(CRSI) Steering Committee Final Report — a Roadmap to Increased Community Resilience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iaea International Fact Finding Expert Mission of the Fukushima Dai-Ichi Npp Accident Following the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami

IAEA Original English MISSION REPORT THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE EXPERT MISSION IAEA INTERNATIONAL FACT FINDING EXPERT MISSION OF THE FUKUSHIMA DAI-ICHI NPP ACCIDENT FOLLOWING THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI Tokyo, Fukushima Dai-ichi NPP, Fukushima Dai-ni NPP and Tokai Dai-ni NPP, Japan 24 May – 2 June 2011 IAEA MISSION REPORT DIVISION OF NUCLEAR INSTALLATION SAFETY DEPARTMENT OF NUCLEAR SAFETY AND SECURITY IAEA Original English IAEA REPORT THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE EXPERT MISSION IAEA INTERNATIONAL FACT FINDING EXPERT MISSION OF THE FUKUSHIMA DAI-ICHI NPP ACCIDENT FOLLOWING THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI REPORT TO THE IAEA MEMBER STATES Tokyo, Fukushima Dai-ichi NPP, Fukushima Dai-ni NPP and Tokai Dai-ni NPP, Japan 24 May – 2 June 2011 i IAEA ii IAEA REPORT THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE EXPERT MISSION IAEA INTERNATIONAL FACT FINDING EXPERT MISSION OF THE FUKUSHIMA DAI-ICHI NPP ACCIDENT FOLLOWING THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI Mission date: 24 May – 2 June 2011 Location: Tokyo, Fukushima Dai-ichi, Fukushima Dai-ni and Tokai Dai-ni, Japan Facility: Fukushima and Tokai nuclear power plants Organized by: International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) IAEA Review Team: WEIGHTMAN, Michael HSE, UK, Team Leader JAMET, Philippe ASN, France, Deputy Team Leader LYONS, James E. IAEA, NSNI, Director SAMADDAR, Sujit IAEA, NSNI, Head, ISCC CHAI, Guohan People‘s Republic of China CHANDE, S. K. AERB, India GODOY, Antonio Argentina GORYACHEV, A. NIIAR, Russian Federation GUERPINAR, Aybars Turkey LENTIJO, Juan Carlos CSN, Spain LUX, Ivan HAEA, Hungary SUMARGO, Dedik E. BAPETEN, Indonesia iii IAEA SUNG, Key Yong KINS, Republic of Korea UHLE, Jennifer USNRC, USA BRADLEY, Edward E. -

March 2011 Earthquake, Tsunami and Fukushima Nuclear Accident Impacts on Japanese Agri-Food Sector

Munich Personal RePEc Archive March 2011 earthquake, tsunami and Fukushima nuclear accident impacts on Japanese agri-food sector Bachev, Hrabrin January 2015 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/61499/ MPRA Paper No. 61499, posted 21 Jan 2015 14:37 UTC March 2011 earthquake, tsunami and Fukushima nuclear accident impacts on Japanese agri-food sector Hrabrin Bachev1 I. Introduction On March 11, 2011 the strongest recorded in Japan earthquake off the Pacific coast of North-east of the country occurred (also know as Great East Japan Earthquake, 2011 Tohoku earthquake, and the 3.11 Earthquake) which triggered a powerful tsunami and caused a nuclear accident in one of the world’s largest nuclear plant (Fukushima Daichi Nuclear Plant Station). It was the first disaster that included an earthquake, a tsunami, and a nuclear power plant accident. The 2011 disasters have had immense impacts on people life, health and property, social infrastructure and economy, natural and institutional environment, etc. in North-eastern Japan and beyond [Abe, 2014; Al-Badri and Berends, 2013; Biodiversity Center of Japan, 2013; Britannica, 2014; Buesseler, 2014; FNAIC, 2013; Fujita et al., 2012; IAEA, 2011; IBRD, 2012; Kontar et al., 2014; NIRA, 2013; TEPCO, 2012; UNEP, 2012; Vervaeck and Daniell, 2012; Umeda, 2013; WHO, 2013; WWF, 2013]. We have done an assessment of major social, economic and environmental impacts of the triple disaster in another publication [Bachev, 2014]. There have been numerous publications on diverse impacts of the 2011 disasters including on the Japanese agriculture and food sector [Bachev and Ito, 2013; JA-ZENCHU, 2011; Johnson, 2011; Hamada and Ogino, 2012; MAFF, 2012; Koyama, 2013; Sekizawa, 2013; Pushpalal et al., 2013; Liou et al., 2012; Murayama, 2012; MHLW, 2013; Nakanishi and Tanoi, 2013; Oka, 2012; Ujiie, 2012; Yasunaria et al., 2011; Watanabe A., 2011; Watanabe N., 2013]. -

