“Food Security and Cross-Border Trade”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

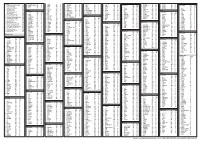

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Report of the Technical Committee Om

REPORT OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS FOR THE APPLICATION OF SHARIA IN KATSINA STATE January 2000 Contents: Volume I: Main Report Chapter One: Preliminary Matters Preamble Terms of Reference Modus Operandi Chapter Two: Consideration of Various Sections of the Constitution in Relation to Application of Sharia A. Section 4(6) B. Section 5(2) C. Section 6(2) D. Section 10 E. Section 38 F. Section 275(1) G. Section 277 Chapter Three: Observations and Recommendations 1. General Observations 2. Specific Recommendations 3. General Recommendations Conclusion Appendix A: List of all the Groups, Associations, Institutions and Individuals Contacted by the Committee Volume II: Verbatim Proceedings Zone 1: Funtua: Funtua, Bakori, Danja, Faskari, Dandume and Sabuwa Zone 2: Malumfashi: Malumfashi, Kafur, Kankara and Musawa Zone 3: Dutsin-Ma: Dutsin-Ma, Danmusa, Batsari, Kurfi and Safana Zone 4: Kankia: Kankia, Ingawa, Kusada and Matazu Zone 5: Daura: Daura, Baure, Zango, Mai’adua and Sandamu Zone 6: Mani: Mani, Mashi, Dutsi and Bindawa Zone 7: Katsina: Katsina, Kaita, Rimi, Jibia, Charanchi and Batagarawa 1 Ostien: Sharia Implementation in Northern Nigeria 1999-2006: A Sourcebook: Supplement to Chapter 2 REPORT OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON APPLICATION OF SHARIA IN KATSINA STATE VOLUME I: MAIN REPORT CHAPTER ONE Preamble The Committee was inaugurated on the 20th October, 1999 by His Excellency, the Governor of Katsina State, Alhaji Umaru Musa Yar’adua, at the Council Chambers, Government House. In his inaugural address, the Governor gave four point terms of reference to the Committee. He urged members of the Committee to work towards realising the objectives for which the Committee was set up. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Analysis of Crime in Katsina Metropolitan Area, Katsina State

ANALYSIS OF CRIME IN KATSINA METROPOLITAN AREA, KATSINA STATE, NIGERIA BY Ahmed Barde, ABDULLAHI B.Sc (A.B.U. Zaria) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN REMOTE SENSING AND GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION SYSTEM DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA NOVEMBER, 2018 ANALYSIS OF CRIME IN KATSINA METROPOLITAN AREA, KATSINA STATE, NIGERIA BY Ahmed Barde, ABDULLAHI B.Sc (A.B.U. Zaria) P16PSGS8540 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN REMOTE SENSING AND GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION SYSTEM DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA NOVEMBER, 2018 ii DECLARATION I declare that this project research titled‟ “ANALYSIS OF CRIME IN KATSINA METROPOLITAN AREA, KATSINA STATE NIGERIA” Wasconducted by me under the supervision of DR. A.K Usman and DR.B. AkpuDepartment of Geography and Environmental Management and it is a record of my own work and has not been submitted for the award of Masters Degree, diploma or any other qualification in any other institution. All information and excerpts from the work of any other has been acknowledged by means of references. ABDULLAHI AHMED BARDE ______________________ ___________________ Signature Date iii CERTIFICATION This dissertation entitled “ANALYSIS OF CRIME IN KATSINA METROPOLITAN AREA, KATSINA STATE NIGERIA” meets the regulations governing the award of masters‟ degree of Remote Sensing and GIS of Ahmadu Bello University and approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. -

