The Karelia Cross-Border Cooperation Programme A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ST61 Publication

Section spéciale Index BR IFIC Nº 2477 Special Section ST61/ 1479 Sección especial Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Date/Fecha : 03.09.2002 Date limite pour les commentaires pour Partie A / Expiry date for comments for Part A / fecha limite para comentarios para Parte A : 26.11.2002 Description of Columns / Descripción de columnas / Description des colonnes Intent Purpose of the notification Propósito de la notificación Objet de la notification 1a Assigned frequency Frecuencia asignada Fréquence assignée 4a Name of the location of Tx station Nombre del emplazamiento de estación Tx Nom de l'emplacement de la station Tx 4b Geographical area Zona geográfica Zone géographique 4c Geographical coordinates Coordenadas geográficas Coordonnées géographiques 6a Class of station Clase de estación Classe de station 1b Vision / sound frequency Frecuencia de portadora imagen/sonido Fréquence image / son 1ea Frequency stability Estabilidad de frecuencia Stabilité de fréquence 1e carrier frequency offset Desplazamiento de la portadora Décalage de la porteuse 7c System and colour system Sistema de transmisión / color Système et système de couleur 9d Polarization Polarización Polarisation 13c Remarks Observaciones Remarques 9 Directivity Directividad Directivité -

The Case of Karelia Stepanova, S

www.ssoar.info Tourism development in border areas: a benefit or a burden? The case of Karelia Stepanova, S. V. Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Stepanova, S. V. (2019). Tourism development in border areas: a benefit or a burden? The case of Karelia. Baltic Region, 11(2), 94-111. https://doi.org/10.5922/2079-8555-2019-2-6 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-64250-8 Tourism TOURISM DEVELOPMENT Border regions are expected to IN BORDER AREAS: benefit from their position when it comes to tourism development. In A BENEFIT OR A BURDEN? this article, I propose a new ap- THE CASE OF KARELIA proach to interpreting the connec- tion between an area’s proximity to 1 S. V. Stepanova the national border and the devel- opment of tourism at the municipal level. The aim of this study is to identify the strengths and limita- tions of borderlands as regards the development of tourism in seven municipalities of Karelia. I examine summarised data available from online and other resources, as well as my own observations. Using me- dian values, I rely on the method of content analysis of strategic docu- ments on the development of cross- border municipalities of Karelia. -

Newsletter Sept15

Swedish -Karelian Business and Information Center SKBIC NEWSLETTER September 2015 Coming up: • 8th International Bar- ents Region Habitat Forum of municipalities: Karelia - Contact Forum. Petrozavodsk, Sep- Västerbotten tember 28—October 2, 2015. Arranging match-making forums for the twinning municipalities has become a good tradition in Karelia - Västerbotten cooperation. The previous conference took place in • III International Fo- 2011, now after four years partners would like to gather again and meet new people, rum for Energy Effi- learn about latest developments and simply collect personal opinions and experi- ciency, Environment ences. The forum to take place in Petrozavodsk on November 12-13. Swedish mu- and Communal Infra- nicipalities of Umeå, Malå, Vindeln, Lycksele and Robertsfors are invitied to meet structure. Petro- zavodsk, October 28 their counterparts from Petrozavodsk, Medvezhyegorsk, Pryazha, Olonets and Kosto- -30. muksha. Energy Efficiency at Hospitals - the project is continued SKBIC continues implementation of the project "Energy Efficiency at hospitals". In January 2015 expert from Umeå Kjell Blombäck, representing the Swedish company Ramboll, met with officials of Karelian Health Care Ministry and work- ers of Children's Republican Hospital to discuss a set of specific technical meas- ures aimed at reducing electricity, hot water consumption and heat losses in the hospital building. In June 2015 Mr. Blombäck returned to present to the Ministry the technical so- lutions, allowing to reduce energy con- sumption and heat loss in the building of the Children's Republican Hospital. The draft plan was discussed and to be finalized in autumn 2015. Discus sing the plan of upcoming activities at SKBIC office Green Economy project finalized Supported by the Nordic Council of Ministers “Green Economy” project was initially planned for implemen- tation until autumn 2015. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

