How Legacy and Inheritance Bear a Heavy Burden on Black Masculinity in a Raisin in the Sun, Barbershop, and Creed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movie Review: ‘Creed II’

Movie Review: ‘Creed II’ NEW YORK — Moviegoers under 33 take note: You had yet to be born when “Rocky IV,” the 1985 film that hovers in the background of the sports drama “Creed II” (MGM), was released. While viewers of any age will know what to expect from this latest extension of the durable franchise long before they buy a ticket, the tried and true, against-the-odds formula still works somehow. Early on in this chapter of the saga, Adonis Creed (Michael B. Jordan), with the help of his hard-driving trainer, Rocky Balboa (Sylvester Stallone), wins the world heavyweight championship. He also proposes to his live-in girlfriend, Bianca (Tessa Thompson), a singer who suffers from hearing loss. But the rise of Viktor Drago (Florian Munteanu), a rival Adonis feels compelled to take on, sets up an emotionally fraught match since the up-and-comer’s father and coach, Ivan (Dolph Lundgren), is the Russian fighter whose blows killed Adonis’ dad, Apollo, back in the Reagan era. (Rocky subsequently fought and beat Ivan.) Rocky continues to feel remorse over his opponent-turned-ally Apollo’s death and urges Adonis not to accept Viktor’s challenge, a stance that threatens to cause a breach in their close relationship. It’s a conflict Rocky can ill afford since the death of his wife and alienation from his son have left him emotionally isolated. He can still count on the loyal friendship of Apollo’s widow and Adonis’ adoptive mom, Mary Anne (Phylicia Rashad), however. Working from a script Stallone co-wrote with Juel Taylor, director Steven Caple Jr. -

Press Start Equip Level Up

CREED II (2018) | Moving Forward | BIBLE STUDY Facilitator Note: We encourage facilitators to take this Bible study and expound on it throughout the week, allowing it to be a springboard for deeper conversation and personal meditation. PRESS START Creed II continues the story started in 2015’s Creed, but the roots of that story began much earlier in 1976 in Rocky. For anyone keeping count, that makes this newest film the eighth in a long series that continues to inspire underdogs everywhere. Do you have a favorite film in the series so far? Have the new Creed films continued the legacy well in your opinion? With there being six Rocky films, how many more Creed stories do you think there could be? What else do you think lies ahead for Adonis Creed? EQUIP Adonis Creed and Rocky Balboa find themselves of different opinions after Adonis, the newly awarded heavyweight champion of the world, is called out and challenged by Viktor Drago, the son of former Russian boxer Ivan Drago. The elder Drago was single-handedly responsible for the death of Adonis’ father and Rocky’s friend Apollo Creed in Rocky IV, and this new challenge stems from decades of bad blood that followed. Adonis feels he must stand up and avenge his father (and satisfy his own pride) by taking Drago up on the match, but Rocky refuses to stand in the corner and watch another Creed die needlessly. Instead, Rocky, losing the only meaningful relationship in his life with Adonis, is left to spend his time at his restaurant and complain at home about a light in front of his house the city won’t fix. -

Cleaning Cash, Taking Names We Deliver!

AJW LANDSCAPING | 910-271-3777 Call us - we’ll bring the GREEN back to your property! Complete landscape design Mowing - Pruning - Mulching- Stone borders & walls March 2 - 8, 2019 Licensed - Insured Cleaning We keep it cooking! cash, taking names Christina Hendricks stars in “Good Girls” We Deliver! Pricing Plans Available 910 276 7474 | 877 829 2515 12780 S Caledonia Rd, Laurinburg, NC 28352 serving Scotland County and surrounding areas Joy Jacobs, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street, Laurinburg NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, March 2, 2019 — Laurinburg Exchange Calling the shots: Criminal suburban moms are back in season 2 of ‘Good Girls’ By Joy Doonan ter “Good Girls” first premiered, its them, and realize that no one can TV Media anxiously anticipated second arrives dig them out of their respective this week, picking up where season holes but themselves. They plot to howrunner Jenna Bans has been 1 left us hanging. The first episode of rob the supermarket where Annie Spraised for her forthright portray- season 2 airs Sunday, March 3, on works, but when they end up with al of fed up, angry women in “Good NBC. far more money than they anticipat- Girls.” Bans came up with the idea The titular “good girls” are three ed, they find themselves in the mid- for the NBC dramedy during the earnest working moms who are at dle of a money-laundering opera- 2016 U.S. election, and she wanted the ends of their ropes, struggling tion run by local gangsters. to capture the pervasive sense of in- with financial strain and a host of Though the raucous intrigue of justice that many people seemed to personal troubles. -

