The Stylistic Characteristics of the Shampay House of 1919: a Formal Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Work of Frank Lloyd Wright

THE LIFE AND WORK OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT PART 4 Ages 42 (1909) to 47 (1914) In Italy and Wisconsin Wunderlich PhD website: http://users.etown.edu/w/wunderjt/ Architecture Portfolio 8/28/2018 PART 1: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 0-19 (1867-1886) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube Context: Post Civil War recession. Industrial Revolution. Farm life. Preacher/Musician-Father, Teacher-Mother. Mother’s large influential Unitarian family of Welsh farmers. Nature. Parent’s divorce. Architecture: Froebel schooling (e.g., blocks). Barns/farm-houses (PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube). Organic Architecture roots. PART 2: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 20-33 (1887-1900) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube. Context: Rebuilding Chicago after the Great Fire. Wife Catherine and first five children. Architecture: Architects Joseph Silsbee and Louis Sullivan. Oak Park. Home & Studio. “Organic Architecture” begins. PART 3: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 34-41 (1901-1908) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube. Context: First Japan trip (PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube). Arts & Crafts movements. Six children. Architecture: Prairie Style. Oak Park & River Forest, Unity Temple, Robie House, Larkin Building. PART 4: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 42-47 (1909-1914) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube THIS LECTURE Context: Runs off with Mistress. Lives in Italy (Page MP4 YouTube). Builds Taliesin on family farmland. Mistress murdered. Architecture: Wasmuth Portfolio published(Germany).Taliesin. Many operable windows for health & passive cooling. Sculptures. PART 5: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 48-62 (1915-1929) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube Context: WWI, Roaring 20’s. Short 2nd marriage. Lives 3 yrs in Japan, then California and Wisconsin. -

A Rccaarchitecture California the Journal of the American Institute Of

architecture california the journal of the american institute of architects california council a r cCA aiacc design awards issue 04.3 photo finish ❉ Silent Archives ❉ AIACC Member Photographs ❉ The Subject is Architecture arcCA 0 4 . 3 aiacc design a wards issue p h o t o f i n i s h Co n t e n t Tracking the Awards 8 Value of the 25 Year Award 10 ❉ Eric Naslund, FAIA Silent Archives: 14 In the Blind Spot of Modernism ❉ Pierluigi Serraino, Assoc. AIA AIACC Member Photographs 18 ❉ AIACC membership The Subject is Architecture 30 ❉ Ruth Keffer AIACC 2004 AWARDS 45 Maybeck Award: 48 Daniel Solomon, FAIA Firm of the Year Award: 52 Marmol Radziner and Associates Lifetime Achievement 56 Award: Donlyn Lyndon, FAIA ❉ Interviewed by John Parman Lifetime Achievement 60 Award: Daniel Dworsky, FAIA ❉ Interviewed by Christel Bivens Kanda Design Awards 64 Reflections on the Awards 85 Jury: Eric Naslund, FAIA, and Hugh Hardy, FAIA ❉ Interviewed by Kenneth Caldwell Savings By Design A w a r d s 88 Co m m e n t 03 Co n t r i b u t o r s 05 C r e d i t s 9 9 Co d a 1 0 0 1 arcCA 0 4 . 3 Editor Tim Culvahouse, AIA a r c C A is dedicated to providing a forum for the exchange of ideas among mem- bers, other architects and related disciplines on issues affecting California archi- Editorial Board Carol Shen, FAIA, Chair tecture. a r c C A is published quarterly and distributed to AIACC members as part of their membership dues. -

