Cancer Pagurus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Monitoring Program for Biodiversity and Non-Indigenous Species in Egypt

UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAM MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN REGIONAL ACTIVITY CENTRE FOR SPECIALLY PROTECTED AREAS National monitoring program for biodiversity and non-indigenous species in Egypt PROF. MOUSTAFA M. FOUDA April 2017 1 Study required and financed by: Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas Boulevard du Leader Yasser Arafat BP 337 1080 Tunis Cedex – Tunisie Responsible of the study: Mehdi Aissi, EcApMEDII Programme officer In charge of the study: Prof. Moustafa M. Fouda Mr. Mohamed Said Abdelwarith Mr. Mahmoud Fawzy Kamel Ministry of Environment, Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) With the participation of: Name, qualification and original institution of all the participants in the study (field mission or participation of national institutions) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS page Acknowledgements 4 Preamble 5 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: Institutional and regulatory aspects 40 Chapter 3: Scientific Aspects 49 Chapter 4: Development of monitoring program 59 Chapter 5: Existing Monitoring Program in Egypt 91 1. Monitoring program for habitat mapping 103 2. Marine MAMMALS monitoring program 109 3. Marine Turtles Monitoring Program 115 4. Monitoring Program for Seabirds 118 5. Non-Indigenous Species Monitoring Program 123 Chapter 6: Implementation / Operational Plan 131 Selected References 133 Annexes 143 3 AKNOWLEGEMENTS We would like to thank RAC/ SPA and EU for providing financial and technical assistances to prepare this monitoring programme. The preparation of this programme was the result of several contacts and interviews with many stakeholders from Government, research institutions, NGOs and fishermen. The author would like to express thanks to all for their support. In addition; we would like to acknowledge all participants who attended the workshop and represented the following institutions: 1. -

TEXT-BOOKS of ANIMAL BIOLOGY a General Zoology of The

TEXT-BOOKS OF ANIMAL BIOLOGY * Edited by JULIAN S. HUXLEY, F.R.S. A General Zoology of the Invertebrates by G. S. Carter Vertebrate Zoology by G. R. de Beer Comparative Physiology by L. T. Hogben Animal Ecology by Challes Elton Life in Inland Waters by Kathleen Carpenter The Development of Sex in Vertebrates by F. W. Rogers Brambell * Edited by H. MUNRO Fox, F.R.S. Animal Evolution / by G. S. Carter Zoogeography of the Land and Inland Waters by L. F. de Beaufort Parasitism and Symbiosis by M. Caullery PARASITISM AND ~SYMBIOSIS BY MAURICE CAULLERY Translated by Averil M. Lysaght, M.Sc., Ph.D. SIDGWICK AND JACKSON LIMITED LONDON First Published 1952 !.lADE AND PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LlMITED, LONDON AND BECCLES CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS vii PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION xi CHAPTER I Commensalism Introduction-commensalism in marine animals-fishes and sea anemones-associations on coral reefs-widespread nature of these relationships-hermit crabs and their associates CHAPTER II Commensalism in Terrestrial Animals Commensals of ants and termites-morphological modifications in symphiles-ants.and slavery-myrmecophilous plants . 16 CHAPTER III From Commensalism to Inquilinism and Parasitism Inquilinism-epizoites-intermittent parasites-general nature of modifications produced by parasitism 30 CHAPTER IV Adaptations to Parasitism in Annelids and Molluscs Polychates-molluscs; lamellibranchs; gastropods 40 CHAPTER V Adaptation to Parasitism in the Crustacea Isopoda-families of Epicarida-Rhizocephala-Ascothoracica -

