The Last of the Peshwas : a Tale of the Third Maratha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

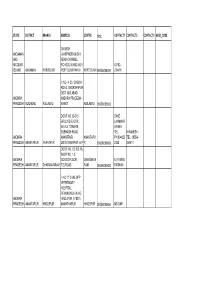

Industry Indcd Industry Type Commissio Ning Year Category

Investme Water_Co Industry_ Commissio nt(In nsumptio Industry IndCd Type ning_Year Category Region Plot No. Taluka Village Address District Lacs) n(In CMD) APAR Industries Ltd. Dharamsi (Special nh Desai Oil SRO Marg Refinary Mumbai Mahul Mumbai 1 Div.) 9000 01.Dez.69 Red III Trombay city 1899 406 Pirojshah nagar E.E. Godrej SRO Highway Industries Mumbai Vikhroli Mumbai 2 Ltd. 114000 06.Nov.63 Red III (E) city 0 1350 Deonar SRO Abattoir Mumbai S.No. 97 Mumbai 3 (MCGM) 214000 Red III Govandi city 450 1474.5 Love Groove W.W.T.F Municipal Complex Corporati ,Dr Annie on of Beasant BrihannM SRO Road Mumbai 4 umbai 277000 04.Jän.38 Red Mumbai I Worli city 100 3000 Associate d Films Industries SRO 68,Tardeo Mumbai 5 Pvt. Ltd. 278000 Red Mumbai I Road city 680 100 CTS No. 2/53,354, Indian 355&2/11 Hume 6 Antop Pipe SRO Hill, Mumbai 6 Comp. Ltd 292000 01.Jän.11 Red Mumbai I Wadala(E) city 19000 212 Phase- III,Wadala Truck Terminal, Ultratech Near I- Cement SRO Max Mumbai 7 Ltd 302000 01.Jän.07 Orange Mumbai I Theaters city 310 100 R68 Railway Locomoti ve Western workshop Railway,N s / .M. Joshi Carriage Integrate Marg Repair d Road SRO N.M. Joshi Lower Mumbai 8 Workshop 324000 transport 26.Dez.23 Red Mumbai I Mumbai Marg Parel city 3750 838 A G Khan Worly SRO Road, Mumbai 9 Dairy 353000 04.Jän.60 Red Mumbai I Worly city 8.71 2700 Gala No.103, 1st Floor, Ashirward Est. -

Mahindra Everyday

ISSUE 1, 2013 ISSUE 1, 2013 WHAT’S INSIDE? Mahindra e2o Launched: Set to Redefine the Future of Mobility World Class Tractor Plant Inaugurated in Andhra Pradesh MSSSPL’s Golden Journey Of 50 Years 8th Annual Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards Announced Special Feature: The Mahindra Institute of Quality Mahindra Everyday 1 ISSUE 1, 2013 CONTENTS CULTURAL COVER STORY 04 OUTREACH 35 Mahindra USA’s exciting and eventful On the art and culture front, initiatives story of growth and success, from showcased old world culture, the world’s 1994 to date. best guitar and music talent, excellence in theatre and more. INTERNATIONAL AWARDS FOR OPERATIONS 11 EXCELLENCE 40 The Mahindra Group’s international A spectrum of awards, including the action stretched from Serbia to Sri first Mahindra Sustainability awards Lanka, South Africa and elsewhere recognising diverse sustainability around the globe. initiatives, was recently presented. SECTOR BRIEFS 13 SUSTAINABILITY 47 As ever there was plenty happening Efforts and initiatives towards across sectors and in all spheres of preserving, safeguarding and sustaining action – new plants, new products, our planet and its precious resources. distinguished visitors, certifications and celebrations. Please write in to [email protected] to give feedback on this issue. ME TEAM Associate Editors: Zarina Hodiwalla, Darius Lam Soumi Rao Chandrika Rodrigues Col. Abhijit Dasgupta AS, Kandivli MLDL Mahindra Management Dev. Center Asha Sabharwal Stella Rozario AS, Nashik MTWL Santosh Tandav Mahindra Partners Shirish Kulkarni Pradeep Zoting AS, Igatpuri FES, Nagpur Vrinda Pisharody Tech Mahindra & K.P. Narsimha Rao Pavitra Kamdadai Mahindra Satyam AS, Zaheerabad MNEPL Rajeev Malik Venecia Paulose Martin Cisneros Preeti Nair MVML, Chakan Mahindra USA Mahindra Navistar Edited and Published by Roma Balwani Nitin Panday Swapnil Soudagar Pooja Thawrani for Mahindra & Mahindra Limited, Gateway Mahindra Swaraj Systech Mahindra Reva Building, Apollo Bunder, Mumbai 400 001. -

