Guide to Recording Wildlife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survey of Fungi at the University of Wisconsin-Waukesha Field Station

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Field Station Bulletins UWM Field Station Spring 1993 A survey of fungi at the University of Wisconsin- Waukesha Field Station Alan D. Parker University of Wisconsin-Waukesha Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/fieldstation_bulletins Part of the Forest Biology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Parker, A.D. 1993 A survey of fungi at the University of Wisconsin-Waukesha Field Station. Field Station Bulletin 26(1): 1-10. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Field Station Bulletins by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Survey of Fungi at the University of Wisconsin-Waukesha Field Station Alan D. Parker Department of Biological Sciences University of Wisconsin-Waukesha Waukesha, Wisconsin 53188 Introduction The University of Wisconsin-Waukesha Field Station was founded in 1967 through the generous gift of a 98 acre farm by Ms. Gertrude Sherman. The facility is located approximately nine miles west of Waukesha on Highway 18, just south of the Waterville Road intersection. The site consists of rolling glacial deposits covered with old field vegetation, 20 acres of xeric oak woods, a small lake with marshlands and bog, and a cold water stream. Other communities are being estab- lished as a result of restoration work; among these are mesic prairie, oak opening, and stands of various conifers. A long-term study of higher fungi and Myxomycetes, primarily from the xeric oak woods, was started in 1978. -

SMR Lettre D'informations N° 2017-05

1 Lettre d'informations n° 21 – 2017/05 Rencontres mycologiques 2017 Catherine PAYANT La Société Mycologique de Rennes organise cette année les rencontres mycologiques inter associatives. Elles se tiendront le dimanche 14 mai à partir de 9h30 à Néant-sur-Yvel et regrouperont l’Association Mycologique Ploemeur Morbihan (AMPM), le Groupe Mycologique Nazairien (GMN) et bien sûr la SMR. Le RV est au parking de Folle Pensée (Fontaine de Barenton), commune de Paimpont à 10h . De là, balade pédestre accompagnée et commentée sur les chemins enchantés de la Forêt mythique de Paimpont sous la conduite de guides. Vers 12h départ des voitures en cortège pour Tlohan près de Néant sur Yvel, à environ 7 km de la Fontaine de Barenton. Pique-nique près d'un étang, précédé d'un apéritif offert par la SMR. Pensez à apporter vos tables et chaises. En cas de mauvais temps, sur ce lieu un vaste abri couvert est à notre disposition mais les dieux de la forêt seront avec nous ! L'après-midi peut être libre ou balade vers l'Arbre d'or et, ou visite de la très jolie église de Tréhorenteuc. 22 avril 2017 : dans les dunes Plouharnel (56) Dimitri BACRO Plusieurs membres de l’association mycologique de Ploemeur Morbihan sont venus nous rendre une petite visite à l’heure du pique-nique. Nous avons pu consulter un petit inventaire des champignons récoltés dans les dunes. Parmi les espèces couramment rencontrées, une morille plutôt méridionale, Morchella dunensis . Et en dépit des conditions climatiques proches de la sécheresse, nous en avons trouvé trois ou quatre, dont la première, énorme, avait séché sur pied à l’entrée d’un terrier de lapin ! (S’il est vrai que l’urine des diabétiques favorise l’apparition des morilles, voilà qui nous interroge sur celle des lapins. -

