The Value of Urban Design [Ministry for the Environment]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Planning and Urban Design

5 Urban Planning and Urban Design Coordinating Lead Author Jeffrey Raven (New York) Lead Authors Brian Stone (Atlanta), Gerald Mills (Dublin), Joel Towers (New York), Lutz Katzschner (Kassel), Mattia Federico Leone (Naples), Pascaline Gaborit (Brussels), Matei Georgescu (Tempe), Maryam Hariri (New York) Contributing Authors James Lee (Shanghai/Boston), Jeffrey LeJava (White Plains), Ayyoob Sharifi (Tsukuba/Paveh), Cristina Visconti (Naples), Andrew Rudd (Nairobi/New York) This chapter should be cited as Raven, J., Stone, B., Mills, G., Towers, J., Katzschner, L., Leone, M., Gaborit, P., Georgescu, M., and Hariri, M. (2018). Urban planning and design. In Rosenzweig, C., W. Solecki, P. Romero-Lankao, S. Mehrotra, S. Dhakal, and S. Ali Ibrahim (eds.), Climate Change and Cities: Second Assessment Report of the Urban Climate Change Research Network. Cambridge University Press. New York. 139–172 139 ARC3.2 Climate Change and Cities Embedding Climate Change in Urban Key Messages Planning and Urban Design Urban planning and urban design have a critical role to play Integrated climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies in the global response to climate change. Actions that simul- should form a core element in urban planning and urban design, taneously reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and build taking into account local conditions. This is because decisions resilience to climate risks should be prioritized at all urban on urban form have long-term (>50 years) consequences and scales – metropolitan region, city, district/neighborhood, block, thus strongly affect a city’s capacity to reduce GHG emissions and building. This needs to be done in ways that are responsive and to respond to climate hazards over time. -

Sustainable Urban Design Paradigm: Twenty Five Simple Things to Do to Make an Urban Neighborhood Sustainable

© 2002 WIT Press, Ashurst Lodge, Southampton, SO40 7AA, UK. All rights reserved. Web: www.witpress.com Email [email protected] Paper from: The Sustainable City II, CA Brebbia, JF Martin-Duque & LC Wadhwa (Editors). ISBN 1-85312-917-8 Sustainable urban design paradigm: twenty five simple things to do to make an urban neighborhood sustainable B. A. Kazimee School of Architecture and Construction Management, Washington State University, USA. Abstract Sustainable design celebrates and creates the ability of communities and wider urban systems to minimize their impact on the environment, in an effort to create places that endure, Central to this paradigm is an ecological approach that take into consideration not only the nature but human element as well, locally and globally. The paper presents twenty five design strategies and explores processes that point to a rediscovery of the art and science of designing sustainable neighborhoods. It seeks to synthesize these principles into an agenda for the design of towns and cities with the intention of reversing many of the ills and destructive tendencies of past practices. These strategies serve as indicators to sustainable developmen~ they are used to define inherent qualities, carrying capacities and required ecological footprints to illustrate the place of exemplary communities. Furthermore, they are established to allow designers to model, measure and program sustainable standards as well as monitor the regenerative process of cities. The guidelines are organized under five primary variables for achieving sustainability: human ecology, energy conservation, land and resource conservation (food and fiber,) air and water quality. These variables are presented as highly interactive cycles and are based upon the theory and principles/processes of place making, affordability and sustainability. -

Meaningful Urban Design: Teleological/Catalytic/Relevant

Journal ofUrban Design,Vol. 7, No. 1, 35– 58, 2002 Meaningful Urban Design: Teleological/Catalytic/Relevant ASEEM INAM ABSTRACT Thepaper begins with a critique ofcontemporary urban design:the eldof urban designis vague because it isan ambiguousamalgam of several disciplines, includingarchitecture, landscapearchitecture, urban planningand civil engineering; it issuper cial because itisobsessedwith impressions and aesthetics ofphysical form; and it ispractised as an extensionof architecture, whichoften impliesan exaggerated emphasison theend product. The paper then proposesa meaningful(i.e. truly consequential to improvedquality of life) approach to urban design,which consists of: beingteleological (i.e. driven by purposes rather than de ned by conventional disci- plines);being catalytic (i.e. generating or contributing to long-term socio-economic developmentprocesses); andbeing relevant (i.e. grounded in rst causes andpertinent humanvalues). The argument isillustratedwith a number ofcase studiesof exemplary urban designers,such asMichael Pyatok and Henri Ciriani,and urban designprojects, such asHorton Plazaand Aranya Nagar, from around the world. The paper concludes withan outlineof future directionsin urban design,including criteria for successful urban designprojects (e.g. striking aesthetics, convenient function andlong-term impact) anda proposedpedagogical approach (e.g. interdisciplinary, in-depth and problem-driven). Provocations In the earlypart of 1998,two provocative urban design eventsoccurred at the Universityof Michigan in Ann Arbor.The rstwas an exhibition organizedas partof aninternationalsymposium on ‘ City,Space 1 Globalization’. The second wasa lecture by the renowned Dutch architectand urbanist, Rem Koolhaas. By themselves,the events generated much interestand discussion, yet were innocu- ous,compared to, say, Prince Charles’s controversialcomments on contempor- arycities in the UKorthe gathering momentumof the New Urbanism movementin the USA. -

