Inverness, Earl Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Actress, the English Duchess, and the Privacy Litigation by Amber Melville-Brown

The American Actress, the English Duchess, and the Privacy Litigation By Amber Melville-Brown First Brexit, Now Megzit... trip back to the motherland In a move more resonant with players of the TV were dashed with the event show “Survival” than with members of the British royal postponed amid the CO- family, the Duke and Duchess of Sussex—Prince Harry VID-19 coronavirus pan- and Meghan Markle, the Duchess of Sussex—blindsided demic, even ironically as his senior royals with a unilateral announcement that they father HRH Prince Charles intended to “carve out a progressive new role”1 within the himself actually succumbed royal family, and by the surprise launch of their own and tested positive for the independent website. The relatively sparsely populated virus. www.sussexroyal.com—including a personal statement The couple’s new social about their recently launched media litigation, reference media sites also suffered a to the Royal Rota media system that they are rejecting, blow; the new relationship and to the Information Commissioner’s Office public carved out in negotiations interest test under the Freedom of Information Act—sug- between the royal fam- gests strongly that it is the couple’s tense relationship ily and the couple as they venture out on their own saw with the media that has led them to seek a new “working them having to abandon use of the “Sussex Royal” brand model” in 2020. with which they heralded the new them, before the ink on Indeed, if this announcement was intended to foster the new branding was really even dry. -

THE PRINCE of WALES and the DUCHESS of CORNWALL Background Information for Media

THE PRINCE OF WALES AND THE DUCHESS OF CORNWALL Background Information for Media May 2019 Contents Biography .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Seventy Facts for Seventy Years ...................................................................................................... 4 Charities and Patronages ................................................................................................................. 7 Military Affiliations .......................................................................................................................... 8 The Duchess of Cornwall ............................................................................................................ 10 Biography ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Charities and Patronages ............................................................................................................... 10 Military Affiliations ........................................................................................................................ 13 A speech by HRH The Prince of Wales at the "Our Planet" premiere, Natural History Museum, London ...................................................................................................................................... 14 Address by HRH The Prince of Wales at a service to celebrate the contribution -

Meghan and Harry That They Would Have to Accept What Was on Offer and Not Demand What Was Not

Contents Title Page Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Photo Section Copyright CHAPTER 1 On May 19th 2018, when Meghan Markle stepped out of the antique Rolls Royce conveying her and her mother Doria Ragland from the former Astor stately home Cliveden to St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, where she was due to be married at 12 noon, she was a veritable vision of loveliness. At that moment, one of the biggest names of the age was born. As the actress ascended the steps of St. George’s Chapel, its interior and exterior gorgeously decorated in the most lavish and tasteful spring flowers, she was a picture of demure and fetching modesty, stylish elegance, transparent joyousness, and radiant beauty. The simplicity of her white silk wedding dress, designed by Clare Waight Keller of Givenchy, with its bateau neckline, three-quarter length sleeves, and stark, unadorned but stunningly simple bodice and skirt, coupled with the extravagant veil, five metres long and three metres wide, heavily embroidered with two of her favourite flowers (wintersweet and California poppy, as well as the fifty three native flowers of the various Commonwealth countries, and symbolic crops of wheat, and a piece of the blue dress that the bride had worn on her first date with the groom), gave out a powerful message. All bridal gowns make statements. Diana, Princess of Wales, according to her friend Carolyn Pride, used hers to announce to the world, ‘Here I am. -

On June 2, 1953, Queen Elizabeth II Was Crowned

A Masonic Minute “To the Queen and the Craft” On June 2, 1953, Queen Elizabeth II was crowned “By the grace of God of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of her other realms and territories Queen, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith “ with great pomp and ceremony in Westminster Abbey. ‘Her other realms’ includes Canada. It may justly be said that Her Majesty comes from a Masonic family. Her husband, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, was initiated in 1952, the year of her accession to the throne. Her father, King George VI was an active Freemason. As Prince Albert, Duke of York, he was initiated in 1919, Her great-grandfather, Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, son of Victoria and Albert, was initiated in Sweden in 1868, and served as Grand Master in England from 1874 until his accession as King Edward VII in 1901. Her grandfather, King George V, was not a Freemason, but three of his sons were: Edward, Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII, Albert, Duke of York, later King George VI, and George, Duke of Kent. The Queen’s first cousin, H.R.H. Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, is the Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of England, serving in that office since 1967. The articles of union which joined the rival Grand Lodges, the Moderns and the Ancients in 1813 were signed by two Royal brothers, the Duke of Sussex and Prince Edward, the Duke of Kent as Grand Masters of the respective Grand Lodges The first member of the British royal family to be initiated in England was Frederick Lewis, Prince of Wales, in 1737. -

