Frank Lloyd Wright and the Destruction of the Box Author(S): H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zimmerman House Materials—Final List Binder 1

Zimmerman House Materials—Final List Binder 1—Labeled “Zimmerman House Through 1989” Photocopied articles from magazines and newspapers o Dates: from 1956-1989, bulk 1989 Binder 2—Labeled “Zimmerman House 1990” Photocopied and original articles from magazines and newspapers o Date: 1990 Binder 3—Labeled “Zimmerman House 1991” Photocopied and original articles from magazines and newspapers o Dates: 1991-1992, bulk 1991 Box 1—Labeled “Zimmerman House Archive—Deaccession? Files” Folder: Sotheby’s catalogue—Gagliano violin and sales slip Folder: Slides, photos, receipts, correspondence, appraisal for Gagliano violin and bow. o Date: 1989 Box 2—Labeled “Zimmerman House Archive—Vintage Publications on the Zimmerman House” “The Zimmerman House Historic Structure Report” (2 copies); also includes a press release (not attached) o Date: 1989 “A Classic Usonian: Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1950 House for Isadore J. and Lucille Zimmerman.” General information, labels. o Date: 1990 Folder: “Exhibition: A Classic Usonian: Label Copy.” Also an unattached article; label copy from exhibit appears to be the same as previous item. “Currier Grant Application for National Endowment for the Humanities for Training Zimmerman House Guides.” Also includes unattached correspondence, a docent bulletin, a memorandum, and a priorities evaluation. o Dates: 1990-1991, bulk 1990 Box 3—Labeled “Uncatalogued Materials” Newsclipping about Dr. Zimmerman o Date: undated 2 color photos of exterior of Zimmerman House with inscriptions from Zimmermans on back o Date: 1976 Black and white photo of exterior of Zimmerman House in winter o Date: undated 3 B & W photos of Lucille Zimmerman’s family o Date: undated Postcard with picture of S.C. -

MODERN ARCHITECTURE INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION I, Momaexh 0015 Masterchecklist

BaM-- fu-- ~~{S~ MODERN ARCHITECTURE INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION I, MoMAExh_0015_MasterChecklist NEW YORK FEB. 10 TO MARCH 23,1932 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART PHOTOGRAPHS IN THE EXHIBITION ILLUSTRATING THE EXTENT OF MODERN ARCHITECTURE AUSTRIA LOIS WELZENBACHER:Apartment House, Innsbruck. 1930. BELGIUM H. L. DEKONINCK:Lenglet House, Uccle, near Brussels. 1926. MoMAExh_0015_MasterChecklist CZECHOSLOVAKIA I OTTO EISLER:House for Two Brothers, Brno, 1931. BOHUSLAVFucns: Students' Clubhouse, Brno. 1931. I I LUDVIKKYSELA:Bata Store, Prague. 1929. ENGLAND AMYAS CONNELL:House in Amersham, Buckinghamshire. 193I. JOSEPHEMBERTON:Royal Corinthian Yacht Club, Burnham-an-Crouch. 1931. FINLAND o ALVAR AALTO: Turun Sanomat Building, Abo. 1930. FRANCE Gabriel Guevrekian: Villa Heim, Neuilly-sur-Seine. 1928. ANDRE LURyAT:Froriep de Salis House, Boulogne-sur-Seine. 1927. ANDRE LURCAT:Hotel Nord-Sud, Calvi, Corsica. 1931. 2!j ,I I I I I I FRANCE (continued) ROBMALLET-STEVENS:de Noailles Villa, Hyeres. "925. PAULNELSON: Pharmacy, Paris. 1931. GERMANY OTTOHAESLER: Old People's Home, Kassel. 1931. LUCKHARDT&' ANKER: Row of Houses, Berlin. "929. ERNSTMAY &' ASSOCIATES:Friedrich Ebert School, Frankfort-on-Main. 1931. 28 0 MoMAExh_0015_MasterChecklist ERICHMENDELSOHN:Schocken Department Store, Chemnitz. "9 -3 . ERICHMENDELSOHN:House of the Architect, Berlin. "930. HANSSCHAROUN: "Wohnheim;" Breslau. 1930. KARLSCHNEIDER:Kunstverein, Hamburg. "930. HOLLAND BRINKMAN&' VAN DERVLUGT: Van Nelle Factory, Rotterdam. 1928-30. I I W, J. DUIKER: Open Air School, Amsterdam. "931. G. RIETVELD:House at Utrecht. "924. ITALY 1. FIGINI &' G. POLLIN!:Electrical House at the Monza Exposition. "930. I' JAPAN ISABUROUENO: Star Bar, Kioto. "931. MAMORU YAMADA: Electrical Laboratory, Tokio. "930. SPAIN LABAYEN&' AIZPUR1JA:Club House, San Sebastian. "930. 26 SWEDEN SVEN MARKELlus &' UNO AHREN: Students' Clubhouse, Stockholm. -

