OLDWAYS AFRICANA SOUP in STORIES Edited by Stephanie Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Beanery

344 appendix Basic Beanery name(s) origin & CharaCteristiCs soaking & Cooking Adzuki Himalayan native, now grown Soaked, Conventional Stovetop: 40 (aduki, azuki, red Cowpea, throughout Asia. Especially loved in minutes. unSoaked, Conventional Stovetop: red oriental) Japan. Small, nearly round red bean 1¼ hours. Soaked, pressure Cooker: 5–7 with a thread of white along part of minutes. unSoaked, pressure Cooker: the seam. Slightly sweet, starchy. 15–20 minutes. Lower in oligosaccharides. Anasazi New World native (present-day Soak? Yes. Conventional Stovetop: 2–2¹⁄² (Cave bean and new mexiCo junction of Arizona, New Mexico, hours. pressure Cooker: 15–18 minutes appaloosa—though it Colorado, Utah). White speckled with at full pressure; let pressure release isn’t one) burgundy to rust-brown. Slightly gradually. Slow-Cooker: 1¹⁄² hours on sweet, a little mealy. Lower in high, then 6 hours on low. oligosaccharides. Appaloosa New World native. Slightly elongated, Soak? Yes. Conventional Stovetop: 2–2¹⁄² (dapple gray, curved, one end white, the other end hours. pressure Cooker: 15–18 minutes; gray nightfall) mottled with black and brown. Holds let pressure release gradually. Slow- its shape well; slightly herbaceous- Cooker: 1¹⁄² hours on high, then 6–7 piney in flavor, a little mealy. Lower in hours on low. oligosaccharides. Black-eyed pea West African native, now grown and Soak? Optional. Soaked, Conventional (blaCk-eyes, lobia, loved worldwide. An ivory-white Stovetop: 20–30 minutes. unSoaked, Chawali) cowpea with a black “eye” across Conventional Stovetop: 45–55 minutes. the indentation. Distinctive ashy, Soaked, pressure Cooker: 5–7 minutes. mineral-y taste, starchy texture. unSoaked, pressure Cooker: 9–11 minutes. -

Great Chefs® of the Caribbean©

GREAT CHEFS® OF THE © CARIBBEAN Episode Appetizer Entrée Dessert Number Episode 1 Honduran Scallop Ceviche Veal Roulade with Sage Sauce Pithiviers On DVD Douglas Rodriguez Stéphane Bois Pierre Castagne Aquarela Le Patio Le Perroquet “Carib” #1 El San Juan Hotel Village St. Jean St. Maarten Puerto Rico St.-Barthélemy Episode 2 Curried Nuggets of Lobster Swordfish with Soy-Ginger Banana Napoleon with On DVD Norma Shirley Beurre Blanc Chocolate Sabayon Norma at the Wharfside Scott Williams Patrick Lassaque “Carib” #1 Montego Bay, Jamaica Necker Island Resort The Ritz-Carlton Cancun Necker Island, BVI Mexico Episode 3 Seared Yellowfin Tuna and Caribbean Stuffed Lobster Pineapple Surprise On DVD Tuna Tartare on Greens Ottmar Weber Rolston Hector “Carib” #1 Wilted in Sage Cream Ottmar’s at The Grand Pavilion The St. James’s Club Michael Madsen Hotel Antigua Great House Grand Cayman Villa Madeleine St. Croix Episode 4 Black Bean Cake and Lamb Chop with Mofongo and Turtle Bay’s Chocolate On DVD Butterflied Shrimp with Chili Cilantro Pesto Banana Tart Beurre Blanc Jeremie Cruz Andrew Comey “Carib” #2 Janice Barber El Conquistador Resort Caneel Bay Resort The White House Inn Puerto Rico St. John USVI St. Kitts Episode 5 Foie Gras au Poireaux with Swordfish Piccata Chocolate-layered Lime On DVD Truffle Vinaigrette David Kendrick Parfait with Raspberry Coulis Pierre Castagne Kendrick’s Josef Teuschler “Carib” #2 Le Perroquet St. Croix Four Seasons Resort St. Martaan Nevis Episode 6 Garlic-crusted Crayfish Tails Baked Fillet of Sea Bass with Chocolate -