IOM Nigeria DTM Flash Report NCNW 26 June 2020

FLASH REPORT: POPULATION DISPLACEMENT DTM North West/North Central Nigeria. Nigeria 22 - 26 JUNE 2020 Aected Population: Casualties: Movement Trigger: 2,349 Individuals 3 Individuals Armed attacks OVERVIEW Maikwama 219 The crisis in Nigeria’s North Central and North West zones, which involves long-standing Dandume tensions between ethnic and linguis�c groups; a�acks by criminal groups; and banditry/hirabah (such as kidnapping and grand larceny along major highways) led to fresh wave of popula�on displacement. Kaita Mashi Mai'adua Jibia Shinkafi Katsina Daura Zango Dutsi Batagarawa Mani Safana Latest a�acks affected 2,349 individuals, includ- Zurmi Rimi Batsari Baure Maradun Bindawa Kurfi ing 18 injuries and 3 fatali�es, in Dandume LGA Bakura Charanchi Ingawa Jigawa Kaura Namoda Sandamu Katsina Birnin Magaji Kusada Dutsin-Ma Kankia (Katsina) and Bukkuyum LGA (Zamfara) between Talata Mafara Bungudu Matazu Dan Musa 22 - 26 June, 2020. The a�acks caused people to Gusau Zamfara Musawa Gummi Kankara flee to neighboring locali�es. Bukkuyum Anka Tsafe Malumfashi Kano Faskari Kafur Gusau Bakori A rapid assessment was conducted by field staff Maru Funtua Dandume Danja to assess the impact on people and immediate Sabuwa needs. ± GENDER (FIG. 1) Kaduna X Affected PopulationPlateau 42% Kyaram 58% Male State Bukkuyum 2,130 Female Federal Capital Territory LGA Nasarawa Affected LGAs The map is for illustration purposes only. The depiction and use of boundaries, geographic names and related data shown are not warranted to be error free nor do they imply judgment on the legal status of any territory, or any endorsement or accpetance of such boundaries by MOST NEEDED ASSISTANCE (FIG. -

2018/2019 Annual School Census Report

Foreword Successful education policies are formed and supported by accurate, timely and reliable data, to improve governance practices, enhance accountability and ultimately improve the teaching and learning process in schools. Considering the importance of robust data collection, the Planning, Research and Statistics (PRS) Department, Katsina State Ministry of Education prepares and publishes the Annual Schools Census Statistical Report of both Public and Private Schools on an annual basis. This is in compliance with the National EMIS Policy and its implementation. The Annual Schools Census Statistical Report of 2018-2019 is the outcome of the exercise conducted between May and June 2019, through a rigorous activities that include training Head Teachers and Teachers on School Records Keeping; how to fill ASC questionnaire using school records; data collection, validation, entry, consistency checks and analysis. This publication is the 13th Annual Schools Census Statistical Report of all Schools in the State. In line with specific objectives of National Education Management Information System (NEMIS), this year’s ASC has obtained comprehensive and reliable data where by all data obtained were from the primary source (the school’s head provide all data required from schools records). Data on Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) of basic education and post basic to track the achievement of the State Education Sector Operational Plan (SESOP) as well as Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); feed data into the National databank to strengthen NEMIS for national and global reporting. The report comprises of educational data pertaining to all level both public and private schools ranging from pre-primary, primary, junior secondary and senior secondary level. -

Report on Epidemiological Mapping of Schistosomiasis and Soil Transmitted Helminthiasis in 19 States and the FCT, Nigeria

Report on Epidemiological Mapping of Schistosomiasis and Soil Transmitted Helminthiasis in 19 States and the FCT, Nigeria. May, 2015 Report on Epidemiological Mapping of Schistosomiasis and Soil Transmitted Helminthiasis in 19 States and the FCT, Nigeria. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................................... v LIST OF PLATES ...................................................................................................................................... vii FOREWORD .............................................................................................................................................. x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... xii 1.0 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Objectives of the Mapping Project ................................................................................................ 2 1.3 Justification for the Survey ............................................................................................................ 2 2.0. MAPPING METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................................. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