Urban Design College of Architecture the Univer Sity of Oklahoma

REQUIRE MENTS FOR THE MASTER OF URBAN DESIGN COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE THE UNIVER SITY OF OKLAHOMA For Students Entering the GENERAL REQUIRE MENTS Oklahoma State System Urban Design for Higher Education: Minimum Total Hours (Non-Thesis) . 32 M865 Summer 2018 through Minimum Total Hours (Thesis) . 32 Master of Urban Design Spring 2019 REQUIRED COURSES The master’s degree requires the equivalent of at least two semesters of Required Courses (32 hours): satisfactory graduate work and additional work as may be prescribed for the degree. Core Courses (9 hours): ARCH 6590 Research Methods 3 All coursework applied to the master’s degree must carry graduate credit. ARCH 6680 Urban Design Studio 3 ARCH 6680 Urban Design Studio 3 Master’s degree programs which require a thesis consist of at least 30 Professional Electives (9 hours from the following list of courses): 9 credit hours. All non-thesis master’s degree programs require at least 32 ARCH 5643 Urban Design Analytics credit hours. ARCH 5653 Urban Design Seminar ARCH 5713 Real Estate I Credit transferred from other institutions must meet specific criteria ARCH 5743 Legal Framework for Urban Design and is subject to certain limitations. ARCH 5763 Landscape Architecture for Architects ARCH 5990 Environmental Design Research Methods Courses completed through correspondence study may not be applied ARCH 6643 Urban Design Theory to the master’s degree. L A 5243 Land. Arch. Tech: Materials L A 5343 Land. Arch. Tech: Site Issues To qualify for a graduate degree, students must achieve an overall grade L A 5923 Planting Design point average of 3.0 or higher in the degree program coursework and in RCPL 5003 Global City & Planning Issues all resident graduate coursework attempted. -

Resource List: Community Design Charrettes & Participatory

Resource List: Community Design Charrettes & Participatory Techniques Web Resources American Institute of Architects: Communities by Design Website A community visioning clearinghouse that educates communities on the community design process. http://www.aia.org/liv_default Charrette 101 ASU Stardust Center PowerPoint presentation from December 5, 2008 ‘What is Community?’ workshop. http://stardust.asu.edu/research_resources/detail.php?id=55 Charrette Center.net Online compendium of free information for the community based urban design process. http://www.charrettecenter.net/charrettecenter.asp?a=spf&pfk=7 Making Sustainable Communities Happen Web Resources Resources to help discover ways to foster community sustainability by the ways you live, consume, travel, conserve, plan, and design. http://stardust.asu.edu/research_resources/research_files/31/66/Download_the_Web_Reources_Brochure.pdf National Charrette Institute The National Charrette Institute (NCI) is a nonprofit educational institution that helps people build community capacity for collaboration to create healthy community plans. http://www.charretteinstitute.org/ Publications Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning A resource to understand principles and methods of community design written from the design professional's perspective. Author: Henry Sanoff; Publisher. Publisher: John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2000 Design Charrettes for Sustainable Communities A step‐by‐step guide to more synthetic, holistic, and integrated urban design strategies to create more green, clean, and equitable communities. Author: Patrick M. Condon. Publisher: Island Press, 2007 Livability 101 American Institute of Architect resource to help communities, architects, and public officials understand the basic elements of community design and take advantage of existing tools, strategies, and synergies at the policy, planning and design levels. Authors: Megan M. -

Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines

Chair of Urban Studies and Social Research Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism Bauhaus-University Weimar Fashion in the City and The City in Fashion: Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines Doctoral dissertation presented in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) Maria Skivko 10.03.1986 Supervising committee: First Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Frank Eckardt, Bauhaus-University, Weimar Second Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Stephan Sonnenburg, Karlshochschule International University, Karlsruhe Thesis Defence: 22.01.2018 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 5 Thesis Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Part I. Conceptual Approach for Studying Fashion and City: Theoretical Framework ........................ 16 Chapter 1. Fashion in the city ................................................................................................................ 16 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 16 1.1. Fashion concepts in the perspective ........................................................................................... 18 1.1.1. Imitation and differentiation ................................................................................................ 18 1.1.2. Identity -