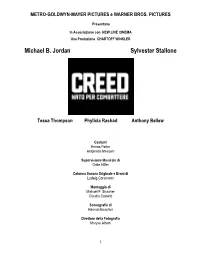

Michael B. Jordan Sylvester Stallone

METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER PICTURES e WARNER BROS. PICTURES Presentano In Associazione con NEW LINE CINEMA Una Produzione CHARTOFF WINKLER Michael B. Jordan Sylvester Stallone Tessa Thompson Phylicia Rashad Anthony Bellew Costumi Emma Potter Antoinette Messam Supervisione Musicale di Gabe Hilfer Colonna Sonora Originale e Brani di Ludwig Goransson Montaggio di Michael P. Shawver Claudia Castello Scenografie di Hannah Beachler Direttore della Fotografia Maryse Alberti 1 Produttore Esecutivo Nicolas Stern Prodotto da Irwin Winkler, p.g.a Robert Chartoff, p.g.a Charles Winkler William Chartoff David Winkler Kevin King-Templeton, p.g.a. Sylvester Stallone, p.g.a Soggetto di Ryan Coogler Sceneggiatura di Ryan Coogler & Aaron Covington Diretto da Ryan Coogler Distribuzione WARNER BROS. PICTURES Durata: 132 minuti Uscita italiana: 14 Gennaio 2016 I materiali sono a disposizione sul sito “Warner Bros. Media Pass”, al seguente indirizzo: https://mediapass.warnerbros.com sito: www.warnerbros.it/scheda-film/genere-azione/creed-nato-combattere FB: www.facebook.com/CreedIlFilm Ufficio Stampa Warner Bros. Entertainment Italia US Ufficio Stampa Riccardo Tinnirello Alessandro Russo [email protected] [email protected] Emanuela Semeraro Valerio Roselli [email protected] [email protected] Cinzia Fabiani [email protected] Antonio Viespoli [email protected] Egle Mugno [email protected] 2 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures, Warner Bros. Pictures e New Line Cinema presentano “Creed”, del regista pluripremiato Ryan Coogler, che torna a lavorare con la star del suo “Prossima fermata Fruitvale Station”, Michael B. Jordan, nel ruolo del figlio di Apollo Creed, ed esplora un nuovo capitolo della storia di “Rocky”, con il candidato agli Oscar Sylvester Stallone nel suo ruolo storico. -

To Download The

Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTE VEDRA April 23, 2020 RNot yourecor average newspaper, not your average reader Volume 51, No. 25 der 75 cents PonteVedraRecorder.com BACK TO THE BEACH Beachgoers take to Mickler’s Beach on Tuesday after St. Johns County reopened the beaches for limited hours. Photo by Don Coble Read more on page 3 MORE Tips for dealing with the stress of INSIDE: the COVID-19 pandemic, page 7 Garden centers seeing surge of business during crisis, Area restaurant takeout and What’s Available NOW On page 10 delivery guide, page 14 INSIDE: CHECK IT OUT! “Movie: Hotel Artemis” “Movie: Creed II” “Upload” The eighth entry in the “Rocky” film series, “The Office” mentor Greg Daniels took The Recorder’s Entertainment “Movie: Rambo: Last Blood” Drew Pearce wrote and made his feature directorial debut with this 2018 thriller director Steven Caple Jr.’s 2018 sequel to several decades to hatch this sci-fi comedy Staying Healthy: Sylvester Stallone’s Vietnam veteran returns set in a dystopian near-future Los Angeles, 2015’s “Creed” finds Michael B. Jordan series that imagines a future where 11 years after “Rambo III” for this 2019 where Jean Thomas (Jodie Foster), a severely returning to his role as Adonis Creed. The hologram phones, 3D food printers and effort that finds the retired, PTSD-ridden rising young boxer encounters a powerful automated grocery stores are the norm and agoraphobic nurse, runs a secret facility that character heading off to Mexico after his adversary in the ring: Viktor Drago (Florian humans can choose to upload themselves caters exclusively to criminals (house rules housekeeper’s granddaughter is kidnapped “Big Nasty” Munteanu), the son of Russian to a virtual afterlife when they’re near include “no killing of other guests”). -

