Mormonism and Maoism: the Church and People's China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'New Era' Should Have Ended US Debate on Beijing's Ambitions

Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on “A ‘China Model?’ Beijing’s Promotion of Alternative Global Norms and Standards” March 13, 2020 “How Xi Jinping’s ‘New Era’ Should Have Ended U.S. Debate on Beijing’s Ambitions” Daniel Tobin Faculty Member, China Studies, National Intelligence University and Senior Associate (Non-resident), Freeman Chair in China Studies, Center for Strategic and International Studies Senator Talent, Senator Goodwin, Honorable Commissioners, thank you for inviting me to testify on China’s promotion of alternative global norms and standards. I am grateful for the opportunity to submit the following statement for the record. Since I teach at National Intelligence University (NIU) which is part of the Department of Defense (DoD), I need to begin by making clear that all statements of fact and opinion below are wholly my own and do not represent the views of NIU, DoD, any of its components, or of the U.S. government. You have asked me to discuss whether China seeks an alternative global order, what that order would look like and aim to achieve, how Beijing sees its future role as differing from the role the United States enjoys today, and also to address the parts played respectively by the Party’s ideology and by its invocation of “Chinese culture” when talking about its ambitions to lead the reform of global governance.1 I want to approach these questions by dissecting the meaning of the “new era for socialism with Chinese characteristics” Xi Jinping proclaimed at the Communist Party of China’s 19th National Congress (afterwards “19th Party Congress”) in October 2017. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Question About Simon Leys/Pierre Ryckmans

H-Asia Question about Simon Leys/Pierre Ryckmans Discussion published by Nicholas Clifford on Friday, September 4, 2015 Sorry if this is going to the wrong place, but it's the sort of relatively simple question that it was possible to ask on H-ASIA in its earlier incarnation. Is this the appropriate place to put it? and if not, where should I try? Many thanks. I'm trying to find out exactly when "Simon Leys" was publically identified as "Pierre Ryckmans," at the time of his arguments with a powerful group of French academic Maoists. His Habits neufs du président Mao (The Chairman’s New Clothes) a chronicle of the Cultural Revolution, written in Hong Kong and based on the Chinese press and other sources) came out in France in 1971. Then, after a stay of six months in Beijing attached to the new Belgian embassy, he wrote Ombres chinoises (Chinese Shadows) which appeared in 1974. In 1975-76 he had a tussle with the French scholar Michelle Loi, whose primary interest lay in Lu Xun (whom Leys admired enormously, as he did George Orwell). In 1976 she published (in Switzerland) a brief pamphlet called Pour Luxun: réponse à Pierre Ryckmans (For Lu Xun: reply to Pierre Ryckmans) attacking him and his views on China and linking him to reactionary circles in American China studies, and those Americans who (she says) actually preferred Zhou Zuoren (Lu Xun’s collaborationist brother) to Lu Xun himself. She herself, though admitting the problems the CCP gave Lu Xun prior to his death in 1936, managed to put the blame not on Mao and the Maoists, but on Liu Shaoqi, Zhou Yang, and some of the others who were disgraced during the Cultural Revolution, and had not yet been rehabilitated at the time of her writing. -

Answer: Maoism Is a Form of Communism Developed by Mao Tse Tung

Ques 1: What is Maoism? Answer: Maoism is a form of communism developed by Mao Tse Tung. It is a doctrine to capture State power through a combination of armed insurgency, mass mobilization and strategic alliances. The Maoists also use propaganda and disinformation against State institutions as other components of their insurgency doctrine. Mao called this process, the ‘Protracted Peoples War’, where the emphasis is on ‘military line’ to capture power. Ques 2: What is the central theme of Maoist ideology? Answer: The central theme of Maoist ideology is the use of violence and armed insurrection as a means to capture State power. ‘Bearing of arms is non-negotiable’ as per the Maoist insurgency doctrine. The maoist ideology glorifies violence and the ‘Peoples Liberation Guerrilla Army’ (PLGA) cadres are trained specifically in the worst forms of violence to evoke terror among the population under their domination. However, they also use the subterfuge of mobilizing people over issues of purported inadequacies of the existing system, so that they can be indoctrinated to take recourse to violence as the only means of redressal. Ques 3: Who are the Indian Maoists? Answer: The largest and the most violent Maoist formation in India is the Communist Party of India (Maoist). The CPI (Maoist) is an amalgamation of many splinter groups, which culminated in the merger of two largest Maoist groups in 2004; the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist), People War and the Maoist Communist Centre of India. The CPI (Maoist) and all its front organizations formations have been included in the list of banned terrorist organizations under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967. -

