Guidelines for Primary Mental Health Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi 2 Turkish Journal of Psychiatry

2 Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi 2 Turkish Journal of Psychiatry CİLT | Volume 27 GÜZ | Autumn 2016 EK | Supplement 2: 52. ULUSAL PSİKİYATRİ KONGRESİ TÜRKİYE SİNİR VE ABSTRACTS RUH SAĞLIĞI ISSN 1300 – 2163 DERNEĞİ 2 Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi 2 Mart, Haziran, Eylül ve Aralık aylarında olmak üzere yılda 4 sayı çıkar Turkish Journal of Psychiatry Four issues annually: March, June, September, December CİLT | Volume 27 GÜZ | Autumn 2016 Türkiye Sinir ve Ruh Sağlığı Derneği EK | Supplement 2 tarafından yayınlanmaktadır. ISSN 1300 – 2163 www.turkpsikiyatri.com Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi Bu Sayının Yayın Yönetmeni /Editor in Chief of this Issue Doç. Dr. Semra Ulusoy Kaymak Türkiye Sinir ve Ruh Sağlığı Derneği adına Sahibi ve Sorumlu Müdürü Kongre Başkanları Published by Turkish Association of Nervous and Mental Health Prof. Dr. M. Orhan Öztürk E. Timuçin Oral - Ekrem Cüneyt Evren Düzenleme Kurulu Yayın Yönetmeni/ Editor in Chief Ekrem Cüneyt Evren (Başkan) Prof. Dr. Aygün Ertuğrul Ercan Dalbudak Selim Tümkaya Yazışma Adresi / Corresponding Address Semra Ulusoy Kaymak PK 401, Yenişehir 06442 Ankara Sinan Aydın (Genç Üye) Yönetim Yeri / Editorial Office Bu Sayının Yayın Yönetmen Yardımcıları Kenedi Cad. 98/4, Kavaklıdere, Ankara / Assoc. Editors in Chief of this Issue Telefon: (0-312) 427 78 22 Faks: (0-312) 427 78 02 Sinan Aydın Esra Kabadayı Yayın Türü / Publication Category Selim Tümkaya Yaygın, Süreli, Bilimsel Yayın Yayın Hizmetleri / Publishing Services BAYT Bilimsel Araştırmalar Reklam / Advertisements Basın Yayın ve Tanıtım Ltd. Şti. Reklam koşulları ve diğer ayrıntılar için yayın yönetmeniyle Tel (0-312) 431 30 62, Faks: (0-312) 431 36 02 ilişkiye geçilmesi gerekmektedir. E-posta: [email protected] (Dergide yer alan yazılarda belirtilen görüşlerden yazarlar sorumludur. -

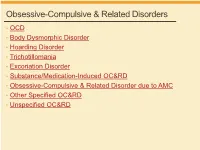

Obsessive-Compulsive & Related Disorders

Obsessive-Compulsive & Related Disorders • OCD • Body Dysmorphic Disorder • Hoarding Disorder • Trichotillomania • Excoriation Disorder • Substance/Medication-Induced OC&RD • Obsessive-Compulsive & Related Disorder due to AMC • Other Specified OC&RD • Unspecified OC&RD B Chow 2019 OCD OCD – Diagnostic Criteria A. Obsessions, compulsions, or both: 1. Obsessions (2/2) • Recurrent thoughts/urges/images, intrusive + unwanted, distressing • Attempts to supress, ignore or neutralize 2. Compulsions (2/2) • Repetitive behaviors, feels driven to do, due to obsession or rules • Aimed to prevent anxiety/distress, but not connected or excessive B. Time-consuming, or sig distress/impairment C. Not due to substance or AMC D. Not better explained by AMD DSM5 OCD – Diagnostic Specifiers • Specify if: • With good or fair insight: recognizes definitely/probably not true • With poor insight: thinks probably true • With absent insight/delusional beliefs: convinced beliefs are true • Specify if: • Tic-related: current OR past hx of tic disorder DSM5 OCD – Diagnostic Specifiers • Dysfunctional beliefs • Inflated sense of responsibility, tendency to overestimate threat • Perfectionism, intolerance of uncertainty • Over-importance of thoughts, need to control thoughts • Degree of insight → accuracy of beliefs, can vary over course • Good/fair insight → many • Poor insight → some • Absent insight/delusional beliefs → 4% or less • Poorer insight → worse long-term outcome • Tic disorders → 30% of OCD have lifetime tic disorder • Most common in MALES with childhood-onset -

