The Effect of Concussion on Batting Performance of Major League Baseball Players

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

Basic Baseball Fundamentals Batting

Basic Baseball Fundamentals Batting Place the players in a circle with plenty of room between each player with the Command Coach in the center. Other coaches should be outside the circle observing. If someone needs additional help or correction take that individual outside the circle. When corrected have them rejoin the circle. Each player should have a bat. Batting: Stance/Knuckles/Ready/Load-up/Sqwish/Swing/Follow Thru/Release Stance: Players should be facing the instructor with their feet spread apart as wide as is comfortable, weight balanced on both feet and in a straight line with the instructor. Knuckles: Players should have the bat in both hands with the front (knocking) knuckles lined up as close as possible. Relaxed Ready: Position that the batter should be in when the pitcher is looking in for signs and is Ready to pitch. In a proper stance with the knocking knuckles lined up, hands in front of the body at armpit height and the bat resting on the shoulder. Relaxed Load-up: Position the batter takes when the pitcher starts to wind up or on the first movement after the stretch position. When the pitcher Loads-up to pitch, the batter Loads-up to hit. Shift weight to the back foot. Pivot on the front foot, which will raise the heel slightly off the ground. Hands go back and up at least to shoulder height (Hands up). By shifting the weight to the back foot, pivoting on the front foot and moving the hands back and up, it will move the batter into an attacking position. -

OFFICIAL GAME INFORMATION Lake County Captains (14-15) Vs

High-A Affiliate OFFICIAL GAME INFORMATION Lake County Captains (14-15) vs. Dayton Dragons (16-13) Sunday, June 6th • 1:30 p.m. • Classic Park • Broadcast: WJCU.org Game #30 • Home Game #12 • Season Series: 3-2, 19 Games Remaining RHP Mason Hickman (1-2, 3.45 ERA) vs. RHP Spencer Stockton (2-0, 3.57 ERA) YESTERDAY: The Captains’ three-game winning streak ended with a 15-4 loss to Dayton on Saturday night. Kevin Coulter surrendered seven runs on 10 hits over 1.2 innings to take the loss in a spot start. Dragons centerfielder Quin Cotton hit two home runs and drove in six High-A Central League runs to lead the Dayton offense. Dragons starter Graham Ashcraft earned the win with seven strong innings, in which he allowed just one run on two hits and struck out nine. East Division W L GB COMING ALIVE: After scoring just 12 runs and suffering a six-game sweep last week at West Michigan, the Captains have already scored 29 runs in the first five games of this series against Dayton. Will Brennan has gone 7-for-18 (.389) with two home runs, two doubles, 10 RBI and West Michigan (Detroit) 16 12 -- a 1.254 OPS. Joe Naranjo has gone 3-for-10 with a team-leading five walks for a .533 on-base percentage. Dayton (Cincinnati) 16 13 0.5 BRENNAN BASHING: Captains OF Will Brennan leads the High-A Central League (HAC) lead in doubles (11). He is second in batting average (.326), fourth in wRC+ (154), fifth in on-base percentage (.410), sixth in OPS (.920), sixth in extra-base hits (13) and ninth in slugging Great Lakes (Los Angeles - NL) 15 14 1.5 percentage (.511). -

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics History Softball was created by George Hancock in Chicago in 1887. The game originated as an indoor variation of baseball and was eventually converted to an outdoor game. The popularity of softball has grown considerably, both at the recreational and competitive levels. In fact, not only is women’s fast pitch softball a popular high school and college sport, it was recognized as an Olympic sport in 1996. Object of the Game To score more runs than the opposing team. The team with the most runs at the end of the game wins. Offense & Defense The primary objective of the offense is to score runs and avoid outs. The primary objective of the defense is to prevent runs and create outs. Offensive strategy A run is scored every time a base runner touches all four bases, in the sequence of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and home. To score a run, a batter must hit the ball into play and then run to circle the bases, counterclockwise. On offense, each time a player is at-bat, she attempts to get on base via hit or walk. A hit occurs when she hits the ball into the field of play and reaches 1st base before the defense throws the ball to the base, or gets an extra base (2nd, 3rd, or home) before being tagged out. A walk occurs when the pitcher throws four balls. It is rare that a hitter can round all the bases during her own at-bat; therefore, her strategy is often to get “on base” and advance during the next at-bat. -