INSTITUTE for POLICY REFORM Working Paper Series

339.5 • 1575 w-81 INSTITUTE • FOR POLICY REFORM • • • • WAITE MEMORIAL BOOK COLLECTION DEPT. OF AG. AND APPUED ECONOMICS 1994 BUFORD AVE. - 232 COB UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA ST. PAUL, MN 55108 U.S.A. • Working Paper Series The objective of the Institute enhance the foundation for broad based • for Policy Reform is to economic growth in developing countries. Through its research, education and training activities the Institute encourages active participation in the dialogue on policy reform, focusing on changes that stimulate and sustain economic development. At the core of these activities is the search for creative ideas that can be used to design constitutional, institutional and policy reforms. Research fellows and policy practitioners are engaged by IPR to expand • the analytical core of the reform process. This includes all elements of comprehensive and customized reforms packages, recognizing cultural, political, economic and environmental elements as crucial dimensions of societies. 1400 16th Street, NW / Suite 350 Washington, DC 20036 (202)3450 • 339.5 • 1575 w-81 INSTITUTE 0 FOR POLICY REFORM • IPR81 Federalism, Chinese Style: The Political Basis for Economic Success in China Barry Weingastl, Yingyi Qian2 and Gabriella Montinola3 * • WAITE MEMORIAL BOOK COLLECTION DEPT. OF AG. AND APPUED ECONOMICS 1994 BUFORD AVE. - 232 COB UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA ST. PAUL MN 56108 USA 0 Working Paper Series • The objective of the Institute for Policy Reform is to enhance the foundation for broad based economic growth in developing countries. Through its research, education and training activities the Institute encourages active participation in the dialogue on policy reform, focusing on changes that stimulate and sustain economic development. -

Mao Zedong in Contemporarychinese Official Discourse Andhistory

China Perspectives 2012/2 | 2012 Mao Today: A Political Icon for an Age of Prosperity Mao Zedong in ContemporaryChinese Official Discourse andHistory Arif Dirlik Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5852 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5852 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 4 June 2012 Number of pages: 17-27 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Arif Dirlik, « Mao Zedong in ContemporaryChinese Official Discourse andHistory », China Perspectives [Online], 2012/2 | 2012, Online since 30 June 2015, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5852 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5852 © All rights reserved Special feature China perspectives Mao Zedong in Contemporary Chinese Official Discourse and History ARIF DIRLIK (1) ABSTRACT: Rather than repudiate Mao’s legacy, the post-revolutionary regime in China has sought to recruit him in support of “reform and opening.” Beginning with Deng Xiaoping after 1978, official (2) historiography has drawn a distinction between Mao the Cultural Revolutionary and Mao the architect of “Chinese Marxism” – a Marxism that integrates theory with the circumstances of Chinese society. The essence of the latter is encapsulated in “Mao Zedong Thought,” which is viewed as an expression not just of Mao the individual but of the collective leadership of the Party. In most recent representations, “Chinese Marxism” is viewed as having developed in two phases: New Democracy, which brought the Communist Party to power in 1949, and “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” inaugurated under Deng Xiaoping and developed under his successors, and which represents a further development of Mao Zedong Thought. -

