Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family

Thesis for Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies Men and Masculinities in the Changing Japanese Family by Hiroko Umegaki Lucy Cavendish College Submitted November 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian & Middle Eastern Studies provided by Apollo View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by 1 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit of the relevant Degree Committee. 2 Acknowledgments Without her ever knowing, my grandmother provided the initial inspiration for my research: this thesis is dedicated to her. Little did I appreciate at the time where this line of enquiry would lead me, and I would not have stayed on this path were it not for my family, my husband, children, parents and extended family: thank you. -

How the World Ought to Work

How the World Ought to Work By D.G. Laderoute “Seppun-san,” Akodo Toturi asked, “why, exactly, are we here?” A restrained patience tightened Seppun Ishikawa’s reply, like he was answering a child. “Once again, Akodo-san, we are going to meet someone.” Toturi narrowed his eyes. He’d been to the Higashikawa District perhaps one other time in his life, but was put off by its freewheeling, garish, commercial character. The racket of street vendors and merchants, hawking what struck him as mostly junk, clamored around them. At least the rabble was good at distracting itself, barely glancing at the two of them, apparently unremarkable rōnin in drab kimonos and broad, conical straw hats. Toturi kept his gaze on Ishikawa. He was tempted to simply command him to stop being so enigmatic, and actually answer the damned question; being the Emerald Champion, he could do that. But he didn’t, because it might upset their fragile…not friendship. Relationship, at best. In the past three weeks, that relationship had settled into an equilibrium, albeit one as delicate as dragonfly wings. The fact was, Toturi needed Ishikawa. The Seppun provided him a window into the politics and bureaucracy of the Imperial court, one he wouldn’t otherwise have, at least as long as he sought to anonymously track his would-be assassins. Three weeks had also given them no leads beyond ruling out a few, admittedly unlikely, perpetrators. Ishikawa slowed as a crowd spilled out of a shabby sake house called Bitter Oblivion. The resulting commotion gave Toturi a chance to lean close to the Seppun and speak. -

A World Like Ours: Gay Men in Japanese Novels and Films

A WORLD LIKE OURS: GAY MEN IN JAPANESE NOVELS AND FILMS, 1989-2007 by Nicholas James Hall A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Nicholas James Hall, 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines representations of gay men in contemporary Japanese novels and films produced from around the beginning of the 1990s so-called gay boom era to the present day. Although these were produced in Japanese and for the Japanese market, and reflect contemporary Japan’s social, cultural and political milieu, I argue that they not only articulate the concerns and desires of gay men and (other queer people) in Japan, but also that they reflect a transnational global gay culture and identity. The study focuses on the work of current Japanese writers and directors while taking into account a broad, historical view of male-male eroticism in Japan from the Edo era to the present. It addresses such issues as whether there can be said to be a Japanese gay identity; the circulation of gay culture across international borders in the modern period; and issues of representation of gay men in mainstream popular culture products. As has been pointed out by various scholars, many mainstream Japanese representations of LGBT people are troubling, whether because they represent “tourism”—they are made for straight audiences whose pleasure comes from being titillated by watching the exotic Others portrayed in them—or because they are made by and for a female audience and have little connection with the lives and experiences of real gay men, or because they circulate outside Japan and are taken as realistic representations by non-Japanese audiences. -

SIÊU BÃO ĐỊA CẦU Geostorm Géotempête

CHƯƠNG TRÌNH GIẢI TRÍ TRÊN CHUYẾN BAY INFLIGHT ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE GUIDE DE DIVERTISSEMENT À BORD 03-04 | 2018 SIÊU BÃO ĐỊA CẦU Geostorm Géotempête Up to 500 hours of entertainment Chào mừng Quý khách trên chuyến bay của Vietnam Airlines! Với hình ảnh bông sen vàng thân quen, LotuStar là thành quả của quá trình không ngừng nâng cao của Vietnam Airlines với mong muốn mang đến cho quý khách những phút giây giải trí thư giãn trên chuyến bay. Chữ “Star” – “Ngôi sao” được Vietnam Airlines lựa chọn đưa vào tên gọi của cuốn chương trình giải trí như một ẩn dụ cho hình ảnh các ngôi sao điện ảnh, ngôi sao ca nhạc sẽ xuất hiện trong các chương trình giải trí. “Ngôi sao”, hơn thế nữa, còn đại diện cho mục tiêu mà Vietnam Airlines đang hướng tới: chất lượng phục vụ quí khách ngày càng hoàn hảo hơn. Mỗi trang thông tin trong cuốn cẩm nang hứa hẹn mang đến cho Quý khách một thế giới nghe-nhìn sôi động với các bộ phim điện ảnh kinh điển, những bộ phim bom tấn, các tác phẩm âm nhạc bất hủ, đang được yêu thích, các chương trình sách nói và chương trình trò chơi lôi cuốn, hấp dẫn. Tất cả các nội dung trên đều được sắp xếp, trình bày theo từng chuyên mục để thuận tiện cho lựa chọn của Quý khách. Và bây giờ, xin mời Quý khách cùng du hành vào thế giới giải trí trên chuyến bay của Vietnam Airlines…. Welcome aboard! LotuStar, your inflight entertainment guide, will give you details of an exciting and diversified entertainment programme, representing Vietnam Airlines’ endeavour to make your flight a relaxing experience. -

