The Effect of the Designated Hitter Rule on Hit Batsmen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defense of Baseball

In#Defense#of#Baseball# ! ! On!Thursday!afternoon,!May!21,!Madison!Bumgarner!of!the!Giants!and! Clayton!Kershaw!of!the!Dodgers,!arguably!the!two!premiere!left@handers!in!the! National!League,!faCed!off!in!San!FranCisCo.!The!first!run!of!the!game!Came!in!the! Giants’!third,!when!Bumgarner!led!off!with!a!line!drive!home!run!into!the!left@field! bleaChers.!It!was!Bumgarner’s!seventh!Career!home!run,!and!the!first!Kershaw!had! ever!surrendered!to!another!pitCher.!In!the!top!of!the!fourth,!Kershaw!Came!to!bat! with!two!on!and!two!out.!Bumgarner!obliged!him!with!a!fastball!on!a!2@1!count,!and! Kershaw!lifted!a!fairly!deep,!but!harmless,!fly!ball!to!Center!field.!The!Giants!went!on! to!win,!4@0.!Even!though!the!pitChing!matChup!was!the!main!point!of!interest!in!the! game,!the!result!really!turned!on!that!exchange!of!at@bats.!Kershaw!couldn’t!do!to! Bumgarner!what!Bumgarner!had!done!to!him.! ! ! A!week!later,!the!Atlanta!Braves!were!in!San!FranCisCo,!and!the!Giants!sent! rookie!Chris!Heston!to!the!mound,!against!the!Braves’!Shelby!Miller.!Heston!and! Miller!were!even!better!than!Bumgarner!and!Kershaw!had!been,!and!the!game! remained!sCoreless!until!Brandon!Belt!reaChed!Miller!for!a!solo!home!run!in!the! seventh.!Miller!was!due!to!bat!seCond!in!the!eighth!inning,!and!with!the!Braves! behind!with!only!six!outs!remaining,!manager!Fredi!Gonzalez!elected!to!pinch@hit,! even!though!Miller!had!only!thrown!86!pitches.!The!Braves!failed!to!score,!and!with! the!Braves’!starter!out!of!the!game,!the!Giants!steamrolled!the!Braves’!bullpen!for! six!runs!in!the!bottom!of!the!eighth.!They!won!by!that!7@0!score.! -

Base Umpire Field Positioning

Base Umpire Field Positioning Responsibilities: Field Diagrams with Umpires ‐‐ small diamond base paths A position ‐‐ Base umpire will: •Watch for illegal pitches •Make the safe/out call at 1st •Be responsible for fail/foul calls from the bag and beyond Position of Base Umpire when Batter is up •If the batter‐runner gets a base hit that goes through the infield the base umpire will take the batter‐runner around the bases watching the batter‐runner touch bases and A position ‐‐ with no runners on base make any calls at the bases. B position ‐‐ with only a runner on 1st base B and C position –Base umpire will: • Be responsible for any pick off plays at any of the bases C position – all other runner combinations • Illegal pitches • Make calls on the bases unless the plate umpire is covering third base on certain Note: all positions are before each pitch – situations move accordingly during each play. • Be responsible for runners touching bases during a base hit and fly balls. Plate Umpire Movement will depend on where the ball is hit. • After the ball is hit the base umpire needs to move into different positions depending Range and Working Area of Base Umpire on the play. When moving into position, remember “Inside/Outside.” If the ball is in the infield, the base umpire will generally be outside the baseline. If the ball is hit to the outfield, you should move to the infield side of the baseline. = movement of position • Batted balls that stay in the infield, stay outside and cover 1st and 2nd base. -

Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter De Rosa Bridgewater State College

Bridgewater Review Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 7 Jun-2004 Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter de Rosa Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation de Rosa, Peter (2004). Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918. Bridgewater Review, 23(1), 11-14. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol23/iss1/7 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Boston Baseball Dynasties 1872–1918 by Peter de Rosa It is one of New England’s most sacred traditions: the ers. Wright moved the Red Stockings to Boston and obligatory autumn collapse of the Boston Red Sox and built the South End Grounds, located at what is now the subsequent calming of Calvinist impulses trembling the Ruggles T stop. This established the present day at the brief prospect of baseball joy. The Red Sox lose, Braves as baseball’s oldest continuing franchise. Besides and all is right in the universe. It was not always like Wright, the team included brother George at shortstop, this. Boston dominated the baseball world in its early pitcher Al Spalding, later of sporting goods fame, and days, winning championships in five leagues and build- Jim O’Rourke at third. ing three different dynasties. Besides having talent, the Red Stockings employed innovative fielding and batting tactics to dominate the new league, winning four pennants with a 205-50 DYNASTY I: THE 1870s record in 1872-1875. Boston wrecked the league’s com- Early baseball evolved from rounders and similar English petitive balance, and Wright did not help matters by games brought to the New World by English colonists. -

