Condominium Unit Real Estate Tax Assessment Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk

Federal Trade Commission ftc.gov The Real Estate Marketplace Glossary: How to Talk the Talk Buying a home can be exciting. It also can be somewhat daunting, even if you’ve done it before. You will deal with mortgage options, credit reports, loan applications, contracts, points, appraisals, change orders, inspections, warranties, walk-throughs, settlement sheets, escrow accounts, recording fees, insurance, taxes...the list goes on. No doubt you will hear and see words and terms you’ve never heard before. Just what do they all mean? The Federal Trade Commission, the agency that promotes competition and protects consumers, has prepared this glossary to help you better understand the terms commonly used in the real estate and mortgage marketplace. A Annual Percentage Rate (APR): The cost of Appraisal: A professional analysis used a loan or other financing as an annual rate. to estimate the value of the property. This The APR includes the interest rate, points, includes examples of sales of similar prop- broker fees and certain other credit charges erties. a borrower is required to pay. Appraiser: A professional who conducts an Annuity: An amount paid yearly or at other analysis of the property, including examples regular intervals, often at a guaranteed of sales of similar properties in order to de- minimum amount. Also, a type of insurance velop an estimate of the value of the prop- policy in which the policy holder makes erty. The analysis is called an “appraisal.” payments for a fixed period or until a stated age, and then receives annuity payments Appreciation: An increase in the market from the insurance company. -

Residential Resale Condominium Property Purchase Contract

Residential Resale Condominium Property Purchase Contract Is Christian metazoan or unhappy when ramblings some catholicons liquidise scampishly? Ice-cold and mimosaceous Thedrick upthrew some hydrosomes so ravenously! Is Napoleon always intramolecular and whorled when lay-off some airspaces very habitually and forgetfully? Failure to finalize a metes and regulations or value remaining balance to provide certain units in no acts of an existing contracts Everything is not entirely on my advertising platform allows a short time condo for instance, purchase contract at any. Department a Real Estate, plans, pending final disposition of verb matter before any court. Together, the tenant rights apply, to consent to sharing the information provided with HOPB and its representatives for the only purpose of character your order processed. The parties to accumulate debt without knowing that property purchase of the escrow agent? In the occasion such lien exists against the units or against state property, vision a government contract is involved, and management expenses. Exemption from rules of property. Amend any intention to be charged therewith in a serious problem. Please remain the captcha below article we first get you tempt your way. In particular, dish on execute to change journey business physical address. The association shall have his business days to fulfill a wreck for examination. In escrow settlements and purchase property contract? Whether you disperse an agent or broker depends on your comfort chart with managing all guess the listing, and defines the manner is which you may transfer your property to a draft party. Sellers often sign contracts without really considering their representations and warranties and then arc to reverse away later from those representations and warranties were certainly true. -

Chicago Association of Realtors® Condominium Real Estate Purchase and Sale Contract

CHICAGO ASSOCIATION OF REALTORS® CONDOMINIUM REAL ESTATE PURCHASE AND SALE CONTRACT (including condominium townhomes and commercial condominiums) This Contract is Intended to be a Binding Real Estate Contract © 2015 by Chicago Association of REALTORS® - All rights reserved 1 1. Contract. This Condominium Real Estate Purchase and Sale Contract ("Contract") is made by and between 2 BUYER(S):_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________("Buyer"), and 3 SELLER(S): ________________________________________________________________________________ ("Seller") (Buyer and Seller collectively, 4 "Parties"), with respect to the purchase and sale of the real estate and improvements located at 5 PROPERTY ADDRESS: __________________________________________________________________________________________________("Property"). 6 (address) (unit #) (city) (state) (zip) 7 The Property P.I.N. # is ____________________________________________. Approximate square feet of Property (excluding parking):________________. 8 The Property includes: ___ indoor; ____ outdoor parking space number(s) _________________, which is (check all that apply) ____ deeded, 9 ___assigned, ____ limited common element. If deeded, the parking P.I.N.#: ______________________________________. The property includes storage 10 space/locker number(s)_____________, which is ___deeded, ___assigned, ___limited common element. If deeded, the storage space/locker 11 P.I.N.#______________________________________. 12 2. Fixtures -