What Is Your “Why?" UNK COMMUNICATION the Nebraska State Normal School to Kearney

OPINION, PAGE 3: The Rocky Balboa film series continues with the antelope "Creed" Volume 117, Issue 15 | 2.3.16 | www.unkantelope.com 111-year anniversary inspires 2016 events What is your “why?" UNK COMMUNICATION the Nebraska State Normal School to Kearney. Davis encourages all to “UNK Perspectives: 111 and 25” Events Jump ahead to September 1905 March 1 - Lecture “Kearney’s Beginning,” – 111 years ago – when new Normal reach for their best 4 p.m., Chancellor Douglas A. Kristensen, School president A.O. Thomas took over SHELBY CAMERON fall classes in the new Administration Fine Arts Building Recital Hall, followed by Antelope Staff premiere of “Perspectives” Exhibition and Building. It had temporary stairs, lacked window glass, and required steam reception, Calvin T. Ryan Library On Thursday, Jan. 28, the Office of engines to deliver heat until the heating April 6 - “A Century in the Making,” 7 Multicultural Affairs: The Social Justice plant was completed. p.m. film and panel, World Theatre League presented “The Life, The Legacy of Could the Nebraska Legislature July 1 - “25 Years” faculty/staff Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.” by Aaron Davis and president Thomas know that nearly celebration and breakfast, under the Yanney at the Nebraskan Student Union Ponderosa 85 years later, in 1989, another historic bell tower Room. legislative battle would erupt over the fate Sept. 1 - Student artwork exhibition Over 80 gathered to hear Davis speak of then-Kearney State College to become September TBD - “111 & 25” the “bald truth” about empowerment and part of the University of Nebraska? Celebration Dinner what it means to perform like champions The year 2016 marks historic each and every day. -

Michael B. Jordan Sylvester Stallone

METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER PICTURES e WARNER BROS. PICTURES Presentano In Associazione con NEW LINE CINEMA Una Produzione CHARTOFF WINKLER Michael B. Jordan Sylvester Stallone Tessa Thompson Phylicia Rashad Anthony Bellew Costumi Emma Potter Antoinette Messam Supervisione Musicale di Gabe Hilfer Colonna Sonora Originale e Brani di Ludwig Goransson Montaggio di Michael P. Shawver Claudia Castello Scenografie di Hannah Beachler Direttore della Fotografia Maryse Alberti 1 Produttore Esecutivo Nicolas Stern Prodotto da Irwin Winkler, p.g.a Robert Chartoff, p.g.a Charles Winkler William Chartoff David Winkler Kevin King-Templeton, p.g.a. Sylvester Stallone, p.g.a Soggetto di Ryan Coogler Sceneggiatura di Ryan Coogler & Aaron Covington Diretto da Ryan Coogler Distribuzione WARNER BROS. PICTURES Durata: 132 minuti Uscita italiana: 14 Gennaio 2016 I materiali sono a disposizione sul sito “Warner Bros. Media Pass”, al seguente indirizzo: https://mediapass.warnerbros.com sito: www.warnerbros.it/scheda-film/genere-azione/creed-nato-combattere FB: www.facebook.com/CreedIlFilm Ufficio Stampa Warner Bros. Entertainment Italia US Ufficio Stampa Riccardo Tinnirello Alessandro Russo [email protected] [email protected] Emanuela Semeraro Valerio Roselli [email protected] [email protected] Cinzia Fabiani [email protected] Antonio Viespoli [email protected] Egle Mugno [email protected] 2 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures, Warner Bros. Pictures e New Line Cinema presentano “Creed”, del regista pluripremiato Ryan Coogler, che torna a lavorare con la star del suo “Prossima fermata Fruitvale Station”, Michael B. Jordan, nel ruolo del figlio di Apollo Creed, ed esplora un nuovo capitolo della storia di “Rocky”, con il candidato agli Oscar Sylvester Stallone nel suo ruolo storico. -