No Time and No Place in Japan's Queer Popular Culture

NO TIME AND NO PLACE IN JAPAN’S QUEER POPULAR CULTURE BY JULIAN GABRIEL PAHRE THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in East Asian Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: Professor Robert Tierney ABSTRACT With interest in genres like BL (Boys’ Love) and the presence of LGBT characters in popular series continuing to soar to new heights in Japan and abroad, the question of the presence, or lack thereof, of queer narratives in these texts and their responses has remained potent in studies on contemporary Japanese visual culture. In hopes of addressing this issue, my thesis queries these queer narratives in popular Japanese culture through examining works which, although lying distinctly outside of the genre of BL, nonetheless exhibit queer themes. Through examining a pair of popular series which have received numerous adaptations, One Punch Man and No. 6, I examine the works both in terms of their content, place and response in order to provide a larger portrait or mapping of their queer potentiality. I argue that the out of time and out of place-ness present in these texts, both of which have post-apocalyptic settings, acts as a vehicle for queer narratives in Japanese popular culture. Additionally, I argue that queerness present in fanworks similarly benefits from this out of place and time-ness, both within the work as post-apocalyptic and outside of it as having multiple adaptations or canons. I conclude by offering a cautious tethering towards the future potentiality for queer works in Japanese popular culture by examining recent trends among queer anime and manga towards moving towards an international stage. -

Homosexuality and Manliness in Postwar Japan

Homosexuality and Manliness in Postwar Japan Japan’s first professionally produced, commercially marketed and nationally distributed gay lifestyle magazine, Barazoku (‘The Rose Tribes’), was launched in 1971. Publicly declaring the beauty and normality of homosexual desire, Barazoku electrified the male homosexual world whilst scandalizing mainstream society, and sparked a vibrant period of activity that saw the establishment of an enduring Japanese media form, the homo magazine. Using a detailed account of the formative years of the homo magazine genre in the 1970s as the basis for a wider history of men, this book examines the rela- tionship between male homosexuality and conceptions of manliness in postwar Japan. The book charts the development of notions of masculinity and homo- sexual identity across the postwar period, analysing key issues including public/ private homosexualities, inter-racial desire, male–male sex, love and friendship; the masculine body; and manly identity. The book investigates the phenomenon of ‘manly homosexuality’, little treated in both masculinity and gay studies on Japan, arguing that desires and individual narratives were constructed within (and not necessarily outside of) the dominant narratives of the nation, manliness and Japanese culture. Overall, this book offers a wide-ranging appraisal of homosexuality and manliness in postwar Japan, that provokes insights into conceptions of Japanese masculinity in general. Jonathan D. Mackintosh is Lecturer in Japanese Studies at Birkbeck, University of London, -

The Influence of Politics and Culture on English Language Education in Japan

The Influence of Politics and Culture on English Language Education in Japan During World War II and the Occupation by Mayumi Ohara Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Certificate of Original Authorship I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Production Note: Signature removed prior to publication. Mayumi Ohara 18 June, 2015 i Acknowledgement I owe my longest-standing debt of gratitude to my husband, Koichi Ohara, for his patience and support, and to my families both in Japan and the United States for their constant support and encouragement. Dr. John Buchanan, my principal supervisor, was indeed helpful with valuable suggestions and feedback, along with Dr. Nina Burridge, my alternate supervisor. I am thankful. Appreciation also goes to Charles Wells for his truly generous aid with my English. He tried to find time for me despite his busy schedule with his own work. I am thankful to his wife, Aya, too, for her kind understanding. Grateful acknowledgement is also made to the following people: all research participants, the gatekeepers, and my friends who cooperated with me in searching for potential research participants. I would like to dedicate this thesis to the memory of a research participant and my friend, Chizuko. -

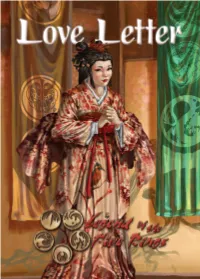

LL-L5R Rules.Pdf

A few months ago, the Empress of Rokugan’s third child, Iweko Miaka, came of age. This instantly made her the most eligible maiden in the Empire, and prominent samurai from every clan and faction have set out to court her. Of course, in Rokugan marriage is a matter of duty and politics far more often than love, but the personal affection of a potential spouse can be a very effective tool in marriage negotiations. And when that potential spouse is an Imperial princess, her affection can be more influential than any number of political favors. 2 Of course, winning a princess’ heart is hardly an easy task in the tightly- monitored world of the Imperial Palace. The preferred tool of courtly romance in Rokugan is the letter, and every palace’s corridors are filled with the soft steps of servants carrying letters back and forth. But such letters can be intercepted by rivals or turned away by hostile guards. For a samurai to succeed in his suit, he will have to find ways of getting his own letters into Miaka’s hands – while blocking the similar efforts of rival suitors. 3 Object In the wake of many recent tragic events, Empress Iweko I has sought to bring a note of joy back to the Imperial City, Toshi Ranbo, by announcing the gempukku (coming- of-age) of her youngest child and only daughter, Iweko Miaka. Prominent samurai throughout the Imperial City have immediately started to court the Imperial princess, whose hand in marriage would be a prize beyond price in Rokugan. -

