1 Alexander Bogdanov and the Short History of the Kultintern1 by John Biggart to the Extent That There Was a Mainstream View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Who and What Is Peter Petroff

The University of Manchester Research In and out of the swamp Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Morgan, K. (2013). In and out of the swamp: the unpublished autobiography of Peter Petroff. Scottish Labour History, 48, 23-51. Published in: Scottish Labour History Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:01. Oct. 2021 In and out of the swamp: the unpublished autobiography of Peter Petroff1 Kevin Morgan ‘Who and what is Peter Petroff?’ The question infamously put by the pro-war socialist paper Justice in December 1915 has only ever been partly answered. As the editors of Justice well knew, Petroff (1884-1947) was a leading figure on the internationalist wing of the British Socialist Party (BSP) whom John Maclean had recently invited to Glasgow on behalf of the party’s Glasgow district council. -

Communists and the Labour Party

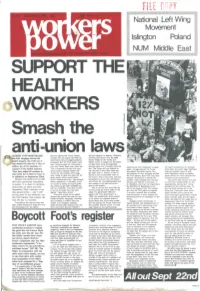

FILE , I cnpv National ~ Left·Wing Movement Islington Poland NUM Middle East ::.;:~:;:;:;:;::::::::::::::::::::::::::~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:;:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~::::::::;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:;:;~~~~~: THE HEALTH Smash,the anti-union laws. Al.-MOST FIVE MONTHS after workers against the Tories. Miners, Bill 't~e designed to destroy. Effective he firSt stoppage during the dockers and, of cour,se, tile Fleet St. working class action is ,to be made totally illegal by the Tories. Suc ealth dispute, the TUC has at electricians, hBve. all '$taged solidarity stoppages. But the TUC leaders have cessful action in support of the health last named the date for a Day of been running scared of a showdown workers must bring the organised Action, by all its ~embers, in with the Tories. Even now, when the working class into a collision with the battle could have threatened to spear the health workers and on strength support of the health workers. TUC is eventually forced into supp law. The Tories will not hesitate to head a struggle against the Tories ening their anti-union legal machinery They have asked all workers to orti ng action, because neither the use that law if they think they can throughout the public sector. But with yet another round of anti- get away with it. Victory in this in stop work for at least an hour in Tories nor the workers will budge, the prospect of such struggles terrifies union legislation aimed at making they refuse to issue any clear call for stance is sure to embolden them in the TUC leaders. Each time they have secret ballots for union officials and in solidarity on Septemller 22nd. -

People, Place and Party:: the Social Democratic Federation 1884-1911

Durham E-Theses People, place and party:: the social democratic federation 1884-1911 Young, David Murray How to cite: Young, David Murray (2003) People, place and party:: the social democratic federation 1884-1911, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3081/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk People, Place and Party: the Social Democratic Federation 1884-1911 David Murray Young A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Durham Department of Politics August 2003 CONTENTS page Abstract ii Acknowledgements v Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1- SDF Membership in London 16 Chapter 2 -London -

British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 William Styles Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge September 2016 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy William Styles British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 This thesis is concerned with an analysis of British governmental attitudes and responses to communism in the United Kingdom during the early years of the Cold War, from the election of the Attlee government in July 1945 up until the election of the Wilson government in October 1964. Until recently the topic has been difficult to assess accurately, due to the scarcity of available original source material. However, as a result of multiple declassifications of both Cabinet Office and Security Service files over the past five years it is now possible to analyse the subject in greater depth and detail than had been previously feasible. The work is predominantly concerned with four key areas: firstly, why domestic communism continued to be viewed as a significant threat by successive governments – even despite both the ideology’s relatively limited popular support amongst the general public and Whitehall’s realisation that the Communist Party of Great Britain presented little by way of a direct challenge to British political stability. Secondly, how Whitehall’s understanding of the nature and severity of the threat posed by British communism developed between the late 1940s and early ‘60s, from a problem considered mainly of importance only to civil service security practices to one which directly impacted upon the conduct of educational policy and labour relations. -