Christopher & Melissa

CANAL HOUSE COOKING VOLUME N°3 has just arrived. It is a collection of our favorite winter and spring recipes, ones we cook for ourselves, our friends, and our families all during the cold win- ter months and straight through the exciting arrival of spring. It’s filled with recipes that will make you want to run into the kitchen and start cooking. We are home cooks writing about home cooking for other home cooks. Our recipes are easy to prepare and completely doable for the novice and experienced cook alike. We make jars of marma- lade for teatime and to gift to our friends. We warm and nourish ourselves with hearty soups and big pots of stews and braises. We roll out pasta and make cannelloni for weekend or special occasion gatherings. We roast root vegetables in the winter and lamb in the spring. Take a peek at some of the pages to the right and see what we are up to. Canal House Cooking Volume N°3, Winter & Spring is the third book of our award-winning series of seasonal recipe collections. We publish three volumes a year: Summer, Fall & Holiday, and Winter & Spring, each filled with delicious recipes for you from us. Cook all winter and through the spring with Canal House Cooking! Christopher & Melissa Copyright © 2010 Christopher Hirsheimer & Melissa Hamilton Photographs copyright © 2010 by Christopher Hirsheimer Canal House Illustrations copyright © 2010 by Melissa Hamilton C o o k i n g All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. -

Redalyc.APPRECIATING CALLALOO SOUP: St. Martin As an Expression

Revista Brasileira do Caribe ISSN: 1518-6784 [email protected] Universidade Federal do Maranhão Brasil Guadeloupe, Francio; Wolthuis, Erwin APPRECIATING CALLALOO SOUP: St. Martin as an expression of the compositeness of Life beyond the guiding fictions of racism, sexism, and class discrimination Revista Brasileira do Caribe, vol. 17, núm. 32, enero-junio, 2016, pp. 227-247 Universidade Federal do Maranhão Sao Luís, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=159148014010 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative APPRECIATING CALLALOO SOUP: St. Martin as an expression of the compositeness of Life beyond the guiding fi ctions of racism, sexism, and class discrimination Francio Guadeloupe President of the University of St. Martin, St. Marteen, St. Martin Erwin Wolthuis Head of the Hospitality and Business Divisions, University of St. Martin St. Marteen, St. Martin RESUMO A sopa Callaloo é, simultaneamente, uma comida caribenha e, nacional “outra”. Diferente a sua preparação em outros povos e lugares, Callaloo pode ser compreendida como um convite para apreciar os diferentes mundos interconectados de nossa coletiva experiência do colonialismo ocidental e da resistência que este provocou. Isto pode ser entendido como uma composição natural do mundo e da dinâmica de vida que a triada da discriminação racista, sexista e de classe ocultou e ainda reforça essa situação. Adotando a sopa Callaloo como uma metáfora guia, os autores focalizam novas vias para esmiuçar práticas do ser e outras opressões do povo de Saint Martin. -

Cooking Club Lesson Plan Spanish Grades 6-12 I. Lesson Objectives

Cooking Club Lesson Plan Spanish Grades 6-12 I. Lesson Objectives: A. Students will discuss Latin American culture, cuisine, and cooking practices. B. Students will state the key messages from MyPlate and identify its health benefits. C. Students will prepare and sample a healthy, easy-to-make Latin American dish. II. Behavior Outcomes: A. Follow MyPlate recommendations: make half your plate fruits and vegetables, aiming for variety in color, at least half your grains whole, and switch to fat-free or low-fat milk and milk products. III. Pennsylvania Educational Standards: A. 11.3 Food Science and Nutrition B. 1.6 Speaking and Listening C. 10.1 Concepts of Health D. 10.2 Healthful Living E. 10.4 Physical Activity IV. Materials A. Handouts-“MyPlate” handout in English and Spanish, copies of recipe B. Visual: MyPlate graphic poster from Learning Zone Express or other appropriate visual aid C. Additional Activities- “MiPlato- Get to know the food groups” D. Any other necessary materials E. Optional: reinforcement that conveys the appropriate nutrition message F. Hand wipes, gloves, hairnets/head coverings, aprons, tablecloth G. Food and cooking supplies needed for recipe H. Paper products needed for preparing and serving recipe (i.e. plates, bowls, forks, spoons, serving utensils, etc.) I. Ten Tips Sheet: ”Liven Up Your Meals With Fruits and Vegetables” or other appropriate tips sheet V. Procedure: Text in italics are instructions for the presenter, non-italicized text is the suggested script. Drexel University, CC-S Spanish Lesson Plan, revised 6/19, Page 1 A. Introductory 1. Lesson Introduction a. Introduce yourself and the nutrition education program/organization presenting the lesson. -