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

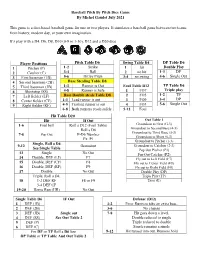

Baseball Pitch by Pitch Dice Game Instruction

Baseball Pitch By Pitch Dice Game By Michel Gaudet July 2021 This game is a dice-based baseball game for one or two players. It simulates a baseball game between two teams from history, modern day, or your own imagination. It’s play with a D4. D6, D8, D10 (0-9 or 1-10), D12 and a D20 dice. Player Positions Pitch Table D6 Swing Table D4 DP Table D6 1 Pitcher (P) 1-2 Strike 1 hit Double Play 2 Catcher (C) 3-4 Ball 2 no hit 1-3 DP 3 First baseman (1B) 5-6 Hit by Pitch 3-4 no swing 4-6 Single Out 4 Second baseman (2B) Base Stealing Table D8 5 Third baseman (3B) 1-3 Runner is Out Foul Table D12 TP Table D6 6 Shortstop (SS) 4-8 Runner is Safe 1 FO7 Triple play 7 Left fielder (LF) Base Double steals Table D8 2 FO5 1-2 TP 8 Center fielder (CF) 1-3 Lead runner is out 3 FO9 3-4 DP 9 Right fielder (RF) 4-5 Trailing runner is out 4 FO3 5-6 Single Out 6-8 Both runners reach safely 5-12 Foul Hit Table D20 Hit If Out Out Table 1 1-6 Foul ball Roll a D12 (Foul Table) Groundout to First (G-3) Roll a D6 Groundout to Second Base (4-3) Groundout to Third Base (5-3) 7-8 Pop Out P-D6 Number Groundout to Short (6-3) Ex. P1 Groundout to Pitcher (1-3) Single, Roll a D6 9-12 Groundout Groundout to Catcher (2-3) See Single Table Pop Out Pitcher (P1) 13 Single No Out Pop Out Catcher (P2) 14 Double, DEF (LF) F7 Fly out to Left Field (F7) 15 Double, DEF (CF) F8 Fly out to Center Field (F8) 16 Double, DEF (RF) F9 Fly out to Right Field (F9) 17 Double No Out Double Play (DP) Triple, Roll a D4, Triple Play (TP) 18 1-2 DEF RF F8 or F9 Error (E) 3-4 DEF CF 19-20 Home Run (HR) No Out Single Table D6 IF Out Defense (D12) 1 DEF (1B) 1-2 Error Runners take an extra base. -

BSITH Los Angeles Angels Offical Rules.Docx

Best Seats in the House at Angel Stadium Sweepstakes The following terms, conditions and rules ("Official Rules") explain and govern the "Best Seats in the House at Angel Stadium Sweepstakes" ("Sweepstakes") as presented and sponsored by Jerome’s Furniture Warehouse, 16960 Mesamint St., CA 92127 (“Jerome’s” or “Contest Administrator”), with permission from Angels Baseball LP (“ABLP”) regarding Prizes being offered. NO PURCHASE OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN THIS SWEEPSTAKES. A PURCHASE WILL NOT IMPROVE YOUR CHANCE OF WINNING. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED OR RESTRICTED BY LAW. SWEEPSTAKES PERIOD: The Sweepstakes begins on March 23, 2021, and ends on September 2, 2021 (“Sweepstakes Period”). The Sweepstakes Period will consist of (12) “Entry Periods" as set forth in the chart below: Entry Period Home Game Start Date End Date Designated Drawing Date Date (on or about) 1 4/1/2021 3/23/2021 3/25/2021 3/26/2021 1 4/2/2021 3/23/2021 3/25/2021 3/26/2021 1 4/3/2021 3/23/2021 3/25/2021 3/26/2021 1 4/4/2021 3/23/2021 3/25/2021 3/26/2021 1 4/5/2021 3/23/2021 3/25/2021 3/26/2021 1 4/6/2021 3/23/2021 3/25/2021 3/26/2021 2 4/16/2021 3/26/2021 4/1/2021 4/2/2021 2 4/17/2021 3/26/2021 4/1/2021 4/2/2021 2 4/18/2021 3/26/2021 4/1/2021 4/2/2021 2 4/19/2021 3/26/2021 4/1/2021 4/2/2021 2 4/20/2021 3/26/2021 4/1/2021 4/2/2021 2 4/21/2021 3/26/2021 4/1/2021 4/2/2021 3 5/3/2021 4/2/2021 4/18/2021 4/19/2021 3 5/4/2021 4/2/2021 4/18/2021 4/19/2021 3 5/5/2021 4/2/2021 4/18/2021 4/19/2021 3 5/6/2021 4/2/2021 4/18/2021 4/19/2021 3 5/7/2021 4/2/2021 4/18/2021 4/19/2021 -