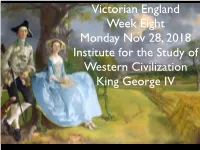

8.Mod Eng.Geoiv.11.27.18X.Key

Victorian England Week Eight Monday Nov 28, 2018 Institute for the Study of Western Civilization King George IV George Prince of Wales Aug 12, 1762 (St James Palace) June 26, 1830 (Windsor) Buried, St Georges Chapel Windsor King George IV, 1762-1830 1762 born first son to K Geo III & Queen Charlotte (15 children) 1783 age 21 gets own home: Carleton House (spends a fortune on it) 1783 meets and falls in love with widow Mrs. Maria Fitzherbert (RC) 1795 debts drowning him, K. Geo III offers money if he marries. 1795 Geo marries Princess Caroline of Brunswick dislikes her on sight. (said she smelled bad, Geo VERY fastidious, Caroline sloppy) 1796 Jan 7 birth of Princess Charlotte (d. 1817) 9 months aft wedding 1800 return of Mrs. Fitzherbert in life of the Prince of wales 1800 Napoleon triumphant takeover of French gov. "First Counsel" 1805 Battle of Trafalgar Adm Horatio Nelson killed at battle. 1810 War in Spain (Wellington) 1810-1811 final insanity of Geo III, Regents Bill in Parliament, 1814 defeat and abdication of Napoleon 1816 marriage of Princess Charlotte to Leopold of Saxe-Coburg 1817 death of Princess Charlotte and her baby. 1815-1820 exile abroad of Princess of Wales Caroline. 1820 death of Geo III, Caroline returns to Eng. War betw K & Q of Eng 1821 July coronation of K. Geo IV, Aug death of Queen Caroline. 1820-1830 reign of King George IV, death of K Geo IV 1830. There were many who did not mourn his passing. "The London Times opined, perhaps rather harshly, that "there never was an individual less regretted by his fellow low-creatures than this deceased King." Prince George’s personality and his interaction with siblings. -

Annual Report 2018−2019

ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST ANNUAL REPORT REPORT COLLECTION TRUST ANNUAL ROYAL 2018−2019 www.rct.uk ANNUAL REPORT 2018−2019 ROYA L COLLECTION TRUST ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2019 www.rct.uk AIMS OF THE ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST CONTENTS In fulfilling The Trust’s objectives, the Trustees’ aims are to ensure that: ~ the Royal Collection (being the works of art ~ the Royal Collection is presented and CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD 5 held by The Queen in right of the Crown interpreted so as to enhance public DIRECTOR’S INTRODUCTION 7 and held in trust for her successors and for the appreciation and understanding; nation) is subject to proper custodial control PRESENTATION AND PARTICIPATION 9 and that the works of art remain available ~ access to the Royal Collection is broadened Visiting the Palaces 9 to future generations; and increased (subject to capacity constraints) ~ Buckingham Palace 9 to ensure that as many people as possible are ~ The Royal Mews 11 ~ the Royal Collection is maintained and able to view the Collection; ~ Windsor Castle 12 conserved to the highest possible standards ~ Clarence House 12 and that visitors can view the Collection ~ appropriate acquisitions are made when ~ Palace of Holyroodhouse 16 in the best possible condition; resources become available, to enhance Exhibitions 21 the Collection and displays of exhibits Historic Royal Palaces & Loans 33 ~ as much of the Royal Collection as possible for the public. INTERPRETATION 37 can be seen by members of the public; Learning 37 Publishing 39 When reviewing future plans, the Trustees ensure that these aims continue to be met and are CARE OF THE COLLECTION 43 in line with the Charity Commission’s general guidance on public benefit. -

HRH the Duchess of Sussex V Associated Newspapers

Neutral Citation Number: [2021] EWHC 273 (Ch) Case No: IL-2019-000110 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE CHANCERY DIVISION BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LIST Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Covid-19 Protocol: This judgment was handed down by the judge remotely by circulation to the parties’ representatives by email and release to Bailii. The date of hand-down is deemed to be as shown opposite: Date: 11 February 2021 Before: THE HON. MR JUSTICE WARBY - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: HRH The Duchess of Sussex Claimant - and - Associated Newspapers Limited Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Ian Mill QC, Justin Rushbrooke QC, Jane Phillips and Jessie Bowhill (instructed by Schillings International LLP) for the Claimant Antony White QC, Adrian Speck QC, Alexandra Marzec, Isabel Jamal and Gervase de Wilde (instructed by Reynolds Porter Chamberlain LLP) for the Defendant Hearing dates: 19-20 January 2021 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment I direct that no official shorthand note shall be taken of this Judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. ............................. Sussex v Associated Newspapers Ltd [2021] EWHC 273 (Ch) Approved Judgment Mr Justice Warby: The action and the application 1. The claimant is well known as the actor, Meghan Markle, who played a leading role in the television series Suits. But she is also well known as the Duchess of Sussex, and wife of HRH Prince Henry of Wales, the Duke of Sussex (“Prince Harry”). The couple were married on 19 May 2018. The relationship between the claimant and her father, Thomas Markle, was difficult at the time. Three months after the wedding, on 27 August 2018, the claimant sent her father a five-page letter (“the Letter”). -