Agricultural Plot / Land for Sale in Jawan Tungi Road Area, Lonavala

https://www.propertywala.com/P48221806 Home » Lonavala Properties » Commercial properties for sale in Lonavala » Agricultural Plots / Lands for sale in Jawan Tungi Road area, Lonavala » Property P48221806 Agricultural Plot / Land for sale in Jawan Tungi Road area, Lonavala 36 lakhs Hilton Resort Touch Beautiful Mountain And Advertiser Details Valley Touch Plot For Sale At Pavana Dam Near Lonavala. Pavana Dam Near Pavana Nagar , Pavananagar - Paud R… Area: 20000 SqFeet ▾ Facing: North West Transaction: Resale Property Price: 3,600,000 Rate: 180 per SqFeet -15% Possession: Immediate/Ready to move Scan QR code to get the contact info on your mobile Description View all properties by Shraddha Estates Lonavala Plot details and Description:-¿¿ Pictures Plot Area :- 20 Guntha ( 22000 sq/ft) Price :- 36 Lacs. Plot Details:-¿¿ 1) !! Single owner !! plot. Aerial View Side View 2) !! Tar Road Touch !!Plot. 3) All Papers are !! clear and clean !! from year 1960. 4)Precasted !! Compound wall !! of plot. 5) Front side of the plot beautiful !! pavana lake water view.!! 6)Behind side of plot Beautiful scientific !! Mountain and valley.!! !! Milky waterfowls and Sunset View.!! 7) !! Survey and Demarcation !! is Done. Aerial View Side View 8)Plot is Good For built up small !! farmhouse or Bunglow !! for !! weekends for holidays !! second home option is also good. 9)!! Investment option !! is also good for Future Life. 10) Plot is Located at !! Shilimb Village !! at proper Pavana dam. 11) Front of The !! Famous Resort Hilton !!. DISTANCE FROM PLOT :- ¿¿ -

Current Ecological Status and Identification of Potential Ecologically Sensitive Areas in the Northern Western Ghats

CURRENT ECOLOGICAL STATUS AND IDENTIFICATION OF POTENTIAL ECOLOGICALLY SENSITIVE AREAS IN THE NORTHERN WESTERN GHATS OCTOBER 2010 INSTITUTE OF ENVIRONMENT EDUCATION AND RESEARCH BHARTI VIDYAPEETH DEEMED UNIVERSITY PUNE, MAHARASHTRA TABLE OF CONTENTS Team at BVIEER...............................................................................................iv Acknowledgements.............................................................................................v Disclaimer .........................................................................................................vi Terms of reference ............................................................................................vii Framework ......................................................................................................viii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................1 HISTORY OF CONSERVATION IN THE WESTERN GHATS.........................2 CURRENT THREATS TO THE WESTERN GHATS...........................................................................................2 CONCEPT OF ECOLOGICALLY SENSITIVE AREAS (ESAS).......................3 NEED FOR IDENTIFYING ESAs IN THE WESTERN GHATS......................3 DEFINING ESAs ..............................................................................................4 GENESIS OF ESAs IN INDIA ..........................................................................5 CHAPTER 2: ECOLOGICAL STATUS OF THE NORTHERN WESTERN GHATS..............................................................................................7 -