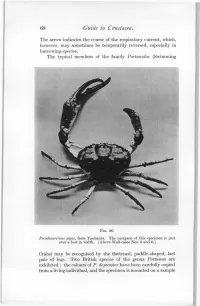

68 Guide to Crustacea

68 Guide to Crustacea. The arrow indicates the course of the respiratory current, which, however, may sometimes be temporarily reversed, especially in burrowing species. The typical members of the family Portunidae (Swimming FIG. 46. Pseudocarcinus gigas, from Tasmania. The carapace of this specimen is just over a foot in width. [Above Wall-cases Nos. 5 and 6.] Crabs) may be recognised by the flattened, paddle-shaped, last pair of legs. Two British species of the genus Portunus are exhibited : the colours of P. depurator have been carefully copied from a living individual, and the specimen is mounted on a sample Decapoda—Brachyura. 69 of the shell-gravel on which it was actually caught. The large Neptunus pelagicus is the commonest edible Crab in many parts of the East. The Common Shore Crab, Carcinus maenas, is also referred to this family, although the paddle-shape of the last legs is not so marked as in the more typical Portunidae. Podophthalmus vigil (Fig. 47) is remarkable for the great length of the eye-stalks, which is quite unusual among the Cyclometopa, and gives this Crab a curious likeness to the genus Macrophthalmus among the Ocypodidae (see Table-case No. 16). The resemblance, however, is quite superficial, for in this case FIG. 47. Podophthalmus vigil (reduced). [Table-case No. 15.] it is the first of the two segments of the eye-stalk which is elongated, while in Macrophthalmus it is the second. The genus Platyonychus, of which a group of specimens is mounted in Wall-case No. 5, also belongs to this family. -

Annelida: Polychaeta) in a Marine Cave of the Ionian Sea (Italy, Central Mediterranean)

J. Mar. Biol. Ass. U.K. (2006), 86,1373^1380 doi: 10.1017/S0025315406014408 Printed in the United Kingdom Recruitment of Serpuloidea (Annelida: Polychaeta) in a marine cave of the Ionian Sea (Italy, central Mediterranean) P O Francesco Denitto* and Margherita Licciano *Laboratorio di Zoogeogra¢a e Faunistica, DiSTeBA, Universita' di Lecce, Via Prov.le Lecce-Monteroni, 73100 Lecce, Italy. O Laboratorio di Zoologia e Simbiosi, DiSTeBA, Universita' di Lecce, Via Prov.le Lecce-Monteroni, 73100 Lecce, Italy. P Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] This paper is the ¢rst attempt to study the recruitment of Serpuloideans in a Mediterranean marine cave through the use of arti¢cial substrates placed in three di¡erent positions, from the entrance to the interior of the cave. This study provides qualitative and quantitative data concerning Serpuloidea recruitment on panels removed successively after one, three, six and 12 months of permanence in the cave. A homogeneous distribution of juveniles Spirorbidae throughout the cave axis had already been detected after one month of panel immersion. Spirorbids were recorded also on panels removed after three months as well as serpulids, which began to be detected during this sampling time, even though represented by just one species. A signi¢cantly di¡erent pattern of distribution throughout the cave axis was observed after only six months, while other serpulids were detected for the ¢rst time. The pattern of species distribution seemed to re£ect the biotic and environmental conditions of the cave. The highest serpuloidean species abundance and diversity was found on panels placed in the intermediate position within the cave. -

D13 the Marine Environment Development Consent Order

ENERGY WORKING FOR BRITAIN FOR WORKING ENERGY Wylfa Newydd Project 6.4.13 ES Volume D - WNDA Development D13 - The marine environment PINS Reference Number: EN010007 Application Reference Number: 6.4.13 June 2018 Revision 1.0 Regulation Number: 5(2)(a) Planning Act 2008 Infrastructure Planning (Applications: Prescribed Forms and Procedure) Regulations 2009 Horizon Internal DCRM Number: WN0902-JAC-PAC-CHT-00045 [This page is intentionally blank] Contents 13 The marine environment .................................................................................. 1 13.1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 13.2 Study area ....................................................................................................... 1 13.3 Wylfa Newydd Development Area baseline environment ................................ 2 Conservation designations .............................................................................. 3 Water quality .................................................................................................... 9 Sediment quality ............................................................................................ 13 Phytoplankton and zooplankton ..................................................................... 15 Marine benthic habitats and species .............................................................. 18 Marine fish .................................................................................................... -

