Robie House - Guided Interior Tour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Did Frank Lloyd Wright Establish a New Canon of American

“ The mother art is architecture. Without an architecture of our own we have no soul of our own civilization.” -Frank Lloyd Wright How did Frank Lloyd Wright establish a new canon of American architecture? Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) •Considered an architectural/artistic genius and THE best architect of last 125 years •Designed over 800 buildings •Known for ‘Prairie Style’ (really a movement!) architecture that influenced an entire group of architects •Believed in “architecture of democracy” •Created an “organic form of architecture” Prairie School The term "Prairie School" was coined by H. Allen Brooks, one of the first architectural historians to write extensively about these architects and their work. The Prairie school shared an embrace of handcrafting and craftsmanship as a reaction against the new assembly line, mass production manufacturing techniques, which they felt created inferior products and dehumanized workers. However, Wright believed that the use of the machine would help to create innovative architecture for all. From your architectural samples, what may we deduce about the elements of Wright’s work? Prairie School • Use of horizontal lines (thought to evoke native prairie landscape) • Based on geometric forms . Flat or hipped roofs with broad overhanging eaves . “Environmentally” set: elevations, overhangs oriented for ventilation . Windows grouped in horizontal bands called ribbon fenestration that used shifting light . Window to wall ratio affected exterior & interior . Overhangs & bays reach out to embrace . Integration with the landscape…Wright designed inside going out . Solid construction & indigenous materials (brick, wood, terracotta, stucco…natural materials) . Open continuous plan & spaces; use of dissolving walls, but connected spaces Prairie School •Designed & used “glass screens” that echoed natural forms •Created Usonian homes for the “masses” Frank Lloyd Wright, Darwin D. -

Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2015–2016 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program The Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Program includes 30 historic sites across the United States. FLWR on your membership card indicates that you enjoy the National Reciprocal sites benefit. Benefits vary from site to site. Please check websites listed in this brochure for detailed information on each site. ALABAMA ARIZONA CALIFORNIA FLORIDA 1 Rosenbaum House 2 Taliesin West 3 Hollyhock House 4 Florida Southern College 601 RIVERVIEW DRIVE 12621 N. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BLVD BARNSDALL PARK 750 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT WAY FLORENCE, AL 35630 SCOTTSDALE, AZ 85261-4430 4800 HOLLYWOOD BLVD LAKELAND, FL 33801 256.718.5050 480.860.2700 LOS ANGELES, CA 90027 863.680.4597 ROSENBAUMHOUSE.COM FRANKLLOYDWRIGHT.ORG 323.644.6269 FLSOUTHERN.EDU/FLW WRIGHTINALABAMA.COM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION BARNSDALL.ORG FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: 9AM–4PM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: TOUR HOURS: BOOKSHOP HOURS: 8:30AM–6PM TOUR HOURS: THURS–SUN, 11AM–4PM OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT TOUR TICKETS AVAILABLE AT THE THANKSGIVING, CHRISTMAS AND NEW Experience firsthand Frank Lloyd MAJOR HOLIDAYS. HOLLYHOCK HOUSE VISITOR’S CENTER YEAR’S DAY. 10AM–4PM Wright’s brilliant ability to integrate TUES–SAT, 10AM–4PM IN BARNSDALL PARK. VISITOR CENTER & GIFT SHOP HOURS: SUN, 1PM–4PM indoor and outdoor spaces at Taliesin Hollyhock House is Wright’s first 9:30AM–4:30PM West—Wright’s winter home, school The Rosenbaum House is the only Los Angeles project. Built between and studio from 1937-1959, located Discover the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright-designed 1919 and 1923, it represents his on 600 acres of dramatic desert. -

The 20Th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright National Locator Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois

The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright National Locator Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois 87.800° W 87.795° W 87.790° W Erie St N Grove Ave Grove N 41.8902° N, 87.7947° W Ontario St 41.8901° N, 87.7992° W E E 41.890° N 41.890° N Austin Garden Park Scoville Park N Euclid Ave Euclid N N Linden Ave Linden N Forest Ave Forest N Oak Park Ave Park Oak N N Kenilworth Ave Kenilworth N Lake St Unity Temple ! 41.888° N 41.888° N E 41.8878° N, 87.7995° W E North Blvd 41.8874° N, 87.7946° W South Blvd 41.886° N 41.886° N Home Ave Home S Grove Ave Grove S S Euclid Ave Euclid S S Clinton Ave Clinton S S Wesley Ave Wesley S S Oak Park Ave Park Oak S S Kenilworth Ave Kenilworth S 87.800° W 87.795° W Pleasant St 87.790° W Nominated National Historic Projection: Lambert Conformal Conic 1:4,500 Green Space/Park Datum: North American Datum 1983 Property Landmark Production Date: October 2015 0 100 Meters ! Gould Center, Department of Geography ¹ Buffer Zone Center Point Buildings The Pennsylvania State University Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois 87.600° W 87.598° W 87.596° W Ave Kimbark S 87.594° W 87.592° W S Woodlawn Ave Woodlawn S E 57th St 41.791° N 41.791° N S Kimbark Ave Kimbark S 41.7904° N, 87.5972° W E41.7904 N, 87.5957° W S Ellis Ave Ellis S E S Kenwood Avenue Kenwood S Frederick C. -

Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J

Architecture Publications Architecture Winter 2008 Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J. Naegele Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ arch_pubs/54. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Abstract Why "Wright in Iowa?" Are there ways that Wright's Iowa works are distinguished from his built works elsewhere? Iowa is a typical Midwest state, exceptional in neither general geography nor landscape. The ts ate's urban areas are minor, and Iowa has never been known for its subscription to avant-garde architecture. Its most renowned artist, Grant Wood, painted Iowa's rolling hills and pie-faced people in cartoon-like images that simultaneously champion and question the coalescence of people and place. Indeed, the state's most convincing buildings are found on its farms with their unpretentious, vernacular, agricultural buildings. Disciplines Architectural History and Criticism Comments This article is from Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly 19 (2008): 4–9. Posted with permission. This article is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs/54 a (Photos above and opposite page, top right) The Lowell and Agnes Walter hy "Wright in Iowa?" Are House, "Cedar Rock," Quasqueton, W there ways that Wright's Iowa. -

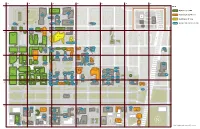

KEY KEY Last Updated: June 15, 2020

Friend Family Health Center Ronald McDonald House A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST KEY 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Building is OPEN Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S Building is COMPLETE AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Building is IN-USE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - DATE EXPECTED READY DATE AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S KIMBARK AVE S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer CollegiumJUNE 19 Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center - -

Insider's Guide

ALL THINGS visit.uchicago.edu VALOIS RESTAURANT 1518 E. 53rd St. insider’s valoisrestaurant.com President Obama’s favorite breakfast spot! They serve classic soul food for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Get guide this: they serve breakfast all day! If you forget cash for this cash-only establishment, worry not, there is an ATM Have you ever wondered what Hyde Park does inside. for fun? Sure you have! For a true taste of Hyde Park and its surrounding neighborhoods, check ORIENTAL INSTITUTE LIBRARY 1155 E. 58th St. out these not-to-be-missed South Side gems. Although Harper Memorial Library tends to attract more PROMONTORY POINT tourists and studiers alike, the Oriental Institute is home to 5491 S. South Shore Dr. a smaller, but just as beautiful reading room. Once inside, chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks/Burnham-Park/ head up the stone steps to the second floor and take a If you are looking for a great view of the lake and the right. Open 10am-5pm. Chicago skyline, or maybe just a calming place to sit and read, Promontory Point is the site to visit. A great UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PUB destination for picnics, sunsets, and people-watching, 1212 E. 59th St. “The Point” is located on Chicago’s Lake Front Trail, which Ida Noyes Hall, lower level stretches south to 95th Street and all the way north to leadership.uchicago.edu/orcsas-pub Navy Pier. Long gone are the days of indoor smoking and 50-cent cans of PBR, but “The Pub,” as it’s known on campus, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CAMPUS BOTANY maintains its status as a reliably fun place for students and botanicgarden.uchicago.edu faculty alike. -

Preserving Graycliff:An Examination of the Colors,Fabrics and Furniture of the Frank Lloyd Wright Designed Summer Residence of I