15 Appendix.Pdf

^ N c b , <3TS!T^ i|R ^l<^l ^ R?H|c|^ 919M ^Fn^TT^KTHT^ :?^19 ^^KsId'cbKlT^) qr4t ^ 6 6 H^KI'^ ^<=hK^I PtSl^MNd €rU«ll^<=b ^C% f^Ff^T ^Kcil-M ^1^^ s»5)^m*^l, ^ Rf^RFllRl f^«=bR. «TR-dl<^c1 3^lO^‘J|R R^T ^oq MWO-dleH (XmI^'^i) ^ ?ol9 f»5l^ 5T=hK ^i^Tf^ ^1^1 °MI<9MI ^qo W«FT, P^o6UAj|^r mR c| [^ch|u|. - <3T '3TSJT^ q q^f^TcT^ f^dl^ f^TcTFjft 51M^q 5TSFr?T ■#. ?o«, i^q^^Terr, Mob 9860698730 E.mail- [email protected] Tt^ ^ 3TTt. ^ 5^ (Rl^MN^cft) ^«imsFT ^ '3Tit. Tnir ^ept t ^Ki^^icfi^ ? | ^ ^ ,3^ q^RFs^rte FlWt ff^ 5FbR, TR«IT, ^ « n , FTSFT, FTftFT, ^^1=15, cFfT, f- t^FPft ElPH^ <3T^=qFT '371%. aiiq^l f^FPft HlF^cfl MM^M ^ci<+)<ld ^TcRR ^ 3 ^ ciMl^ft %t fcFMt. FlfMt % l f ^ %cpqT^ q f^pcfT qfx:p^ q ^ wfteFf ^EFlfFl^hr FqMtrl '3 1 ^ . 3 T R ^ H T # qi F^ltsFT f^^41c1F EI$<75|4 =h<cfl^. ^ 061%, f^Tmt FH- ^ ;- 8. FT. ^ ^Tf^ ^R d l 5FFT- FT. FFFKTFT^ 5R^. f ^ m R^KMI '3T^=qRT" 5fW arTT^ Hlf^cTt srt^^PTTcT ?IT^. 3HNiJ||cb4H ^^^TTft TTTfMr ^■'ibo6i|| ^5TFTT ^T?I. ^ K ) 3 7 f^ Hlf^cfl ^^IcO'MI '+>HKM^N< ^ f^P#t. Bio- Data <1. 'ilcj : qcm : 5. 'Ji-nai'd^ : «. 2PT 4. ^ / 5 ^ 3HIM^ H<xll, pfrTT^ : (9. oqc|<ri|iJ '^•Ml'^sfl': c. i - ^ / ^ <^. -

Impact of Physical and Sociox

Impact of physical and socio-economical factors on agricultural scenario of Nashik District (MS) 1991 – 2011 A thesis submitted to, Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) In Department of earth Science (Geography) Under the board of Faculty of Moral and Social Science studies Submitted By Pandurang Dnyanadev Yadav Under The Guidance of Dr. Nanasaheb R. Kapadnis February 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “IMPACT OF PHYSICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMICAL FACTORS ON AGRICULTURAL SCENARIO OF NASHIK DISTRICT (M.S.) 1991 to 2011.” completed and written by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. (PANDURANG DNYANADEV YADAV) ResearchStudent Place: Pune Date: February,2016. I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “IMPACT OF PHYSICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMICAL FACTORS ON AGRICULTURAL SCENARIO OF NASHIK DISTRICT (M.S.) 1991 to 2011.”Which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in Earth Science (Geography) of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Pandurang Dnyanadev Yadav under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body upon him. (DR. NANASAHEB R. KAPADNIS) Research Guide Place: Pune Date: February, 2016. II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I express my deep sense of gratitude and sincere feelings to Dr. -