Polychaeta: Serpulidae) from Southeastern Australia

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Knight-Jones, E. W., P. Knight-Jones and L. C. Llewellyn, 1974. Spirorbinae (Polychaeta: Serpulidae) from southeastern Australia. Notes on their taxonomy, ecology, and distribution. Records of the Australian Museum 29(3): 106–151. [1 May 1974]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.29.1974.230 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney naturenature cultureculture discover discover AustralianAustralian Museum Museum science science is is freely freely accessible accessible online online at at www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/ 66 CollegeCollege Street,Street, SydneySydney NSWNSW 2010,2010, AustraliaAustralia o ~------------------~o 25-20 and above 23-17 19- 14 17- 13 ood below 20 20 40 40 ,-- 50 50 Figure I.-Top left, collecting sites near Adelaide; top right, ditto near Sydney; bottom, collecting locations inset, showing also currents of warm, cool (interrupted lines) and cold water (dotted lines). A second smaller arrow-head indicates that the current occasionally reverses. Coastal water types and the mean position of the subtropical convergence (see p. 147) modified from Knox (1963), with mean summer (February) and winter (August) temperatures in degreesC. SPIRORBINAE (POLYCHAETA: SERPULIDAE) FROM SOUTHEASTERN AUSTRALIA. Notes on their Taxonomy, Ecology, and Distribution By E. W. KNIGHT-jONES and PHYLLIS KNIGHT-jONES University College of Swansea, U.K. and L. C. LLEWELLYN, New South Wales State Fisheries, Sydney, Australia Figures 1-14 Manuscript received, 1st September, 1972 SUMMARY Fifteen species belonging to seven genera are described, with pictorial and dichotomous keys to identification and notes on their distribution in other regions. All occur on or adjoining the shore, or on seaweeds cast ashore. -

The Status of Sabellaria Spinulosa Reef Off the Moray Firth and Aberdeenshire Coasts and Guidance for Conservation of the Species Off the Scottish East Coast

The Status of Sabellaria spinulosa Reef off the Moray Firth and Aberdeenshire Coasts and Guidance for Conservation of the Species off the Scottish East Coast Research Summary Scottish Marine and Freshwater Science Vol 11 No 17 The Status of Sabellaria spinulosa Reef off the Moray Firth and Aberdeenshire Coasts and Guidance for Conservation of the Species off the Scottish East Coast B Pearce and J Kimber Introduction and Methodology Sabellaria spinulosa is a gregarious tube dwelling marine polychaete that is known to form extensive reef habitats across Europe. The reef habitats formed by S. spinulosa represent an important habitat for a variety of marine fauna and are thought to provide ecosystem services including the provision of feeding and nursery grounds for some fish species. S. spinulosa reefs have been identified as a priority for protection under the OSPAR Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North East Atlantic and Annex I of the Habitats Directive, in part due to the recognised decline in this habitat across Europe. Until recently, there was little evidence that this habitat occurred in Scottish waters. However, S. spinulosa aggregations with reef-like properties were observed repeatedly between 2011 and 2017 in seabed imagery collected through a variety of sources from the east coast of Scotland. The Scottish Government commissioned this research to assess the conservation status of the newly discovered S. spinulosa habitats and to develop guidance for the future management of this habitat on the east coast of Scotland. Video footage and still images collected from four surveys and ROV clips collected from a fifth, undertaken between 2011 and 2017 (Figure 1) were analysed comprehensively in accordance with established National Marine Biological Analytical Quality Control (NMBAQC) methodologies. -

The Feeding Habits of the Galatheidea. by Edith A

[ 87 ] The Feeding Habits of the Galatheidea. By Edith A. T. Nicol, B A., Ph.D., Department of Zoology. University of Edinburgh. With 7 Figures in the Text. CONTENTS. PAOR INTRODUCTION .... 87 Previous Work 88 Bionomics .... 88 STRUCTURE OF THE MOUTH-PARTS . 89 Galafhea dispersa 89 Porcellana lonyicornis 92 FEEDING HABITS .... 94 Galathea dispersa 94 Deposit feeding . 94 Feeding on large pieces of food 96 Porcellana longicornits 97 The Feeding Mechanism 97 CLEANING MOVEMENTS . 102 DISCUSSION ..... 103 SUMMARY ..... 105 LITERATURE ..... 106 INTRODUCTION. ALTHOUGH the Galatheidea are conspicuous members of the Anomura and occur commonly both on the shore and in deeper water, no account has yet been given of the different methods of feeding which are found within the group. While working at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Plymouth some time ago I became interested, as previous workers have been, in the curiously modified third maxillipeds of Porcellana longicornis, and decided to examine the mode of feeding in this and related forms. My best thanks are due to Dr. E. J. Allen, F.R.S., of the Marine -Biological Association, and to Professor J. H. Orton, of Liverpool University, for every help and encouragement, and also to Professor J- H. Ash worth, F.R.S., of Edinburgh University, for valuable criticism °f the manuscript. 88 EDITH A. T. NICOL. PREVIOUS WORK. Dalyell (1853) describes Porcellana longicornis as the " fanning or ventilating crab," and mentions the alternating see-sawing action of the third maxillipeds fringed with long hairs ; he associates the movements however with respiration. Gosse (1854) points out the use of the maxilli peds in feeding, comparing them with the legs of a barnacle. -