El Género Morchella Dill. Ex Pers. En Illes Balears

20210123-20210128 El género Morchella Dill. ex Pers. en Illes Balears (1) JAVIER MARCOS MARTÍNEZ C/Alfonso IX, 30, Bajo derecha. 37500. Ciudad Rodrigo, Salamanca, España. Email: [email protected] (2) GUILLEM MIR Solleric, 76. E-07340 Alaró, Mallorca, Illes Balears, España. E-mail: [email protected] (3) GUILHERMINA MARQUES CITAB, Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Departamento de Agronomía, 5001-801. Vila Real, Portugal. Email: [email protected] Resumen: MARCOS, J.; MIR, G. & G. MARQUES (2021). El género Morchella Dill. ex Pers. en Illes Balears. Se realiza una revisión de las especies del género Morchella recolectadas hasta la fecha en las Illes Balears, aportando nuevas citas, fotografías, descripciones macroscópicas y microscópicas, ecología y distribución de las especies. Además, para confirmar la identidad de las especies, se identificaron algunas muestras mediante análisis molecular. Destacan dos especies que son nuevas para el catálogo micológico de las Islas: M. galilaea Masaphy & Clowez y M. rufobrunnea Guzman & F. Tapia y dos nuevas para el catálogo de la isla de Mallorca: M. dunalii Boud. y M. dunensis (Castañera, J.L. Alonso & G. Moreno) Clowez. Palabras clave: Ascomycotina, Morchella, Islas Baleares, España. Abstract: MARCOS, J.; MIR, G. & G. MARQUES (2021). The genus Morchella Dill. ex Pers. in Balearic Island. The species of the genus Morchella collected to date in the Balearic Islands are reviewed, providing new appointments, photographies, macroscopics and microscopic descriptions, ecology and distributions of the species. Additionally in order to confirm the identity of the species some samples were identified by molecular analysis. Two species are new appointments for mycologic catalogue of the Islands: M. -

ZOOLOGY Zoology 110 (2007) 409–429

ARTICLE IN PRESS ZOOLOGY Zoology 110 (2007) 409–429 www.elsevier.de/zool Towards an 18S phylogeny of hexapods: Accounting for group-specific character covariance in optimized mixed nucleotide/doublet models Bernhard Misofa,Ã, Oliver Niehuisa, Inge Bischoffa, Andreas Rickerta, Dirk Erpenbeckb, Arnold Staniczekc aAbteilung fu¨r Entomologie, Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, D-53113 Bonn, Germany bDepartment of Coelenterata and Porifera (Zoologisch Museum), Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, University of Amsterdam, P.O. Box 94766, 1090 GT Amsterdam, The Netherlands cStaatliches Museum fu¨r Naturkunde Stuttgart, Abt. Entomologie, Rosenstein 1, D-70191 Stuttgart, Germany Received 19 May 2007; received in revised form 2 August 2007; accepted 22 August 2007 Abstract The phylogenetic diversification of Hexapoda is still not fully understood. Morphological and molecular analyses have resulted in partly contradicting hypotheses. In molecular analyses, 18S sequences are the most frequently employed, but it appears that 18S sequences do not contain enough phylogenetic signals to resolve basal relationships of hexapod lineages. Until recently, character interdependence in these data has never been treated seriously, though possibly accounting for the occurrence of biased results. However, software packages are readily available which can incorporate information on character interdependence within a Bayesian approach. Accounting for character covariation derived from a hexapod consensus secondary structure model and applying mixed DNA/RNA substitution models, our Bayesian analysis of 321 hexapod sequences yielded a partly robust tree that depicts many hexapod relationships congruent with morphological considerations. It appears that the application of mixed DNA/RNA models removes many of the anomalies seen in previous studies. We focus on basal hexapod relationships for which unambiguous results are missing. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

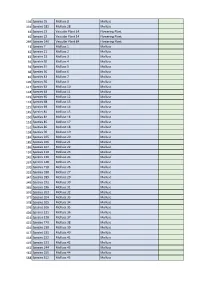

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Biodiversity Climate Change Impacts Report Card Technical Paper 12. the Impact of Climate Change on Biological Phenology In