Trends in Molecular Epidemiology of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis In

Mokrousov et al. BMC Microbiology (2015) 15:279 DOI 10.1186/s12866-015-0613-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Trends in molecular epidemiology of drug-resistant tuberculosis in Republic of Karelia, Russian Federation Igor Mokrousov1*, Anna Vyazovaya1, Natalia Solovieva2, Tatiana Sunchalina3, Yuri Markelov4, Ekaterina Chernyaeva5,2, Natalia Melnikova2, Marine Dogonadze2, Daria Starkova1, Neliya Vasilieva2, Alena Gerasimova1, Yulia Kononenko3, Viacheslav Zhuravlev2 and Olga Narvskaya1,2 Abstract Background: Russian Republic of Karelia is located at the Russian-Finnish border. It contains most of the historical Karelia land inhabited with autochthonous Karels and more recently migrated Russians. Although tuberculosis (TB) incidence in Karelia is decreasing, it remains high (45.8/100 000 in 2014) with the rate of multi-drug resistance (MDR) among newly diagnosed TB patients reaching 46.5 %. The study aimed to genetically characterize Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates obtained at different time points from TB patients from Karelia to gain insight into the phylogeographic specificity of the circulating genotypes and to assess trends in evolution of drug resistant subpopulations. Methods: The sample included 150 M. tuberculosis isolates: 78 isolated in 2013–2014 (“new” collection) and 72 isolated in 2006 (“old” collection). Drug susceptibility testing was done by the method of absolute concentrations. DNA was subjected to spoligotyping and analysis of genotype-specific markers of the Latin-American-Mediterranean (LAM) family and its sublineages and Beijing B0/W148-cluster. Results: The largest spoligotypes were SIT1 (Beijing family, n = 42) and SIT40 (T family, n = 5). Beijing family was the largest (n = 43) followed by T (n =11),Ural(n =10)andLAM(n = 8). -

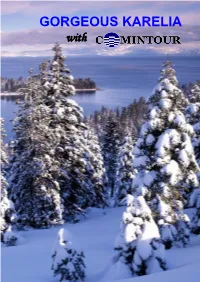

GORGEOUS KARELIA With

GORGEOUS KARELIA with 1 The tours presented in this brochure aim to country had been for centuries populated by the introduce customers to the unique beauty and Russian speaking Pomors – proud independent folk culture of the area stretching between the southern that were at the frontier of the survival of the settled coast of the White Sea and the Ladoga Lake. civilization against the harshness of the nature and Karelia is an ancient land that received her name paid allegiance only to God and their ancestors. from Karelians – Finno-Ugric people that settled in that area since prehistoric times. Throughout the For its sheer territory size (half of that of Germany) history the area was disputed between the Novgorod Karelia is quite sparsely populated, making it in fact Republic (later incorporated into Russian Empire) the biggest natural reserve in Europe. The and Kingdom of Sweden. In spite of being Orthodox environment of this part of Russia is very green and Christians the Karelians preserved unique feel of lavish in the summer and rather stern in the winter, Finno-Ugric culture, somehow similar to their but even in the cold time of the year it has its own Finnish cousins across the border. East of the unique kind of beauty. Fresh water lakes and rivers numbered in tens of thousands interlace with the dense taiga pine forest and rocky outcrops. Wherever you are in Karelia you never too far from a river or lake. Large deposits of granite and other building stones give the shores of Karelian lakes a uniquely romantic appearance. -