Design Charrette

CHARDON TOMORROWUPTOWN Design Charrette i Prepared for: Chardon Tomorrow P.O. Box 1068 Chardon, OH 44024 Ph: 440.273.3077 Email: [email protected] By: Kent State University’s Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative 1309 Euclid Avenue, Suite 200 Cleveland,OH 44106 Ph: 216.357.3434 Email: [email protected] CHARDON TOMORROWUPTOWN Design Charrette TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 01 INTRODUCTION 03 Chardon Tomorrow Previous Initiatives UPTOWN DESIGN CHARRETTE 07 Goals Breakout Session # 1 - Development Breakout Session # 2 - Town Square Breakout Session # 3 - Access & Connectivity IDEAS 15 Small Business Incubator Institutional Anchor Design Guidelines Mixed Use Development Pedestrian-ize Short Court Street Enhance Streetscape Create Child Friendly Park Enhance Courthouse Create Shared Parking Create Safe, Pedestrian Circulators Divert Truck Traffic Bike-friendly Signage and Amenities CASE STUDIES 27 Culpeper, Virginia Kentwood, Michigan Bath, Maine NEXT STEPS 31 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY For the past few years, Chardon Tomorrow has been There were concurrent ideas for these topics developed Development: engaged in visioning and planning exercises to help in each of the three groups. For instance, each group Small Business Incubator create a road map for Chardon’s future. These initiatives suggested that Short Court Street be converted to a Institutional Anchor are aimed at preserving and fostering Chardon’s unique pedestrian and bike-friendly walkway. Another idea with sense of place while achieving economic prosperity broad support is the creation of shared parking spaces Design Guidelines and quality of life. As a next step in their efforts to build on each side of the Square so that patrons can park once Mixed Use Development momentum and engage key stakeholders in this process, and walk easily to various businesses on the Square. -

Urban Design Tools & Resources for the Planning Practitioner Table of Contents

A ROUTLEDGE FREEBOOK URBAN DESIGN TOOLS & RESOURCES FOR THE PLANNING PRACTITIONER TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 :: INTRODUCTION 07 :: 1. THE STREET 48 :: 2. FOOD & BUSINESS: A BIRD IN THE HAND IS WORTH TWO IN THE BUSH 66 :: 3. TRANSFORMATIONS: URBANISM AS TRANSFORMATION 79 :: 4. PEOPLE, PLACES, AND WELLBEING 105 :: 5. EVERYDAY SOCIAL BEHAVIOR AS A BASIS FOR DESIGN introduction HOW TO USE THIS BOOK The five chapters featured in Urban Design: Tools & Resources for the Planning Practitioner—as well as the titles from which we’ve excerpted them—share the goal of making urban areas functional, attractive, and sustainable. Our aim in selecting the excerpts included here was to highlight some of our newest practitioner-oriented titles, and illustrate the global scope of the work being done in this field. In reading through this FreeBook, you’ll find not only that the authors of these selections are based all over the world, but also that their approach to their work reflects a truly global outlook. The focus on practicality in Urban Design makes this FreeBook an ideal resource for urban design practitioners, but it should also prove useful to professionals across the Built Environment, including those in architecture, planning and even urban geographers and policymakers. Although we conceived Urban Design as a cohesive whole, we also encourage you to jump around and take advantage of the chapters that have the most relevance to you. And, of course, keep in mind that all of the titles included here are available in full from our website (www.routledge.com) and other fine booksellers. -

URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINES for the Germantown Employment Area Sector Plan

DRAFT February 2009 URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINES For the Germantown Employment Area Sector Plan Montgomery County Planning Department The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission Germantown 2 Draft Urban Design Guidelines CONTENTS 4 INTRODUCTION Context of Design Guidelines Purpose Urban Design Goals Context 9 AREAWIDE URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINES Streets Open Space Buildings 35 GUIDELINES FOR SPECIFIC AREAS Town Center Cloverleaf District North End Distirct – West Side 3 Germantown INTRODUCTION 1 The Germantown Sector Plan area will be a vibrant urban center for the up-County, a Corridor City along I-270. Served by the MARC commuter line train station and in the future by the Corridor Cities Transitway, Germantown will become a walkable, transit served community. The design guidelines focus on the design of the streets, open spaces and buildings to promote compact, sustainable, and transit accessible development. The proposed street grid will create blocks with housing and jobs within a short walking distance of transit. A variety of open spaces ranging from large stream valley urban parks to small urban spaces will serve the entire up-County and the smaller areas within neighborhoods. The buildings will shape a well knit urban fabric of streets and open spaces that create an enjoyable pedestrian environment. Context of Design Guidelines The design guidelines are one of three guiding documents. Germantown Sector Plan - Identifies the vision and describes the goals for the area. Design Guidelines - Provide a link between the master plan and the zoning, identifies the relationship between the public and private spaces, and communicates the required design features. Zoning Ordinance - Identifies the regulatory framework and the specific development standards that give form to the vision. -