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy of Obsessive- Compulsive Disorder

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Veterinary medicine - Repository of PHD, master's thesis UNIVERSITY OF ZAGREB SCHOOL OF MEDICINE Veronika Nives Zoric Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy of Obsessive- Compulsive Disorder GRADUATE THESIS Zagreb, 2017. This graduate thesis was made at the Department of Psychiatry KBC Zagreb, University of Zagreb School of Medicine, mentored by prof. dr. sc. Dražen Begić and was submitted for evaluation in the 2016/2017 academic year. Mentor: prof. dr. sc. Dražen Begić ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE TEXT: Behaviour Therapy (BT) Bibliotherapy administered CBT (bCBT) Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT) Cognitive Therapy (CT) Computerized CBT (cCBT) Danger Ideation Reduction Therapy (DIRT) Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) Internet-administered CBT (iCBT) Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAO) Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD) Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) Serotonin; 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT) Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SRI) Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) Telephone administered CBT (tCBT) Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCA) Videoconferencing administered CBT (vCBT) Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY 2. SAŽETAK 3. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ -

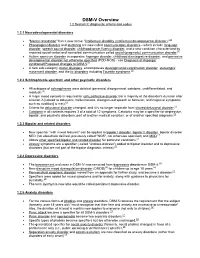

DSM-V Overview 1.2 Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes

DSM-V Overview 1.2 Section II: diagnostic criteria and codes 1.2.1 Neurodevelopmental disorders "Mental retardation" has a new name: "intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder)."[4] Phonological disorder and stuttering are now called communication disorders—which include language disorder, speech sound disorder, childhood-onset fluency disorder, and a new condition characterized by impaired social verbal and nonverbal communication called social (pragmatic) communication disorder.[4] Autism spectrum disorder incorporates Asperger disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) - see Diagnosis of Asperger syndrome#Proposed changes to DSM-5.[5] A new sub-category, motor disorders, encompasses developmental coordination disorder, stereotypic movement disorder, and the tic disorders including Tourette syndrome.[6] 1.2.2 Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders All subtypes of schizophrenia were deleted (paranoid, disorganized, catatonic, undifferentiated, and residual).[2] A major mood episode is required for schizoaffective disorder (for a majority of the disorder's duration after criterion A [related to delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech or behavior, and negative symptoms such as avolition] is met).[2] Criteria for delusional disorder changed, and it is no longer separate from shared delusional disorder.[2] Catatonia in all contexts requires 3 of a total of 12 symptoms. Catatonia may be a specifier for depressive, bipolar, -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the Editor Letters to the Editor © Copyright 1998 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc. Possible Risks Associated With 3. Witvrouw M, Schmit JC, Van Remoortel B, et al. Cell type-dependent Valproate Treatment of AIDS-Related Mania effect of sodium valproate on human immunodeficiency type 1 repli- cation in vitro. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1997;13:187–192 4. Kuntz-Simon G, Obert G. Sodium valproate, an anticonvulsant drug, Sir: Recently, RachBeisel and Weintraub contributed further stimulates human cytomegalovirus replication. J Gen Virol 1995;76: to the literature on the usefulness of valproate for treating 1409–1415 AIDS-related mania.1 Contrary to current trends, they appar- ently prescribed valproic acid rather than divalproex sodium— James W. Jefferson, M.D. the former being less expensive, but generally less well Middleton, Wisconsin tolerated. Given the likelihood of preexisting gastrointestinal symptoms in this population, better tolerability rather than lower cost might make divalproex sodium the preferred prepa- Attacks of Jealousy ration. One personal copy may be printed That Responded to Clomipramine The authors suggest the need for further study of the use of valproate in patients with AIDS because of uncommon reports of thrombocytopenia, hepatic dysfunction, and pancreatitis as- Sir: Pathologic jealousy can be a manifestation of several sociated with the drug. They did not mention a further cause for psychiatric disorders. The patient described here suffered from concern, namely, that in vitro studies have found that valproate an atypical form of obsessive-compulsive disorder, had a strong stimulates HIV-1 virus replication2,3 and cytomegalovirus repli- family history of emotional disturbance and relationship diffi- cation.4 Were this to happen in AIDS patients, the course of the culties, and responded dramatically to treatment with low-dose illness could be altered unfavorably. -