A Profile of the Study Area

CHAPTER TWO A PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA Grapes came to India from the Eastern Mediterranean region through Iran and Afghanistan in the century. But their real development began from 1930 when the first vineyard was developed in the Nashik district of Maharashtra (Bhujabal, 1988, p. 2). Basically grapes are grown in the warm temperate regions but because of the favourable conditions prevailing in certain parts of a tropical country like India, grapes are also grown successfully in our country. Besides, the new agricuhural techniques and the introduction of new and more adaptable seedless varieties have helped in the expansion of areas under viticulture in India. Within the framework of physical environmental conditions required for growing of grapes, certain changes have been made in the technique of growing of grapes in such tropical regions. Hence it is necessary to study the physical environmental conditions in the context of two aspects: first, the physical environmental conditions for growing of grapes in general and second, the general profile of the region under study namely the Nashik district. As the chief objective of this research project is to present a geographical analysis of grape cultivation in Nashik district, it is first necessary to outline the general profile of the study area. For this purpose the present chapter is divided into two units: the physical setting and the cultural setting of the district. 2.1 PHYSICAL SETTING OF THE DISTRICT The physical setting of the district is studied here with respect to 1. Location 2. Geology and Topography 3. Drainage 4. Climate 5. Soil 2.1.1 LOCATION Nashik district lies in the northern part of Maharashtra State. -

Internet of Things Technology, Sensor Devices and Big Data”

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN MULTIDISCIPLINARY FIELD (ISSN: 2455-0620) (Scientific Journal Impact Factor: 6.719) Monthly Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Research Journal Index Copernicus International Journal Master list with - IC Value: 86.87 One Day International e-Seminar on “Internet of things Technology, Sensor Devices and Big Data” ( 19th December, 2020 ) Seminar Special Issue - 20 DEC - 2020 (Seminar Special Issue) RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY & PUBLICATION Email: [email protected] Web Email: [email protected] WWW.IJIRMF.COM One Day International e-Seminar on Internet of things Technology, Sensor Devices and Big Data (IoTSDBD– 2020) 19th December, 2020 Special Issue – 20 The Managing Editor: Dr. Chirag M. Patel (Research Culture Society & Publication) Jointly Organized By Department of Computer Science & Department of Physics, Sir Sayyed College of Arts, Commerce & Science Aurangabad (MS) India. and Research Culture Society IoTSDBD– 2020 Page 1 International e-Seminar on Internet of Things Technology, Sensor Devices and Big Data (IoTSDBD– 2020) 19th December, 2020 Special Issue – 20 Copyright: © Department of Computer Science & Department of Physics, Sir Sayyed College Of Arts, Commerce & Science, Aurangabad (MS) India and Research Culture Society editors and authors of this Conference issue. Disclaimer: The author/authors are solely responsible for the content of the papers compiled in this seminar/conference proceedings special issue. The publisher or editors does not take any responsibility for the same in any manner. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. -

Chapter I Introduction

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study Wine is an ancient potation particularly for the classic Old World wine regions of the world. The Old World wines belong to the legendary winemaking regions of France, Italy, Spain, Germany and Austria. The vintners from this region perceive wine as a mark of cultural heritage and emphasize on the importance of "terroir" in making the Old World wines unique. In contrast the New World wine regions of United States, Australia, Chile, Argentina and South Africa highlight the versatility of the wine grape varietals and the expertise of the winemaker in producing such fine wines. Truong (2012) noted that the countries belonging to the New World wine region took competitive advantage of the off - cycle growing seasons in the southern hemisphere to boost the export market of their wines. Additionally, the New World nations like United States and Australia benefitted from ample land while Chile. Argentina and South Africa benefitted from cheap labour that gave further fillip to winemaking in these countries. The study of Truong (2012) further stated that the appearance of the two new super powers - China and India and their developing taste for wine has been instrumental in reshaping the global wine industry. Still in an emerging stage, the domestic wine industry is primarily oriented towards the domestic market and less towards exports. It is chiefly driven by positive consumer trends induced by rise in discretionary spending potential (Jacob, 2008; Berry, 2010). Traditionally, wine does not figure prominently in the Indian potation and the consumption trend is heavily weighted towards liquors like whisky and rum. -