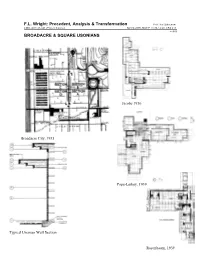

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Frank_... Frank Lloyd Wright From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Frank Lloyd Wright (born Frank Lincoln Wright, June 8, 1867 – April 9, Frank Lloyd Wright 1959) was an American architect, interior designer, writer and educator, who designed more than 1000 structures and completed 532 works. Wright believed in designing structures which were in harmony with humanity and its environment, a philosophy he called organic architecture. This philosophy was best exemplified by his design for Fallingwater (1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture".[1] Wright was a leader of the Prairie School movement of architecture and developed the concept of the Usonian home, his unique vision for urban planning in the United States. His work includes original and innovative examples of many different building types, including offices, churches, schools, Born Frank Lincoln Wright skyscrapers, hotels, and museums. Wright June 8, 1867 also designed many of the interior Richland Center, Wisconsin elements of his buildings, such as the furniture and stained glass. Wright Died April 9, 1959 (aged 91) authored 20 books and many articles and Phoenix, Arizona was a popular lecturer in the United Nationality American States and in Europe. His colorful Alma mater University of Wisconsin- personal life often made headlines, most Madison notably for the 1914 fire and murders at his Taliesin studio. Already well known Buildings Fallingwater during his lifetime, Wright was recognized Solomon R. Guggenheim in 1991 by the American Institute of Museum Architects as "the greatest American Johnson Wax Headquarters [1] architect of all time." Taliesin Taliesin West Robie House Contents Imperial Hotel, Tokyo Darwin D. -

Aspectos Da Arquitetura Orgânica De Frank Lloyd Wright Na Arquitetura Paulista

Débora Fabbri Foresti Aspectos da arquitetura orgânica de Frank Lloyd Wright na arquitetura paulista A obra de José Leite de Carvalho e Silva São Carlos 2008 Débora Fabbri Foresti Aspectos da arquitetura orgânica de Frank Lloyd Wright na arquitetura paulista A obra de José Leite de Carvalho e Silva Dissertação de Mestrado Orientador: Prof. Dr. Renato Luis Sobral Anelli Área de concentração: Teoria e História da Arquitetura Dissertação apresentada ao Departamento de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Escola de Engenharia de São Carlos da Universidade de São Paulo para a obtenção do grau de Mestre São Carlos 2008 AUTORIZO A REPRODUÇÃO E DIVULGAÇÃO TOTAL OU PARCIAL DESTE TRABALHO, POR QUALQUER MEIO CONVENCIONAL OU ELETRÔNICO, PARA FINS DE ESTUDO E PESQUISA, DESDE QUE CITADA A FONTE. Ficha catalográfica preparada pela Seção de Tratamento da Informação do Serviço de Biblioteca – EESC/USP Foresti, Débora Fabbri F718a Aspectos da arquitetura orgânica de Frank Lloyd Wright na arquitetura paulista : a obra de José Leite de Carvalho e Silva / Débora Fabbri Foresti ; orientador Renato Luis Sobral Anelli. –- São Carlos, 2008. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo e Área de Concentração em Teoria e História da Arquitetura -- Escola de Engenharia de São Carlos da Universidade de São Paulo. 1. Arquitetura Moderna. 2. Organicismo. 3. Arquitetura paulista. 4. Silva, José Leite de Carvalho e. I. Título. Para os meus pais AGRADECIMENTOS Ao Prof. Dr. Renato Anelli, pela orientação e por abrir caminhos ao me apresentar o arquiteto Carvalho e Silva. Ao Prof. Dr. Paulo Fujioka, pelo aprendizado, pela paciência e extrema atenção a cada detalhe. -