Figure 1. Graycliff exterior. 2001 WAG Postprints—Dallas, Texas Preserving Graycliff:An Examination of the Colors, Fabrics and Furniture of the Frank Lloyd Wright Designed Summer Residence of Isabelle Martin Pamela Kirschner Abstract Information was gathered in a study of the interior color scheme, fabrics and furni- ture of the Frank Lloyd Wright designed house Graycliff. The house is situated on a cliff overlooking Lake Erie in Derby, New York. It was designed by Wright in 1926 for Isabelle Martin, the wife of the industrialist Darwin Martin. Wright designed both freestanding and built-in furniture for the house interior and also suggested colors and fabrics. Extensive written documentation and original photographs found in the archives of the State University of New York at Buffalo have been utilized to determine the colors, materials and furniture original to the house. Physical evidence found on the remaining original furniture, moldings and upholstered pillows provides informa- tion about fi nishes, construction and show cover fabrics. Information on historic methods and materials from the period is provided for comparison with the physi- cal evidence along with scientifi c analysis of fi nishes. The conservation treatment methods are also discussed. This technical and historical information is helpful for conservators and curators to better understand the materials and construction used in Frank Lloyd Wright designs during this time period. It also promotes the proper care and conservation treatment of these objects while preserving original fi nishes and the historic intent of the house. Introduction Graycliff was the summer estate of Isabelle R. and Darwin D. Martin and is located on the cliffs above Lake Erie in Derby, New York, fourteen miles south of Buffalo. -

City of Chicago Analysis of Its Proposal Related to Jackson Park, Cook County, Illinois Under the Urban Parks and Recreation Recovery Act Program

City of Chicago Analysis of its Proposal Related to Jackson Park, Cook County, Illinois under the Urban Parks and Recreation Recovery Act Program November 2019 [as revised May 2020] Prepared by the City of Chicago Federal Actions In and Adjacent to Jackson Park Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 UPARR .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Statutory and Regulatory Background ....................................................................... 2 1.2.2 UPARR Grants and Program Requirements at Jackson Park ...................................... 2 1.3 Municipal Consideration of and Approval of the Proposal to Locate the OPC in Jackson Park ............................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Jackson Park and Midway Plaisance: Existing Recreation Uses and Opportunities ..................................................................................... 6 2.1 Jackson Park: Overview .......................................................................................................... 6 2.1.1 Existing Recreation Facilities....................................................................................... 8 2.1.2 Existing Recreation -

Preservation Chicago

Preservation Chicago Citizens advocating for the preservation of Chicago’s historic architecture Preservation Chicago Citizens advocating for theJune preservation 9, 2011 of Chicago’s historic architecture Andrew Mooney Commissioner, Department of Housing and Economic Development City Hall – 121 N. LaSalle, 10th Floor JanuaryChicago, 04, 2018IL 60602 Brad Suster June 9, 2011 PresidentPresident Re: Support for St. Boniface church adaptive reuse plan Ward Miller* Ms. EleanorAndrew Gorski, Mooney Deputy Commissioner, Department of Planning and Development,Dear Commissioner Historic Mooney, Preservation Division JacobVice KaplanPresident Commissioner, Department of Housing and Economic Development Jack Spicer* Vice President Mr.I Johnam Citywriting Sadler, Hall in supportChicago– 121 ofN. Departmentthe LaSalle, proposed 10th adaptiveof Transportation Floor reuse plan for the former St. Boniface Church, Secretary locatedChicago, at 1328 W.IL Chestnut60602 and 921 N. Noble, presented to us by IMP Development earlier this ! Debbie Dodge* Ms.week. Abby TheMonroe, latest proposalCoordinating incorporates Planner the, adaptiveDepartment reuse ofof anPlanning existing andhistoric structure coupled Development DebbieTreasurer Dodge with new construction. PresidentGreg Brewer* Re: Support for St. Boniface church adaptive reuse plan SecretaryWard Miller* City of Chicago Board of Directors Efforts to preserve and repurpose this important neighborhood structure date to 1998 and Preservation ! Beth Baxter 121 N. LaSalleDear Commissioner Street Mooney, -