The Royal Family

The Queen • The Queen’s name is Elizabeth Alexandra Mary. • Her royal title is Queen Elizabeth ΙΙ. • She is the head of the Royal Family. • She is the longest serving British monarch. • In 2012, she celebrated her Diamond Jubilee. She had been Queen for 60 years. • She is married to Philip Mountbatten. • She has 4 children; Charles, Anne, Andrew and Edward. Prince Philip • Prince Philip is the Queen’s husband. • His royal title is the Duke of Edinburgh. • His full name is Philip Mountbatten. • He is 98 years old. • Philip is not the king. If he was, he would outrank the Queen. • Philip cannot be king because he was not born into the Royal Family. Prince Charles • Prince Charles is the Queen’s oldest son. • His royal title is the Prince of Wales. • His full name is Charles Philip Arthur George. • When the Queen dies, Prince Charles will become king and head of the Royal Family. • Prince Charles has 2 sons: Prince William and Prince Harry. • In 1976, he started the charity ‘The Prince’s Trust’. The charity helps support young people. Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall • Camilla is married to Prince Charles. • Her full name is Camilla Rosemary Shand. • When Prince Charles becomes king, she will be known as the queen consort. • Camilla has 2 children of her own and is step-mother to Prince Charles’ sons, Prince William and Prince Harry. Prince William • Prince William’s full name is William Arthur Philip Louis. • His royal title is Duke of Cambridge. • He is second in line to the throne after his father, Prince Charles. -

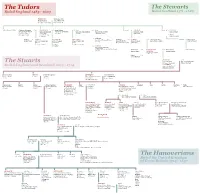

The Stuarts the Tudors the Hanoverians

The Tudors The Stewarts Ruled England 1485 - 1603 Ruled Scotland 1371 - 1603 HENRY VII = Elizabeth of York King of England dau. of Edward IV, (b. 1457, r. 1485-1509) King of England Arthur Prince of Wales Catherine of Aragon (1) = HENRY VIII = (2) Anne Boleyn = (3) Jane = (4) Anne Margaret = JAMES IV Mary = (1) LOUIS XII dau of FERDINAND V. King of England and dau of Earl of Wiltshire dau of Sir John Seymour dau of Duke of Cleves King of Scotland King of France first King of Spain (from 1541) (ex. 1536) (d. 1537) (div 1540 d.1557) (1488-1513) (div 1533. d. 1536.) Ireland (b. 1491, = (2) Charles r. 1509-47) Duke of Suffolk = (5) Catherine (1) (2) Phillip II = MARY I ELIZABETH I EDWARD VI dau of Lord Edmund Howard Madeline = JAMES V = Mary of Lorraine Frances = Henry Grey King of Spain Queen of England and Queen of England King of England and (ex 1542) dau of FRANCIS I. King of Scotland dau of Duke of Guise Duke of Suffolk Ireland and Ireland Ireland King of France (d. 1537) (1513-1542) (b. 1516, r. 1553-8) (b. 1533, r. (b. 1537, r. 1547-53) 1558-1603) = (6) Catherine dau of Sir Thomas Parr (HENRY VIII was her third husband) FRANCIS II (1) = MARY QUEEN = (2) Henry Stuart Lady Jane Grey (d. 1548) King of France OF SCOTS Lord of Darnley (1542-1567. ex 1587) James (3) = Earl of Bothwell JAMES VI = Anne The Stuarts King of Scotland dau. of FREDERICK II, (b. 1566, r. 1567-1625) King of Denmark and JAMES I, Ruled England and Scotland 1603 - 1714 King of England and Ireland (r. -