NFHS NEW DESIGNATED HITTER RULE 2020 Player May Be Listed As Both the Fielder and the DH

NFHS NEW DESIGNATED HITTER RULE 2020 Player may be listed as both the fielder and the DH. Player may be substituted for defensively and still be the DH. Once the DH is substituted for on offense, the role of DH is extinguished for the game and only one player may occupy that spot in the batting order. If the pitcher or catcher are listed as P/DH or C/DH they are NOT allowed courtesy runners. The player listed in the starting lineup as fielder/DH may come out of the game in either role and re-enter once. Sanders is listed as the P/DH, hitting in the third position in the batting order. In the fifth inning, McNeely enters the game as pitcher with Sanders reaching his pitch count limit. Sanders continues as DH for McNeely. Ruling: Legal 3. Sanders P /DH McNeely (5) P In the 6th inning, substitute Jackson enters to pitch replacing McNeely. Sanders remains the DH for Sanders. Ruling:Legal 3. Sanders P /DH McNeely (5) P Jackson (6) P In the 7th inning, Sanders returns to defense as the catcher and is still listed as the DH. Ruling: Legal Sanders was a starter and is eligible to re-enter the game once. 3. Sanders P /DH/C McNeely (5) P Jackson (6) P With Dolan listed in the starting lineup as the 2B/DH and batting 4th in the order, the coach wants to bring in Tatelman to hit for Dolan. Ruling: If substitute Tatelman comes in to hit (or run) for Dolan, the role of the DH is terminated for the game. -

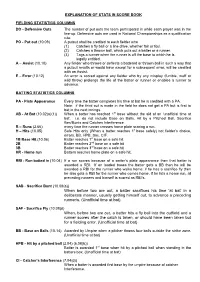

How to Do Stats

EXPLANATION OF STATS IN SCORE BOOK FIELDING STATISTICS COLUMNS DO - Defensive Outs The number of put outs the team participated in while each player was in the line-up. Defensive outs are used in National Championships as a qualification rule. PO - Put out (10.09) A putout shall be credited to each fielder who (1) Catches a fly ball or a line drive, whether fair or foul. (2) Catches a thrown ball, which puts out a batter or a runner. (3) Tags a runner when the runner is off the base to which he is legally entitled. A – Assist (10.10) Any fielder who throws or deflects a battered or thrown ball in such a way that a putout results or would have except for a subsequent error, will be credited with an Assist. E – Error (10.12) An error is scored against any fielder who by any misplay (fumble, muff or wild throw) prolongs the life of the batter or runner or enables a runner to advance. BATTING STATISTICS COLUMNS PA - Plate Appearance Every time the batter completes his time at bat he is credited with a PA. Note: if the third out is made in the field he does not get a PA but is first to bat in the next innings. AB - At Bat (10.02(a)(1)) When a batter has reached 1st base without the aid of an ‘unofficial time at bat’. i.e. do not include Base on Balls, Hit by a Pitched Ball, Sacrifice flies/Bunts and Catches Interference. R – Runs (2.66) every time the runner crosses home plate scoring a run. -

Softball Skills — Pepper, Umpiring, Infield Practice, Batting Practice

GRADES 3-4 LESSON FOCUS Softball Skills — Pepper, Umpiring, Infield Practice, Batting Practice SHAPE Standards: DPE Outcomes: Equipment: 1, 4 • I can catch a rolled softball demonstrating three of • Whiffle balls four cues. • Plastic bats for whiffle balls • I can strike a ball using a bat demonstrating two of • Batting tee four cues. • Bases • I can work safely in a small group. • Soccer ball Instructions Skills Review skills previously learned: 1. Overhand Throw 2. Pitching 3. Fielding Grounders 4. Batting Station (Small-Group) Instruction Station 1 — Play Pepper (Hitting and Fielding) A line of 3-4 players is about 10 yards in front of and facing a batter. The players toss the ball to the batter, who attempts to hit controlled grounders back to them. The batter stays at bat for a period of time and then rotates to the field. Station 2 — Pitching and Umpiring Students find a partner and pitch and catch with each other. Set out a number of bases at each station so pitchers can pitch and catch using a base as a target (home plate). a. Pitch to another player over a plate. b. Call balls and strikes. One player is the pitcher, the second is the catcher, and the third is the umpire. A fourth player can be a stationary batter to provide a more realistic pitching target. Station 3 — Infield Practice 1. Throw around the bases clockwise and counterclockwise. 1 of 2 GRADES 3-4 LESSON FOCUS Softball Skills — Pepper, Umpiring, Infield Practice, Batting Practice 2. Roll ball to infielders and make the play at first. -

