The Integumentary System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nail Anatomy and Physiology for the Clinician 1

Nail Anatomy and Physiology for the Clinician 1 The nails have several important uses, which are as they are produced and remain stored during easily appreciable when the nails are absent or growth. they lose their function. The most evident use of It is therefore important to know how the fi ngernails is to be an ornament of the hand, but healthy nail appears and how it is formed, in we must not underestimate other important func- order to detect signs of pathology and understand tions, such as the protective value of the nail plate their pathogenesis. against trauma to the underlying distal phalanx, its counterpressure effect to the pulp important for walking and for tactile sensation, the scratch- 1.1 Nail Anatomy ing function, and the importance of fi ngernails and Physiology for manipulation of small objects. The nails can also provide information about What we call “nail” is the nail plate, the fi nal part the person’s work, habits, and health status, as of the activity of 4 epithelia that proliferate and several well-known nail features are a clue to sys- differentiate in a specifi c manner, in order to form temic diseases. Abnormal nails due to biting or and protect a healthy nail plate [1 ]. The “nail onychotillomania give clues to the person’s emo- unit” (Fig. 1.1 ) is composed by: tional/psychiatric status. Nail samples are uti- • Nail matrix: responsible for nail plate production lized for forensic and toxicology analysis, as • Nail folds: responsible for protection of the several substances are deposited in the nail plate nail matrix Proximal nail fold Nail plate Fig. -

Sweat Glands • Oil Glands • Mammary Glands

Chapter 4 The Integumentary System Lecture Presentation by Steven Bassett Southeast Community College © 2015 Pearson Education, Inc. Introduction • The integumentary system is composed of: • Skin • Hair • Nails • Sweat glands • Oil glands • Mammary glands © 2015 Pearson Education, Inc. Introduction • The skin is the most visible organ of the body • Clinicians can tell a lot about the overall health of the body by examining the skin • Skin helps protect from the environment • Skin helps to regulate body temperature © 2015 Pearson Education, Inc. Integumentary Structure and Function • Cutaneous Membrane • Epidermis • Dermis • Accessory Structures • Hair follicles • Exocrine glands • Nails © 2015 Pearson Education, Inc. Figure 4.1 Functional Organization of the Integumentary System Integumentary System FUNCTIONS • Physical protection from • Synthesis and storage • Coordination of immune • Sensory information • Excretion environmental hazards of lipid reserves response to pathogens • Synthesis of vitamin D3 • Thermoregulation and cancers in skin Cutaneous Membrane Accessory Structures Epidermis Dermis Hair Follicles Exocrine Glands Nails • Protects dermis from Papillary Layer Reticular Layer • Produce hairs that • Assist in • Protect and trauma, chemicals protect skull thermoregulation support tips • Nourishes and • Restricts spread of • Controls skin permeability, • Produce hairs that • Excrete wastes of fingers and supports pathogens prevents water loss provide delicate • Lubricate toes epidermis penetrating epidermis • Prevents entry of -

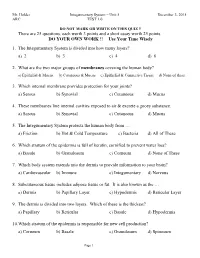

There Are 25 Questions, Each Worth 3 Points and a Short Essay Worth 25 Points. DO YOUR OWN WORK !! Use Your Time Wisely 1. T