Graycliff – a Truly American Story “In His Unshakable Optimism

Graycliff – A Truly American Story “In his unshakable optimism, messianic zeal, and pragmatic resilience, Wright was quintessentially American.” ‐ Smithsonian magazine tribute on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Guggenheim. Just as it is often said that Frank Lloyd Wright was truly American in spirit and style, the Graycliff story is woven out of strands that also have a truly American flavor. The American Dream, embodying the notion of opportunity for all, takes shape here in the true-to-life rags-to-riches story of Darwin Martin. The close cousin to the American Dream – the one that holds that through gumption and perseverance one may triumph – is on display as well. Perseverance, resilience, and the comeback story are all in evidence at various stages in Graycliff’s 90 years – for the Martins, for Wright himself, for the house, the region, and for the Graycliff Conservancy as an organization. Win-win relationships where all parties pragmatically get their needs met are both a hallmark of American history and culture and a defining characteristic of relationships at Graycliff where all the key players compromised a little while holding onto their defining principles in the end. One of the most enduring and distinctive American values is the lure and promise of nature, wilderness, and the frontier and the potential of new beginnings that are implicit in the purity of nature and the fresh start that movement to a new place makes possible. This is evident in both the post-retirement reboot for the Martin family at Graycliff and the property’s roots in organic architecture in which the house rose from the lands on which it sits. -

Zimmerman House Materials—Final List Binder 1

Zimmerman House Materials—Final List Binder 1—Labeled “Zimmerman House Through 1989” Photocopied articles from magazines and newspapers o Dates: from 1956-1989, bulk 1989 Binder 2—Labeled “Zimmerman House 1990” Photocopied and original articles from magazines and newspapers o Date: 1990 Binder 3—Labeled “Zimmerman House 1991” Photocopied and original articles from magazines and newspapers o Dates: 1991-1992, bulk 1991 Box 1—Labeled “Zimmerman House Archive—Deaccession? Files” Folder: Sotheby’s catalogue—Gagliano violin and sales slip Folder: Slides, photos, receipts, correspondence, appraisal for Gagliano violin and bow. o Date: 1989 Box 2—Labeled “Zimmerman House Archive—Vintage Publications on the Zimmerman House” “The Zimmerman House Historic Structure Report” (2 copies); also includes a press release (not attached) o Date: 1989 “A Classic Usonian: Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1950 House for Isadore J. and Lucille Zimmerman.” General information, labels. o Date: 1990 Folder: “Exhibition: A Classic Usonian: Label Copy.” Also an unattached article; label copy from exhibit appears to be the same as previous item. “Currier Grant Application for National Endowment for the Humanities for Training Zimmerman House Guides.” Also includes unattached correspondence, a docent bulletin, a memorandum, and a priorities evaluation. o Dates: 1990-1991, bulk 1990 Box 3—Labeled “Uncatalogued Materials” Newsclipping about Dr. Zimmerman o Date: undated 2 color photos of exterior of Zimmerman House with inscriptions from Zimmermans on back o Date: 1976 Black and white photo of exterior of Zimmerman House in winter o Date: undated 3 B & W photos of Lucille Zimmerman’s family o Date: undated Postcard with picture of S.C. -

MODERN ARCHITECTURE INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION I, Momaexh 0015 Masterchecklist