Donald Langmead

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT: A Bio-Bibliography Donald Langmead PRAEGER FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT Recent Titles in Bio-Bibliographies in Art and Architecture Paul Gauguin: A Bio-Bibliography Russell T. Clement Henri Matisse: A Bio-Bibliography Russell T. Clement Georges Braque: A Bio-Bibliography Russell T. Clement Willem Marinus Dudok, A Dutch Modernist: A Bio-Bibliography Donald Langmead J.J.P Oud and the International Style: A Bio-Bibliography Donald Langmead FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT A Bio-Bibliography Donald Langmead Bio-Bibliographies in Art and Architecture, Number 6 Westport, Connecticut London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Langmead, Donald. Frank Lloyd Wright : a bio-bibliography / Donald Langmead. p. cm.—(Bio-bibliographies in art and architecture, ISSN 1055-6826 ; no. 6) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0–313–31993–6 (alk. paper) 1. Wright, Frank Lloyd, 1867–1959—Bibliography. I. Title. II. Series. Z8986.3.L36 2003 [NA737.W7] 016.72'092—dc21 2003052890 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2003 by Donald Langmead All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2003052890 ISBN: 0–313–31993–6 ISSN: 1055–6826 First published in 2003 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the -

The Education of the Architect

THE EDUCATION OF THE ARCHITECT Historiography, Urbanism, and the Growth ofArchitectural Knowledge Essays Presented to Stanford Anderson edited by Martha Pollak The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England .,'- r ':; 1 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT'S "THE ART AND CRAFT OF THE MACHINE": TEXT AND CONTEXT Joseph M. Siry In 1901 Frank Lloyd Wright achieved a synthesis ofboth ideas and fonTIS that would guide his individual work for the next decade and influence the course ofmodern architecture through the early twentieth century. In that year, when Wright first published the type of the prairie house, he also presented the concepts that had underlain its fonnulation in his address entitled "The Art and Craft of the Machine." This remarkable text developed ideas that had appeared in Wright's writings from 1894, just as the prairie house emerged from his experiments in domestic architecture from about 1893. Through the 1890s, Wright had assimilated a range of ideas from Chicago's architectural culture that infonned his position announced in "The Art and Craft of the Machine." These ideas also emerged in part as a response to rapid development ofthe city's building industry, whose new capacities Wright and others sought to integrate into their art. Study ofWright's address in light ofits sources and contexts clarifies its place in early modern architecture, with whose historiog raphy this text is often identified. 1 Chicago's Debate on Craft and Architecture Wright's "The Art and Craft ofthe Machine" contributed to an exchange of views within the Chicago Arts and Crafts Society created at Hull House. Founded in 1897, the society developed a local program ofinstruction, exhibi tion, and publication devoted mainly to handcrafted works and objects. -