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

PRIMER Obsessive–compulsive disorder Dan J. Stein1*, Daniel L. C. Costa2, Christine Lochner3, Euripedes C. Miguel2, Y. C. Janardhan Reddy4, Roseli G. Shavitt2, Odile A. van den Heuvel5,6 and H. Blair Simpson7 Abstract | Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a highly prevalent and chronic condition that is associated with substantial global disability. OCD is the key example of the ‘obsessive– compulsive and related disorders’, a group of conditions which are now classified together in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, and the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision, and which are often underdiagnosed and undertreated. In addition, OCD is an important example of a neuropsychiatric disorder in which rigorous research on phenomenology , psychobiology , pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy has contributed to better recognition, assessment and outcomes. Although OCD is a relatively homogenous disorder with similar symptom dimensions globally, individualized assessment of symptoms, the degree of insight, and the extent of comorbidity is needed. Several neurobiological mechanisms underlying OCD have been identified, including specific brain circuits that underpin OCD. In addition, laboratory models have demonstrated how cellular and molecular dysfunction underpins repetitive stereotyped behaviours, and the genetic architecture of OCD is increasingly understood. Effective treatments for OCD include serotonin reuptake i n h i b i t ors a n d c o g ni tive– b e h a v i o ural t h e r a py , -

DSM Part 2 Changes to Depressive Disorders

4/29/2015 DSM Part 2 Depressive Disorders through Gender Dysphoria Changes to Depressive Disorders Disruptive Mood Disregulation Disorder (new) 296.99 (F34.8) Major Depressive Disorder Severity/course Single Episode Recurrent Episode specifier Mild 296.21 (F32.0) 296.31 (F33.0) Moderate 296.22 (F32.1) 296.32 (F33.1) Severe 296.23 (F32.2) 296.33 (F33.2) With Psychotic 296.24 (F32.3) 296.34 (F33.3) Features In partial remission 296.26 (F32.4) 296.35 (F33.41) In full remission 296.26 (F32.5) 296.36 (F33.42) Unspecified 296.20 (F32.9) 296.30 (F33.9) 1 4/29/2015 Changes to Depressive Disorders Persistent Depressive Disorder (Dysthymia) 300.4 (F34.1) Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder 625.4 (N94.3) (new) Substance/Medication Induced Depressive Disorder – Codes are substance-specific and in the substance use section of DSM-5 Depressive Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition 293.83 (note additional specificity with ICD 10) With depressive features (F06.31) With major depressive-like episode (F06.32) With mixed features (F06.34) Other Specified Depressive Disorder 311 (F32.8) Unspecified Depressive Disorder 311 (F32.9) Changes to Depressive Disorders Several new disorders Disruptive Mood Dysregulation disorder (pg 156) To address concerns about over-diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in children Diagnosis for children up to 12 years who exhibit persistent irritability and frequent episodes of extreme behavioral dys-control. Not made for first time before 6 years or after 18 years Placement recognizes findings that point to these children developing unipolar depressive d/o or anxiety d/o rather than bipolar d/o as they mature (hence location in this section of DSM) It cannot coexist with Oppositional Defiant, Intermittent Explosive or bipolar disorder –but can exist with others 2 4/29/2015 Changes to Depressive Disorders Disruptive Mood Dysregulation disorder Diagnostic criteria: A. -