Sparks Pheno logy Biodiversity Report Card paper 12 2015 Biodiversity Climate Change impacts report card technical paper 12. The impact of climate change on biological phenology in the UK Tim Sparks1 & Humphrey Crick2 1 Faculty of Engineering and Computing, Coventry University, Priory Street, Coventry, CV1 5FB 2 Natural England, Eastbrook, Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge, CB2 8DR Email: [email protected]; [email protected] 1 Sparks Pheno logy Biodiversity Report Card paper 12 2015 Executive summary Phenology can be described as the study of the timing of recurring natural events. The UK has a long history of phenological recording, particularly of first and last dates, but systematic national recording schemes are able to provide information on the distributions of events. The majority of data concern spring phenology, autumn phenology is relatively under-recorded. The UK is not usually water-limited in spring and therefore the major driver of the timing of life cycles (phenology) in the UK is temperature [H]. Phenological responses to temperature vary between species [H] but climate change remains the major driver of changed phenology [M]. For some species, other factors may also be important, such as soil biota, nutrients and daylength [M]. Wherever data is collected the majority of evidence suggests that spring events have advanced [H]. Thus, data show advances in the timing of bird spring migration [H], short distance migrants responding more than long-distance migrants [H], of egg laying in birds [H], in the flowering and leafing of plants[H] (although annual species may be more responsive than perennial species [L]), in the emergence dates of various invertebrates (butterflies [H], moths [M], aphids [H], dragonflies [M], hoverflies [L], carabid beetles [M]), in the migration [M] and breeding [M] of amphibians, in the fruiting of spring fungi [M], in freshwater fish migration [L] and spawning [L], in freshwater plankton [M], in the breeding activity among ruminant mammals [L] and the questing behaviour of ticks [L]. -

Diptera: Syrphidae)

Eur. J. Entomol. 102: 539–545, 2005 ISSN 1210-5759 Landscape parameters explain the distribution and abundance of Episyrphus balteatus (Diptera: Syrphidae) JEAN-PIERRE SARTHOU1, ANNIE OUIN1, FLORENT ARRIGNON1, GAËL BARREAU2 and BERNARD BOUYJOU1 1Ecole Nationale Supérieure Agronomique de Toulouse, UMR Dynafor, BP 107, F-31326 Auzeville-Tolosane, France; e-mail: [email protected] 212, rue Claude Bizot, F-33170 Gradignan, France Key words. Syrphidae, Episyrphus balteatus, distribution, abundance, seasons, forest edges, landscape Abstract. We studied the importance of forest structure (shape, edge length and orientation) and the crop mosaic (percentage of crops in the total land cover, within 100 and 2000 m from the forests) to the dynamics of an aphidophagous hoverfly Episyrphus bal- teatus. Adults were collected by Malaise traps located within and on the south- and north-facing edges of 54 forests. In winter, E. balteatus was only found on south-facing edges because of the greater insolation and temperature. In summer, it was more abundant on north-facing edges because of the abundant presence of flowers. In spring, more adults were found on long and south-facing edges than on northern edges. The presence of shrubs within 2000 m also positively affected abundance. In autumn, abundance was positively associated with length of the north-facing edge and forest shape. Emergence traps revealed that in southern France, E. bal- teatus may overwinter in the larval or puparial stage in forest edges. Overwintering was earlier reported only in adults. Landscape structure, length of forest edges and probably presence of shrub fallows, influence abundance of Episyrphus balteatus. INTRODUCTION farmed landscape are area, floristic composition and also Because most of the natural enemies of crop pests do the shape of the largest features (Nentwig, 1988; not carry out their complete life cycle in cultivated fields, Molthan, 1990; Thomas et al., 1992). -