School Newsletter 2.Pages

The Little Bulldog Newspaper Staff Editors: Hanna World News Buczkowski-Levy, Emily Rubenstein The Sweden Ice Hotel Assistant Editors: Nathan Chen, By Nela Sahady Amanda Brille The Swedish ice hotel is built each year from December to Reporters: Alexander Bonham, April out of snow and ice from the nearby Torne River. it Alicia Wang, Alisha features bars and hotel rooms just as you would see in a Schruefer, Amanda regular hotel. The ice hotel has no bathrooms, but there is a Brille, Anneke warm building nearby with bathrooms. The passageway Lewis, Bennett into the hotel has a beautiful chandelier made entirely out of Richman, Brianna Zigah, Charles ice. This amazing hotel even features a church and a bar, Buckles, Clarke and can fit over 100 guests in this suite. Each year when this Norman, Dilan ice hotel is rebuilt, it highlights many different things. Mendiratta, Dillon Someday I would like to stay there. Malkani, Edward Stewart, Elizabeth Martin, Ella Rosoff, GLOBAL WARMING: OUR PLANET IS Emily Rubenstein, Ethan Robinson, IN HOT WATER Hanna Buczkowski- Levy, Hayden By: Hayden Chaffin Chaffin, Jack Global Warming is a serious problem for some scientists Sandi, Jessica and is something we should all think about even if it is Gates, Khumo scary. Newman, Maeve Zimmer, Maison Global Warming is “the rise of temperatures throughout Metro, Mariam El- the Earth” and scientists say that it is caused by burning too Taguri, McKenzie much fossil fuel and more greenhouse gases being released Suggs, Nela Sahady, Reese into the environment. Fossil fuel is what you call buried Narcisenfeld, materials that are then turned into oil, coal or natural gases Samantha Pepper, or heavy oils. -

Creed Boxing Movie Iso Download Real Boxing 2 ROCKY

Creed Boxing Movie ISo Download Real Boxing 2 ROCKY. Real Boxing 2 ROCKY is a boxing Simulator duel. Immerse yourself in a new reality — virtual boxing fights! The game is created based on the eponymous movie — Creed is the sequel to the epic about legendary Boxer Rocky Balboa. The hero of this sports history — Adonis Johnson (son of Apollo Creed) legendary rival Rocky Balboa. Your task: hold the young Adonis on career from street fighter, to champion at Olympus boxing world. You have to coach Johnson, hold rating fights, go mini-games and throwing challenges friends and enemies — players worldwide. The Office hero: Learn how to make hooks and uppercuts, Jba ' and serial attacks, protected and "dirty" methods — all, that should send your opponents in the knockout. You also have to go through hundreds of mini-games (MMO-battles) with rivals, that will be available only for a limited time. Hurry to compete with them, to take away their titles and special gear — it will pay on each following more complex level games. In order to build a successful career to establish his own style of fighting: develop speed and endurance, reaction and will to win! Learn techniques and combinations of them-they will transform your fighter in a crushing machine at the ring. Every victory and achievement you will get access to unique equipment, able to improve physical abilities your character. Personalize your Boxer: Select the body mass, facial features, top rack and other features. Participate in mock duels, invite your friends, to find out who the King of the ring. -

Creed Workout Day 1: Pull Strength Workout Exercise Sets Reps Warm Up: Stretch, SMR, Perform 5 - 10 Mins of Jump Roping

THE TOOLS YOU NEED TO BUILD THE BODY YOU WANT® Store Workouts Diet Plans Expert Guides Videos Tools ADONIS CREED INSPIRED WORKOUT: SHRED FAT LIKE A CONTENDER Train like Rocky Balboa’s protege, Adonis Main Goal: Lose Fat Equipment: Barbell, Bodyweight, Creed, with this workout program that mixes Training Level: Advanced Cables, Dumbbells, Machines weight training & cardio for a balanced muscle building approach. Program Duration: 8 Weeks Targert Gender: Male Days Per Week: 6 Days Author: Josh England Link to Workout: https://www.muscleandstrength.com/ Time Per Workout: 75-90 Mins workouts/creed-workout-program Creed Workout Day 1: Pull Strength Workout Exercise Sets Reps Warm Up: Stretch, SMR, Perform 5 - 10 Mins of Jump Roping. 1. Deadlift 4 3 - 5 2. Bent Over Row 4 5 3. Weighted Chin Up 3 6 4. Dumbbell Row 3 8 5. Face Pull 3 12 6. Barbell Curl 4 10 Cardio: Perform cardio intervals for 15-45 minutes. If you’re trying to go the true Creed route, do some heavy bag intervals, speed bag intervals, or sparring. Creed Workout Day 2: Push Strength Workout Exercise Sets Reps Warm Up: Stretch, SMR, Perform 5 - 10 Mins of Jump Roping. 1. Bench Press 4 3 - 5 2. Seated Military Press 4 5 3. Weighted Dips 3 6 4. Pec Dec Fly 3 12 5. Lateral Raise 3 12 6. Tricep Rope Extension 4 12 Cardio: Perform cardio intervals for 15-45 minutes. If you’re trying to go the true Creed route, do some heavy bag intervals, speed bag intervals, or sparring. Creed Workout Day 3: Legs Strength Workout Exercise Sets Reps Warm Up: Stretch, SMR, Perform 5 - 10 Mins of Jump Roping. -