Oakland Athletics Baseball Company7000 Coliseum Wayoakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900 PR on Twitter @Asmedia Alerts OAKLAND ATHLETICS (11-17-3) VS

O AKLAND A THLETICS Game Information Oakland Athletics Baseball Company7000 Coliseum WayOakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900www.athletics.comA’s PR on Twitter @AsMedia Alerts OAKLAND ATHLETICS (11-17-3) VS. SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (13-19-1) SATURDAY, APRIL 2, 2016 – OAKLAND ALAMEDA COUNTY COLISEUM – 1:05 P.M. PST CSNCA – A’S RADIO NETWORK (95.7 FM THE GAME) ABOUT THE A’S: Have lost five straight and eight of the last nine games… for the lead in runs (11)…has appeared in 14 games in left field and three this is the A’s longest Spring Training losing streak since dropping the final in right field…Jed Lowrie is 7-for-18 (.389) over his last seven games six games of 2011…are 11-17-3, which is the third worst record among and is batting .395 overall…nine of his last 12 hits are for extra bases Cactus League teams (San Diego, 10-20-2; Chicago-NL, 11-18-2)…will (seven doubles, one triple, one home run)…leads the A’s and is tied for finish with a losing record for the first time since 2011 when they went fifth in the CL in doubles (7)…is tied for the team lead in slugging (.674)… 12-21-1…the A’s have committed 44 errors, which is seven more than any has appeared in 15 games at second base and two at shortstop…Bruce other team (37, Chicago-NL)…the errors are the most by an A’s team dur- Maxwell (NR) is 2-for-11 (.182) with a home run and two RBI in 10 games ing the spring since the 2002 club also had 44…the A’s pitching staff is tied since returning from playing for Germany in the World Baseball Classic with Boston for the most walks (123)…have matched -

Time to Drop the Infield Fly Rule and End a Common Law Anomaly

A STEP ASIDE TIME TO DROP THE INFIELD FLY RULE AND END A COMMON LAW ANOMALY ANDREW J. GUILFORD & JOEL MALLORD† I1 begin2 with a hypothetical.3 It’s4 the seventh game of the World Series at Wrigley Field, Mariners vs. Cubs.5 The Mariners lead one to zero in the bottom of the ninth, but the Cubs are threatening with no outs and the bases loaded. From the hopeful Chicago crowd there rises a lusty yell,6 for the team’s star batter is advancing to the bat. The pitcher throws a nasty † Andrew J. Guilford is a United States District Judge. Joel Mallord is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Law School and a law clerk to Judge Guilford. Both are Dodgers fans. The authors thank their friends and colleagues who provided valuable feedback on this piece, as well as the editors of the University of Pennsylvania Law Review for their diligent work in editing it. 1 “I is for Me, Not a hard-hitting man, But an outstanding all-time Incurable fan.” OGDEN NASH, Line-Up for Yesterday: An ABC of Baseball Immortals, reprinted in VERSUS 67, 68 (1949). Here, actually, we. See supra note †. 2 Baseball games begin with a ceremonial first pitch, often resulting in embarrassment for the honored guest. See, e.g., Andy Nesbitt, UPDATE: 50 Cent Fires back at Ridicule over His “Worst” Pitch, FOX SPORTS, http://www.foxsports.com/buzzer/story/50-cent-worst-first-pitch-new-york- mets-game-052714 [http://perma.cc/F6M3-88TY] (showing 50 Cent’s wildly inaccurate pitch and his response on Instagram, “I’m a hustler not a damn ball player. -

Basic Baseball Fundamentals Batting

Basic Baseball Fundamentals Batting Place the players in a circle with plenty of room between each player with the Command Coach in the center. Other coaches should be outside the circle observing. If someone needs additional help or correction take that individual outside the circle. When corrected have them rejoin the circle. Each player should have a bat. Batting: Stance/Knuckles/Ready/Load-up/Sqwish/Swing/Follow Thru/Release Stance: Players should be facing the instructor with their feet spread apart as wide as is comfortable, weight balanced on both feet and in a straight line with the instructor. Knuckles: Players should have the bat in both hands with the front (knocking) knuckles lined up as close as possible. Relaxed Ready: Position that the batter should be in when the pitcher is looking in for signs and is Ready to pitch. In a proper stance with the knocking knuckles lined up, hands in front of the body at armpit height and the bat resting on the shoulder. Relaxed Load-up: Position the batter takes when the pitcher starts to wind up or on the first movement after the stretch position. When the pitcher Loads-up to pitch, the batter Loads-up to hit. Shift weight to the back foot. Pivot on the front foot, which will raise the heel slightly off the ground. Hands go back and up at least to shoulder height (Hands up). By shifting the weight to the back foot, pivoting on the front foot and moving the hands back and up, it will move the batter into an attacking position. -