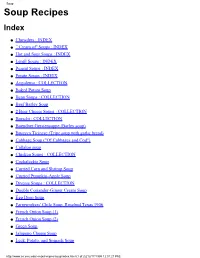

Soup Recipes Index

Soup Soup Recipes Index ● Chowders : INDEX ● ``Cream of'' Soups : INDEX ● Hot and Sour Soups : INDEX ● Lentil Soups : INDEX ● Peanut Soups : INDEX ● Potato Soups : INDEX ● Avgolemo : COLLECTION ● Baked Potato Soup ● Bean Soups : COLLECTION ● Beef Barley Soup ● 2 Beer Cheese Soups : COLLECTION ● Borscht : COLLECTION ● Buendner Gerstensuppe (Barley soup) ● Busecca Ticinese (Tripe soup with garlic bread) ● Cabbage Soup ("Of Cabbages and Cod") ● Callaloo soup ● Chicken Soups : COLLECTION ● Cockaleekie Soup ● Curried Corn and Shrimp Soup ● Curried Pumpkin-Apple Soup ● Diverse Soups : COLLECTION ● Double Coriander-Ginger Cream Soup ● Egg Drop Soup ● Farmworkers' Chile Soup, Rosebud Texas 1906 ● French Onion Soup (1) ● French Onion Soup (2) ● Green Soup ● Jalapeno Cheese Soup ● Leek, Potato, and Spinach Soup http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~mjw/recipes/soup/index.html (1 of 2) [12/17/1999 12:01:27 PM] Soup ● Lemongrass Soup ● Miso Soup (1) ● Mom's Vegetable Soup ● Mullagatawny Soup (1) ● Mullagatawny Soup (2) ● Noodle Soup(Ash-e Reshteh) ● Pepper Soups : COLLECTION ● Posole : COLLECTION ● Pumpkin Soup ● Pumpkin Soup - COLLECTION ● Quebec Pea Soup / Salted herbs ● Quick & Dirty Miso Soup ● Reuben Soup ● Smoked Red Bell Pepper Soup ● Soups With Cheese : COLLECTION ● Split Pea Soup ● Squash and Orange Soup ● Sweet & Sour Cabbage Soup ● Posole : COLLECTION ● Tomato Soups / Gazpacho : COLLECTION ● Tortellini Soups : COLLECTION ● Two Soups (Stephanie da Silva) ● Vegetable Soup ● Vegetarian Posole ● Vermont Cheddar Cheese Soup ● Watercress Soup amyl http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~mjw/recipes/soup/index.html -

Stock Vs. Broth: Are You Confused? Kim Schuette, CN Certified GAPS Practitioner

Stock vs. Broth: Are You Confused? Kim Schuette, CN Certified GAPS Practitioner French chefs have a term fonds de cuisine, which translates “the foundation and working capital of the kitchen.” Bone and meat stock provide just that, the foundation of both the kitchen and ultimately one’s physical health. One of the most common Questions that those individuals embarking upon the GAPS Diet™ have is “Do I make stock or broth?” What is the difference between the two? The two words are often used interchangeably by the most educated of chefs. For the purpose of the GAPS Diet™, Dr. Natasha Campbell-McBride uses the terms “meat stock” and “bone stock.” In this paper, I will use “meat stock” when referencing meat stock and “bone broth” for bone stock. Meat stock, rather than bone broth, is used in the beginning stages of the GAPS Diet™, especially during the Introduction Diet where the primary focus is healing the gut. Bone broth is ideal for consuming once gut healing has taken place. The significant difference is that the meat stock is not cooked as long as bone broth. Meat stock is especially rich in gelatin and free amino acids, like proline and glycine. These amino acids, along with the gelatinous protein from the meat and connective tissue, are particularly beneficial in healing and strengthening connective tissue such as that found in the lining of the gut, respiratory tract, and blood/brain barrier. These nutrients are pulled out of the meat and connective tissue during the first several hours of cooking meaty fish, poultry, beef and lamb. -