Media Audiences in a Russian Province

Media Audiences in a Russian Province JUKKA PIETILÄINEN During the last 15 years of the 20th century, Rus- The aim of this article is to illuminate the press sian society and media experienced a major change competition in Karelia and to find out which factors from a centrally planned, authoritarian and unified have an impact on newspaper choice. The data is Soviet society to a market-based, (at least partly) based on two surveys collected in the Republic of democratic and fragmented society. With the col- Karelia, the first one in February 2000 in Petroza- lapse of the Soviet system, the former press struc- vodsk and the second one in January-February ture with dominant national newspapers collapsed 2002 in Petrozavodsk, Kondopoga and Pryazha and regional newspapers became the most impor- (Prääsä).1 tant part of the press. At the same time, newspaper publishing shifted from a daily (usually six times a The Media in Petrozavodsk week) to a weekly rhythm, so that in 2000 the cir- culation of weeklies was almost two thirds of the and Karelia circulation of all newspapers (excluding newspapers Petrozavodsk is the capital of the Republic of published irregularly or less than once a week) (for Karelia, one of the ethnic republics of the Russian these statistics see Pietiläinen 2002a, 124-125 and Federation. It has 280,000 inhabitants, of which Pietiläinen 2002b, 213-217). According to many 81% are ethnic Russian, 5% Karelian and 3% Finn- studies (Wyman 1997, 108; Resnyanskaya & Fomi- ish. Petrozavodsk is a small regional centre in cheva 1999, 87-88), newspapers have also been los- Northern Russia. -

Hot Spots Report

Assessment of Describing the state of the Barents 42 original Barents Hot Spot Report environmental ‘hot spots’ AZAROVA N NA NA I IR Assessment of the Barents Environmental Hot Spots Report Assessment of the Barents Hot Spot Report describing the state of 42 original Barents environmental "hot spots". Part I – Analysis. Akvaplan-niva Report. NEFCO/BHSF, 2013. 119 p. Authors: Alexei Bambulyak, Akvaplan-niva, Norway Svetlana Golubeva, System Development Agency, Russia Vladimir Savinov, Akvaplan-niva, Norway Front page figure: map with the Barents environmental "hot spots". Source: barentsinfo.fi The assessment was carried out and the report produced on behalf of NEFCO/BHSF. 2 Assessment of the Barents Environmental Hot Spots Report Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................5 1. Summary .............................................................................................................................6 2. Introduction .........................................................................................................................9 3. The Barents environmental hot spot process ..................................................................... 11 3.1 The first NEFCO/AMAP report of 1995. Initiative, goals and outcome ................................. 13 3.2 The second NEFCO/AMAP report of 2003 on Updating the Environmental "Hot Spot" List. Goals and outcome – 42 "hot spots" ................................................................................. -

Media Audiences in a Russian Province

10.1515/nor-2017-0300 Media Audiences in a Russian Province JUKKA PIETILÄINEN During the last 15 years of the 20th century, Rus- The aim of this article is to illuminate the press sian society and media experienced a major change competition in Karelia and to find out which factors from a centrally planned, authoritarian and unified have an impact on newspaper choice. The data is Soviet society to a market-based, (at least partly) based on two surveys collected in the Republic of democratic and fragmented society. With the col- Karelia, the first one in February 2000 in Petroza- lapse of the Soviet system, the former press struc- vodsk and the second one in January-February ture with dominant national newspapers collapsed 2002 in Petrozavodsk, Kondopoga and Pryazha and regional newspapers became the most impor- (Prääsä).1 tant part of the press. At the same time, newspaper publishing shifted from a daily (usually six times a The Media in Petrozavodsk week) to a weekly rhythm, so that in 2000 the cir- culation of weeklies was almost two thirds of the and Karelia circulation of all newspapers (excluding newspapers Petrozavodsk is the capital of the Republic of published irregularly or less than once a week) (for Karelia, one of the ethnic republics of the Russian these statistics see Pietiläinen 2002a, 124-125 and Federation. It has 280,000 inhabitants, of which Pietiläinen 2002b, 213-217). According to many 81% are ethnic Russian, 5% Karelian and 3% Finn- studies (Wyman 1997, 108; Resnyanskaya & Fomi- ish. Petrozavodsk is a small regional centre in cheva 1999, 87-88), newspapers have also been los- Northern Russia. -