Frank Lloyd Wright Architectural Drawing

CLIENT NAME PROJECT NO. ITEM COUNT PROJECT TITLE WORK TYPE CITY STATE DATE Ablin, Dr. George Project 5812 19 drawings Dr. George Ablin house (Bakersfield, California). House Bakersfield CA 1958 Abraham Lincoln Center Project 0010 53 drawings Abraham Lincoln Center (Chicago, Illinois). Unbuilt Project Religious Chicago IL 1900 Achuff, Harold and Thomas Carroll Project 5001 21 drawings Harold Achuff and Thomas Carroll houses (Wauwatosa, Wisconsin). Unbuilt Projects Houses Wauwatosa WI 1949 Ackerman, Lee, and Associates Project 5221 7 drawings Paradise on Wheels Trailer Park for Lee Ackerman and Associates (Paradise Valley, Arizona). Trailer Park (Paradise on Wheels) Phoenix AZ 1952 Unbuilt Project Adams, Harry Project 1105 45 drawings Harry Adams house (Oak Park, Illinois). House Oak Park IL 1912 Adams, Harry Project 1301 no drawings Harry Adams house (Oak Park, Illinois). House Oak Park IL 1913 Adams, Lee Project 5701 11 drawings Lee Adams house (Saint Paul, Minnesota). Unbuilt Project House St. Paul MN 1956 Adams, M.H. Project 0524 1 drawing M. H. Adams house (Highland Park, Illinois). Alterations, Unbuilt Project House, alterations Highland Park IL 1905 Adams, Mary M.W. Project 0501 12 drawings Mary M. W. Adams house (Highland Park, Illinois). House Highland Park IL 1905 Adams, William and Jesse Project 0001 no drawings William and Jesse Adams house (Oak Park, Illinois). House Chicago IL 1900 Adams, William and Jesse Project 0011 4 drawings William and Jesse Adams house (Oak Park, Illinois). House Longwood IL 1900 Adelman, Albert Project 4801 47 drawings Albert Adelman house (Fox Point, Wisconsin). Scheme 1, Unbuilt Project House (Scheme 1) Fox Point WI 1946 Adelman, Albert Project 4834 31 drawings Albert Adelman house (Fox Point, Wisconsin). -

Frank Lloyd Wright: Influences and Worldview Brock Stafford Olivet Nazarene University, [email protected]

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet M.A. in Philosophy of History Theses History 8-2012 Frank Lloyd Wright: Influences and Worldview Brock Stafford Olivet Nazarene University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/hist_maph Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Esthetics Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Interior Architecture Commons, Philosophy of Science Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Stafford, Brock, "Frank Lloyd Wright: Influences and Worldview" (2012). M.A. in Philosophy of History Theses. 6. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/hist_maph/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in M.A. in Philosophy of History Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frank Lloyd Wright: Influences and Worldview A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History and Political Science School of Graduate and Continuing Studies Olivet Nazarene University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Philosophy of History by Brock Stafford August 2012 1 © 2012 Brock Stafford ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 2 ^miature vase for the Masters in Philosophy of History? Thesis of Brock Stafford APPROVED BY William Dean. Department Chair Date David Van Heerost Thesis Adviser Date Curt Rice. Thesis Adviser Date Introduction Philosophy is to the mind of the architect as eyesight to his steps. The term “genius” when applied to him simply means a man who understands what others only know about. -