Theory of Money and Credit Centennial Volume.Indb

The University of Manchester Research The Influence of the Currency-Banking Dispute on Early Viennese Monetary Theory Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Mccaffrey, M., & Hülsmann, J. G. (Ed.) (2012). The Influence of the Currency-Banking Dispute on Early Viennese Monetary Theory. In The Theory of Money and Fiduciary Media: Essays in Celebration of the Centennial (pp. 127- 165). Mises Institute. Published in: The Theory of Money and Fiduciary Media Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:01. Oct. 2021 6 M ATTHEW MC C AFFREY The Influence of the Currency-Banking Dispute on Early Viennese Monetary Theory INTRODUCTION Vienna at the beginning of the twentieth century witnessed one of the most remarkable moments in the history of monetary theory. In consecu- tive years, three young economists in Vienna published treatises involving the problems of money and banking: Rudolf Hilferding’s Finance Capital in 1910, Joseph Schumpeter’s Th e Th eory of Economic Development in 1911, and Ludwig von Mises’s Th e Th eory of Money and Credit in 1912. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zoeb Road Ann Arbor

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) dr section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Nordic Race - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Nordic race - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nordic_race From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Nordic race is one of the putative sub-races into which some late 19th- to mid 20th-century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race. People of the Nordic type were described as having light-colored (typically blond) hair, light-colored (typically blue) eyes, fair skin and tall stature, and they were empirically considered to predominate in the countries of Central and Northern Europe. Nordicism, also "Nordic theory," is an ideology of racial supremacy that claims that a Nordic race, within the greater Caucasian race, constituted a master race.[1][2] This ideology was popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in some Central and Northern European countries as well as in North America, and it achieved some further degree of mainstream acceptance throughout Germany via Nazism. Meyers Blitz-Lexikon (Leipzig, 1932) shows famous German war hero (Karl von Müller) as an example of the Nordic type. 1 Background ideas 1.1 Attitudes in ancient Europe 1.2 Renaissance 1.3 Enlightenment 1.4 19th century racial thought 1.5 Aryanism 2 Defining characteristics 2.1 20th century 2.2 Coon (1939) 2.3 Depigmentation theory 3 Nordicism 3.1 In the USA 3.2 Nordicist thought in Germany 3.2.1 Nazi Nordicism 3.3 Nordicist thought in Italy 3.3.1 Fascist Nordicism 3.4 Post-Nazi re-evaluation and decline of Nordicism 3.5 Early criticism: depigmentation theory 3.6 Lundman (1977) 3.7 Forensic anthropology 3.8 21st century 3.9 Genetic reality 4 See also 5 Notes 6 Further reading 7 External links Attitudes in ancient Europe 1 of 18 6/18/2013 7:33 PM Nordic race - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nordic_race Most ancient writers were from the Southern European civilisations, and generally took the view that people living in the north of their lands were barbarians. -

Russian Emigration and British Marxist Socialism

WALTER KENDALL RUSSIAN EMIGRATION AND BRITISH MARXIST SOCIALISM Britain's tradition of political asylum has for centuries brought refugees of many nationalities to her shores. The influence both direct and indirect, which they have exerted on British life has been a factor of no small importance. The role of religious immigration has frequently been examined, that of the socialist emigres from Central Europe has so far received less detailed attention. Engels was a frequent contributor to the "Northern Star" at the time of the Chartist upsurge in the mid-icjth century,1 Marx also contributed.2 George Julian Harney and to a lesser extent other Chartist leaders were measurably influenced by their connection with European political exiles.3 At least one of the immigrants is reputed to have been involved in plans for a Chartist revolt.4 The influence which foreign exiles exerted at the time of Chartism was to be repro- duced, although at a far higher pitch of intensity in the events which preceded and followed the Russian Revolutions of March and October 1917. The latter years of the 19th century saw a marked increase of foreign immigration into Britain. Under the impact of antisemitism over 1,500,000 Jewish emigrants left Czarist Russia between 1881 and 1910, 500,000 of them in the last five years. The number of foreigners in the UK doubled between 1880 and 1901.5 Out of a total of 30,000 Russian, Polish and Roumanian immigrants the Home Office reported that no less than 8,000 had landed between June 1901 and June 1902.6 1 Mark Hovell, The Chartist Movement, Manchester 1925, p. -