BaM-- fu-- ~~{S~ MODERN ARCHITECTURE INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION I, MoMAExh_0015_MasterChecklist NEW YORK FEB. 10 TO MARCH 23,1932 MUSEUM OF MODERN ART PHOTOGRAPHS IN THE EXHIBITION ILLUSTRATING THE EXTENT OF MODERN ARCHITECTURE AUSTRIA LOIS WELZENBACHER:Apartment House, Innsbruck. 1930. BELGIUM H. L. DEKONINCK:Lenglet House, Uccle, near Brussels. 1926. MoMAExh_0015_MasterChecklist CZECHOSLOVAKIA I OTTO EISLER:House for Two Brothers, Brno, 1931. BOHUSLAVFucns: Students' Clubhouse, Brno. 1931. I I LUDVIKKYSELA:Bata Store, Prague. 1929. ENGLAND AMYAS CONNELL:House in Amersham, Buckinghamshire. 193I. JOSEPHEMBERTON:Royal Corinthian Yacht Club, Burnham-an-Crouch. 1931. FINLAND o ALVAR AALTO: Turun Sanomat Building, Abo. 1930. FRANCE Gabriel Guevrekian: Villa Heim, Neuilly-sur-Seine. 1928. ANDRE LURyAT:Froriep de Salis House, Boulogne-sur-Seine. 1927. ANDRE LURCAT:Hotel Nord-Sud, Calvi, Corsica. 1931. 2!j ,I I I I I I FRANCE (continued) ROBMALLET-STEVENS:de Noailles Villa, Hyeres. "925. PAULNELSON: Pharmacy, Paris. 1931. GERMANY OTTOHAESLER: Old People's Home, Kassel. 1931. LUCKHARDT&' ANKER: Row of Houses, Berlin. "929. ERNSTMAY &' ASSOCIATES:Friedrich Ebert School, Frankfort-on-Main. 1931. 28 0 MoMAExh_0015_MasterChecklist ERICHMENDELSOHN:Schocken Department Store, Chemnitz. "9 -3 . ERICHMENDELSOHN:House of the Architect, Berlin. "930. HANSSCHAROUN: "Wohnheim;" Breslau. 1930. KARLSCHNEIDER:Kunstverein, Hamburg. "930. HOLLAND BRINKMAN&' VAN DERVLUGT: Van Nelle Factory, Rotterdam. 1928-30. I I W, J. DUIKER: Open Air School, Amsterdam. "931. G. RIETVELD:House at Utrecht. "924. ITALY 1. FIGINI &' G. POLLIN!:Electrical House at the Monza Exposition. "930. I' JAPAN ISABUROUENO: Star Bar, Kioto. "931. MAMORU YAMADA: Electrical Laboratory, Tokio. "930. SPAIN LABAYEN&' AIZPUR1JA:Club House, San Sebastian. "930. 26 SWEDEN SVEN MARKELlus &' UNO AHREN: Students' Clubhouse, Stockholm. -

Download Pamphlets on Labor Law, Tort Immunity and Other Subjects from the Ancel Glink Library

OCTOBER 2011 | VOLUME XXIX ISSUE 5 ILLINOIS LIBRARY ASSOCIATION ILLINOIS LIBRARY The Illinois Library Association Reporter is a forum for those who are improving and reinventing Illinois libraries, with articles that seek to: explore new ideas and practices from all types of libraries and library systems; examine the challenges facing the profession; and inform the library community and its supporters with news and comment about important issues. The ILA Reporter is produced and circulated with the purpose of enhancing and supporting the value of libraries, which provide free and equal access to information. This access is essential for an open democratic society, an informed electorate, and the advancement of knowledge for all people. ON THE COVER This drawing of the interior of the B. Harley Bradley House in Kankakee is among the drawings in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Wasmusth Portfolio in the special collections of the Oak Park Public Library. The house was designed in 1900 for Harley and Anna Hickox Bradley, arguably Wright’s first acknowledged Prairie-style design. Built along the Kankakee River, it’s a perfect example of Wright’s idea to design an entire house including the interiors as well. See article beginning on page 8. The Illinois Library Association is the voice for Illinois libraries and the millions who depend The Illinois Library Association has three full-time staff members. It is governed by on them. It provides leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of a sixteen-member executive board, made up of elected officers. The association library services in Illinois and for the library community in order to enhance learning and employs the services of Kolkmeier Consulting for legislative advocacy. -