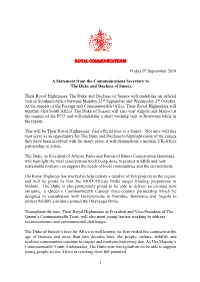

Friday 6Th September 2019 a Statement from The

ROYAL COMMUNICATIONS Friday 6th September 2019 A Statement from the Communications Secretary to The Duke and Duchess of Sussex Their Royal Highnesses The Duke and Duchess of Sussex will undertake an official visit to Southern Africa between Monday 23rd September and Wednesday 2nd October. At the request of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Their Royal Highnesses will together visit South Africa. The Duke of Sussex will also visit Angola and Malawi at the request of the FCO and will undertake a short working visit to Botswana while in the region. This will be Their Royal Highnesses’ first official tour as a family. Not only will this visit serve as an opportunity for The Duke and Duchess to highlight many of the causes they have been involved with for many years, it will demonstrate a modern UK-Africa partnership in action. The Duke, as President of African Parks and Patron of Rhino Conservation Botswana, will highlight the vital conservation work being done to protect wildlife and how sustainable tourism can support the needs of local communities and the environment. His Royal Highness has worked to help initiate a number of key projects in the region, and will be proud to visit the MOD-African Parks ranger training programme in Malawi. The Duke is also particularly proud to be able to deliver an exciting new initiative, a Queen’s Commonwealth Canopy three-country partnership which he designed in consultation with Governments in Namibia, Botswana and Angola to protect wildlife corridors around the Okavango Delta. Throughout the tour, Their Royal Highnesses as President and Vice-President of The Queen’s Commonwealth Trust, will also meet young leaders working to address socio-economic and environmental challenges. -

'It's Good to Be Home,' Markle Says As She Finds Her Voice in US

SUNDAY, AUGUST 16, 2020 08 Biden blasts Trump for ‘abhorrent’ birther rhetoric on Harris ‘It’s good to be home,’ Markle says as she finds her voice in US Meghan Markle said it was “devastating” to return as America’s systemic racism was laid bare following Joe Biden and Kamala Harris the death in police custody of unarmed black man George Floyd in May AFP | Washington Last month the couple filed a Since stepping lawsuit in Los Angeles against hite House hopeful • one or more paparazzi whom WJoe Biden levelled back from the royal they accused of taking pictures fierce criticism at Donald front lines, Harry and of their son Archie without their Trump, with his campaign Meghan have waged permission. saying the president has re- an increasingly bitter “I think what’s so fascinating, sorted to “abhorrent” lies at least from my standpoint and about Democrat Kamala war with the media, my personal experience the past Harris’s eligibility to be vice particularly the couple years (is) the headline president. British tabloid press alone, the clickbait alone makes Biden named Harris, a an imprint,” said Markle. woman of color who was AFP | Washington She added that there is “so born in the United States much toxicity” in certain news and is constitutionally eligi- coverage. ble to be both vice president eghan Markle said she “My husband and I talk about and president, as his run- was pleased to be back it often - this ‘economy for atten- ning mate on Tuesday. She Min America, where she tion’... what is monetizable right quickly faced attacks that plans to speak out against rac- now when you’re looking at the Democrats deemed racist. -

Copyrighted Material

c01.qxp 4/18/07 5:03 PM Page 25 1 THE WIDOW OF WINDSOR QUEEN VICTORIA CAME TO THE BRITISH throne through a series of tragedies and a conflux of familial dereliction. She was born in 1819, in the last full year of the tumultuous reign of her grandfather King George III; his illness had placed his son George at the center of power when the lat- ter assumed the title prince regent for his father in 1811. In 1785 Prince George, a man of insatiable appetites and thoroughly disagreeable reputa- tion, had married his mistress, the Catholic Marie Fitzherbert, in a morga- natic union; the marriage was also illegal under the Act of Settlement, which forbade any heir to the throne to enter into a union with a Roman Catholic. Perpetually in debt as a result of his extravagant building schemes, George eventually—and bigamously—married Princess Caro- line of Brunswick in hopes of gaining a large monetary settlement from Parliament. COPYRIGHTEDTheir union was a disaster from MATERIAL the very beginning: George complained that he found his wife ugly and common, and spent his wed- ding night passed out on the floor; Caroline, in turn, was scarcely enrap- tured with the licentious, grossly overweight prince, who flaunted his continued affair with Lady Jersey before the eyes of the court and his spouse, and both husband and wife proved wildly unfaithful. 25 c01.qxp 4/18/07 5:03 PM Page 26 26 TWILIGHT OF SPLENDOR As time dragged on and relations grew worse, George increasingly humiliated his wife in a series of deliberate acts that won her much sympa- thy; Caroline, in turn, carried on her own affairs, although the public con- tinued to side with her, even through her husband’s unsuccessful attempts to divorce her.