FIT Count Insect Guide

Flower-Insect Timed Count: insect groups identification guide This guide has been developed to support the Flower-Insect Timed Count survey (FIT Count) that forms part of the UK Pollinator Monitoring Scheme (PoMS). Who is organising this project? The FIT Count is part of the Pollinator Monitoring Scheme (PoMS) within the UK Pollinator Monitoring and Research Partnership, co-ordinated by the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (CEH). It is jointly funded by Defra, the Welsh and Scottish Governments, JNCC and project partners, including CEH, the Bumblebee Conservation Trust, Butterfly Conservation, British Trust for Ornithology, Hymettus, the University of Reading and University of Leeds. PoMS aims to provide much-needed data on the state of the UK’s insect pollinators, especially wild bees and hoverflies, and the role they fulfil in supporting farming and wildlife. For further information about PoMS go to: www.ceh.ac.uk/pollinator-monitoring Defra project BE0125/ NEC06214: Establishing a UK Pollinator Monitoring and Research Partnership This document should be cited as: UK Pollinator Monitoring Scheme. 2019. Flower-Insect Timed Count: insect groups identification guide. Version 4. CEH Wallingford. Bee or wasp (Hymenoptera)? – 1 Honey Bee (family Apidae, species Apis mellifera) A social wasp (family Vespidae, genus Vespula) Photo © Bob Peterson/Wikimedia Commons Photo © Trounce/Wikimedia Commons most bees are more hairy than wasps at rest, wings are rolled up for some wasps (not all) Pollinator Monitoring Scheme: FIT Count FIT Scheme: Monitoring -

A Four-Locus Phylogeny of Rib-Stiped Cupulate Species Of

A peer-reviewed open-access journal MycoKeys 60: 45–67 (2019) A four-locus phylogeny of of Helvella 45 doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.60.38186 RESEARCH ARTICLE MycoKeys http://mycokeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A four-locus phylogeny of rib-stiped cupulate species of Helvella (Helvellaceae, Pezizales) with discovery of three new species Xin-Cun Wang1, Tie-Zhi Liu2, Shuang-Lin Chen3, Yi Li4, Wen-Ying Zhuang1 1 State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China 2 College of Life Sciences, Chifeng University, Chifeng, Inner Mongolia 024000, China 3 College of Life Sciences, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, Jiangsu 210023, China 4 College of Food Science and Engineering, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, Jiangsu 225127, China Corresponding author: Wen-Ying Zhuang ([email protected]) Academic editor: T. Lumbsch | Received 11 July 2019 | Accepted 18 September 2019 | Published 31 October 2019 Citation: Wang X-C, Liu T-Z, Chen S-L, Li Y, Zhuang W-Y (2019) A four-locus phylogeny of rib-stiped cupulate species of Helvella (Helvellaceae, Pezizales) with discovery of three new species. MycoKeys 60: 45–67. https://doi. org/10.3897/mycokeys.60.38186 Abstract Helvella species are ascomycetous macrofungi with saddle-shaped or cupulate apothecia. They are distri- buted worldwide and play an important ecological role as ectomycorrhizal symbionts. A recent multi-locus phylogenetic study of the genus suggested that the cupulate group of Helvella was in need of comprehen- sive revision. In this study, all the specimens of cupulate Helvella sensu lato with ribbed stipes deposited in HMAS were examined morphologically and molecularly. -

Final Report 1

Sand pit for Biodiversity at Cep II quarry Researcher: Klára Řehounková Research group: Petr Bogusch, David Boukal, Milan Boukal, Lukáš Čížek, František Grycz, Petr Hesoun, Kamila Lencová, Anna Lepšová, Jan Máca, Pavel Marhoul, Klára Řehounková, Jiří Řehounek, Lenka Schmidtmayerová, Robert Tropek Březen – září 2012 Abstract We compared the effect of restoration status (technical reclamation, spontaneous succession, disturbed succession) on the communities of vascular plants and assemblages of arthropods in CEP II sand pit (T řebo ňsko region, SW part of the Czech Republic) to evaluate their biodiversity and conservation potential. We also studied the experimental restoration of psammophytic grasslands to compare the impact of two near-natural restoration methods (spontaneous and assisted succession) to establishment of target species. The sand pit comprises stages of 2 to 30 years since site abandonment with moisture gradient from wet to dry habitats. In all studied groups, i.e. vascular pants and arthropods, open spontaneously revegetated sites continuously disturbed by intensive recreation activities hosted the largest proportion of target and endangered species which occurred less in the more closed spontaneously revegetated sites and which were nearly absent in technically reclaimed sites. Out results provide clear evidence that the mosaics of spontaneously established forests habitats and open sand habitats are the most valuable stands from the conservation point of view. It has been documented that no expensive technical reclamations are needed to restore post-mining sites which can serve as secondary habitats for many endangered and declining species. The experimental restoration of rare and endangered plant communities seems to be efficient and promising method for a future large-scale restoration projects in abandoned sand pits. -