Introduction 11. I Have Approached This Subject in Greater Detail in J. D

NOTES Introduction 11. I have approached this subject in greater detail in J. D. White, Karl Marx and the Intellectual Origins of Dialectical Materialism (Basingstoke and London, 1996). 12. V. I. Lenin, Collected Works, Vol. 38, p. 180. 13. K. Marx, Grundrisse, translated by M. Nicolaus (Harmondsworth, 1973), p. 408. 14. N. I. Ziber, Teoriia tsennosti i kapitala D. Rikardo v sviazi s pozdneishimi dopolneniiami i raz"iasneniiami. Opyt kritiko-ekonomicheskogo issledovaniia (Kiev, 1871). 15. N. G. Chernyshevskii, ‘Dopolnenie i primechaniia na pervuiu knigu politicheskoi ekonomii Dzhon Stiuarta Millia’, Sochineniia N. Chernyshevskogo, Vol. 3 (Geneva, 1869); ‘Ocherki iz politicheskoi ekonomii (po Milliu)’, Sochineniia N. Chernyshevskogo, Vol. 4 (Geneva, 1870). Reprinted in N. G. Chernyshevskii, Polnoe sobranie sochineniy, Vol. IX (Moscow, 1949). 16. Arkhiv K. Marksa i F. Engel'sa, Vols XI–XVI. 17. M. M. Kovalevskii, Obshchinnoe zemlevladenie, prichiny, khod i posledstviia ego razlozheniia (Moscow, 1879). 18. Marx to the editorial board of Otechestvennye zapiski, November 1877, in Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Vol. 24, pp. 196–201. 19. Marx to Zasulich, 8 March 1881, in Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Vol. 24, pp. 346–73. 10. It was published in the journal Vestnik Narodnoi Voli, no. 5 (1886). 11. D. Riazanov, ‘V Zasulich i K. Marks’, Arkhiv K. Marksa i F. Engel'sa, Vol. 1 (1924), pp. 269–86. 12. N. F. Daniel'son, ‘Ocherki nashego poreformennogo obshch- estvennogo khoziaistva’, Slovo, no. 10 (October 1880), pp. 77–143. 13. N. F. Daniel'son, Ocherki nashego poreformennogo obshchestvennogo khozi- aistva (St Petersburg, 1893). 14. V. V. Vorontsov, Sud'by kapitalizma v Rossii (St Petersburg, 1882). -

The British and French Representatives to the Communist International, 1920–1939: a Comparative Surveyã

IRSH 50 (2005), pp. 203–240 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859005001938 # 2005 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis The British and French Representatives to the Communist International, 1920–1939: A Comparative Surveyà John McIlroy and Alan Campbell Summary: This article employs a prosopographical approach in examining the backgrounds and careers of those cadres who represented the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Parti Communiste Franc¸ais at the Comintern headquarters in Moscow. In the context of the differences between the two parties, it discusses the factors which qualified activists for appointment, how they handled their role, and whether their service in Moscow was an element in future advancement. It traces the bureaucratization of the function, and challenges the view that these representatives could exert significant influence on Comintern policy. Within this boundary the fact that the French representatives exercised greater independence lends support, in the context of centre–periphery debates, to the judgement that within the Comintern the CPGB was a relatively conformist party. Neither the literature on the Communist International (Comintern) nor its national sections has a great deal to say about the permanent representatives of the national parties in Moscow. The opening of the archives has not substantially repaired this omission.1 From 1920 to 1939 fifteen British communists acted as their party’s representatives to the à This article started life as a paper delivered to the Fifth European Social Science History Conference, Berlin, 24–27 March 2004. Thanks to Richard Croucher, Barry McLoughlin, Emmet O’Connor, Bryan Palmer, Reiner Tosstorff, and all who participated in the ‘‘Russian connections’’ session. -