Leveraging Pitcher-Batter Matchups for Optimal Game Strategy

Leveraging Pitcher-Batter Matchups for Optimal Game Strategy Paper Track: Baseball Paper ID: 13603 Willie K. Harrison∗ and John L. Salmony ∗Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, Brigham Young University yDepartment of Mechanical Engineering, Brigham Young University 1. Introduction Recent play in Major League Baseball (MLB) has showcased many attempts to achieve an advantage through smart selection of pitcher-batter matchups. One such case in the 2018 postseason had the Los Angeles Dodgers’ manager, Dave Roberts, selecting an all right-handed batting lineup to face both Chris Sale and David Price in games one and two of the World Series. Both pitchers are left-handed, and the choice certainly tailors to the well-known lefty-righty handedness matchup strategy [10]. Further- more, this choice was inline with the platoon system that the Dodgers had employed throughout the 2018 regular season [15], often starting all right-handed batting lineups against left-handed starters, seemingly with great success. Although attempts have been made to optimize pitcher-batter matchup strategies in the sabermet- rics [2, 7, 9] literature (e.g., [5, 6]), these approaches have tended to apply averages of large data sets in an attempt to ��ine tune some matchup data. For example, Hirotsu and Wright used the handedness (i.e., left handed or right handed) of both the pitcher and the batter to adjust average batting statistics in an attempt to optimize the choice of pitcher substitution [6]. In this approach, if a batter’s dominant hand is opposite to that of a pitcher’s dominant hand, then the offensive statistics of the batter are as- sumed to be enhanced slightly for that speciic matchup. -

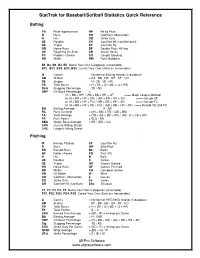

Stattrak for Baseball/Softball Statistics Quick Reference

StatTrak for Baseball/Softball Statistics Quick Reference Batting PA Plate Appearances HP Hit by Pitch R Runs CO Catcher's Obstruction H Hits SO Strike Outs 2B Doubles SH Sacrifice Hit (sacrifice bunt) 3B Triples SF Sacrifice Fly HR Home Runs DP Double Plays Hit Into OE Reaching On-Error SB Stolen Bases FC Fielder’s Choice CS Caught Stealing BB Walks RBI Runs Batted In B1, B2, B3, B4, B5 Name Your Own Categories (renamable) BS1, BS2, BS3, BS4, BS5 Create Your Own Statistics (renamable) G Games = Number of Batting records in database AB At Bats = PA - BB - HP - SH - SF - CO 1B Singles = H - 2B - 3B - HR TB Total Bases = H + 2B + (2 x 3B) + (3 x HR) SLG Slugging Percentage = TB / AB OBP On-Base Percentage = (H + BB + HP) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Major League Method or (H + BB + HP + OE) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include OE or (H + BB + HP + FC) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include FC or (H + BB + HP + OE + FC) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include OE and FC BA Batting Average = H / AB RC Runs Created = ((H + BB) x TB) / (AB + BB) TA Total Average = (TB + SB + BB + HP) / (AB - H + CS + DP) PP Pure Power = SLG - BA SBA Stolen Base Average = SB / (SB + CS) CHS Current Hitting Streak LHS Longest Hitting Streak Pitching IP Innings Pitched SF Sacrifice Fly R Runs WP Wild Pitch ER Earned-Runs Bk Balks BF Batters Faced PO Pick Offs H Hits B Balls 2B Doubles S Strikes 3B Triples GS Games Started HR Home Runs GF Games Finished BB Walks CG Complete Games HB Hit Batter W Wins CO Catcher's Obstruction L Losses SO Strike Outs Sv Saves SH Sacrifice Hit -