Research Article Chemical, Bioactive, and Antioxidant Potential of Twenty Wild Culinary Mushroom Species

Hindawi Publishing Corporation BioMed Research International Volume 2015, Article ID 346508, 12 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/346508 Research Article Chemical, Bioactive, and Antioxidant Potential of Twenty Wild Culinary Mushroom Species S. K. Sharma1 and N. Gautam2 1 Department of Plant Pathology, CSK, Himachal Pradesh Agriculture University, Palampur 176 062, India 2Centre for Environmental Science and Technology, School of Environment and Earth Sciences, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda 151 001, India Correspondence should be addressed to N. Gautam; [email protected] Received 8 May 2015; Accepted 11 June 2015 Academic Editor: Miroslav Pohanka Copyright © 2015 S. K. Sharma and N. Gautam. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The chemical, bioactive, and antioxidant potential of twenty wild culinary mushroom species being consumed by the peopleof northern Himalayan regions has been evaluated for the first time in the present study. Nutrients analyzed include protein, crude fat, fibres, carbohydrates, and monosaccharides. Besides, preliminary study on the detection of toxic compounds was done on these species. Bioactive compounds evaluated are fatty acids, amino acids, tocopherol content, carotenoids (-carotene, lycopene), flavonoids, ascorbic acid, and anthocyanidins. Fruitbodies extract of all the species was tested for different types of antioxidant assays. Although differences were observed in the net values of individual species all the species were found to be rich in protein, and carbohydrates and low in fat. Glucose was found to be the major monosaccharide. Predominance of UFA (65–70%) over SFA (30–35%) was observed in all the species with considerable amounts of other bioactive compounds. -

Impact of Aphid Colony Size and Associated Induced Plant Vola Tiles on Searching and Oviposition Behaviour of a Predatory Hoverfly

Belgian Journal ofEntomology I 0 (2008) : 17-26 Impact of aphid colony size and associated induced plant vola tiles on searching and oviposition behaviour of a predatory hoverfly Almohamad RAKI, Fran~ois J. VERHEGGEN, Frederic FRANCIS & Eric HAUBRUGE Department of Functional and evolutionary Entomology, Passage des Deportes 2, B-5030 Gembloux (Belgium). Corresponding author: Almohamad Raki, Department of Functional & Evolutionary Entomology, Gembloux Agricultural University, Passage des Deportes 2, B-5030 Gembloux (Belgium), Phone: +32(0)81.622346, Fax: +32(0)81.622312, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Volatile chemicals emitted by aphids or aphid-infested plants act as kairomonal substances for several aphid natural enemies, and are therefore considered as indirect defence for the infested plants. In the present study, the foraging and oviposition behaviour of the aphid specific predator, Episyrphus balteatus DEGEER (Diptera: Syrphidae), was investigated with respect to the aphid colony size, using a leaf disc bioassay. Female E. balteatus exhibited pronounced searching and acceptance behaviour, leading to egg laying, in response to large Myzus persicae Sulzer (Homoptera: Aphididae) colony sizes. Behavioural impacts of synthetic aphid alarm pheromone and geranyl acetone toward E. balteatus female foraging and oviposition behaviour were also demonstrated in this work. These results highlight the role of aphid semiochemicals in predatory hoverfly attraction and provided an opportunity to elucidate some mechanisms of decision-making by female syrphid predators during their foraging and egg-laying behaviour. Keywords: Episyrphus balteatus, foraging behaviour, Myzus persicae, (E)-P famesene, geranyl acetone Introduction Volatile chemical signals released by herbivore-infested plants serve as olfactory cues for parasitoids (Du et al., I998; DE MORAES et al., I998; VAN LOON et al., 2000) and predators (EVANS & DIXON, 1986; DICKE, 1999; NINKOVIC et al., 2001).