Abstract Reg LD-2009

NATIONAL REGISTER OF LARGE DAMS – 2009 FOREWORD PREFACE ABSTRACT DAMS OF NATIONAL IMPORTANCE ( COMPLETED AND ONGOING) STATE-WISE DISTRIBUTION OF LARGE DAMS:- Height 10 to 15 metres. Height more than 15 metres. Height more than 15 metres or storage more than 60 m cubic metre Height more than 50 metres. State-wise distribution of large dams (existing & ongoing) in India - Column graph Decade-wise distribution of large dams - Column graph State-wise distribution of completed large dams in India – Pie diagram State-wise distribution of ongoing large dams in India – Pie diagram STATE-WISE DETAILS OF LARGE DAMS : - Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andhra Pradesh Arunachal Pradesh Assam Bihar Chhattisgarh Goa Gujarat Himachal Pradesh Jammu & Kashmir Jharkhand Karnataka Kerala Maharashtra Madhya Pradesh Manipur Meghalaya Orissa Punjab Rajasthan Sikkim Tamil Nadu Tripura Uttrakhand Uttar Pradesh West Bengal FOREWORD With the ever increasing population and the consequent increasing demand for water for various uses, it has become necessary not only to construct new dams but also rehabilitate and maintain existing ones. The dams provide storages to tide over the temporal and spatial variation in rainfall for meeting the year round requirements of drinking water supply, irrigation, hydropower and industries in the country which lead to development of the national economy. Dams have helped immensely in attaining self sufficiency in foodgrain production besides flood control and drought mitigation. The maintenance of these dams in good health is a serious matter, as failure of any dam would result in huge loss of life and property. Thus safety of dams and allied structures is an important issue that needs to be continuously monitored for ensuring public confidence, protection of downstream areas from potential hazard and ensuring continued accrual of benefits from the large national investments. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE CHURCH ANDAMAN LANEPHOENIX BAY AND NEAR CARAMEL NICOBAR SCHOOL WARD NO 6 03192- ISLAND ANDAMAN PORTBLAIR PORT BLAIR744101 PORT BLAIR BKID0008091 234400 H NO 4 -35 CINEMA ROAD BHOKTHAPUR DIST ADILABAD ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH - PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD 504001 ADILABAD BKID0005652 DOOR NO.12-313, SAKE GROUND FLOOR, LAXMINAR BALAJI TOWERS, AYANA, SUBHASH ROAD, TEL. K.RAMESH, ANDHRA ANANTPUR, ANANTAPU PH:994825 TEL. 08554- PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTPUR DIST:ANANTPUR, A.P R BKID0008689 2352 249411 DOOR NO. 12-100-1A, SHOP NO. 1-3, ANDHRA GOUND FLOOR, DHARMAVA K.THIMMA PRADESH ANANTAPUR DHARMAVARAM R.S.ROAD RAM BKID0005629 RATNAM H NO 17 3 645 OPP VETERINARY HOSPITAL PENUKONDA ROAD ANDHRA HINDUPUR 515201, PRADESH ANANTAPUR HINDUPUR ANANTHAPUR HINDUPUR BKID0005654 MD SAFI BANK OF INDIA, C. RAMAPURAM BRANCH, 4-1, GROUND FLOOR, C. RAMAPURAM VILLAGE, TIRUPATHI RURAL, CHITTOOR DIST., ANDHRA BR MGR ANDHRA PRADESH, PIN: 0877- PRADESH CHITTOOR C. RAMAPURAM 517561 CHITTOOR BKID0005718 2247096 IST FL.,MUNICIPAL SHOPPING COMPLEX, PRAKASAM HIGH SHRI N. G. ROAD, P.B.NO.13, REDDY, SHRI S. DIST. CHITTOOR, SR. SUBRAMANIA, ANDHRA MANAGER, SR. MANAGER, ANDHRA PRADESH.PIN 517 TEL:08572- TEL:08572- PRADESH CHITTOOR CHITOOR 001. CHITTOOR BKID0008670 233327 233327 D.NO-2-41,MAIN ROAD, KAYAMPETA- VILL,BRAHMANAPAT TU-PO, VADAMALPETA- ANDHRA MANDAL, CHITTOOR- VADAMALP 08577- 919959762 PRADESH CHITTOOR KAYAMPETA DIST, PIN-517551 ET BKID0005645 237929 RAMESH KVS 526 XVI 601 AND 608,SRI SAI,HARSHA COMPLEX,KAMMAPA LLI,EAST NIMMAPALI X ROAD, MADANAPALLI- ANDHRA 517325,CHITTOR MADANAPA 789332257 PRADESH CHITTOOR MADANAPALLI ANDHRA PRADESH LLE BKID0005646 0 7893322570 B-50/1, AIR BYPASS ROAD, OPP. -