Winning 12U Batting Order Strategy

Winning 12U Batting Order Strategy The goal in developing a winning 12U batting order is figuring out how to score 10 runs. Our motto in 12U was “10 to Win”. The game changes so dramatically from 10U to 12U. It goes from being a pitcher dominated game to a hitter dominated game. The pitchers have moved back from 35’ to 40’ plus they have gone to the bigger ball. Strikeouts will diminish greatly in 12U. Another big change from 10U to 12U is the importance of momentum. Momentum is HUGE in 12U. In particular, you will find this true with 7th graders more so than 6th graders. Once a 7th grader gets down, they will marginalize their effort in order to marginalize the loss. In other words, they won’t try as hard so in their mind they can think, “we lost but I didn’t try my hardest”. Good luck in your battle against that mindset with your own team. However, understanding this mindset signals how critical it is to score in the first inning. So our goals in setting the 12U lineup are twofold. First, score in the first inning and second, score 10 runs. If you accomplish the first goal, the second goal is much easier due to momentum. 1) Leadoff Hitter – Must have a high on base percentage and great speed. We need the player on base and have the ability to steal 2B and possibly 3B. 2) If you have a great leadoff hitter, I like to put a bunter in this spot. If my leadoff hitter is on 1B, I’m “taking” the first pitch to allow my runner to steal 2B. -

19 Caitlin Benyi Senior • 2B • 5-8 • Bats: R • Throws: R • Scottsdale, Az • Horizon Hs

PDuisLAYER nibh ex B exerIOGRAPHIES si bla at acil iril etum zzril ex el in ver illaore #19 CAITLIN BENYI SENIOR • 2B • 5-8 • BATS: R • THROWS: R • SCOTTSDALE, AZ • HORIZON HS Enquist on Benyi USA Softball (2004) Caitlin is an integral part of what Played in 17 of a possible 18 games with the USA Schutt Elite we will accomplish this season. Team at the Canada Cup and Champions Cup … Hit .314 for the Her consistency and leadership tour with a double and a triple … Played in all nine games for USA makes her an important leader Elite at the World University Games in October … Team won gold on this team. … Scored three runs with three RBI and a double. 2005 Honors/Awards 2004 Honors/Awards Second-Team NFCA All-America First-Team All-America at second base … First-Team All-Pacifi c at second base … UCLABruins. Region at second base … First-Team Easton All-America … First- com/MetRX, USA Softball and Team All-Pac-10 … NCAA Division I Home Run Champion (24 Pac-10 Player of the Week for HR, 0.43/game) … All-tournament at the Women’s College World Week ending May 8 … First-Team Series … Unanimous selection to the NCAA Regional All-Tourna- All-Pac-10 … First-Team All-Pa- ment Team … Pac-10 Player of the Week for Apr. 19 and May 11 cifi c Region at 2B … NFCA National Player of the Week for May 12. 2005 (Junior) 2004 (Sophomore) Perfect on 28 defensive chances at the Women’s College World Started UCLA’s last 22 games at second base after splitting time Series … Homered in the second game of the Championship between 2B and RF previously … Entered the -

Height, Weight, and Durability in Major League Baseball Joshua Yeager Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2017 Height, Weight, and Durability in Major League Baseball Joshua Yeager Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Yeager, Joshua, "Height, Weight, and Durability in Major League Baseball" (2017). CMC Senior Theses. 1684. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1684 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College HEIGHT, WEIGHT AND DURABILITY IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR HEATHER ANTECOL BY JOSHUA YEAGER FOR SENIOR THESIS SPRING 2017 APRIL 24th, 2017 Yeager 1 Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ 3 I. Introduction.......................................................................................................................................... 4 II. Literature Review ............................................................................................................................ 6 III. Data ..................................................................................................................................................