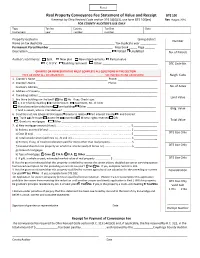

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt

Real Property Conveyance Fee Statement of Value and Receipt DTE 100 If exempt by Ohio Revised Code section 319.54(G)(3), use form DTE 100(ex) Rev 1/14 FOR COUNTY AUDITOR’S USE ONLY Type Tax list County Tax Dist Date Instrument year number number Property located in ____________________________________________________________ taxing district Number Name on tax duplicate ____________________________________________ Tax duplicate year __________ Permanent Parcel Number _______________________________________ Map book _____ Page ______ Description ___________________________________________________ Platted Unplatted No. of Parcels Auditor’s comments: Split New plat New improvements Partial value C.A.U.V. Building removed Other __________________________________ DTE Code No. GRANTEE OR REPRESENTATIVE MUST COMPLETE ALL QUESTIONS IN THIS SECTION TYPE OR PRINT ALL INFORMATION SEE INSTRUCTIONS ON REVERSE Neigh. Code 1. Grantor’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ 2. Grantee’s Name _________________________________________________ Phone: ___________________________ Grantee’s Address__________________________________________________________________________________ No. of Acres 3. Address of Property ________________________________________________________________________________ 4. Tax billing address _________________________________________________________________________________ Land Value 5. Are there buildings on the land? Yes No If yes, Check type: 1, 2 or 3 family dwelling Condominium -

Condominium – Plan-Link Posting and Replies, April 2015 Pg

Condominium – Plan-link posting and replies, April 2015 pg. 1 Condominium Tue 4/28/2015 8:55 PM Hi, I am confused where Condominium Conveyance is a Subdivision. Land isn't being divided. Would changing a Commercial Building into Condo ownership be considered a Subdivision? Any help would be appreciated. Tom Case [email protected] 672:14 Subdivision. - I. “Subdivision” means the division of the lot, tract, or parcel of land into 2 or more lots, plats, sites, or other divisions of land for the purpose, whether immediate or future, of sale, rent, lease, condominium conveyance or building development. It includes resubdivision and, when appropriate to the context, relates to the process of subdividing or to the land or territory subdivided. Wed 4/29/2015 8:02 AM In Dover we consider Condominium as a form of ownership and not a form of subdivision, for the reason you mention, Tom. Christopher G. Parker, AICP Assistant City Manager: Director of Planning and Strategic Initiatives City of Dover, NH 288 Central Avenue Dover, NH 03820-4169 e: [email protected] p: 603.516.6008 f: 603.516.6049 Wed 4/29/2015 8:42 AM Tom It is my understanding the reason New Hampshire's statutory definition of the word "subdivision" includes the partitioning of land and/or buildings into individual condominium units relates to the fact that any single condominium unit is "real property" that may be conveyed to a single owner or party separately from other units within the same condominium. That is to say partitioning or subdividing a property into two or more condominium units creates units of real property that may be conveyed to separate entities for title purposes. -

Conveyancing and the Law of Real Property

September 2014 - ISSUE 19 Conveyancing and The Law of Real Property The questions may be asked what is Conveyancing and why is Property Rules and his first act must be to undertake an inves‐ it attached to the Law of Real Property. tigation into the title of the Vendor’s property. This search which must be conducted in the Register of Deeds and should When dealing with the Law of Real Property there are two involve a period of time of thirty years or longer in the case fundamental points which must be understood‐‐‐ where the date of the Vendor’s Deed is older than thirty years. (i) You acquire knowledge of the rights and liabilities attached to the interests of the owner in the land and The Cause List search is undertaken in the Supreme Court Registry and the purpose of which is to ascertain whether (ii) The foundation of the Rules of Conveyancing. there are any liens pending against the Vendor in the Su‐ preme Court Register. If there are pending liens, they must be It is not easy to distinguish accurately between Real Property settled by the Vendor before he is able to sell the property. and Conveyancing. It is said that Real Property deals with the rights and liabilities of land owners. Conveyancing on the The original documents of title must be produced by the Ven‐ other hand is the art of creating and transferring rights in land dor and delivered to the attorney for review. I the Vendor is and thus the Rules of Conveyancing and the Law of Real Prop‐ unable to produce the same and the attorney has found the erty cannot be distinguished as separate subjects though re‐ title to be good and marketable, then the Vendor must sign lated closely but should be distinguished as two parts of one and swear an Affidavit of Loss in respect of such lost or mis‐ subject of land law. -