Mr. Holder Integumentary System – Unit 5 December 3, 2015 ARC TEST 1.0 DO NOT MARK OR WRITE ON THIS QUIZ !! There are 25 questions, each worth 3 points and a short essay worth 25 points. DO YOUR OWN WORK !! Use Your Time Wisely 1. The Integumentary System is divided into how many layers? a) 2 b) 3 c) 4 d) 6 2. What are the two major groups of membranes covering the human body? a) Epithelial & Mucus b) Cutaneous & Mucus c) Epithelial & Connective Tissue d) None of these 3. Which internal membrane provides protection for your joints? a) Serous b) Synovial c) Cutaneous d) Mucus 4. These membranes line internal cavities exposed to air & excrete a gooey substance. a) Serous b) Synovial c) Cutaneous d) Mucus 5. The Integumentary System protects the human body from … a) Friction b) Hot & Cold Temperature c) Bacteria d) All of These 6. Which stratum of the epidermis is full of keratin, cornified to prevent water loss? a) Basale b) Granulosum c) Corneum d) None of These 7. Which body system extends into the dermis to provide information to your brain? a) Cardiovascular b) Immune c) Integumentary d) Nervous 8. Subcutaneous tissue includes adipose tissue or fat. It is also known as the … a) Dermis b) Papillary Layer c) Hypodermis d) Reticular Layer 9. The dermis is divided into two layers. Which of these is the thickest? a) Papillary b) Reticular c) Basale d) Hypodermis 10. Which stratum of the epidermis is responsible for new cell production? a) Corneum b) Basale c) Granulosum d) Spinosum Page 1 Mr. -

Basic Biology of the Skin 3

© Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHAPTER Basic Biology of the Skin 3 The skin is often underestimated for its impor- Layers of the skin: tance in health and disease. As a consequence, it’s frequently understudied by chiropractic students 1. Epidermis—the outer most layer of the skin (and perhaps, under-taught by chiropractic that is divided into the following fi ve layers school faculty). It is not our intention to present a from top to bottom. These layers can be mi- comprehensive review of anatomy and physiol- croscopically identifi ed: ogy of the skin, but rather a review of the basic Stratum corneum—also known as the biology of the skin as a prerequisite to the study horny cell layer, consisting mainly of kera- of pathophysiology of skin disease and the study tinocytes (fl at squamous cells) containing of diagnosis and treatment of skin disorders and a protein known as keratin. The thick layer diseases. The following material is presented in prevents water loss and prevents the entry an easy-to-read point format, which, though brief of bacteria. The thickness can vary region- in content, is suffi cient to provide a refresher ally. For example, the stratum corneum of course to mid-level or upper-level chiropractic the hands and feet are thick as they are students and chiropractors. more prone to injury. This layer is continu- Please refer to Figure 3-1, a cross-sectional ously shed but is replaced by new cells from drawing of the skin. This represents a typical the stratum basale (basal cell layer). -

Anatomy and Physiology of the Nail

Anatomy and physiology of the nail Christian Dumontier Institut de la Main & hôpital saint Antoine, Paris Anatomy of the nail • The osteo-ligamentous support • Nail plate • All surrounding tissues, i.e. the perionychium The distal phalanx • Is reinforced laterally by the the Flint’s ligament • Which protect the neuro-vascular structures Flint’s ligament The ligamentous support • The nail is fixed onto the bone through a highly vascularized dermis • The nail is fixed onto the bone through two strong ligaments The ligamentous structures • All the ligaments merge together with • The extensor tendon • The flexor tendon • The collateral ligaments • Flint’s ligament • Guero’s dorsal ligament • (Hyponychial ligament) Clinical implications • A normal nail cannot grow on an abnormal support +++ • Large phalanx = racket nails • bony malunion = nail dystrophy • arthrosis = Pincer nail,... The nail plate • Is produced by the germinal matrix • ItsKeratinic shape depends structure, on the bonypartiall supporty transparent and the and integritycurved both of the longitudinall soft-tissuesy arandound transv it ersally • Three different layers • 0,5 mm thickness, 20% of water Clinical applications • The nail plate is often intact in crushing trauma due to its flexibility • And must be removed in order to explore all the lesions +++ The perionychium • Include all the soft- tissues located under the nail plate • Nail (germinal) matrix, • Nail bed, • Hyponychium The perionychium • Soft-tissues aroud the plate (paronychium) proximal and lateral nail wall (fold) -

The Nail Bed, Part I. the Normal Nail Bed Matrix, Stem Cells, Distal Motion and Anatomy