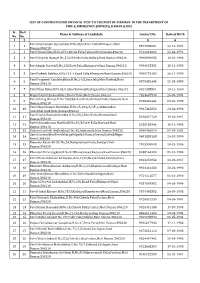

3. List of Candidates with Roll Number of Fireman

LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR PHYSICAL TEST TO THE POST OF FIREMAN IN THE DEPARTMENT OF FIRE & EMERGENCY SERVICES, DAMAN & DIU. Sr. Roll Name & Address of Candidate Contact No. Date of Birth No. No. 1 2 3 5 6 Patel Indravadan Sureshbhai,H.No.35/2,Patel Falia,Bhimpore,Nani 1 1 9574990001 22-10-1991 Daman.396210 2 2 Patel Vilash Natu,H.No.374,Chheda Falia,Patlara,Moti Daman.396220 9712016664 22-04-1991 3 3 Patel Divyesh Nattu,H.No.374,Chheda Falia,Patlara,Moti Daman.396220 9998899835 10-02-1994 4 4 Patel Anish Naresh,H.No.256,Patel Falia,Bhimpore,Nani Daman.396210 9904223335 13-11-1989 5 5 Patel Rakesh Kalidas,H.No.142-4,Kund Falia,Bhimpore,Nani Daman.396210 9909773454 26-11-1989 Patel Pragnesh Ranchhodbhai,H.No.24/3,Sura falia,Moti Vankad,Nani 6 6 9879481444 21-03-1989 Daman.396210 7 7 Patel Vijay Babu,H.No.93/1,Nani Koliwad,Kachigam,Nani Daman.396210 9924385501 13-12-1990 8 8 Halpati Ankit Bachu,H.No.2,Boria Talav,Moti Daman.396220 7383687998 26-05-1996 Patel Chirag Umesh,H.No.193/3,School Falia,Prakash Falia,Dalwada,Nani 9 9 9726332442 05-02-1995 Daman.396210 Patel Mayurkumar Kantibhai,H.No.15-183/A/4F-2,Abhinandan 10 10 9925345853 23-06-1996 Appt.Khariwad,Nani Daman.396210 Patel Harsh Rameshchandra,H.No.59/2,Patel Falia,Marwad,Nani 11 11 8156017729 19-02-1997 Daman.396210 Patel Shivamkumar Kantilal,H.No.59/5,Patel Falia,Marwad,Nani 12 12 8238185946 19-12-1993 Daman.396210 13 13 Halpati Kamlesh Budhabhai,H.No.42,Ambawadi,Moti Daman.396220 8980406519 01-04-1993 Ganvit Sumanbhai Devubhai,patelpada,kilvani,silvassa,Dadra&Nagar 14 14 9601830168