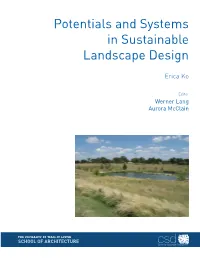

Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design

Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design Erica Ko Editor Werner Lang Aurora McClain csd Center for Sustainable Development II-Strategies Site 2 2.2 Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design Potentials and Systems in Sustainable Landscape Design Erica Ko Based on a presentation by Ilse Frank Figure 1: Five-acre retention pond and native prairie grasses filter and slowly release storm water run-off from adjacent residential development at Mueller Austin, serving an ecological function as well as an aesthetic amenity. Sustainable Landscape Design quickly as possible using heavy urban infra- structure. Today, we are more likely to take Landscape architecture will play an important advantage of the potential for reusing water role in structuring the cities of tomorrow by onsite for irrigation and gray water systems, for allowing landscape strategies to speak more providing habitat, and for slowing storm water closely to shifting cultural paradigms. A de- flows and allowing infiltration to groundwater signed landscape has the ability to illuminate systems—all of which can inspire new forms the interactions between a culture’s view of for integrating water into the built environ- its societal structure and its natural systems. ment. Water can be utilized in remarkable Landscape architecture employs many of the variety of ways–-as a physical boundary, an same design techniques as architecture, but is ecological habitat, or even a waste filtration unique in how it deals with time as a function system. A large-scale example of an outmoded of design (Figure 2), its materials palette, and approach is the Rio Bravo/Rio Grande, which how form is made. -

Ten Principles for Building Healthy Places

Ten Principles for Building Healthy Places Building Healthy Places Initiative 10P_BHP.indd 2 10/21/13 1:32 PM Ten Principles for Building Healthy Places Thomas W. Eitler Edward T. McMahon Theodore C. Thoerig This project was made possible through the generous financial support of James and Sharon Todd. ULI also wishes to acknowledge the following organizations for their help, support, and involvement with this effort: The Colorado Health Foundation, Denver, Colorado The Center for Active Design, New York City The University of Virginia School of Architecture, Center for Design and Health, Charlottesville, Virginia 1 10P_BHP.indd 1 10/21/13 1:32 PM About the Urban Land Institute About the Building Healthy Places Initiative The mission of the Urban Land Institute is to provide leadership Leveraging the power of ULI’s global networks to shape proj- in the responsible use of land and in creating and sustaining ects and places in ways that improve the health of people and thriving communities worldwide. communities. Established in 1936, the Institute today has nearly 30,000 mem- Around the world, communities face pressing health challenges bers, representing the entire spectrum of land use and develop- related to the built environment. For many years, ULI and its ment disciplines. Professionals represented include develop- members have been active players in discussions and projects ers, builders, property owners, investors, architects, planners, that make the link between human health and development; we public officials, real estate brokers, appraisers, attorneys, know that health is a core component of thriving communities. engineers, financiers, academics, and students. In January 2013, ULI’s Board of Directors approved a focus ULI is committed to on healthy communities as a cross-disciplinary theme for the organization. -

Importance of Humane Design for Sustainable Landscape

IACSIT International Journal of Engineering and Technology, Vol. 6, No. 6, December 2014 Importance of Humane Design for Sustainable Landscape S. Toofan energy consumption, transport and the urban footprint[3], [4]. Abstract—Realizing the environmental threats, real or Curiously, and with the recent exception of the compact city potential, to the quality of life, environmental movements have debates [5], this literature has largely neglected the challenge begun in virtually all sectors of industrialized countries, of designing cities as sustainable and live able places which including business, manufacturing, transportation, agriculture, and architecture. Sustainable landscape architecture is one of can adapt their unique cultural identities and specific historic the most incredible fields of design at contemporary topics. heritage to contemporary needs. Conservation and Important problem that will be resolved in this research is sustainability in relation to the patrimony and cultural finding standard spots and positions in urban landscape for heritage of the built environment are core themes. coming to sustainable landscape. The main purpose of this Scientific research continues to provide information about article is investigation of humane factors for better design in all the links between human health and environmental quality. scales of landscape architecture, into special consideration to sustainability. The research method of this paper is Essential components of life-air, water, and food-provide "Descriptive Study", with two strategies: definition of potential pathways for contaminants to affect our health. keywords and discussion about them to receiving useful World health organization said: “Health is a state of complete alternatives. Basic subjects had defined and then major objects physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the had analyzed.