Pen Pictures of Russia Under the "Red Terror"; (Reminiscences of a Surreptitious Journey to Russia to Attend the Secon

''"' ; •' ; y': : : '}' ' ;•'";; ' ..'.,-.' ;' ','••.; . ' ;-. -/ '}:;: . ...' ;U': M^- ^ ;; :a Pen Pictures of russia UNDER THE Red Terror ir- PEN PICTURES OF RUSSIA To my Friends and Co- Workers W. Gallacher and W. Paul PEN PICTURES OF RUSSIA Under the "Red Terror" (Reminiscences of a surreptitious journey to Russia to attend the Second Congress of the Third International) By JOHN S. CLARKE (Author of " Satires, Lyrics, and Poems ") With Forty-two Illustrations from Photographs taken by the Author and the Soviet Government °M Glasgow : National Workers' Committees, 31 North Frederick Street. 1921 ?m.ft& 7)(C CONTENTS. 1 CHAPTER. PAGE. I. The Home of the Vikings 9 II. On the Murman Coast 23 CO \Z III. O'er Russian Lapland 39 >- IV. In the Heart of Karelia 52 or 03 V. By Solovetski's Shrine 68 VI. Sowers in Seedtime - - 87 VII. Feodor Sergieff - - - - 102 *• VIII. The Corridors of Romance - - 116 - - So IX. The Serpent on the Rock 130 X. Patchwork and Petticoats - - 145 CJ XI. The Reveille of Revolt - - - 159 - - - ^x XII. The Ghosts of Golgotha 196 XIII. The Citadel of Hope - - - 216 XIV. " When Arms are Fair " - - - 239 XV. A Minstrelsy of Sorrow - - - 251 XVI. The Darkness before Dawn - - 272 XVII. A Petersburg Arcadia - - - 294 XVIII. Russland, Farewell! - * - 308 11279*7 ILLUSTRATIONS. ' ' PAGE. Frontispiece—Vladimir Ilytch Oulianoff (Lenin) The North Cape 15 The Murman Coast 19 Main Street, Murmansk 28 A Massacre at Kola 39 A Massacre near Imandra 46 A Massacre near Kovda 53 Kandalaska 60 Monastery of Solovetski 70 A Massacre at Maselskaya 76 Karelian Railway Line 77 A Peasant Student 90 F. -

The Bolshevik Party in Conflict the Left Communist

Ronald I. Kowalski THE BOLSHEVIK PARTY IN CONFLICT THE LEFT COMMUNIST OPPOSITION OF 1918 STUDIES IN SOVIET HISTORY & SOCIETY General Editor: R.W. Davies The Bolshevik Party in Conflict The Left Communist Opposition of 1918 Ronald I. Kowalski Senior Lecturer in Russian History Worcester College ofHigher Education in association with the M Palgrave Macmillan MACMILLAN © Ronald I. Kowalski 1991 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1991 All rights reserved. No reproduction. copy or transmission of this publication may be made without prior permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced. copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright. Designs and Patents Act 1988. or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. 33--4 Alfred Place. London WCIE 7DP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published 1991 Published by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills. Basingstoke. Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world Filmset by Wearside Tradespools. Fulwell. Sunderland British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Kowalski. Ronald I. The Bolshevik Party in conflict: the left Communist opposition of 1918. - (Studies in Soviet history and society). I. Soviet Union. Political events. 1917-1924 I. Title II. University of Birmingham. Centre for Russian and EastEuropean Studies