Curriculum Vitae Et Studiorum

CURRICULUM VITAE ET STUDIORUM ISTRUZIONE SECONDARIA 1996 Diploma di Maturità Scientifica, Liceo Scientifico Santa Caterina, Pisa ISTRUZIONE UNIVERSITARIA 2003 Laurea in Medicina e Chirurgia, Università di Pisa 110/110 e lode Tesi: “Disturbo ossessivo compulsivo farmaco resistente: efficacia e tollerabilità del potenziamento con olanzapina” 2007 Specializzazione in Psichiatria, Università di Pisa 110/110 e lode Tesi: “Clozapine treatment in psychotic patients: plasma levels and ABCB1 polymorphisms” 2008-2010 Dottorato di ricerca in “Neurobiologia e Clinica dei Disturbi Affettivi”, Università di Pisa Tesi: “Impulsivity and pathological gambling” 2009 International Master in Affective Neuroscience, Maastricht University and Università di Firenze Tesi: “Axis-I mood and anxiety comorbidity and manic spectrum symptoms in fibromyalgia: their impact on the severity of pain and the health-related quality of life” ABILITAZIONI PROFESSIONALI 2003 Abilitazione all’esercizio della professione medica, Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia, Università di Pisa ALBO PROFESSIONALE 2004 Iscrizione all’Albo dell’Ordine dei Medici Chirurghi di Pisa 2007 Iscrizione all’elenco degli psicoterapeuti dell’Ordine dei Medici di Pisa QUALIFICHE UNIVERSITARIE 2007 Vincitore di borsa di studio ministeriale associata a dottorato di ricerca in “Neurobiologia e Clinica dei Disturbi Affettivi”, Università di Pisa 2009 Cultore della materia nel settore disciplinare di “Psichiatria e Psicologia Clinica” (MED 25) nel Corso di Laurea in Medicina e Chirurgia 2011 Dottore di Ricerca -

Understanding OCD Spectrum Disorders

NURSES: Institute for Brain Potential (IBP) is accredited as a provider of nursing continuing professional development by the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s Commission on Accreditation. Institute for Brain Potential is approved as a provider of continuing education by California Board of Registered Nursing, Provider #CEP13896, Interactive Webcast and Florida Board of Nursing. This program provides 6 contact hours. PSYCHOLOGISTS: Institute for Brain Potential is approved by the American Wednesday, June 2, 2021 Psychological Association to sponsor continuing education for psychologists. Institute for Brain Potential maintains responsibility for this program and its content. This program provides 6 CE credits. Institute for Brain Potential is recognized by the New York State Education Department’s State Board for Psychology as an approved provider of continuing education for licensed psychologists #PSY-0090. IBP is approved as a provider of continuing Interactive Webcast education by the Florida Board of Psychology. This course provides 6 contact hours of CE credit. COUNSELORS, SOCIAL WORKERS & MFTs: Institute for Brain Potential has been Wednesday, June 2, 2021, 9 AM – 4 PM (PDT) approved by NBCC as an Approved Continuing Education Provider, ACEP No. 6342. Programs that do not qualify for NBCC credit are clearly identified. Institute for Brain You will need a computer with internet access and speakers or Potential is solely responsible for all aspects of the programs. This program provides 6 headphones to participate in the webcast. clock hours. Institute for Brain Potential, ACE Approval Number: 1160, is approved to offer social work continuing education by the Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB) Approved Continuing Education (ACE) program. -

Rivista Di Psichiatria | Stalking: a Neurobiological Perspective 10.03.15 16:06

Rivista di Psichiatria | Stalking: a neurobiological perspective 10.03.15 16:06 Area Abbonati Login Password Home Presentazione Comitato Scientifico Norme Editoriali Abbonamento Scarica il PDF (70,0 kb) Riv Psichiatr 2015;50(1):12-18 Rivista Stalking: a neurobiological perspective Invia un articolo Stalking: una prospettiva neurobiologica DONATELLA MARAZZITI, VALENTINA FALASCHI, AMEDEO LOMBARDI, ARCHIVIO FRANCESCO MUNGAI, LILIANA DELL’OSSO E-mail: [email protected] Numeri usciti: Dipartimento di Medicina Clinica e Sperimentale, Sezione di Psichiatria, Università di Pisa CERCA UN ARTICOLO RIASSUNTO. Lo stalking sta diventando una vera e propria emergenza sociale perché è spesso alla base di gravi comportamenti etero- e autoaggressivi. Non esistono al momento ipotesi che possano spiegare in maniera esaustiva un fenomeno così complesso, anche se le descrizioni Ricerca per titolo dettagliate di alcune sue caratteristiche permettono di formulare alcune considerazioni e proposte di lavoro. Probabilmente nello stalking sono coinvolti i sistemi che regolano il cervello sociale e la formazione della coppia, vale a dire i processi di attaccamento/separazione, Ricerca per autore attrazione/innamoramento/gratificazione. Sul piano biochimico entrerebbero in gioco un’iperattività del sistema dopaminergico e un’ipofunzionalità di quello serotoninergico. Naturalmente, si tratta solo di suggerimenti, ma è indubbio che la prevenzione delle gravi conseguenze dello stalking passi anche attraverso l’esplorazione e l’approfondimento delle sue possibili basi neurobiologiche. VA' PENSIERO PAROLE CHIAVE: stalking, neurobiologia, attaccamento, serotonina, dopamina. ISCRIVITI ALLA NOSTRA NEWSLETTER SUMMARY. Nowadays stalking is becoming a real social emergency, as it may often fuel severe aggressive behaviours. No exhaustive aetiological hypothesis is still available regarding this complex phenomenon. -