A Global Contest for Power and Influence

CHAPTER 1 U.S.-CHINA GLOBAL COMPETITION SECTION 1: A GLOBAL CONTEST FOR POWER AND INFLUENCE: CHINA’S VIEW OF STRA- TEGIC COMPETITION WITH THE UNITED STATES Key Findings • Beijing has long held the ambition to match the United States as the world’s most powerful and influential nation. Over the past 15 years, as its economic and technological prowess, dip- lomatic influence, and military capabilities have grown, China has turned its focus toward surpassing the United States. Chi- nese leaders have grown increasingly aggressive in their pur- suit of this goal following the 2008 global financial crisis and General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Xi Jinping’s ascent to power in 2012. • Chinese leaders regard the United States as China’s primary adversary and as the country most capable of preventing the CCP from achieving its goals. Over the nearly three decades of the post-Cold War era, Beijing has made concerted efforts to diminish the global strength and appeal of the United States. Chinese leaders have become increasingly active in seizing op- portunities to present the CCP’s one-party, authoritarian gover- nance system and values as an alternative model to U.S. global leadership. • China’s approach to competition with the United States is based on the CCP’s view of the United States as a dangerous ideologi- cal opponent that seeks to constrain its rise and undermine the legitimacy of its rule. In recent years, the CCP’s perception of the threat posed by Washington’s championing of liberal demo- cratic ideals has intensified as the Party has reemphasized the ideological basis for its rule. -

ACROSS the TAIWAN STRAIT: from COOPERATION to CONFRONTATION? 2013–2017

VOLUME 5 2014–2015 ACROSS THE TAIWAN STRAIT: from COOPERATION to CONFRONTATION? 2013–2017 Compendium of works from the China Leadership Monitor ALAN D. ROMBERG ACROSS THE TAIWAN STRAIT: from COOPERATION to CONFRONTATION? 2013–2017 Compendium of works from the China Leadership Monitor ALAN D. ROMBERG VOLUME FIVE July 28, 2014–July 14, 2015 JUNE 2018 Stimson cannot be held responsible for the content of any webpages belonging to other firms, organizations, or individuals that are referenced by hyperlinks. Such links are included in good faith to provide the user with additional information of potential interest. Stimson has no influence over their content, their correctness, their programming, or how frequently they are updated by their owners. Some hyperlinks might eventually become defunct. Copyright © 2018 Stimson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from Stimson. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1211 Connecticut Avenue Northwest, 8th floor Washington, DC 20036 Telephone: 202.223.5956 www.stimson.org Preface Brian Finlay and Ellen Laipson It is our privilege to present this collection of Alan Romberg’s analytical work on the cross-Strait relationship between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan. Alan joined Stimson in 2000 to lead the East Asia Program after a long and prestigious career in the Department of State, during which he was an instrumental player in the development of the United States’ policy in Asia, particularly relating to the PRC and Taiwan. He brought his expertise to bear on his work at Stimson, where he wrote the seminal book on U.S. -

"Thought Reform" in China| Political Education for Political Change

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1979 "Thought reform" in China| Political education for political change Mary Herak The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Herak, Mary, ""Thought reform" in China| Political education for political change" (1979). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1449. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1449 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUB SISTS, ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE: 19 7 9 "THOUGHT REFORM" IN CHINA: POLITICAL EDUCATION FOR POLITICAL CHANGE By Mary HeraJc B.A. University of Montana, 1972 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OP MONTANA 1979 Approved by: Graduat e **#cho o1 /- 7^ Date UMI Number: EP34293 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

The Construction and Characteristics of the Theoretical System of Xi Jinping’S View of History

Philosophy Study, August 2020, Vol. 10, No. 8, 503-510 doi: 10.17265/2159-5313/2020.08.004 D D AV I D PUBLISHING The Construction and Characteristics of the Theoretical System of Xi Jinping’s View of History YU Guirong Northeastern University, Shenyang, China Xi’s historical view is a scientific theoretical system with a tight logical structure. The construction of this theoretical system follows the principles and methods of the construction of Marxist theoretical system. The theoretical features of Xi’s view of history are unity of theory and practice, unity of politics and science, unity of universality and nationality, unity of collective wisdom and individual wisdom, unity of dialectical thinking and historical thinking, and unity of history, reality, and future. Keywords: Xi Jinping, view of history, construction, logical system Xi Jinping’s view of history is the significant inheritance and development of Marxist theory of history by the central leading collective of the Party with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core in the new era, and it is the Party’s fundamental viewpoint and view on history and its development as well as the basic principle and methodology for the Party to observe and study historical phenomena and problems. In the new era, to study Xi Jinping’s view of history, it is necessary to make an in-depth study and scientific exposition of the construction and characteristics of its theoretical system. The Construction of the Theoretical System of Xi’s View of History There is no doubt that the contents of Xi’s view of history are mainly put forward by Xi Jinping, with its theoretical content existing in its concrete theoretical form or text form as a natural form. -