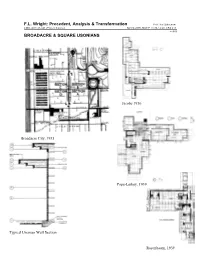

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

Frank Lloyd Wright 978-2-86364-338-9 Cinq Approches ISBN / Approches Cinq

frank lloydwright DANIEL TREIBER DANIEL 978-2-86364-338-9 PARENTHÈSES ISBN cinq approches / approches cinq Wright, Lloyd Frank / Treiber Daniel www.editionsparentheses.com www.editionsparentheses.com WRIGHT, JUSQU’À NOUS Dans ce nouveau livre que je consacre à Frank Lloyd Wright, je me propose d’aborder son œuvre selon cinq approches différentes. 978-2-86364-338-9 L’essai introductif est une présentation de ensemble de ses travaux à travers une lecture des renver- l’ ISBN / sements opérés par chaque nouvelle « période » par rapport à la précédente. Wright a vécu jusqu’à près de 90 ans et, approches tout au long de sa longue vie, l’architecte américain s’est cinq montré capable de se renouveler d’une manière specta- culaire. Plusieurs « styles » se partagent en effet l’œuvre : Wright, une première période presque Art nouveau, une deuxième Lloyd plus singulière et souvent considérée comme un peu énig- Frank matique, d’une ornementation encore plus foisonnante, / puis, enfin, une période délibérément moderne avec la Treiber production d’icônes de l’architecture, la Maison sur la cascade et le musée Guggenheim. La deuxième approche est consacrée au « côté Daniel Ruskin » de Wright. Le grand historien américain Henry-Russell Hitchcock a déclaré dans son Architecture : XIXe et XXe siècles que ce qui faisait la « profonde diffé- rence » entre Frank Lloyd Wright et Auguste Perret, un autre novateur quasiment de la même génération, était que 7 www.editionsparentheses.com www.editionsparentheses.com « l’un avait dans le sang la tradition du néogothique anglais exponentielle de notre environnement, c’est le point par — en bonne part due à ses lectures de Ruskin — tandis lequel les préoccupations de Wright sont étonnamment que l’autre ne l’avait pas ». -

Space of Continuity: Frank Lloyd Wright's Destruction of the Box And

Space of Continuity: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Destruction of the Box and Modern Conceptions of Space Late 19th-early 20th century America was an era of confluence of science, phi- losophy and religion: a contemporary polemic that equated religion (belief based on faith) with science (knowledge based on empirical data of physical phe- nomena). Modernity in 20th century America would be shaped by a pervasive theosophical atmosphere that coupled science with religion to cause a recon- sideration of mental/spiritual relationships and a redefinition of space/time concepts. Theosophy’s introduction of Eastern metaphysics to Western culture revealed possibilities of an inner self with respect to the outer being and opened the way to conceive of inner space, or interiority, and as a result interior space in buildings. To follow is a reconsideration of Wright’s work with respect to the theosophical and occult influences that guided his thinking. His contribution to today’s notion of architecture as a space of continuity will be demonstrated through case studies of his work beginning with the early Dana House (begun in 1899) to the Guggenheim Museum (completed after his death in 1959). EUGENIA VICTORIA ELLIS THE RED SQUARE Drexel University Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) began his practice in 1893 after being fired for “moonlighting” near the end of his five year contract with Adler and Sullivan, one of the then-preeminent Chicago architecture firms. Originally hired to draw the delicate ornamental details of the Auditorium Building interior, another ornamental masterpiece Wright had detailed just debuted at the World’s Columbian Exposition. -

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Frank_... Frank Lloyd Wright From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Frank Lloyd Wright (born Frank Lincoln Wright, June 8, 1867 – April 9, Frank Lloyd Wright 1959) was an American architect, interior designer, writer and educator, who designed more than 1000 structures and completed 532 works. Wright believed in designing structures which were in harmony with humanity and its environment, a philosophy he called organic architecture. This philosophy was best exemplified by his design for Fallingwater (1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture".[1] Wright was a leader of the Prairie School movement of architecture and developed the concept of the Usonian home, his unique vision for urban planning in the United States. His work includes original and innovative examples of many different building types, including offices, churches, schools, Born Frank Lincoln Wright skyscrapers, hotels, and museums. Wright June 8, 1867 also designed many of the interior Richland Center, Wisconsin elements of his buildings, such as the furniture and stained glass. Wright Died April 9, 1959 (aged 91) authored 20 books and many articles and Phoenix, Arizona was a popular lecturer in the United Nationality American States and in Europe. His colorful Alma mater University of Wisconsin- personal life often made headlines, most Madison notably for the 1914 fire and murders at his Taliesin studio. Already well known Buildings Fallingwater during his lifetime, Wright was recognized Solomon R. Guggenheim in 1991 by the American Institute of Museum Architects as "the greatest American Johnson Wax Headquarters [1] architect of all time." Taliesin Taliesin West Robie House Contents Imperial Hotel, Tokyo Darwin D. -