List of National Register Properties

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES IN ILLINOIS (As of 11/9/2018) *NHL=National Historic Landmark *AD=Additional documentation received/approved by National Park Service *If a property is noted as DEMOLISHED, information indicates that it no longer stands but it has not been officially removed from the National Register. *Footnotes indicate the associated Multiple Property Submission (listing found at end of document) ADAMS COUNTY Camp Point F. D. Thomas House, 321 N. Ohio St. (7/28/1983) Clayton vicinity John Roy Site, address restricted (5/22/1978) Golden Exchange Bank, Quincy St. (2/12/1987) Golden vicinity Ebenezer Methodist Episcopal Chapel and Cemetery, northwest of Golden (6/4/1984) Mendon vicinity Lewis Round Barn, 2007 E. 1250th St. (1/29/2003) Payson vicinity Fall Creek Stone Arch Bridge, 1.2 miles northeast of Fall Creek-Payson Rd. (11/7/1996) Quincy Coca-Cola Bottling Company Building, 616 N. 24th St. (2/7/1997) Downtown Quincy Historic District, roughly bounded by Hampshire, Jersey, 4th & 8th Sts. (4/7/1983) Robert W. Gardner House, 613 Broadway St. (6/20/1979) S. J. Lesem Building, 135-137 N. 3rd St. (11/22/1999) Lock and Dam No. 21 Historic District32, 0.5 miles west of IL 57 (3/10/2004) Morgan-Wells House, 421 Jersey St. (11/16/1977) DEMOLISHED C. 2017 Richard F. Newcomb House, 1601 Maine St. (6/3/1982) One-Thirty North Eighth Building, 130 N. 8th St. (2/9/1984) Quincy East End Historic District, roughly bounded by Hampshire, 24th, State & 12th Sts. (11/14/1985) Quincy Northwest Historic District, roughly bounded by Broadway, N. -

Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings Designated and Proposed As NHLS

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BUILDINGS DESIGNATED AS NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS AND PROPOSED FOR NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK CONSIDERATION Frank Lloyd Wright (FLW) worked on well over one thousand projects. Of these projects, an estimated 430 were seen to completion (not including work that may have been done on projects with other principal architects), and a vast majority of these are still standing.1 There has always been interest in National Historic Landmark (NHL) designation for the FLW designed buildings that remain standing today. Because of his stature in the architectural world, many owners of an FLW building believe that their property is worthy of NHL designation and they contact the NHL Program on a regular basis inquiring about the process for designating their property. To understand FLW’s work and to help NHL Program staff make sound decisions about whether FLW properties might be good candidates for NHL nomination, the NHL Program invited several FLW scholars to review the architect’s body of work. In 1998, the NHL Program asked Dr. Paul E. Sprague, Dr. Paul S. Kruty, and Mr. Randolph C. Henning, if they would undertake the task of reviewing and prioritizing FLW’s built commissions (of which approximately one in five has been lost according to the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy) and assemble a list of those extant properties that are worthy of NHL consideration. The scholars compiled a list of fifty-six FLW properties that they believed should be considered for NHL designation. The Secretary of the Interior has already designated twenty-six of these properties as NHLs. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory » Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) \ UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY » NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Highland Park ^ LOCATION STREET&Nuyg|p incorporation limits of Highland Park 40T FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Highland Park ^VICINITY OF 12 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois 012 Lake 097 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENTUSE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE J^MUSEUM —BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE ILUNOCCUPIED ^COMMERCIAL J?PARK —STRUCTURE ^EBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS ^EDUCATIONAL J£PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^ENTERTAINMENT J£RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED ^.GOVERNMENT _ SCIENTIFIC xMultiple _ BEING.GONSIDERED , X-YES: UNRESTRICTED , ^INDUSTRIAL , ., ^TRANSPORTATION Resources A5/M •• '—NO v { - . ...:...' •, •: ,_^MItlTARY , , —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME ______Multiple ownership - see continuation sheet for addresses, property STREET & NUMBER owners and PIN numbers. CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. 1 . 2. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Deerfield Township Assessor's Office West Deerfield Township STREET & NUMBER 600 Laurel Avenue Assessor s Office 858 Waukegan Road CITY. TOWN Highland Park, Illinois 60035 STATE Deerfield, Illinois REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS 60015 TiTLE 1.Highland Park Landmark Survey DATE 1979-81 FEDERAL STATE COUNTY "^LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS West Ridge Center< 6_36_Ridge Road CITY. TOWN Highland Park (see continuation sheet for buildings listed,' other survey*? NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No.1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form Continuation sheet Item number Page National Register of Historic Place Listings: (1980, U.S.