Central Journal of Dermatology and Clinical Research Review Article *Corresponding author Nardo Zaias, Department of Dermatology Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, FL. 33140, 4308 The Nail Bed, Part I. The Normal Alton rd. Suite 750, USA, Email: [email protected] Submitted: 25 November 2013 Nail Bed Matrix, Stem Cells, Distal Accepted: 28 December 2013 Published: 31 December 2013 Copyright Motion and Anatomy © 2014 Zaias Nardo Zaias* OPEN ACCESS Department of Dermatology Mount Sinai Medical Center, USA Abstract The nail bed (NB) has its own matrix that originates from distinctive stem cells. The nail bed matrix stem cells (NBMSC) lie immediately distal to the nail plate (NP) matrix cells and are covered by the keratogenous zone of the most distal NPM (LUNULA). The undivided NBMS cells move distally along the NB basement membrane toward the hyponychium; differentiating and keratinizing at various locations, acting as transit amplifying cells and forming a thin layer of NB corneocytes that contact the overlying onychocytes of the NP, homologous to the inner hair root sheath. At the contact point, the NB corneocytes express CarcinoEmbryonic Antigen (CEA), a glycoprotein-modulating adherence which is also found in hair follicles and tumors. Only when both the NP and the NB are normal do they synchronously move distally. The normal NB keratinizes, expressing keratin K-5 and K-17 without keratohyaline granules. However, during trauma or disease states, it reverts to keratinization with orthokeratosis and expresses K-10, as seen in developmental times. Psoriasis is the only exception. Nail Bed epidermis can express hyperplasia and giant cells in some diseases. -

•Nail Structure •Nail Growth •Nail Diseases, Disorders, and Conditions

•Nail Structure Nail Theory •Nail Growth •Nail Diseases, Disorders, and Conditions Onychology The study of nails. Nail Structure 1. Free Edge – Extends past the skin. 2. Nail Body – Visible nail area. 3. Nail Wall – Skin on both sides of nail. 4. Lunula – Whitened half-moon 5. Eponychium – Lies at the base of the nail, live skin. 6. Mantle – Holds root and matrix. Nail Structure 7. Nail Matrix – Generates cells that make the nail. 8. Nail Root – Attached to matrix 9. Cuticle – Overlapping skin around the nail 10. Nail Bed – Skin that nail sits on 11. Nail Grooves – Tracks that nail slides on 12. Perionychium – Skin around nail 13. Hyponychium – Underneath the free edge Hyponychium Nail Body Nail Groove Nail Bed Lunula Eponychium Matrix Nail Root Free Edge Nail Bed Eponychium Matrix Nail Root Nail Growth • Keratin – Glue-like protein that hardens to make the nail. • Rate of Growth – 4 to 6 month to grow new nail – Approx. 1/8” per month • Faster in summer • Toenails grow faster Injuries • Result: shape distortions or discoloration – Nail lost due to trauma. – Nail lost through disease. Types of Nail Implements Nippers Nail Clippers Cuticle Pusher Emery Board or orangewood stick Nail Diseases, Disorders and Conditions • Onychosis – Any nail disease • Etiology – Cause of nail disease, disorder or condition. • Hand and Nail Examination – Check for problems • Six signs of infection – Pain, swelling, redness, local fever, throbbing and pus Symptoms • Coldness – Lack of circulation • Heat – Infection • Dry Texture – Lack of moisture • Redness -

