AVIATION SERVICES CO., LTD. Important Notice Cont’ Ramp Permit The apron outside of Boeing Shanghai hangar is secured by Shanghai Airport Security Office. Anyone wants to access to aircraft of outside hangar is requested to hold a ramp permit. To get ramp permit, it is necessary for people to have an interview in the Security Office with holding passport , non-criminal statement and company badge. Normally it takes 3 working days to get the permit. For the non- criminal statement, it should be issued by police office or government officials, and notarized by Chinese embassy / consulate; it is also acceptable if it is issued by the foreign embassy / consulate in China. -

Diagnosis & Treatment

1 DIAGNOSIS & TREATMENT DIAGNOSIS STAGE III & STAGE IV COLORECTAL CANCER YOUR GUIDE IN THE FIGHT If you have recently been diagnosed with stage III or IV colorectal cancer (CRC), or have a loved one with the disease, this guide will give you invaluable information about how to interpret the diagnosis, realize your treatment options, and plan your path. You have options, and we will help you navigate the many decisions you will need to make. Your Guide in the Fight is a three-part book designed to empower and point you towards trusted, credible resources. Your Guide in the Fight offers information, tips, and tools to: DISCLAIMER • Navigate your cancer treatment The information and services provided by Fight Colorectal Cancer are for • Gather information for treatment general informational purposes only and are not intended to be substitutes for • Manage symptoms professional medical advice, diagnoses, • Find resources for personal or treatment. If you are ill, or suspect strength, organization and support that you are ill, see a doctor immediately. In an emergency, call 911 or go to • Manage details from diagnosis the nearest emergency room. Fight to survivorship Colorectal Cancer never recommends or endorses any specific physicians, products, or treatments for any condition. FIGHT COLORECTAL CANCER LOOK FOR THE ICONS We FIGHT to cure colorectal cancer and serve as relentless champions of hope Tips and Tricks for all affected by this disease through informed patient support, impactful policy change, and breakthrough Additional Resources -

External Link Teacher Pack

Episode 32 Questions for discussion 13th November 2018 US Midterm Elections 1. Briefly summarise the BTN US Midterm Elections story. 2. What are the midterm elections? 3. How many seats are in the House of Representatives? 4. How many of these seats went up for re-election? 5. What are the names of the major political parties in the US? 6. What words would you use to describe their campaigns? 7. The midterm elections can decide which party has the power in ____________. 8. Before the midterms President Trump had control over both the houses. True or false? 9. About how many people vote in the US President elections? a. 15% b. 55% c. 90% 10. What do you understand more clearly since watching the BTN story? Write a message about the story and post it in the comments section on the story page. WWF Living Planet Report 1. In pairs, discuss the WWF Living Planet Report story and record the main points of the discussion. 2. Why are scientists calling the period since the mid-1900s The Great Acceleration? 3. What is happening to biodiversity? 4. Biodiversity includes… a. Plants b. Animals c. Bacteria d. All of the above 5. What percentage of the planet’s animals have been lost over the last 40 years? 6. What do humans depend on healthy ecosystems for? 7. What organisation released the report? 8. What does the report say we need to do to help the situation? 9. How did this story make you feel? 10. What did you learn watching the BTN story? Check out the WWF Living Planet Report resource on the Teachers page. -