The Politics of Difference and Authenticity in the Practice of Okinawan Dance and Music in Osaka, Japan

The Politics of Difference and Authenticity in the Practice of Okinawan Dance and Music in Osaka, Japan by Sumi Cho A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jennifer E. Robertson, Chair Professor Kelly Askew Professor Gillian Feeley-Harnik Professor Markus Nornes © Sumi Cho All rights reserved 2014 For My Family ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my advisor and dissertation chair, Professor Jennifer Robertson for her guidance, patience, and feedback throughout my long years as a PhD student. Her firm but caring guidance led me through hard times, and made this project see its completion. Her knowledge, professionalism, devotion, and insights have always been inspirations for me, which I hope I can emulate in my own work and teaching in the future. I also would like to thank Professors Gillian Feeley-Harnik and Kelly Askew for their academic and personal support for many years; they understood my challenges in creating a balance between family and work, and shared many insights from their firsthand experiences. I also thank Gillian for her constant and detailed writing advice through several semesters in her ethnolab workshop. I also am grateful to Professor Abé Markus Nornes for insightful comments and warm encouragement during my writing process. I appreciate teaching from professors Bruce Mannheim, the late Fernando Coronil, Damani Partridge, Gayle Rubin, Miriam Ticktin, Tom Trautmann, and Russell Bernard during my coursework period, which helped my research project to take shape in various ways. -

Boys Love Comics As a Representation of Homosexuality in Japan

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Japanskt mál og menning Boys love Comics as a Representation of Homosexuality in Japan Ritgerð til BA-prófs í japönsku máli og menningu Brynhildur Mörk Herbertsdóttir Kt.: 190994-2019 Leiðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir Maí 2018 1 Abstract This thesis will focus on a genre of manga and anime called boys love, and compare it to the history of homosexuality in Japan and the homosexual culture in modern Japanese society. The boys love genre itself will be closely examined to find out which tropes are prevalent and why, as well as what its main demographic is. The thesis will then describe the long history of homosexuality in Japan and the similarities that are found between the traditions of the past and the tropes used in today’s boys love. Lastly, the modern homosexual culture in Japan will be examined, to again compare and contrast it to boys love. 2 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Boys love: History, tropes, and common controversies ....................................................................... 6 Stylistic appearance and Seme Uke in boys love ............................................................................ 8 Boys love Readers‘ Demography .................................................................................................... 9 History of male homosexual relationships in Japan and the modern boys love genre ...................... 12 -

Gay Glossary Laws Against Homosexual Activity, and Has Some Legal Protections for Gay Individuals

lgbt Overview The concept of homosexuality in Japan isn’t a new concept. Much like the Ancient Greeks, same sex (specifically male-male) relationships in ancient Japan were considered a higher form of love. In modern times, Japan has no gay glossary laws against homosexual activity, and has some legal protections for gay individuals. In addition, there are some legal protections for transgender ゲイ individuals. (gei ) gay In the kind of environment where being gay is not considered 100% 'real,' it is natural that many LGBT people do get married. Like most of Asia, Japan is a ホモ, ホモセクシュアル highly conformist society, and refusing to marry is a mark of egregious (homo or homosekushuaru) nonconformity and may even prevent you from advancing in your career. homosexual Being openly gay in Japan only rubs the fact of this nonconformity in, making for an environment where gay & lesbian Japanese people rarely venture out レズ, レズビアン of the closet - at least before night falls. (rezu or rezubian) lesbian But the good news is that you are a foreigner! Foreigners are already “weird” and “different,” so you’re not necessarily expected to be normal according to 同性愛者 Japanese social norms. It has also been said that being gay is a foreign (dōseiaisha) problem (akin to how much of the crime in Japan is blamed on foreigners) but lit. same-sex-loving person don’t worry, the perceptions of the LGBT community are changing for the better. More and more, gay characters are on variety shows, written into ニューハーフ plots, in popular culture, and even in political office. -

Burakumin and Shimazaki Toson's Hakai: Images of Discrimination in Modern Japanese Literature

Burakumin and Shimazaki Toson's Hakai: Images of Discrimination in Modern Japanese Literature Andersson, René 2000 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Andersson, R. (2000). Burakumin and Shimazaki Toson's Hakai: Images of Discrimination in Modern Japanese Literature. Institutionen för Östasiatiska Språk,. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Burakumin and Shimazaki Tôson’s Hakai: Images of Discrimination in Modern Japanese Literature René Andersson 1 Published by: Dept. of East Asian Languages Lund University P.O. Box 713, SE – 220 07 Lund SWEDEN Tel: +46–46–222–9361 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 91-628-4538-1 TO MY FATHER AAGE 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENT ..................................................................................