Emerging Drugs to Treat Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

Review Emerging drugs to treat obsessive-- compulsive disorder † Stefano Pallanti , Giacomo Grassi & Andrea Cantisani † 1. Background UC Davis Health System, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Boulevard, Sacramento, USA 2. Medical need 3. Existing treatments Introduction: Obsessive-- compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic and disabling -- 4. Market review neuropsychiatric disorder with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 1 2% and a rate of treatment resistance of 40%. Other disorders have been 5. Current research goals related to OCD and have been grouped together in a separate DSM-5 chapter, 6. Scientific rational hypothesizing the existence of an ‘OC spectrum’, showing a paradigm shift in 7. Competitive environment the conceptualization of the disorder. 8. Conclusions Areas covered: A review of the most important and recent neurobiological 9. Expert opinion findings that sustain the hypothesis of a more sophisticated model of the disorder is provided, together with a brief overview of the most relevant pharmacological animal models of OCD and its first-line treatments. Current research goals, new compounds tested and the rationale behind the develop- ment of these new pharmacologic agents are then explained and reviewed. Expert opinion: In the past years, no effective novel compounds have emerged for the treatment of OCD, even if many efforts has been made in the study of its neurobiological underpinnings. Relevant changes in the conceptualization of the disorder, suggested by interesting new neurobiological evidences, may result helpful in the development of new treatments. Keywords: anxiety, medication, obsessive-- compulsive disorder, OCD, treatment Expert Opin. Emerging Drugs [Early Online] For personal use only. 1. Background 1.1 Introduction Obsessive-- compulsive disorder (OCD) is a neuropsychiatric disorder affecting approximately 1 -- 2% of the population in their lifetime and is the fourth psychiatric disorder for frequency [1]. -

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Is a Highly Prevalent and Chronic Condition That Is Associated with Substantial Global Disability

PRIMER Obsessive–compulsive disorder Dan J. Stein1*, Daniel L. C. Costa2, Christine Lochner3, Euripedes C. Miguel2, Y. C. Janardhan Reddy4, Roseli G. Shavitt2, Odile A. van den Heuvel5,6 and H. Blair Simpson7 Abstract | Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a highly prevalent and chronic condition that is associated with substantial global disability. OCD is the key example of the ‘obsessive– compulsive and related disorders’, a group of conditions which are now classified together in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, and the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision, and which are often underdiagnosed and undertreated. In addition, OCD is an important example of a neuropsychiatric disorder in which rigorous research on phenomenology , psychobiology , pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy has contributed to better recognition, assessment and outcomes. Although OCD is a relatively homogenous disorder with similar symptom dimensions globally, individualized assessment of symptoms, the degree of insight, and the extent of comorbidity is needed. Several neurobiological mechanisms underlying OCD have been identified, including specific brain circuits that underpin OCD. In addition, laboratory models have demonstrated how cellular and molecular dysfunction underpins repetitive stereotyped behaviours, and the genetic architecture of OCD i s increasingly understood. Effective treatments for OCD include serotonin reuptake i n h i b i t ors a n d c o g ni tive– b e h a v i o ural t h e r a py ,