APRIL 2021 Menu

APRIL 2021 Menu MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY 1 2 Cinnamon Toast Blueberry Muffins AM Snack Milk Water Shepherds Pie Cheese Pizza Green Beans Seasoned Corn Lunch Diced Pears Juicy Sliced Peaches Milk Milk Vegetarian Meal: Veggie Pie Nacho Chips/Soft Tortilla & Cheese Dip PM Snack Spring Party & Egg Hunt Water 5 6 7 8 9 Biscuits & Gravy Waffles Apple Cinnamon Oatmeal Bagel & Cream Cheese Whole Grain Cereal AM Snack Water Water Water Water Milk Chicken & Rice Casserole Salisbury Steak & Gravy Egg and Cheese McMuffins Spaghetti Vegetarian Lasgna Seasoned Corn Mashed Potatoes Tator Tots Green Beans Lima Beans Lunch Diced Pears Juicy Pineapple Tidbits Juicy Sliced Peaches Applesauce Tropical Fruit Milk Milk Milk Milk Milk Vegetarian Meal: Cheesy Rice Vegetarian Meal: Veggie Patty Warm Cinnamon Rolls Orange Slices & Graham Crackers Cheerios & Raisins Applesauce & Vanilla Wafers Pizza Bagels PM Snack 100% Fruit Juice Water Water Water 100% Fruit Juice 12 13 14 15 16 French Toast Sticks Cheesy Tator Tots English Muffin W/ Grape Jelly Bananas & Yogurt Egg & Cheese Croissants AM Snack Water Water Water Water Water Chicken & Potato Bowl Juicy Cheese Burgers Mile High Taco Bean Pie Cheese Tortellini Mac & Cheese Seasoned Corn French Fries Lima Beans Green Beans Green Peas Lunch Sweet Pineapple Tidbits Juicy Sliced Peaches Tropical Fruit Diced Pears Sweet Pineapple Tidbits Milk Milk Milk Milk Milk Vegetarian Meal: Cheesy Potato Bowl Vegetarian Meal: Veggie Burger Sliced Cheese & Crackers Mozzarella Sticks W/ Marinara Trail Mix Sliced Apples -

Download Ivar's Chowders Nutritional Information

A Northwest Soup Tradition Widely recognized as one of the finest food purveyors in the country, Ivar’s Soup & Sauce Company produces top-quality seafood soups, and sauces at our state-of-the-art facility in Mukilteo, Washington. Our soup tradition began in 1938 when Ivar Haglund began making and selling his homemade clam chowder on the Seattle waterfront. Today, along with our original line of Ivar’s seafood soups and chowders, we produce a selection of original, non-seafood recipes and new classics. Ivar’s also develops custom soups for restaurants and food-service companies, and they’re all made with the same tradition of quality that has made us famous since 1938. Ivar’s Soup & Sauce Company • 11777 Cyrus Way, Mukilteo, WA 98275 • Ivars.com Alder Smoked Salmon Chowder RTH For more information please contact our sales department at 425 493 1402 Savor the irresistible flavor of wild Alaskan smoked salmon, blended with tender potatoes and vegetables in this rich and creamy chowder. Preparation time: 30 minutes Main Ingredients: Potatoes, smoked salmon, garlic, Distribution Item Number: onion, celery, spices, Parmesan and Romano cheese Manufacturers’ Code: 969 Shelf Life: Three months refrigerated or 18 months Contents: Four 4-pound pouches of soup, ready to use. frozen. Ivar’s Puget Sound Style Clam Chowder Available in concentrated and heat-and-serve versions, this distinctive Northwest-style chowder with a tantalizing hint of bacon is made with meaty clams harvested in the icy waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Preparation Time: 35 minutes Main Ingredients: Sea clams, potatoes, bacon, Distribution Item Number: onions, celery Loaded Baked Potato Soup RTH Manufacturers’ Code: concentrate 9571, heat-and-serve 952 Shelf Life: Three months refrigerated or 18 months frozen. -