COVID-19: Make It the Last Pandemic

COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city of area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Report Design: Michelle Hopgood, Toronto, Canada Icon Illustrator: Janet McLeod Wortel Maps: Taylor Blake COVID-19: Make it the Last Pandemic by The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness & Response 2 of 86 Contents Preface 4 Abbreviations 6 1. Introduction 8 2. The devastating reality of the COVID-19 pandemic 10 3. The Panel’s call for immediate actions to stop the COVID-19 pandemic 12 4. What happened, what we’ve learned and what needs to change 15 4.1 Before the pandemic — the failure to take preparation seriously 15 4.2 A virus moving faster than the surveillance and alert system 21 4.2.1 The first reported cases 22 4.2.2 The declaration of a public health emergency of international concern 24 4.2.3 Two worlds at different speeds 26 4.3 Early responses lacked urgency and effectiveness 28 4.3.1 Successful countries were proactive, unsuccessful ones denied and delayed 31 4.3.2 The crisis in supplies 33 4.3.3 Lessons to be learnt from the early response 36 4.4 The failure to sustain the response in the face of the crisis 38 4.4.1 National health systems under enormous stress 38 4.4.2 Jobs at risk 38 4.4.3 Vaccine nationalism 41 5. -

Accident Knowledge and Emergency Management

Ris0-R-945(EN) DK9700056 Accident Knowledge and Emergency Management Birgitte Rasmussen, Carsten D. Gr0nberg Ris0 National Laboratory, Roskilde, Denmark March 1997 VOL 2 p III 1 2 Accident Knowledge and Emergency Management Birgitte Rasmussen, Carsten D. Gr0nberg Ris0 National Laboratory, Roskilde, Denmark March 1997 Abstract. The report contains an overall frame for transformation of knowledge and experience from risk analysis to emergency education. An accident model has been developed to describe the emergency situation. A key concept of this model is uncontrolled flow of energy (UFOE), essential ele- ments are the state, location and movement of the energy (and mass). A UFOE can be considered as the driving force of an accident, e.g., an explosion, a fire, a release of heavy gases. As long as the energy is confined, i.e. the location and movement of the energy are under control, the situation is safe, but loss of con- finement will create a hazardous situation that may develop into an accident. A domain model has been developed for representing accident and emergency scenarios occurring in society. The domain model uses three main categories: status, context and objectives. A domain is a group of activities with allied goals and elements and ten specific domains have been investigated: process plant, storage, nuclear power plant, energy distribution, marine transport of goods, marine transport of people, aviation, transport by road, transport by rail and natural disasters. Totally 25 accident cases were consulted and information was extracted for filling into the schematic representations with two to four cases pr. specific domain. The work described in this report is financially supported by EUREKA MEM- brain (Major Emergency Management) project running 1993-1998. -

Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 1 (2015) 72–84

Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 1 (2015) 72–84 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rsase Current situation and needs in man-made and natech risks management using Earth Observation techniques Sabina Di Franco n, Rosamaria Salvatori IIA – CNR, Rome, Italy article info abstract Article history: Received 23 March 2015 The Earth Observation (EO) techniques are becoming increasingly important in risk man- Received in revised form agement activities not only for natural hazards and natural disaster monitoring but also to 9 June 2015 ride out industrial and natech accidents. The latest developments in the aerospace industry Accepted 10 June 2015 Available online 29 July 2015 such as sensors miniaturization and high spatial and temporal resolution missions, devoted to monitoring areas of specific interest, have made the use of EO techniques more efficiently and Keywords: arevreadytobeusedinnearrealtimeconditions.Thispapersummarizethecurrentstateof Natech knowledge on how EO data can be useful in managing all the phases of the Industrial/natech Man-made hazards disaster, and from the environmental conditions before the accident strikes to the post Industrial accident Risk management accident relief, from the scenario setting and planning stage to the damage assessment. Preparedness & 2015 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Emergency Recovery Small satellite UAV Contents 1. Introduction . 73 2. State of the art of the use of EO for industrial and natech risk management . 74 2.1. Explosions....................................................................................... 76 2.2. Fire............................................................................................. 76 2.3. Nuclear accidents. 78 2.4. Oilspills......................................................................................... 80 3. Future development . 80 3.1. Small satellites. 81 3.2. -

PSA Technology Challenges Revealed by the Great East Japan Earthquake

PSA Technology Challenges Revealed by the Great East Japan Earthquake Nathan Siu, Don Marksberry, Susan Cooper, Kevin Coyne, Martin Stutzke Office of Nuclear Regulatory Research U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission Washington, DC, USA PSAM Topical Conference in Light of the Fukushima Dai-Ichi Accident Tokyo, Japan April 15-17, 2013 Abstract This paper presents the current results of an ongoing, limited-scope review of the Fukushima Dai-ichi accident and related events aimed at identifying potential lessons regarding Probabilistic Safety Assessment (PSA) methods, models, tools, and data. The purpose of this review is to: a) support a variety of activities being conducted by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s Office of Nuclear Regulatory Research, including a recently initiated Level 3 PSA project and the planning of future research and development, b) obtain a better understanding of the limitations of current PSA studies, and c) contribute to the PSA community’s dialog on this subject. Several PSA challenges are identified, including challenges that involve the general conduct of current PSAs, as well as those that involve specific technical elements (e.g., human reliability analysis, external events analysis). PSA Technology Challenges Revealed by the Great East Japan Earthquake Nathan Siu*, Don Marksberry, Susan Cooper, Kevin Coyne, Martin Stutzke Office of Nuclear Regulatory Research U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission Washington, DC, USA Abstract: This paper presents the current results of an ongoing, limited-scope review of the Fukushima Dai- ichi accident and related events aimed at identifying potential lessons regarding Probabilistic Safety Assessment (PSA) methods, models, tools, and data. The purpose of this review is to: a) support a variety of activities being conducted by the U.S. -

Pandemic Measures and Chemical Process Safety

Lessons Learned Bulletin Special Issue Chemical Accident Prevention & Preparedness Pandemic measures and chemical process safety The aim of the bulletin is to provide insights on lessons learned from accidents reported in the European Major Accident Reporting System (eMARS) and other accident sources for both industry operators and government regulators. JRC produces at least one CAPP Lessons Learned Bulletin each year. Each issue of the Bulletin focuses on a particular theme. This special issue of the Lessons Introduction Learned Bulletin (LLB) is intended to The Covid-19 pandemic has had a global impact and continues to influence the raise awareness of risks associated with lives of people throughout the whole world. Many industrial facilities have been shutdown and startup of industrial sites shut down following the measures to reduce the spread of infection. Even where dangerous substances are though an industrial facility is not actively manufacturing it may still have present. hazardous substances on site. Following the shut down, operations will restart Protective measures imposed by at some point. Both shut down and start-up are process conditions, which need governments around the world to special attention to prevent the occurrence of chemical accidents. Two recent control the spread of the Covid-19 virus accident cases illustrate why special considerations should be taken when have necessitated the temporary restarting a plant after shutdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic. closure of thousands of sites and substantial reduction in personnel Case studies remaining onsite. As these protection The following reports are of accidents that are very recent and are based on measures are relaxed, site operations media information. -