IOM Nigeria DTM Flash Report NCNW 23 August 2021

FLASH REPORT #66: POPULATION DISPLACEMENT DTM North West/North Central Nigeria Nigeria 16 - 22 AUGUST 2021 Aected Population: Damaged Shelters: Casualties: Movement Trigger: 3,161 Individuals 56 133 Armed attacks/Rainstorms OVERVIEW AFFECTED LOCATIONS Nigeria's North Central and North West Zones are afflicted with a mul�dimensional crisis that is rooted in long-standing tensions between ethnic and religious groups and involves a�acks by criminal groups and banditry/hirabah (such as kidnapping and grand larceny along major highways). The crisis has accelerated during the past NIGER REPUBLIC years because of the intensifica�on of a�acks and has resulted in widespread displacement across the region. Between 16 and 22 August 2021, armed clashes between herdsmen and farmers; and bandits and local communi�es as well as rainstorms have led to new waves of Sokoto popula�on displacement. Following these events, rapid assessments were conduct- ed by DTM (Displacement Tracking Matrix) field staff with the purpose of informing Batsari the humanitarian community and government partners, and enable targeted 1,617 14 response. Flash reports u�lise direct observa�on and a broad network of key infor- Kusada mants to gather representa�ve data and collect informa�on on the number, profile Katsina and immediate needs of affected popula�ons. Jigawa Zamfara Bukkuyum During the assessment period, the DTM iden�fied an es�mated number of 3,161 124 1,002 Kano individuals who were displaced to neigbouring wards. Of the total number of Faskari Kebbi Kiru displaced individuals, 2,864 persons were displaced because of communal clashes 198 Dandume in the LGAs Sabuwa, Dandume, Faskari and Batsari in Katsina State and Bukkuyum Sabuwa 19 LGA of Zamfara State. -

The State and Ecological Problems in Katsina, Nigeria

• A rican Arid Lands Working Paper Series ISSN 1102-4488 NORDISKA AfR\KAINSTITUiEi 1B 2 -02- , , UPPSA\.A Nordiska Afrikainstitutet (The Scandinavian Institute of African Studies) p O Box 1703, S-751 47 UPPSALA, Sweden Telex 8195077, Telefax 018-69 56 29 African Arid Lands Working Paper Series is published within the Nordiska Mrikainstitutet research prograrnrne Human Life in African Arid Lands, the main objectives of which are as follows: to encourage research in the drylands and the exchange of country and regional experiences, and to link up with the ongoing activities in Mrica and the Nordic countries to enhance the cooperation between social and natural science disciplines and indigenous knowledge to explore the hearing of developmental policies on the environment and the possibility of devising long-term strategies for the redemption of the fragile drylands environment Editorial staff: Anders Hjort af Ornäs, Director of Nordiska Afrikainstitutet M.A. Mohamed Salih, Prograrnrne Leader of Human Life in African Arid Lands Eva Lena Volk, Prograrnrne Assistant, Human Life in African Arid Lands illustration on front: Details from a decorated gourd (in Nigeria 's Traditional Crafts by Alison Hodge) A/riean Arid Lands Working Paper Series No. 1/92 THE STATE AND ECOLOGICAL PROBLEMS IN KATSINA, NIGERIA by A. M. SAULAWA Department of History, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, Nigeria. ABSTRACT An important feature in the Nigerian and African past and recent history has been the environment and its continuous inf1uence on the population. This issue is one that is much tied up with the ecological problems and the challenges they pose to the population. -

Prevalence of Trachoma in Katsina State, Nigeria: Results of 34 District-Level Surveys