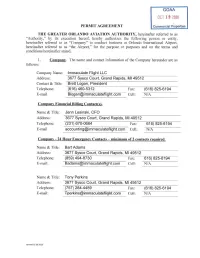

Immaculate Flight Permit Agreement

GOAA OCT 19 2020 PERMIT AGREEMENT Commercial Propert\2s THE GREATER ORLANDO AVIATION AUTHORITY, hereinafter referred to as "Authority," by its execution hereof, hereby authorizes the following person or entity, hereinafter referred to as "Company" to conduct business at Orlando International Airport, hereinafter referred to as "the Airport," for the purpose or purposes and on the terms and conditions hereinafter stated. 1. Company. The name and contact information of the Company hereunder are as follows: Company Name: Immaculate Flight LLC Address: 3677 Sysco Court, Grand Rapids, Ml 49512 Contact & Title: Brett Logan , President Telephone: (616) 460-5312 rax: (616) 825-6194 E-mail [email protected] Cell: N/A Company Financial Billing Contact(s). Name & Title: Jenn Lesinski, CFO Address: 3677 Sysco Court, Grand Rapids, Ml 49512 Telephone: (231) 670-0664 Fax: 616) 825-6194 E-mail [email protected] Cell: N/A 1 Compam - 24 Hour Emergency Contacts - minimum of 2 contacts required. Name & Title: Bart Adams Address: 3677 Sysco Court, Grand Rapids, Ml 49512 Telephone: (859) 494-8730 Fax: 616) 825-6194 E-mai l: [email protected] Cell: N//\ Name & Title: Tony Perkins Address: 3677 Sysco Court, Grand Rapids, Ml 49512 Telephone: (757) 284-4489 Fax: (616) 825-6194 E-mail: [email protected] Cell: NIA rev, sed 02.06 2020 Company Insurance Contact Name & Title: Jenn Lesinski, CFO Address: -- 36f7 Sysco·coui-(-Grand ·Raplcfa,-- MT495f2··-------------- ----- ------ Telephone: (231) 670-0664 Fax: (616) 825-6194 E-mail: [email protected] Cell: NIA Company Authorized Signature Contact Access Control (all badges and key requests') Name & Title: Brandon Brent , Central Florida Regional Sales Manager Address: 3677 Sysco Court, Grand Rapids, Ml 49512 Telephone: (407) 429-8623 Fax: (616) 825-6194 E-mail: [email protected] Cell: NIA 2. -

The Human Planet

INTRODUCTION: THE HUMAN PLANET our and a half billion years ago, out of the dirty halo of cosmic dust left over from the creation of our sun, a spinning clump of minerals F coalesced. Earth was born, the third rock from the sun. Soon after, a big rock crashed into our planet, shaving a huge chunk off, forming the moon and knocking our world on to a tilted axis. The tilt gave us seasons and currents and the moon brought ocean tides. These helped provide the conditions for life, which first emerged some 4 billion years ago. Over the next 3.5 billion years, the planet swung in and out of extreme glaciations. When the last of these ended, there was an explosion of complex multicellular life forms. The rest is history, tattooed into the planet’s skin in three-dimensional fossil portraits of fantastical creatures, such as long-necked dinosaurs and lizard birds, huge insects and alien fish. The emergence of life on Earth fundamentally changed the physics of the planet.1 Plants sped up the slow 1 429HH_tx.indd 1 17/09/2014 08:22 ADVENTURES IN THE ANTHROPOCENE breakdown of rocks with their roots, helping erode channels down which rainfall coursed, creating rivers. Photosynthesis transformed the chemistry of the atmosphere and oceans, imbued the Earth system with chemical energy, and altered the global climate. Animals ate the plants, modifying again the Earth’s chemistry. In return, the physical planet dictated the biology of Earth. Life evolves in response to geological, physical and chemical conditions. In the past 500 million years, there have been five mass extinctions triggered by supervolcanic erup- tions, asteroid impacts and other enormous planetary events that dramatically altered the climate.2 After each of these, the survivors regrouped, proliferated and evolved. -

The Columbian Exchange: a History of Disease, Food, and Ideas

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 24, Number 2—Spring 2010—Pages 163–188 The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian hhee CColumbianolumbian ExchangeExchange refersrefers toto thethe exchangeexchange ofof diseases,diseases, ideas,ideas, foodfood ccrops,rops, aandnd populationspopulations betweenbetween thethe NewNew WorldWorld andand thethe OldOld WWorldorld T ffollowingollowing thethe voyagevoyage ttoo tthehe AAmericasmericas bbyy ChristoChristo ppherher CColumbusolumbus inin 1492.1492. TThehe OldOld WWorld—byorld—by wwhichhich wwee mmeanean nnotot jjustust EEurope,urope, bbutut tthehe eentirentire EEasternastern HHemisphere—gainedemisphere—gained fromfrom tthehe CColumbianolumbian EExchangexchange iinn a nnumberumber ooff wways.ays. DDiscov-iscov- eeriesries ooff nnewew ssuppliesupplies ofof metalsmetals areare perhapsperhaps thethe bestbest kknown.nown. BButut thethe OldOld WWorldorld aalsolso ggainedained newnew staplestaple ccrops,rops, ssuchuch asas potatoes,potatoes, sweetsweet potatoes,potatoes, maize,maize, andand cassava.cassava. LessLess ccalorie-intensivealorie-intensive ffoods,oods, suchsuch asas tomatoes,tomatoes, chilichili peppers,peppers, cacao,cacao, peanuts,peanuts, andand pineap-pineap- pplesles wwereere aalsolso iintroduced,ntroduced, andand areare nownow culinaryculinary centerpiecescenterpieces inin manymany OldOld WorldWorld ccountries,ountries, namelynamely IItaly,taly, GGreece,reece, andand otherother MediterraneanMediterranean countriescountries (tomatoes),(tomatoes), -