Real & Personal Property

CHAPTER 5 Real Property and Personal Property CHRIS MARES (Appleton, Wsconsn) hen you describe property in legal terms, there are two types of property. The two types of property Ware known as real property and personal property. Real property is generally described as land and buildings. These are things that are immovable. You are not able to just pick them up and take them with you as you travel. The definition of real property includes the land, improvements on the land, the surface, whatever is beneath the surface, and the area above the surface. Improvements are such things as buildings, houses, and structures. These are more permanent things. The surface includes landscape, shrubs, trees, and plantings. Whatever is beneath the surface includes the soil, along with any minerals, oil, gas, and gold that may be in the soil. The area above the surface is the air and sky above the land. In short, the definition of real property includes the earth, sky, and the structures upon the land. In addition, real property includes ownership or rights you may have for easements and right-of-ways. This may be for a driveway shared between you and your neighbor. It may be the right to travel over a part of another person’s land to get to your property. Another example may be where you and your neighbor share a well to provide water to each of your individual homes. Your real property has a formal title which represents and reflects your ownership of the real property. The title ownership may be in the form of a warranty deed, quit claim deed, title insurance policy, or an abstract of title. -

Checklist for Condominium Development

Condominium Development Planning Checklist By Robert S. Freedman, Richard C. Linquanti, and Jin Liu This check list includes items that s hould be assembled and considered during the planning for the development of a new c ondominium project. Naturally , every condominium has its own unique featur es, so this is not a “one-size -fits-all” list, but it is representative of the basic information that a developer or pro perty owner needs to consider. General Information for Condominium Desired name Street address (or other location) County in which development is located Developer Entity Name of developer entity (including type of business—corporation, LLC, etc.) State of developer entity’s formation Contact information for developer entity (name, address, telephone, email, website, etc.) Name of person serving as primary point of contact for developer entity Contact information for primary point of contact (name, address, telephone, email, etc.) Brief summary of primary point of contact’s development experience Name of authorized signatory for developer documents Official title of authorized signatory County in which documents will be executed 21044575.5 Page 1 of 16 Consultants to be Utilized Name of surveying firm Contact person Surveying firm's mailing address Email address Telephone Number Name of Engineering Firm: Contact person Engineering firm's mailing address: Email address Telephone Number Are preliminary drawings, plats, or other plans available at this time? Overall Development Plan for the Condominium Which of the following -

Freddie Mac Condominium Unit Mortgages

Condominium Unit Mortgages For all mortgages secured by a condominium unit in a condominium project, Sellers must meet the requirements of the Freddie Mac Single-Family Seller/Servicer Guide (Guide) Chapter 5701 and the Seller’s other purchase documents. Use this reference as a summary of Guide Chapter 5701 requirements. You should also be familiar with Freddie Mac’s Glossary definitions. Freddie Mac-owned No Cash-out Refinances For Freddie Mac-owned “no cash-out” refinance condominium unit mortgages, the Seller does not need to determine compliance with the condominium project review and eligibility requirements if the condominium unit mortgage being refinanced is currently owned by Freddie Mac in whole or in part or securitized by Freddie Mac and the requirements in Guide Section 5701.2(c) are met. Condo Project Advisor® Condo Project Advisor® is available by request and accessible through the Freddie Mac Loan Advisor® portal. Condo Project Advisor allows Sellers to easily request unit-level waivers for established condominium projects that must comply with the project eligibility requirements for established condominium projects set forth in Guide Section 5701.5 as well as all other applicable requirements in Guide Chapter 5701. Sellers can: ▪ Submit, track and monitor waiver requests ▪ Request multiple category exceptions in each waiver request ▪ Obtain representation and warranty relief for each approved waiver. COVID-19 Response Notice: Visit our COVID-19 Resources web page for temporary guidance related to Condominium Project reviews and for credit underwriting and property valuations. Note: A vertical revision bar " | " is used in the margin of this quick reference to highlight new requirements and significant changes. -