Ophthalmic Epidemiology ISSN: 0928-6586 (Print) 1744-5086 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/iope20 Prevalence of Trachoma in Katsina State, Nigeria: Results of 34 District-Level Surveys Caleb Mpyet, Nasiru Muhammad, Mohammed Dantani Adamu, Habila Muazu, Murtala Mohammad Umar, Musa Goyol, Uwazoeke Onyebuchi, Ima Chima, Haliru Idris, Adamani William, Sunday Isiyaku, Benjamin Nwobi, Rebecca Mann Flueckiger, Rebecca Willis, Alexandre Pavluck, Brian K. Chu, Nicholas Olobio & Anthony W. Solomon To cite this article: Caleb Mpyet, Nasiru Muhammad, Mohammed Dantani Adamu, Habila Muazu, Murtala Mohammad Umar, Musa Goyol, Uwazoeke Onyebuchi, Ima Chima, Haliru Idris, Adamani William, Sunday Isiyaku, Benjamin Nwobi, Rebecca Mann Flueckiger, Rebecca Willis, Alexandre Pavluck, Brian K. Chu, Nicholas Olobio & Anthony W. Solomon (2016) Prevalence of Trachoma in Katsina State, Nigeria: Results of 34 District-Level Surveys, Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 23:sup1, 55-62, DOI: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1236975 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09286586.2016.1236975 Published with license by Taylor & Francis© Published online: 24 Oct 2016. 2016 Caleb Mpyet, Nasiru Muhammad, Mohammed Dantani Adamu, Habila Muazu, Murtala Mohammad Umar, Musa Goyol, Uwazoeke Onyebuchi, Ima Chima, Haliru Idris, Adamani William, Sunday Isiyaku, Benjamin Nwobi, Rebecca Mann Flueckiger, Rebecca Willis, Alexandre Pavluck, Brian K. Chu, Nicholas Olobio, and Anthony W. Solomon, for the Global Trachoma Mapping Project. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 303 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 3 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=iope20 OPHTHALMIC EPIDEMIOLOGY 2016, VOL. 23, NO. -

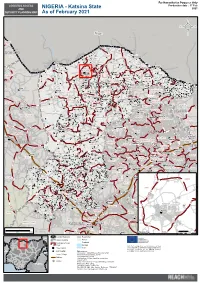

Katsina State 2021 SECURITY PLANNING MAP As of February 2021

For Humanitarian Purposes Only LOGISTICS ACCESS Production date : 17 Feb AND NIGERIA - Katsina State 2021 SECURITY PLANNING MAP As of February 2021 Niger SABON BIRNI Dutsin Bamli Forest* Dan Kunama Dan Kabba SOKOTO Forest Re Dagura Dadin Sarki ISA Matsai Maiaduwa KAITA Washemi Jibiya MAI'ADUA Jasai Kaita MASHI Mazanya Jerdedi Forest Zango Rese* Daura JIBIA Karawa Gulbin Baure KATSINA Forest* Zandam, Gulbi ZANGO Katsina Mashi Sandamu DAURA Forest Dan Tambara Fiwuni Kututure SHINKAFI Katsina Damakola Rese* Gurjiya Kigo, River Sandamu DUTSI Sukanawa MANI Unguwar GajeUnguwar Gaje Batagarawa Kaurin Saidu Pakarawa Forest* Maikiliya Dan Aunai SANDAMU Yantuba Dutsawa Lemo Tamdamwa Dutsawa Sabon Gari Fulani Giginya Nat* Forest Gidan Adamu Burudu Gargarawa Rese* Saboa Dandogo Rimi Mani Forest* Maibara Rimi Baure DancaleDancale Dutsi Kufani Adalawa Salei BATSARI Kawari Bardaya Zakata Dutsi BAURE Zurmi Gwiwa Kyaras ZURMI Yan Molo Batsari Alumu RIMI BINDAWA YANKWASHI Inga Dole GWIWA Musari Ungua Tsamia Tuwaru Sabuwa Dan KuliyaDan Gagi Daura Kuraye Yankwashi Kwahi Bagadi Safana Kabura Gawaji Kuma Faru Tachiawa Kurfi Yanuku Charanchi Roni Kazaure Ajiwa Bindawa Ingawa KURFI CHARANCHI Dandi Lake Gaiwa KAURA Dan Jakko Dambuna KAZAURE INGAWA Ruruma Birci NAMODA Kirkini Yakassa Jobe BABURA Gamda RONI Birni Mogaji Kankiya Gaci Kunchi MAKODA SAFANA Daddare Eaguwa Forest Rese JIGAWA Kusada BIRNIN MAGAJI Dutsin Ma KUSADA Dambatta Kafarda KUNCHI Safana KANKIA Makoda DAMBATTA GARKI Magwai, River Ungwan Adar Duru Ganuwa Dan-Tudu Makanwashi Karaduwa Jigawar Sawai