SWEDISH MAOISM After the People's Republic of China Was

CHAPTER EIGHT SWEDISH MAOISM It was people such as these who helped create an image of the human face of China (Colin Mackerras on Jan Myrdal and Sven Lindqvist 1991, 186). After the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, West- erners were driven out of the country. The new leaders considered the Westerners to be imperialists, and the Chinese state took first their property and then businesses away from them.1 Many had already left because of the Japanese occupation and, apart from a small contingent of Communist sympathizers, those remaining were now forced out. This also spelled the end for the adventurous Western geological expe- ditions and collecting trips. But in Sweden, interest in China survived this setback and rebounded even stronger in the 1970s. The focus of that decade, however, had little to do on the surface with the study of ancient China that had occupied Bernhard Karlgren and Johan Gunnar Andersson. The new Swedish China fever was all about the future. The promise of a New China that would change the world per- meated the Asianist community, and the Swedes were there to glorify the coming utopia. During the sixties and seventies, young Swedes were engaged actively in the ideology of Maoism while they fervently praised the Chinese style of Communism.2 The Swedish media at the same time moved to the left. High-ranking editors wrote lyrical opinions about China’s Cultural Revolution that appeared in Dagens Nyheter, Sweden’s lead- ing daily. When state monopolized television started a second channel in 1968, many staff members were from the radical left.3 The Maoist 1 Sections from the following pages are included in a chapter in The Cold War in Asia: The Battle for Hearts and Minds, edited by Zheng Yangwen, Hong Liu and Michael Szonyi, published by Brill. -

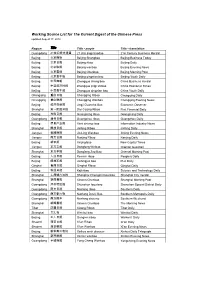

Working Source List for the Current Digest of the Chinese Press Updated August 17, 2012

Working Source List for The Current Digest of the Chinese Press updated August 17, 2012 Region Title Title - pinyin Title - translation Guangdong 21世纪经济报道 21 shiji jingji baodao 21st Century Business Herald Beijing 北京商报 Beijing Shangbao Beijing Business Today Beijing 北京日报 Beijing ribao Beijing Daily Beijing 北京晚报 Beijing wanbao Beijing Evening News Beijing 北京晨报 Beijing Chenbao Beijing Morning Post Beijing 北京青年报 Beijing qingnian bao Beijing Youth Daily Beijing 中国商報 Zhongguo shang bao China Business Herald Beijing 中国经济时报 Zhongguo jingji shibao China Economic Times Beijing 中国青年报 Zhongguo qingnian bao China Youth Daily Chongqing 重庆日报 Chongqing Ribao Chongqing Daily Chongqing 重庆晚报 Chongqing Wanbao Chongqing Evening News Beijing 经济观察报 Jingji Guancha Bao Economic Observer Shanghai 第一财经日报 Diyi Caijing Ribao First Financial Daily Beijing 光明日报 Guangming ribao Guangming Daily Guangdong 廣州日報 Guangzhou ribao Guangzhou Daily Beijing 信息产业报 Xinxi chanye bao Information Industry News Shanghai 解放日报 Jiefang Ribao Jiefang Daily Jiangsu 金陵晚报 Jin Ling Wanbao Jinling Evening News Jiangsu 南京日报 Nanjing Ribao Nanjing Daily Beijing 新京报 Xinjing bao New Capital Times Jiangsu 东方卫报 Dongfang Weibao Oriental Guardian Shanghai 东方早报 Dongfang Zao Bao Oriental Morning Post Beijing 人民日报 Renmin ribao People's Daily Beijing 解放军报 Jiefangjun bao PLA Daily Qinghai 青海日报 Qinghai Ribao Qinghai Daily Beijing 科技日报 Keji ribao Science and Technology Daily Shanghai 上海城市导报 Shanghai Chengshi Dao Bao Shanghai City Herald Shanghai 新闻晨报 Xinwen Chenbao Shanghai Morning Post Guangdong 深圳特区报 Shenzhen