Development of a Methodology to Assess Man-Made Risks in Germany

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 6, 779–802, 2006 www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci.net/6/779/2006/ Natural Hazards © Author(s) 2006. This work is licensed and Earth under a Creative Commons License. System Sciences Development of a methodology to assess man-made risks in Germany D. Borst1,2, D. Jung1,2, S. M. Murshed1,2, and U. Werner1,2 1University of Karlsruhe (TH), Institute for Finance, Banking and Insurance, 76128 Karlsruhe, Germany 2Center for Disaster Management and Risk Reduction Technology (CEDIM), 76128 Karlsruhe, Germany Received: 27 April 2006 – Revised: 11 July 2006 – Accepted: 11 September 2006 – Published: 22 September 2006 Abstract. Risk is a concept used to describe future poten- 1 State of the art of mapping man-made risks in Ger- tial outcomes of certain actions or events. Within the project many “CEDIM – Risk Map Germany – Man-made Hazards” it is intended to develop methods for assessing and mapping the The objective of the paper is to develop a methodology for as- risk due to different human-induced hazards. This is a task sessing major man-made risks in Germany based on a spatial that has not been successfully performed for Germany so far. analysis of their impacts on people and physical assets. Such Concepts of catastrophe modelling are employed including an approach is needed for mapping this type of risk alongside the spatial modelling of hazard, the compilation of different with risks related to natural hazards. A map server solution, kinds of exposed elements, the estimation of their vulnera- the “Risk Explorer” (cf. Muller¨ et al., 2006), will show both bility and the direct loss potential in terms of human life and natural and human-induced hazards, exposures, vulnerabili- health. -

Annual Report FY 2017-2018

TOWN OF MONTVILLE Annual Report 2017-2018 “A PROUD AND GROWING COMMUNITY” TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF OFFICIALS/BOARDS & COMMISSION MEMBERS ......................................................................... 1 LIST OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE – MONTVILLE …………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 LEGISLATIVE ACTION .............................................................................................................................. 6 ANIMAL CONTROL ................................................................................................................................ 21 BOARD OF ASSESSMENT APPEALS ........................................................................................................ 22 BOARD OF EDUCATION ......................................................................................................................... 23 MONTVILLE EDUCATION FOUNDATION……………………………………………………………………………………………….29 BUILDING DEPARTMENT ....................................................................................................................... 31 COMMISSION ON THE AGING ............................................................................................................... 33 DISPATCH/EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT/FIRE MARSHAL ...................................................................... 34 FINANCE ............................................................................................................................................... 35 GARDNER LAKE AUTHORITY ................................................................................................................ -

Resilience Planning: Tools and Resources for Communities

Resilience Planning: Tools and Resources for Communities November 2020 Resilience Planning: Tools and Resources for Communities OWP EFC at Sacramento State Acknowledgements This research was funded by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) through the Region 9 Environmental Finance Center (EFC) at California State University, Sacramento (Sacramento State) and by the Office of Water Programs (OWP) at Sacramento State. About the EFC at Sacramento State The EFC at Sacramento State is operated by OWP. The EFC serves state and local governments, tribal communities, and the private sector in the areas of financial planning and asset management. Focusing on communities within the US EPA Region 9 that include California, Arizona, Nevada, and Hawaii, the EFC increases capacity of local communities to fund environmental and public health services and adapt to future needs as regulations, technology, and resources change. The EFC is part of the nationwide Environmental Finance Center Network that provides expertise in technical assistance and training for local communities across the country to solve environmental challenges. EPA Region 9 EFC OWP at Sacramento State Modoc Hall, 6000 J St Sacramento, CA 95819 [email protected] (916) 278-6142 Resilience Planning: Tools and Resources for Communities OWP EFC at Sacramento State Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 What is Resilience Planning? ................................................................................................... -

