A Work in Progress: the Corrections and Conditional Release Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter to Prime Minister Paul Martin, 29 September 2004

September 29, 2004 The Right Honourable Paul Martin Prime Minister of Canada 80 Wellington Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A2 RE: An Open Letter to Prime Minister Paul Martin Calling for the Cancellation of the Debts of the Poorest Countries. Dear Prime Minister, Perhaps more than any other G•7 leader, you are aware of the importance of debt cancellation for impoverished countries, and the failures of past strategies to address the debt issue. Despite important gains secured by current debt relief strategies, poor countries still spend more on debt service than on health and education. Countries in Africa continue to pay more for debt servicing than they receive in development assistance, and in most cases this amount is greater than their budgets for health and education combined. As you know, in the coming days the world's richest countries may be set to take a dramatic and necessary step to cancel the debt of some of the poorest countries. We call on the Government of Canada to ensure that the lessons of past efforts are incorporated in new plans, and that the political will is shown by G•7 leaders to ensure that poor countries are finally able to get off of the debt treadmill. We call on Canada to support the immediate and unconditional cancellation of 100% of the debts owed by all low•income countries to multilateral financial institutions; recognition that neither the people of Iraq, nor citizens of other countries formerly ruled by dictators, should be obliged to repay odious debts; that countries who receive debt cancellation be free to implement their own national development strategies with no strings attached to cancellation; and, credit on accessible terms for the world's poorest countries. -

Core 1..146 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 140 Ï NUMBER 098 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, May 13, 2005 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 5957 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, May 13, 2005 The House met at 10 a.m. Parliament on February 23, 2005, and Bill C-48, an act to authorize the Minister of Finance to make certain payments, shall be disposed of as follows: 1. Any division thereon requested before the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, shall be deferred to that time; Prayers 2. At the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, all questions necessary for the disposal of the second reading stage of (1) Bill C-43 and (2) Bill C-48 shall be put and decided forthwith and successively, Ï (1000) without further debate, amendment or deferral. [English] Ï (1010) MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE The Speaker: Does the hon. government House leader have the The Speaker: I have the honour to inform the House that a unanimous consent of the House for this motion? message has been received from the Senate informing this House Some hon. members: Agreed. that the Senate has passed certain bills, to which the concurrence of this House is desired. Some hon. members: No. Mr. Jay Hill (Prince George—Peace River, CPC): Mr. -

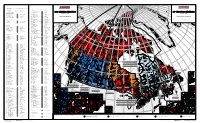

Map of Canada, Official Results of the 38Th General Election – PDF Format

2 5 3 2 a CANDIDATES ELECTED / CANDIDATS ÉLUS Se 6 ln ln A nco co C Li in R L E ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED de ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED C er O T S M CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU C I bia C D um CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU É ol C A O N C t C A H Aler 35050 Mississauga South / Mississauga-Sud Paul John Mark Szabo N E !( e A N L T 35051 Mississauga--Streetsville Wajid Khan A S E 38th GENERAL ELECTION R B 38 ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE C I NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR 35052 Nepean--Carleton Pierre Poilievre T A I S Q Phillip TERRE-NEUVE-ET-LABRADOR 35053 Newmarket--Aurora Belinda Stronach U H I s In June 28, 2004 E T L 28 juin, 2004 É 35054 Niagara Falls Hon. / L'hon. Rob Nicholson E - 10001 Avalon Hon. / L'hon. R. John Efford B E 35055 Niagara West--Glanbrook Dean Allison A N 10002 Bonavista--Exploits Scott Simms I Z Niagara-Ouest--Glanbrook E I L R N D 10003 Humber--St. Barbe--Baie Verte Hon. / L'hon. Gerry Byrne a 35056 Nickel Belt Raymond Bonin E A n L N 10004 Labrador Lawrence David O'Brien s 35057 Nipissing--Timiskaming Anthony Rota e N E l n e S A o d E 10005 Random--Burin--St. George's Bill Matthews E n u F D P n d ely E n Gre 35058 Northumberland--Quinte West Paul Macklin e t a s L S i U a R h A E XEL e RÉSULTATS OFFICIELS 10006 St. -