Science of the Nail Apparatus David A.R

1 CHAPTER 1 Science of the Nail Apparatus David A.R. de Berker 1 and Robert Baran 2 1 Bristol Dermatology Centre , Bristol Royal Infi rmary , Bristol , UK 2 Nail Disease Center, Cannes; Gustave Roussy Cancer Institute , Villejuif , France Gross anatomy and terminology, 1 Venous drainage, 19 Physical properties of nails, 35 Embryology, 3 Effects of altered vascular supply, 19 Strength, 35 Morphogenesis, 3 Nail fold vessels, 19 Permeability, 35 Tissue differentiation, 4 Glomus bodies, 20 Radiation penetration, 37 Factors in embryogenesis, 4 Nerve supply, 21 Imaging of the nail apparatus, 37 Regional anatomy, 5 Comparative anatomy and function, 21 Radiology, 37 Histological preparation, 5 The nail and other appendages, 22 Ultrasound, 37 Nail matrix and lunula, 7 Phylogenetic comparisons, 23 Profi lometry, 38 Nail bed and hyponychium, 9 Physiology, 25 Dermoscopy (epiluminescence), 38 Nail folds, 11 Nail production, 25 Photography, 38 Nail plate, 15 Normal nail morphology, 27 Light, 40 Vascular supply, 18 Nail growth, 28 Other techniques, 41 Arterial supply, 18 Nail plate biochemical analysis, 31 Gross anatomy and terminology with the ventral aspect of the proximal nail fold. The intermediate matrix (germinative matrix) is the epithe- Knowledge of nail unit anatomy and terms is important for lial structure starting at the point where the dorsal clinical and scientific work [1]. The nail is an opalescent win- matrix folds back on itself to underlie the proximal nail. dow through to the vascular nail bed. It is held in place by The ventral matrix is synonymous with the nail bed the nail folds, origin at the matrix and attachment to the nail and starts at the border of the lunula, where the inter- bed. -

Anatomy of Skin Kyle EB

Anatomy of Skin Kyle EB 1.What is wrong with Kyle? 2.How does this condition affect Kyle’s health/life? 3.What is the new treatment? 4.What would you do if you were Kyle? (receive the treatment or not?) The Story of Kyle Hicks http://www.kansas. com/news/local/education/article21264273.html Skin ● The external surface of the body. ● Also referred to as the cutaneous membrane. ● About 16% of an adult’s total body weight. (So if you weigh 100 lbs that means your skin weighs 16 lbs) Structure of the Skin ● Two main parts: ○ Epidermis ■ superficial ■ thinner ■ epithelial tissue ○ Dermis ■ deeper ■ thicker ■ connective tissue *The two layers are attached by the basement membrane. ● Subcutaneous layer (subQ) ○ Also called the hypodermis. ○ Deep to the dermis, but not part of the skin. ○ consists of areolar and adipose ct ○ Attaches skin to underlying tissues and organs. Epidermis ● It is keratinized stratified squamous epithelium ● 4 key cells: 1. Keratinocytes ○ They make the protein keratin (a tough, protective protein). ○ The most numerous cell type: about 90% of the epidermal cells. 2. Melanocytes ○ About 8% of the epidermal cells. ○ Make the protein pigment melanin. ■ contributes to skin color ■ absorbs damaging ultraviolet light. 3. Langerhans cells ○ Immune cells located in the epidermis. 4. Merkel cells ○ associated with touch Layers of the Epidermis ● Most areas of the body have four strata or layers. This is referred to as thin skin. ● In areas of the body exposed to greater friction, like the fingertips, palms and soles of the feet the epidermis has five strata or layers. -

Structure and Function of the Skin

2 Structure and Function of the Skin Skin disease illustrates structure and function. Loss of or Chapter Contents defects in skin structure impair skin function. Skin dis ease is discussed in more detail in the other chapters. ● Epidermis ● Structure ● Other Cellular Components EPIDERMIS ● Dermal–Epidermal Junction – The Basement Membrane Zone ● Dermis ● Skin Appendages Key Points ● Subcutaneous Fat 1. Keratinocytes are the principal cell of the epidermis 2. Layers in ascending order: basal cell, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, stratum corneum 3. Basal cells are undifferentiated, proliferating cells Key Points 4. Stratum spinosum contains keratinocytes connected by desmosomes 1. The major function of the skin is as a barrier to maintain 5. Keratohyalin granules are seen in the stratum granulosum internal homeostasis 6. Stratum corneum is the major physical barrier 2. The epidermis is the major barrier of the skin 7. The number and size of melanosomes, not melanocytes, determine skin color 8. Langerhans cells are derived from bone marrow and are the skin’s first line of immunologic defense ABSTRACT 9. The basement membrane zone is the substrate for attach- ment of the epidermis to the dermis The skin is a large organ, weighing an average of 4 kg and 10. The four major ultrastructural regions of the basement covering an area of 2 m2. Its major function is to act as membrane zone include the hemidesmosomal plaque of a barrier against an inhospitable environment – to pro the basal keratinocyte, lamina lucida, lamina densa, and tect the body from the influences of the outside world. anchoring fibrils located in the sublamina densa region of The importance of the skin is well illustrated by the high the papillary dermis mortality rate associated with extensive loss of skin from burns. -