Analysis of Hazardous Material Releases Due to Natural Hazards in the United States

doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.2012.01272.x Analysis of hazardous material releases due to natural hazards in the United States Hatice Sengul, Nicholas Santella, Laura J. Steinberg and Ana Maria Cruz1 Natural hazards were the cause of approximately 16,600 hazardous material (hazmat) releases reported to the National Response Center (NRC) between 1990 and 2008—three per cent of all reported hazmat releases. Rain-induced releases were most numerous (26 per cent of the total), followed by those associated with hurricanes (20 per cent), many of which resulted from major episodes in 2005 and 2008. Winds, storms or other weather-related phenomena were responsible for another 25 per cent of hazmat releases. Large releases were most frequently due to major natural disasters. For instance, hurricane-induced releases of petroleum from storage tanks account for a large fraction of the total volume of petroleum released during ‘natechs’ (understood here as a natural hazard and the hazardous materials release that results). Among the most commonly released chemicals were nitrogen oxides, benzene, and polychlorinated biphenyls. Three deaths, 52 injuries, and the evacuation of at least 5,000 persons were recorded as a consequence of natech events. Overall, results suggest that the number of natechs increased over the study period (1990– 2008) with potential for serious human and environmental impacts. Keywords: chemical release, earthquake, hazardous material, natech (a natural hazard and the hazardous materials release that results), hurricane, natural hazard, oil spill Introduction There is growing evidence that hazardous material (hazmat) releases triggered by natural hazards can pose significant risks to regions that are unprepared for such events. -

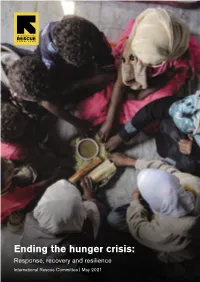

Ending the Hunger Crisis

Ending the hunger crisis: Response, recovery and resilience International Rescue Committee | May 2021 Acknowledgements Written by Alicia Adler, Ellen Brooks Shehata, Christopher Eleftheriades, Laurence Gerhardt, Daphne Jayasinghe, Lauren Post, Marcus Skinner, Helen Stawski, Heather Teixeira and Anneleen Vos with support from Louise Holly and research Company Limited by Guarantee assistance by Yael Shahar and Sarah Sakha. Registration Number 3458056 (England and Wales) Thanks go to colleagues from across the IRC for their helpful insights and important contributions. Charity Registration Number 1065972 Front cover: Family eating a meal, Yemen. Saleh Ba Hayan/IRC Ending the hunger crisis: Response, recovery and resilience Executive summary 1 Introduction 4 1. Humanitarian cash to prevent hunger 7 2. Malnutrition prevention and response 10 3. Removing barriers to humanitarian access 12 4. Climate-resilient food systems that empower women and girls 14 5. Resourcing famine prevention and response 17 Conclusion and recommendations 19 Annex 1 20 Endnotes 21 1 Ending the hunger crisis: Response, recovery and resilience Executive summary Millions on the brink of famine A global hunger crisis – fuelled by conflict, economic turbulence and climate-related shocks – has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The number of people experiencing food insecurity and hunger has risen since the onset of the pandemic. The IRC estimates that the economic downturn alone will drive the number of hungry people up by an additional 35 million in 2021. Without drastic action, the economic downturn caused by COVID-19 will suspend global progress towards ending hunger by at least five years. Of further concern are the 34 million people currently As the world’s largest economies, members of the G7 experiencing emergency levels of acute food insecurity who must work with the international community to urgently according to WFP and FAO warnings are on the brink of deliver more aid to countries at risk of acute food insecurity.