Letter to Prime Minister Paul Martin August 2005

August 18, 2005 The Right Honourable Paul Martin Prime Minister of Canada Office of the Prime Minister 80 Wellington Street Ottawa, ON K1A 0A2 Dear Prime Minister: Re: Canada's contribution to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS TB and Malaria (GFATM) As a coalition of international development organizations, international humanitarian organizations, AIDS service organizations, trade unions, faith-based groups and human rights organizations, we are writing to encourage you to continue showing Canada's commitment to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS TB and Malaria (GFATM) by making a generous pledge at the GFATM Replenishment Conference taking place in London on September 5 and 6, 2005. The GFATM is an innovative financing mechanism that has shown good results in a very short period of time. Programs funded by the GFATM are delivering an expansion of prevention and treatment services for HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis. To date, 130,000 people are receiving treatment for AIDS; 385,000 people have been treated for tuberculosis, and 1.35 million bed nets have been distributed or re-impregnated to prevent malaria. This is clearly only the beginning. The global fund must be adequately financed if the long awaited scale-up of treatment and prevention of these diseases is going to become a reality. The GFATM has estimated that it requires about US$2.9 billion in 2006 and US$4.2 in 2007 to meet existing commitments and respond to new project requests. This is significantly more than what was required in the early rounds of funding, partly because there is a need to dramatically scale up the response to the three diseases, and partly because the Global Fund is now faced with renewing successful grants approved earlier at the same time as it is approving new proposals. -

Leadership by Design to Unveil One Place to Look, OLBA's On-Line

For and about members of the ONTARIO LIBRARY BOARDS’ ASSOCIATION InsideOLBA WINTER 2008 NO. 21 ISSN 1192 5167 Leadership by Design to unveil One Place to Look, OLBA’s on-line library for trustees he Ontario Library everything easier to use. One Boards‘Association is Place to Look is the result of ready to unveil the latest research done by Margaret component of its four-year pro- Andrewes and Randee Loucks gram, Leadership by Design. in which trustees said they TThe project’s on-line library wanted to look for resources in for trustees, One Place to Look, one place and that the search is ready for launch at the 2008 needed to be as simple as possi- Super Conference. OLBA ble. Council has seen the test ver- Many trustees with little on- sion and were thrilled with line experience were particular- what they saw. You will be, too. ly anxious that access to trustee materials be simple. These One Place to Look builds findings informed the develop- on Cut to the Chase ment of One Place to Look, our Cut to the Chase is the on-line library for trustees. durable, laminated four-page fold-out quick reference guide Your Path to Library to being a trustee. This was the Leadership is the Key damental responsibilities in years by the Library Develop- first element in the Leadership Borrowing the name from achieving effective leadership ment Training Program spear- by Design project. Since the the Ontario library communi- and sound library governance. headed by the Southern Ontario final version of Cut to the ty’s 1990 Strategic Plan that The “Your Path to Library Library Service in combination Chase was delivered to all saw the beginning of more Leadership ” chart on the back with the Ontario Library library boards in Ontario, the intensive focus on board devel- of Cut to the Chase is your key Service-North and the Ontario response has been excellent. -