Creed 2 Russian Translation

Creed 2 russian translation Continue CAPTAIN CINEMAXX SEEN - CREED II - SPOILERS - Translation flavi LE GUENTron : Legacy, Transporter : Legacy, Jason Bourne : Legacy, Jigsaw, Legacy Saga never shone with its originality and often had big box office furnaces, however, Creed : The legacy of Rocky Balboa, if it does not have huge financial success (173 million dollars collected in the world, but only with a budget of 35 million is not a failure compared to his previous rivals. And here we are with a sequel, soberly called Creed II (don't overdo it!), the second opus where Adonis Creed, will encounter the son of the man who killed his father. Thin! In production, Stephen Capble Jr., Hollywood's new favorite since the first feature film adored by critics in 2016, Earth. With this success, it's formalized, next year, to pick up this new Opus Creed, while director Ryan Coogler himself has been busy on the Marvel Studios side with Black Panther.On the screen side, Jewel Taylor and Sylvester Stallone, succeeds Ryan Coogler (also screenwriter) and Aaron Covington, and the film's problem may lie here. While Stephen Capble Jr.'s production is pretty good, Creed II suffers from an all-too-simple, too-classic script, with no real twists to surprise the viewer and thus give a whole less smooth character: a story of revenge, pride and arrogance of a hero that costs him victory, existential issues related to fatherhood and confrontation with family, coach and student, who are confused but ultimately reconciled. , under the high tension that the hero wins by humiliating his opponent on his land. -

Nato Per Combattere Di Ryan Coogler

Creed – Nato per combattere di Ryan Coogler. Con Michael B. Jordan, Sylvester Stallone, Tessa Thompson, Phylicia Rashad, Tony Bellew USA 2015 Los Angeles, Adonis “Donnie” Johnson (Alex Henderson) è un ragazzino difficile: passa dall’orfanotrofio a famiglie affidatarie e al riformatorio, dove viene spesso isolato perché fa a botte con gli altri ragazzi. Lui non lo sa ma è il figlio naturale di Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers) e la sua vedova, Mary Anne (Rashad) decide di adottarlo. Qualche anno dopo Donnie Creed (Jordan) è un brillante manager di una società finanziaria ma, appena può, scappa a Tijuana a cimentarsi in incontri di boxe non ufficiali, vincendone 16 per k.o. e, proprio quando riceve una prestigiosa promozione, si dimette dal lavoro per seguire la sua vocazione al pugilato. Marie Anne tenta di dissuaderlo, minacciando di non vederlo più, ma lui parte per Filadelfia e va al ristorante Adrian’s di Rocky (Stallone), per chiedergli, in nome della vecchia amicizia con il padre, di allenarlo ma l’ex-campione rifiuta: orma è fuori dal mondo del pugilato. Lui comincia così ad allenarsi da solo nella palestra di Mickey – l’ex- allenatore (Burgess Meredith) di Rocky – gestita ora da Pete Sporino (Ritchie Coster), che allena personalmente il figlio Leo “The Lion” (Gabe Rosado), sul quale fonda molte speranze. Adonis va a vivere in un appartamento in cui, al piano di sotto, vive Bianca (Thompson) una cantante affetta da perdita progressiva dell’udito, con la quale di lì a poco si fidanzerà. Alle mille insistenze del ragazzo, Rocky torna alla palestra di Mickey e, dopo aver rifiutato la proposta di Pete di allenare Leo, dice ad Adonis che, se mostrerà il giusto impegno, si occuperà di lui.