Greens, Beans & Groundnuts African American Foodways

Greens, Beans & Groundnuts African American Foodways City of Bowie Museums Belair Mansion 12207 Tulip Grove Drive Bowie MD 20715 301-809-3089Email: [email protected]/museum Greens, Beans & Groundnuts -African American Foodways Belair Mansion City of Bowie Museums Background: From 1619 until 1807 (when the U.S. Constitution banned the further IMPORTATION of slaves), many Africans arrived on the shores of a new and strange country – the American colonies. They did not come to the colonies by their own choice. They were slaves, captured in their native land (Africa) and brought across the ocean to a very different place than what they knew at home. Often, slaves worked as cooks in the homes of their owners. The food they had prepared and eaten in Africa was different from food eaten by most colonists. But, many of the things that Africans were used to eating at home quickly became a part of what American colonists ate in their homes. Many of those foods are what we call “soul food,” and foods are still part of our diverse American culture today. Food From Africa: Most of the slaves who came to Maryland and Virginia came from the West Coast of Africa. Ghana, Gambia, Nigeria, Togo, Mali, Sierra Leone, Benin, Senegal, Guinea, the Ivory Coast are the countries of West Africa. Foods consumed in the Western part of Africa were (and still are) very starchy, like rice and yams. Rice grew well on the western coast of Africa because of frequent rain. Rice actually grows in water. Other important foods were cassava (a root vegetable similar to a potato), plantains (which look like bananas but are not as sweet) and a wide assortment of beans. -

Excerpt from Encyclopedia of Jewish Food

Excerpt from Encyclopedia of Jewish Food Borscht Borscht is a soup made with beets. It may be hot or cold and it may contain meat or be vegetarian. Origin: Ukraine Other names: Polish: barszcz; Russian: borshch; Ukranian: borshch; Yiddish: borsht. Northern Poland and the Baltic States are rather far north, lying in a region with long dark winters, a relatively short growing season, and a limited number of (as well as sometimes an aversion to) available vegetables. During the early medieval period, eastern Europeans began making a chunky soup from a wild whitish root related to carrots, called brsh in Old Slavonic and cow parsnip in English. Possibly originating in Lithuania, the soup spread throughout the Slavic regions of Europe to become, along with shchi (cabbage soup), the predominant dish, each area giving the name its local slightly different pronunciation. In May, peasants would pick the tender leaves of the brsh to cook as greens, then gather and store the roots to last as a staple through the fall and winter. Typically, a huge pot of brsh stew was prepared, using whatever meat and bones one could afford and variously adding other root vegetables, beans, cabbage, mushrooms, or whatever was on hand. This fed the family for a week or more and was sporadically refreshed with more of the ingredients or what was found. The root’s somewhat acrid flavor hardly made the most flavorsome of soups, even with the addition of meat, but the wild roots were free to foragers; brsh was one of the few vegetables available to peasants during the winter and provided a flavor variation essential to the Slavic culture. -

Cold Starters

Cold starters Chicken liver pate 19 a jar of delicate chicken liver pate served with crunchy baguette Cold meat selection 21 smoked lard, duck and roast beef Taka już jest natura ludzkości Że dąży ku doskonałości Ale nic jej się tak nie udało W tym dążeniu jak wódka i sało! Kabaret „Czwarta Rano” Tartar Horde (three types for two persons) 82 selection of original meat tartar beef, deer and venision with selection of additives (one type for one person) 42 Ulica warszawska przed laty doradzała: „Małą wódkę, duże piwko, pod tatarka i pieczywko!” Gelfilte fisz 29 Jewish-style carp Smoked fish selection 29 by Chef's grandmother's recipe Do każdego rachunku od 6 osób doliczamy serwis w wysokości 10% 1 Stuffed eggs 21 with crayfish meat and olive oil roe Cranberry foie gras 39 orbs of duck liver in cranberry with hazelnut and quince chips Dressed herring 32 galician herring salad with potatoes, carrots, beetroots, onion and mayonaisse I wreszcie on, srebrzystej wódki, Koniecznie dużej, zimnej, czystej, Najulubieńszy druh srebrzysty. Julian Tuwim o śledziu Polish cheese selection 44 four different types of polish cheese served with marmolade and hazelnuts Baltic herring 26 served with marinated onion in honey-mustard sauce Venision aspic 26 aspic with wild boar neck served with beetroot mousse, garlic sauce and buckwheat groats chips 2 Caviar served with buckwheat groats baguette and butter Sturgeon caviar 189 Antonius Caviar 5* Pike roe 34 Soups "St. Jack's" chicken broth 29 intensive chicken broth served with homemade noodles, quail egg and beef-chicken meatballs Borscht with dumplings 24 rich beetroot soup with vegetables, parsley, sour cream and duck dumplings (vege option: no sour cream, mushroom dumplings) Crayfish soup a la Franz Fischer 33 bisque from crayfish shells with julienne vegetables and whole crayfish Jeśli Bóg humor ceni, to w niebie Franciszek Co dzień zupę ma dobrą i pełny kieliszek.