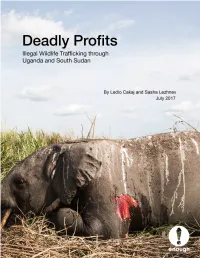

Deadly Profits: Illegal Wildlife Trafficking Through Uganda And

Cover: The carcass of an elephant killed by militarized poachers. Garamba National Park, DRC, April 2016. Photo: African Parks Deadly Profits Illegal Wildlife Trafficking through Uganda and South Sudan By Ledio Cakaj and Sasha Lezhnev July 2017 Executive Summary Countries that act as transit hubs for international wildlife trafficking are a critical, highly profitable part of the illegal wildlife smuggling supply chain, but are frequently overlooked. While considerable attention is paid to stopping illegal poaching at the chain’s origins in national parks and changing end-user demand (e.g., in China), countries that act as midpoints in the supply chain are critical to stopping global wildlife trafficking. They are needed way stations for traffickers who generate considerable profits, thereby driving the market for poaching. This is starting to change, as U.S., European, and some African policymakers increasingly recognize the problem, but more is needed to combat these key trafficking hubs. In East and Central Africa, South Sudan and Uganda act as critical waypoints for elephant tusks, pangolin scales, hippo teeth, and other wildlife, as field research done for this report reveals. Kenya and Tanzania are also key hubs but have received more attention. The wildlife going through Uganda and South Sudan is largely illegally poached at alarming rates from Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, points in West Africa, and to a lesser extent Uganda, as it makes its way mainly to East Asia. Worryingly, the elephant -

Airworthiness Requirements Ac S – Areas of Operation: Task B

AIRWORTHINESS REQUIREMENTS AC S – AREAS OF OPERATION: TASK B How do you prepare for a flight? PAVE: Pilot, Aircraft Environment and External Pressures. PILOT A pilot must continually make decisions about competency, condition of health, mental and emotional state, level of fatigue, and many other variables. AIRCRAFT A pilot frequently bases decisions on evaluation of the airplane, such as performance, equipment, or airworthiness. This task will concentrate on the aircraft (ASEL – Airplane Single Engine Land). ENVIRONMENT The environment encompasses many elements that are not pilot or airplane related, including such factors as weather, air traffic control (ATC), navigational aids, terrain, takeoff and landing areas and surrounding obstacles. Weather is one element that can change drastically over time and distance. EXTERNAL PRESSURES The pilot must evaluate the three previous areas to decide on the desirability of under- taking or continuing the flight as planned. It is worth asking why the flight is being made, how critical it is to maintain the schedule, and if the trip is worth the risks. P – Pilot for the Private Pilot: Start with I’M SAFE: Illness, medication, stress, alcohol (.04), fatigue (acute and chronic) and eating/emotional factors. If any of these factors apply, you should not fly. As a private pilot, you are required to carry your pilot’s certificate, medical and a government ID. As a private pilot, you are allowed to carry passengers (not for hire) – 61.113, fly when visibility is less than 3 miles (SVFR – Special VFR) and can fly without visual reference to the surface. Special requirements for the Private Pilot are: Must be a Private Pilot to take off and land within (KSFO) Class B Airspace (AIM 3-2-3) and can fly at night. -

Airport Rules & Regulations

Restated Airport Rules & Regulations Effective Date: May 4th, 2020 Hollywood Burbank Airport 2627 Hollywood Way Burbank, CA 91505 Table of Contents Chapter 1 – General ..................................................................................................... 6 1.1 General Provisions ........................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Requirement to Comply with Applicable Laws ............................................................................... 6 1.3 AOA Considered to Be Public Property with Controlled/Restricted Access .................................. 6 1.4 Emergency Powers/Authorities ....................................................................................................... 6 1.5 Definitions ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1.6 Boundaries ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 2 – Conduct .................................................................................................. 10 2.1 Damage to or Destruction of Airport Property .............................................................................. 10 2.2 Health ............................................................................................................................................. 10 2.3 Right of Inspection ........................................................................................................................ -

Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade

Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade Trade Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade The Costs of Crime, Insecurity and Institutional Erosion Katherine Lawson and Alex Vines Katherine Lawson and Alex Vines February 2014 Chatham House, 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0)20 7957 5700 E: [email protected] F: +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Charity Registration Number: 208223 Global Impacts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade The Costs of Crime, Insecurity and Institutional Erosion Katherine Lawson and Alex Vines February 2014 © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2014 Chatham House (The Royal Institute of International Affairs) is an independent body which promotes the rigorous study of international questions and does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: + 44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Charity Registration No. 208223 ISBN 978 1 78413 004 6 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Cover image: © US Fish and Wildlife Service. Six tonnes of ivory were crushed by the Obama administration in November 2013. Designed and typeset by Soapbox Communications Limited www.soapbox.co.uk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Latimer Trend and Co Ltd The material selected for the printing of this report is manufactured from 100% genuine de-inked post-consumer waste by an ISO 14001 certified mill and is Process Chlorine Free. -

Airventure NOTAM

NOTAM Special Flight Procedures effective 6 AM CDT July 19 to Noon CDT July 29, 2019 For a free, printed copy of this NOTAM booklet, call EAA at 1-800-564-6322. To view or download this information, visit www.eaa.org/notam, or www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/notices. Table of Contents Preflight Planning ...................................... 1 VFR Route Planning Guide ................... 2-3 Fisk VFR Arrival to OSH ........................ 4-7 Fisk VFR Arrival Runway Paths ........... 8-11 Fond du Lac Diversion Procedure ........... 12 Oshkosh Airport Notes ............................. 13 VFR & IFR Departure from Oshkosh . 14-15 Turbine/Warbird Arrival ............................ 16 AirVenture Seaplane Base ...................... 17 Helicopter Arrival/Departure..................... 18 Ultralight Arrival/Departure ...................... 19 Fond du Lac Arrival/Departure ........... 20-21 Appleton Arrival/Departure ................ 22-23 IFR Arrival/Departure ......................... 24-27 Canadian Pilots ....................................... 28 Oshkosh No-Radio Arrival ....................... 28 Flight Service Information ........................ 29 Changes for 2019 include: New procedure for diversion to Fond du Lac Restriction on transponder use removed IFR routing changes Manitowoc (MTW) VOR decommissioned Numerous text and graphics changes This notice does not supersede restrictions contained in other FDC NOTAMs. Be sure to check current NOTAMs. Flight Procedures Effective July 19-29, 2019 Preflight Planning For one week -

On the Trail of the Perfect Wildlife Film Natural History Cameraman Graham Macfarlane on How the Varicam Lt Meets the Challenges of Shooting in the Wild

PROFESSIONAL CAMERA ON THE TRAIL OF THE PERFECT WILDLIFE FILM NATURAL HISTORY CAMERAMAN GRAHAM MACFARLANE ON HOW THE VARICAM LT MEETS THE CHALLENGES OF SHOOTING IN THE WILD Freelance cameraman Graham Macfarlane has Graham paired the camera with a Canon CN7 lens for the "It's a real headache to focus in 4K these days so I was been lucky enough to travel the world in the majority of the shoot, with the occasional addition of a CN20 spending a lot of time using it, and it was one of the first long lens, when working at more of a distance. things I liked - it's clear and very usable. It's the first pursuit of his passion for wildlife camera for a few years that I've thought about buying cinematography. From chimps to cheetahs, Filming primarily at 800 ISO, he was able to make use of the myself." VariCam LT's dual native 5000 ISO setting a handful of times, he's seen it all and put cameras through their such as at sunset. Graham has also put the VariCam LT through its paces in a paces. Now based in Japan, the Bristolian is forthcoming series following chimpanzees in the one of the BBC Natural History Unit's main Out on the Kenyan plains during the day, however, there was Cameroonian jungle. The choice to go with the VariCam came usually more than enough light. Two separate shoots saw the contributors and has worked on series such as about due to the darkened environment created by the thick crew spending a total of around eight weeks out on location.