The Life and Work of Frank Lloyd Wright

THE LIFE AND WORK OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT PART 4 Ages 42 (1909) to 47 (1914) In Italy and Wisconsin Wunderlich PhD website: http://users.etown.edu/w/wunderjt/ Architecture Portfolio 8/28/2018 PART 1: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 0-19 (1867-1886) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube Context: Post Civil War recession. Industrial Revolution. Farm life. Preacher/Musician-Father, Teacher-Mother. Mother’s large influential Unitarian family of Welsh farmers. Nature. Parent’s divorce. Architecture: Froebel schooling (e.g., blocks). Barns/farm-houses (PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube). Organic Architecture roots. PART 2: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 20-33 (1887-1900) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube. Context: Rebuilding Chicago after the Great Fire. Wife Catherine and first five children. Architecture: Architects Joseph Silsbee and Louis Sullivan. Oak Park. Home & Studio. “Organic Architecture” begins. PART 3: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 34-41 (1901-1908) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube. Context: First Japan trip (PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube). Arts & Crafts movements. Six children. Architecture: Prairie Style. Oak Park & River Forest, Unity Temple, Robie House, Larkin Building. PART 4: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 42-47 (1909-1914) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube THIS LECTURE Context: Runs off with Mistress. Lives in Italy (Page MP4 YouTube). Builds Taliesin on family farmland. Mistress murdered. Architecture: Wasmuth Portfolio published(Germany).Taliesin. Many operable windows for health & passive cooling. Sculptures. PART 5: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 48-62 (1915-1929) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube Context: WWI, Roaring 20’s. Short 2nd marriage. Lives 3 yrs in Japan, then California and Wisconsin. -

Oak Park Area Visitor Guide

OAK PARK AREA VISITOR GUIDE COMMUNITIES Bellwood Berkeley Broadview Brookfield Elmwood Park Forest Park Franklin Park Hillside Maywood Melrose Park Northlake North Riverside Oak Park River Forest River Grove Riverside Schiller Park Westchester www.visitoakpark.comvisitoakpark.com | 1 OAK PARK AREA VISITORS GUIDE Table of Contents WELCOME TO THE OAK PARK AREA ..................................... 4 COMMUNITIES ....................................................................... 6 5 WAYS TO EXPERIENCE THE OAK PARK AREA ..................... 8 BEST BETS FOR EVERY SEASON ........................................... 13 OAK PARK’S BUSINESS DISTRICTS ........................................ 15 ATTRACTIONS ...................................................................... 16 ACCOMMODATIONS ............................................................ 20 EATING & DRINKING ............................................................ 22 SHOPPING ............................................................................ 34 ARTS & CULTURE .................................................................. 36 EVENT SPACES & FACILITIES ................................................ 39 LOCAL RESOURCES .............................................................. 41 TRANSPORTATION ............................................................... 46 ADVERTISER INDEX .............................................................. 47 SPRING/SUMMER 2018 EDITION Compiled & Edited By: Kevin Kilbride & Valerie Revelle Medina Visit Oak Park -

Daniel H. Burnham and Chicago's Parks

Daniel H. Burnham and Chicago’s Parks by Julia S. Bachrach, Chicago Park District Historian In 1909, Daniel H. Burnham (1846 – 1912) and Edward Bennett published the Plan of Chicago, a seminal work that had a major impact, not only on the city of Chicago’s future development, but also to the burgeoning field of urban planning. Today, govern- ment agencies, institutions, universities, non-profit organizations and private firms throughout the region are coming together 100 years later under the auspices of the Burnham Plan Centennial to educate and inspire people throughout the region. Chicago will look to build upon the successes of the Plan and act boldly to shape the future of Chicago and the surrounding areas. Begin- ning in the late 1870s, Burnham began making important contri- butions to Chicago’s parks, and much of his park work served as the genesis of the Plan of Chicago. The following essay provides Daniel Hudson Burnham from a painting a detailed overview of this fascinating topic. by Zorn , 1899, (CM). Early Years Born in Henderson, New York in 1846, Daniel Hudson Burnham moved to Chi- cago with his parents and six siblings in the 1850s. His father, Edwin Burnham, found success in the wholesale drug busi- ness and was appointed presidet of the Chicago Mercantile Association in 1865. After Burnham attended public schools in Chicago, his parents sent him to a college preparatory school in New England. He failed to be accepted by either Harvard or Yale universities, however; and returned Plan for Lake Shore from Chicago Ave. on the north to Jackson Park on the South , 1909, (POC).