Final Report from the Conference

Final Report: Conférence de Montréal with the Haitian Diaspora December 10-11, 2004 ENGLISH SUMMARY Canadian Foundation for the Americas (FOCAL) Canadian Foundation for the Americas Fondation canadienne pour les Amériques www.focal.ca 14 janv. 05 Rapport Final: de la Conférence de Montréal avec la Diaspora haïtienne Programme Agenda Conférence de Montréal avec la Diaspora haïtienne Vendredi 10 décembre 17:00-19:00 Inscription des participants avec choix des ateliers 17:45-18:00 Accréditation des médias 19:00-21:00 Ouverture de la Conférence – Allocutions • Ministre de la Coopération internationale, l’honorable Aileen Carroll, co-présidente de la Conférence • Ministre responsable de la Francophonie, l’honorable Jacques Saada, co-président de la Conférence • Ministre des Affaires Etrangers, l’honorable Pierre Pettigrew (via vidéo) • Maire de Montréal, son honneur M. Gérald Tremblay • Présentation du Ministre haïtien des Haïtiens vivant à l’étranger, Son Excellence M. Alix Baptiste Suivi d’une réception Samedi 11 décembre 09:00-09:15 Inauguration officielle de la Conférence par le Premier Ministre du Canada, le très honorable Paul Martin 09:15-09:30 Allocution du Premier Ministre d’Haïti, Son Excellence M. Gérard Latortue 09:30-09:45 Mot de bienvenue par les Ministres Aileen Carroll et Jacques Saada 09:45-10:15 Présentation sur la situation présente en Haïti Ambassadeur Juan Gabriel Valdés Représentant spécial et chef de la Mission des Nations Unies pour la stabilisation en Haïti (MINUSTAH) Période de questions et réponses 10:15-10:50 Le Cadre de Coopération Intérimaire (CCI) et l’engagement du Canada • Présentation du CCI - Son Excellence M. -

Women As Executive Leaders: Canada in the Context of Anglo-Almerican Systems*

Women as Executive Leaders: Canada in the Context of Anglo-Almerican Systems* Patricia Lee Sykes American University Washington DC [email protected] *Not for citation without permission of the author. Paper prepared for delivery at the Canadian Political Science Association Annual Conference and the Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences, Concordia University, Montreal, June 1-3, 2010. Abstract This research identifies the obstacles and opportunities women as executives encounter and explores when, why, and how they might engender change by advancing the interests and enhancing the status of women as a group. Various positions of executive leadership provide a range of opportunities to investigate and analyze the experiences of women – as prime ministers and party leaders, cabinet ministers, governors/premiers/first ministers, and in modern (non-monarchical) ceremonial posts. Comparative analysis indicates that the institutions, ideology, and evolution of Anglo- American democracies tend to put women as executive leaders at a distinct disadvantage. Placing Canada in this context reveals that its female executives face the same challenges as women in other Anglo countries, while Canadian women also encounter additional obstacles that make their environment even more challenging. Sources include parliamentary records, government documents, public opinion polls, news reports, leaders’ memoirs and diaries, and extensive elite interviews. This research identifies the obstacles and opportunities women as executives encounter and explores when, why, and how they might engender change by advancing the interests and enhancing the status of women. Comparative analysis indicates that the institutions, ideology, and evolution of Anglo-American democracies tend to put women as executive leaders at a distinct disadvantage. -

Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Fuchs, Andreas; Richert, Katharina Working Paper Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving? Discussion Paper Series, No. 604 Provided in Cooperation with: Alfred Weber Institute, Department of Economics, University of Heidelberg Suggested Citation: Fuchs, Andreas; Richert, Katharina (2015) : Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving?, Discussion Paper Series, No. 604, University of Heidelberg, Department of Economics, Heidelberg, http://dx.doi.org/10.11588/heidok.00019769 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127421 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von -

Debates of the Senate

CANADA Debates of the Senate 1st SESSION . 38th PARLIAMENT . VOLUME 142 . NUMBER 50 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Thursday, April 14, 2005 ^ THE HONOURABLE DANIEL HAYS SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates and Publications: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 996-0193 Published by the Senate Available from PWGSC ± Publishing and Depository Services, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S5. Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1037 THE SENATE Thursday, April 14, 2005 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the chair. make my apology when he asked for it. However, I did so at the earliest opportunity. Furthermore, the error for which I was Prayers. asked to apologize was made during Inquiries, which allows for full and open debate. Senator Austin did not ask for an apology then, nor did he ask for one later in the day on March 23, during SENATORS' STATEMENTS the budget, inquiry when every one of the senators opposite could have entered the debate. THE SENATE Honourable senators, Senator Austin expressed shame that REMARKS WITHDRAWN false statements and ridiculous portrayals of Canada had taken place in front of the delegates in the chamber from Malaysia. I Hon. Gerry St. Germain: Honourable senators, I rise today to agree it is a shame, but I did not cause that shame. The party of withdraw the remarks I made during Question Period yesterday. the government that the members opposite belong to caused the Hon. Jack Austin (Leader of the Government): Honourable shame. senators, I thank Senator St. Germain. -