Nail Abnormalities: Clues to Systemic Disease ROBERT S

COVER ARTICLE CARING FOR COMMON SKIN CONDITIONS Nail Abnormalities: Clues to Systemic Disease ROBERT S. FAWCETT, M.D., M.S., Thomas M. Hart Family Practice Residency Program, York Hospital, York, Pennsylvania SEAN LINFORD, M.D., and DANIEL L. STULBERG, M.D., Utah Valley Family Practice Residency Program, Provo, Utah The visual appearance of the fingernails and toenails may suggest an underlying systemic disease. Clubbing of the nails often suggests pulmonary disease or inflammatory bowel disease. Koilonychia, or “spoon-shaped” nails, may stimulate a work-up for hemochromatosis or anemia. In the absence of trauma or psoriasis, onycholysis should prompt a search for symptoms of hyperthyroidism. The find- ing of Beau’s lines may indicate previous severe illness, trauma, or exposure to cold temperatures in patients with Raynaud’s disease. In patients with Muehrcke’s lines, albumin levels should be checked, and a work-up done if the level is low. Splinter hemorrhage in patients with heart murmur and unex- plained fever can herald endocarditis. Patients with telangiectasia, koilonychia, or pitting of the nails may have connective tissue disorders. (Am Fam Physician 2004;69:1417-24. Copyright© 2004 American Academy of Family Physicians.) areful examination of in ridging or splitting. A transient prob- the fingernails and toe- lem causing growth disturbance may lead nails can provide clues to the formation of transverse lines across to underlying systemic the nail plate, as in Mees’, Muehrcke’s, diseases (Table 1). Club- and Beau’s lines (Figure 2). Changes in Cbing, which is one example of a nail the configuration of the capillaries in manifestation of systemic disease, was the proximal nail bed are responsible first described by Hippocrates in the fifth for some of the alterations that occur in century B.C.1 Since that time, many more patients with connective tissue disorders, nail abnormalities have been found to be while abnormalities in the periosteal ves- clues to underlying systemic disorders. -

Hair and Nails

Dermatology Hair and nails Paul Grinzi The hair and nails are often neglected in our dermatological Background assessments, as the sheer number and breadth of Hair and nails are elements of dermatology that can often conditions affecting the skin can seem overwhelming. This be omitted from the dermatological assessment. However, article focuses on common and important presentations to there are common and distressing hair and nail conditions that require diagnosis and management. general practice, including general and specific conditions affecting both hair and nails. Objective This article considers common and important hair and nail Hair presentations to general practice. General and specific conditions will be discussed. Structure and function Discussion Although hair no longer has any vital physiological function, its social Hair conditions may have significant psychological and psychological role is extremely important. Abnormalities of hair implications. This article considers assessment and often significantly affect self image and the associated psychological management of conditions of too much hair, hair loss or distress should not be ignored or dismissed. hair in the wrong places. It also considers the common nail Hair arises from the hair matrix (part of the epidermis) and is made conditions seen in general practice and provides a guide to up of modified keratin. In humans, hair follicles show intermittent diagnosis and management. activity. Over its lifecycle, each hair grows to a maximum length (this Keywords: nail diseases; hair diseases; hirsutism; phase is called anagen and can last 3–7 years), and is retained for a alopecia; onychomycosis; skin diseases short time without further growth (catagen, this phase lasts from a few days to 2 weeks), and is eventually shed and replaced (telogen, variable period) by a new anagen phase (Figure 1).