How to Maximize Your Baseball Practices

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the author. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ii DEDICATED TO ••• All baseball coaches and players who have an interest in teaching and learning this great game. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to\ thank the following individuals who have made significant contributions to this Playbook. Luis Brande, Bo Carter, Mark Johnson, Straton Karatassos, Pat McMahon, Charles Scoggins and David Yukelson. Along with those who have made a contribution to this Playbook, I can never forget all the coaches and players I have had the pleasure tf;> work with in my coaching career who indirectly have made the biggest contribution in providing me with the incentive tQ put this Playbook together. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS BASEBALL POLICIES AND REGULATIONS ......................................................... 1 FIRST MEETING ............................................................................... 5 PLAYER INFORMATION SHEET .................................................................. 6 CLASS SCHEDULE SHEET ...................................................................... 7 BASEBALL SIGNS ............................................................................. 8 Receiving signs from the coach . 9 Sacrifice bunt. 9 Drag bunt . 10 Squeeze bunt. 11 Fake bunt and slash . 11 Fake bunt slash hit and run . 11 Take........................................................................................ 12 Steal ....................................................................................... -

OFFICIAL GAME INFORMATION Lake County Captains (14-15) Vs

High-A Affiliate OFFICIAL GAME INFORMATION Lake County Captains (14-15) vs. Dayton Dragons (16-13) Sunday, June 6th • 1:30 p.m. • Classic Park • Broadcast: WJCU.org Game #30 • Home Game #12 • Season Series: 3-2, 19 Games Remaining RHP Mason Hickman (1-2, 3.45 ERA) vs. RHP Spencer Stockton (2-0, 3.57 ERA) YESTERDAY: The Captains’ three-game winning streak ended with a 15-4 loss to Dayton on Saturday night. Kevin Coulter surrendered seven runs on 10 hits over 1.2 innings to take the loss in a spot start. Dragons centerfielder Quin Cotton hit two home runs and drove in six High-A Central League runs to lead the Dayton offense. Dragons starter Graham Ashcraft earned the win with seven strong innings, in which he allowed just one run on two hits and struck out nine. East Division W L GB COMING ALIVE: After scoring just 12 runs and suffering a six-game sweep last week at West Michigan, the Captains have already scored 29 runs in the first five games of this series against Dayton. Will Brennan has gone 7-for-18 (.389) with two home runs, two doubles, 10 RBI and West Michigan (Detroit) 16 12 -- a 1.254 OPS. Joe Naranjo has gone 3-for-10 with a team-leading five walks for a .533 on-base percentage. Dayton (Cincinnati) 16 13 0.5 BRENNAN BASHING: Captains OF Will Brennan leads the High-A Central League (HAC) lead in doubles (11). He is second in batting average (.326), fourth in wRC+ (154), fifth in on-base percentage (.410), sixth in OPS (.920), sixth in extra-base hits (13) and ninth in slugging Great Lakes (Los Angeles - NL) 15 14 1.5 percentage (.511). -

St. Louis Amateur Baseball Association Playing Rules

ST. LOUIS AMATEUR BASEBALL ASSOCIATION PLAYING RULES 1.00 ENTRY FEE 1.01 Entry fees, covering association-operating costs, will be paid by each participating team during the year and shall be the responsibility of the head of the organization. Costs should be determined no later than the January regular meeting. 1.02 A deposit of $250.00 will be made at the January meeting by the first team in each organization. Additional teams in an organization will make deposits of $100.00. 1.03 Full payment of all fees shall be due no later than the May regular meeting with the exception of the 14 and 13 & under teams that shall be paid in March. 1.04 Entry fees shall include: affiliation fees, insurance, game balls, trophies, banquet reservations, awards, and any other fee determined by the Executive Board. 1.05 Umpire fees are not part of the entry fee; each team is required to pay one umpire directly on the field prior to the commencement of the game. Umpires are to be paid the exact contracted fee, no more and no less. 2.00 ELIGIBLE PLAYERS, TERRITORIES & RECRUITING 2.01 Eligible Players Each organization can draw players who attend any public or private high school in the immediate St. Louis metropolitan area or adjoining counties (the player’s legal residence is the address recorded at the school the player attends as of March 31 of the current year). While programs do not have exclusive rights to players from “base schools,” the spirit of this rule is that the majority of an organization’s players should be recruited from within a reasonable distance to the home field of that organization.