Exploring Canada's Relations with the Countries of The

HOUSE OF COMMONS CANADA EXPLORING CANADA’S RELATIONS WITH THE COUNTRIES OF THE MUSLIM WORLD REPORT OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE Bernard Patry, M.P. Chair March 2004 The Speaker of the House hereby grants permission to reproduce this document, in whole or in part for use in schools and for other purposes such as private study, research, criticism, review or newspaper summary. Any commercial or other use or reproduction of this publication requires the express prior written authorization of the Speaker of the House of Commons. If this document contains excerpts or the full text of briefs presented to the Committee, permission to reproduce these briefs, in whole or in part, must be obtained from their authors. Also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire: http://www.parl.gc.ca Available from Communication Canada — Publishing, Ottawa, Canada K1A 0S9 EXPLORING CANADA’S RELATIONS WITH THE COUNTRIES OF THE MUSLIM WORLD REPORT OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE Bernard Patry, M.P. Chair March 2004 STANDING COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE CHAIR Bernard Patry VICE-CHAIRS Stockwell Day Hon. Diane Marleau MEMBERS Stéphane Bergeron Hon. Dan McTeague Hon. Scott Brison Deepak Obhrai Bill Casey Charlie Penson Hon. Art Eggleton Beth Phinney Brian Fitzpatrick Karen Redman Francine Lalonde Raymond Simard Paul Macklin Bryon Wilfert Alexa McDonough OTHER MEMBERS WHO PARTICIPATED IN THIS STUDY DURING THE 2ND SESSION OF THE 37TH PARLIAMENT Murray Calder -

2004 Sea Island Final Compliance Report

Sea Island Final Compliance Results June 10, 2004, to June 1, 2005 Final Report July 1, 2005 Professor John Kirton, Dr. Ella Kokotsis, Anthony Prakash Navanellan and the University of Toronto G8 Research Group <www.g8.utoronto.ca> [email protected] Please send comments to the G8 Research Group at [email protected]. <www.g8.utoronto.ca> Table of Contents Preface........................................................................................................................................3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................4 Table A: 2004-2005 Sea Island Final Compliance Scores*......................................................8 Table B: 2004 Sea Island Interim Compliance Scores*............................................................9 Table C: G8 Compliance Assessments by Country, 1996-2005 .............................................10 Broader Middle East & North Africa Initiative: Forum for the Future / Democracy Assistance Dialogue............................................................11 Broader Middle East & North Africa Initiative: Iraqi Elections Support....................................23 World Economy........................................................................................................................42 Trade: WTO Doha Development Agenda..................................................................................56 Trade: Technical Assistance......................................................................................................64 -

Computational Identification of Ideology In

Computational Identification of Ideology in Text: A Study of Canadian Parliamentary Debates Yaroslav Riabinin Dept. of Computer Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 3G4, Canada February 23, 2009 In this study, we explore the task of classifying members of the 36th Cana- dian Parliament by ideology, which we approximate using party mem- bership. Earlier work has been done on data from the U.S. Congress by applying a popular supervised learning algorithm (Support Vector Ma- chines) to classify Senatorial speech, but the results were mediocre unless certain limiting assumptions were made. We adopt a similar approach and achieve good accuracy — up to 98% — without making the same as- sumptions. Our findings show that it is possible to use a bag-of-words model to distinguish members of opposing ideological classes based on English transcripts of their debates in the Canadian House of Commons. 1 Introduction Internet technology has empowered users to publish their own material on the web, allowing them to make the transition from readers to authors. For example, people are becoming increasingly accustomed to voicing their opinions regarding various prod- ucts and services on websites like Epinions.com and Amazon.com. Moreover, other users appear to be searching for these reviews and incorporating the information they acquire into their decision-making process during a purchase. This indicates that mod- 1 ern consumers are interested in more than just the facts — they want to know how other customers feel about the product, which is something that companies and manu- facturers cannot, or will not, provide on their own.