Aspectos Da Arquitetura Orgânica De Frank Lloyd Wright Na Arquitetura Paulista

Débora Fabbri Foresti Aspectos da arquitetura orgânica de Frank Lloyd Wright na arquitetura paulista A obra de José Leite de Carvalho e Silva São Carlos 2008 Débora Fabbri Foresti Aspectos da arquitetura orgânica de Frank Lloyd Wright na arquitetura paulista A obra de José Leite de Carvalho e Silva Dissertação de Mestrado Orientador: Prof. Dr. Renato Luis Sobral Anelli Área de concentração: Teoria e História da Arquitetura Dissertação apresentada ao Departamento de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Escola de Engenharia de São Carlos da Universidade de São Paulo para a obtenção do grau de Mestre São Carlos 2008 AUTORIZO A REPRODUÇÃO E DIVULGAÇÃO TOTAL OU PARCIAL DESTE TRABALHO, POR QUALQUER MEIO CONVENCIONAL OU ELETRÔNICO, PARA FINS DE ESTUDO E PESQUISA, DESDE QUE CITADA A FONTE. Ficha catalográfica preparada pela Seção de Tratamento da Informação do Serviço de Biblioteca – EESC/USP Foresti, Débora Fabbri F718a Aspectos da arquitetura orgânica de Frank Lloyd Wright na arquitetura paulista : a obra de José Leite de Carvalho e Silva / Débora Fabbri Foresti ; orientador Renato Luis Sobral Anelli. –- São Carlos, 2008. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo e Área de Concentração em Teoria e História da Arquitetura -- Escola de Engenharia de São Carlos da Universidade de São Paulo. 1. Arquitetura Moderna. 2. Organicismo. 3. Arquitetura paulista. 4. Silva, José Leite de Carvalho e. I. Título. Para os meus pais AGRADECIMENTOS Ao Prof. Dr. Renato Anelli, pela orientação e por abrir caminhos ao me apresentar o arquiteto Carvalho e Silva. Ao Prof. Dr. Paulo Fujioka, pelo aprendizado, pela paciência e extrema atenção a cada detalhe. -

Prefabrication and the Post-War House

142 WITHOUT A HITCH: NEW DIRECTIONS IN PREFABRICATED ARCHITECTURE haps the most important, because it is the principal and most intimately connected with Prefabrication and the environmental conditioning of human beings, is everything we mean when we say the word Postwar House: the “HOUSE.” It is here that we come closest to California manifesto the heart of man’s existence; it is here that he hopes for the satisfaction of his most human needs; it is here that he strikes the firmest roots into the ground; it is here that he achieves his strongest sense of reality not only in terms of things but also in terms of fellow human beings. It is first then to “the house of man” that we must bring the abundant gifts of this age of science in the service of mankind, Matthew W. Fisher realizing that in the word “HOUSE” we encom- Iowa State University pass the full range of those activities and aspi- rations that make one man know all men as himself.”1 In July 1944, a year prior to the cessation of World War II, the California-based journal Arts and Architecture published what was in es- sence a manifesto on the “post-war house” and the opportunities and necessity for prefabrica- tion. This was largely the work of John En- tenza, publisher and editor of Arts and Archi- tecture since the late-Thirties, and his editorial assistants, Charles and Ray Eames, with sig- nificant contributions from Eero Saarinen and Buckminster Fuller, among others. Entenza and his editors were fully aware at the time of the pent-up demand for new housing that awaited the end of the war.