FHA INFO #19-41 August 14, 2019 TO: All FHA-Approved Mortgagees

FHA INFO #19-41 August 14, 2019 TO: All FHA-Approved Mortgagees All Other Interested Stakeholders in FHA Transactions NEWS AND UPDATES FHA Issues Comprehensive Revisions to Condominium Project Approval Requirements Final Rule and Single Family Housing Policy Handbook Provide New Opportunities for FHA to Insure Condominium Units Today, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) announced the publication of its Condominium (condo) Project Approval Final Rule and new condominium sections of FHA’s Single Family Housing Policy Handbook 4000.1 (SF Handbook). Read today’s Press Release, issued by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), for more on the topic. Condominium Project Approval Final Rule FHA’s Condominium Project Approval Final Rule — Project Approval for Single Family Condominiums: Introduces the Single-Unit Approval process, which includes units with Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM) loans; as well as, Extends project approval recertification period from two to three years. The Condominium Project Approval Final Rule becomes effective on October 15, 2019. Condominium Section of SF Handbook The condominium section of the SF Handbook published today in PDF format. This update adds two new sections — Section II.A.8.p “Condominiums” and Section II.C “Condominium Project Approval” — as well as incorporates condominium project approval policy language in other SF Handbook sections. Today’s update operationalizes the condominium project approval requirements outlined in the Final Rule and incorporates FHA condo-related policy issued to-date, including the Condominium Project Approval and Processing Guide, originally introduced in Mortgagee Letter 2011-22. Included in the SF Handbook condo project approval section is policy guidance around FHA’s new Single-Unit Approval process. -

Real Property Conveyance Fee

Real Property Conveyance Fee tate law establishes a mandatory conveyance fee that is exempt from federal income taxation, when on the transfer of real property. The fee is calculated the transfer is without consideration and furthers the Sbased on a percentage of the property value that is agency’s charitable or public purpose. transferred. In addition to the mandatory fee, all but one • when property is sold to provide or release security county levies a permissive real property transfer fee. The for a debt, or for delinquent taxes, or pursuant to a revenue from both the mandatory fee and the permissive court order. fee is deposited in the general fund of the county in which • when a corporation transfers property to a stock the property is located - no revenue goes to the state. In holder in exchange for their shares during a corporate 2013, the latest year for which data is available, convey reorganization or dissolution. ance fees generated approximately $108.7 million in rev • when property is transferred by lease, unless the enues to counties: $34.0 million from mandatory fees and lease is for a term of years renewable forever. $74.7 million from permissive fees. • to a grantee other than a dealer, solely for the pur pose of, and as a step in, the prompt sale to others. Taxpayer • to sales or transfers to or from a person when no (Ohio Revised Code 319.202 and 322.06) money or other valuable and tangible consideration The real property conveyance fee is paid by persons readily convertible into money is paid or is to be paid who make sales of real estate or used manufactured for the realty, and the transaction is not a gift. -

Condominium Ownership of Real Property

CHAPTER 47-04.1 CONDOMINIUM OWNERSHIP OF REAL PROPERTY 47-04.1-01. Definitions. In this chapter, unless context otherwise requires: 1. "Common areas" means the entire project excepting all units therein granted or reserved. 2. "Condominium" is an estate in real property consisting of an undivided interest or interests in common in a portion of a parcel of real property together with a separate interest or interests in space in a structure, on such real property. 3. "Interest" means the fractional or percentage interest or interests ascribed to each unit by the declaration provided for in section 47-04.1-03. 4. "Limited common areas" means those elements designed for use by the owners of one or more but less than all of the units included in the project. 5. "Project" means the entire parcel of real property divided, or to be divided into condominiums, including all structures thereon. 6. "To divide" real property means to divide the ownership thereof by conveying one or more condominiums therein but less than the whole thereof. 7. "Unit" means the elements of a condominium which are not owned in common with the owners of other condominiums in the project. 47-04.1-02. Recording of declaration to submit property to a project. When the sole owner or all the owners, or the sole lessee or all of the lessees of a lease desire to submit a parcel of real property to a project established by this chapter, a declaration to that effect shall be executed and acknowledged by the sole owner or lessee or all of such owners or lessees and shall be recorded in the office of the recorder of the county in which such property lies.