Karelia a Perfect Fit for Your Investment

KARELIA A PERFECT FIT FOR YOUR INVESTMENT 2019 KARELIAINVEST.RU INVEST IN RUSSIA CONTENT Infrastructure for business. Development indicators ............................. 4 Key industries: Forestry .......................................................................................................... 24 Fishery ........................................................................................................... 28 Mining ............................................................................................................ 34 Tourism and recreation ............................................................................... 38 Success stories. Foreign investors in Karelia .......................................... 44 Support of investment activities ................................................................ 54 INFRASTRUCTURE FOR BUSINESS. I DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION Murmansk region SWEDEN Kostomuksha Stockholm 1300 km FINLAND Republic Kem of Karelia Belomorsk Segezha The Baltic Sea Helsinki 740 km Sortavala Kondopoga Tallinn 800 km Petrozavodsk Saint-Petersburg 412 km Riga ESTONIA 990 km Leningrad region LITHANIA LATVIA Vologda region Pskov Novgorod 710 km 510 km Vologda Vilnius Novgorod km 990 km 930 region Pskov Tver region Yaroslavl region region BELARUS Yaroslavl Moscow Tver 1100 kmкм km Minsk 1000 850 km 1300 km OVER 45 MLN. PEOPLE INFRASTRUCTURE FOR BUSINESS live within a 1000 km radius from Petrozavodsk • total area: 180,5 thousand square kilometers; • population: 618,1 thousand people; • -

The Regional Newspaper in Post-Soviet Russia

JUKKA PIETILÄINEN THE REGIONAL NEWSPAPER IN POST-SOVIET RUSSIA Society, Press and Journalism in the Republic of Karelia 1985-2001 ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Science of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the Paavo Koli Auditorium of the Pinni Building, Kanslerinrinne 1, Tampere on October 5th, 2002 at 12 oclock' University of Tampere Tampere 2002 Jukka Pietiläinen THE REGIONAL NEWSPAPER IN POST-SOVIET RUSSIA Society, Press and Journalism in the Republic of Karelia 1985-2001 Media Studies 1 Academic Dissertation University of Tampere, Department of Journalism and Mass Communication FINLAND Copyright © Tampere University Press Sales Bookshop TAJU P.O. BOX 617, 33014 University of Tampere Finland Tel. +358 3 215 6055 Fax +358 3 215 7685 email [email protected] http://granum.uta.fi Cover design: Mikko Keinonen Page design: Aila Helin Printed dissertation ISBN 951-44-5454-5 Electronic dissertation Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 209 ISBN 951-44-5463-4 ISSN 1456-954X http://acta.uta.fi Tampereen Yliopistopaino Oy Tampere 2002 2 Contents Preface ............................................................................................ 7 Acknowledgements ........................................................................ 9 1. Introduction.............................................................................13 1.1. Challenge of Russia .................................................................... 13 1.2. Research object.......................................................................... -

RUSSIAN KARELIA from Archangel to St Petersburg 24 May to 7 June 2017 Russian Karelia

RUSSIAN KARELIA from Archangel to St Petersburg 24 May to 7 June 2017 Russian Karelia The history of this area which reaches up to the White Sea is intertwined with that of Finland, sharing a landscape, a mythical heritage and a language. It became part of Russia after WWII. The area has attracted monastic communities and builders of wooden churches. The petroglyphs indicate that the area has been occupied for a very long time, and there are enigmatic labyrinths which hint at something mysterious. Our journey takes us from the port of Archangel, where it sits on the banks of the Northern Dvina River, to the remarkable Solovetsky Islands. Their history describes in miniature some of the tribulations of the last century. Happily the monastic com- munity has returned and the islands have become once again a remarkable retreat. One of the notable features of this area is the use of wood for architecture. We plan to see some remarkable wooden churches at a number of places including at Kondopogo, and on Kizhi Island at the north- ern end of Onego Lake. We will also visit the monastery on Valaam Island on Lake Ladoga. Trav- elling at this time of year ensures that we experience ‘The White Nights’ of 24 hour daylight! The tour will use trains, boats and planes as well as minibuses to travel around, before we spend our last few days seeing something of the magnificent glories of St Petersburg. HIGHLIGHTS Archangel Open-air Museum of Wooden Architecture, Malye Korely The Solovetsky Islands, in the White Sea The wooden church at Kondopoga Petrozavodsk, capital of Russian Karelia Zizhi Island, Onego Lake Valaam Island, Ladago Lake St Petersburg Led by Rufus Reade JOURNEY DETAILS The Itinerary Location: Northwestern 24 May Your Russia flight flight to St Peters- Dates: 24 May to 7 June burg for an overnight.