Report of the Working Group on the Biology and Life History of Crabs (WGCRAB)

ICES WGCRAB REPORT 2012 SCICOM STEERING GROUP ON ECOSYSTEM FUNCTIONS ICES CM 2012/SSGEF:08 REF. SSGEF, SCICOM, ACOM Report of the Working Group on the Biology and Life History of Crabs (WGCRAB) 14–18 May 2012 Port Erin, Isle of Man, UK International Council for the Exploration of the Sea Conseil International pour l’Exploration de la Mer H. C. Andersens Boulevard 44–46 DK-1553 Copenhagen V Denmark Telephone (+45) 33 38 67 00 Telefax (+45) 33 93 42 15 www.ices.dk [email protected] Recommended format for purposes of citation: ICES. 2012. Report of the Working Group on the Biology and Life History of Crabs (WGCRAB), 14–18 May 2012. ICES CM 2012/SSGEF:08 80pp. For permission to reproduce material from this publication, please apply to the Gen- eral Secretary. The document is a report of an Expert Group under the auspices of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea and does not necessarily represent the views of the Council. © 2012 International Council for the Exploration of the Sea ICES WGCRAB Report 2012 | i Contents Executive summary ................................................................................................................ 1 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 2 2 Adoption of the agenda ................................................................................................ 2 3 Terms of reference 2011 ................................................................................................ 2 4 -

Southwestern Nova Scotia Snow Crab

Fisheries Pêches and Oceans et Océans DFO Science Maritimes Region Stock Status Report C3-65(2000) Southwestern Nova Scotia Snow Crab Summary Background Snow crab (Chionoecetes opilio) is a crustacean like • In 1999, the catch was 110 t. Catch rates lobster and shrimp, with a flat almost circular body increased in 1998 and 1999 in the and five pairs of spider-like legs. The hard outer Halifax-Lunenburg area. shell is periodically shed in a process called molting. • After molting, crab have a soft shell for a period of A trap survey indicated that adult crab time and are therefore called soft-shelled crab. were present in concentrations in two Unlike lobster, male and female snow crab do not areas, both with cold water bottom continue to molt throughout their lives. Females stop temperature. growing after the molt in which they acquire a wider • Because southwestern Nova Scotia is at abdomen for carrying eggs. This occurs at shell widths less than 95 mm. Male snow crab stop the southern limit of snow crab growing after the molt in which they acquire distribution, it is expected that this relatively large claws on the first pair of legs. This fishery will be sporadic. can occur at shell widths as small as 40 mm. Female crab produce eggs that are carried beneath the abdomen for approximately 2 years. The eggs hatch in late spring or early summer and the tiny newly The Fishery hatched crab larvae spend 12-15 weeks free floating in the water. At the end of this period, they settle on Harvesting of snow crab, Chionoecetes the bottom. -

The Impact of Hydraulic Blade Dredging on a Benthic Megafaunal Community in the Clyde Sea Area, Scotland

Journal of Sea Research 50 (2003) 45–56 www.elsevier.com/locate/seares The impact of hydraulic blade dredging on a benthic megafaunal community in the Clyde Sea area, Scotland C. Hauton*, R.J.A. Atkinson, P.G. Moore University Marine Biological Station Millport (UMBSM), Isle of Cumbrae, Scotland, KA28 0EG, UK Received 4 December 2002; accepted 13 February 2003 Abstract A study was made of the impacts on a benthic megafaunal community of a hydraulic blade dredge fishing for razor clams Ensis spp. within the Clyde Sea area. Damage caused to the target species and the discard collected by the dredge as well as the fauna dislodged by the dredge but left exposed at the surface of the seabed was quantified. The dredge contents and the dislodged fauna were dominated by the burrowing heart urchin Echinocardium cordatum, approximately 60–70% of which survived the fishing process intact. The next most dominant species, the target razor clam species Ensis siliqua and E. arcuatus as well as the common otter shell Lutraria lutraria, did not survive the fishing process as well as E. cordatum, with between 20 and 100% of individuals suffering severe damage in any one dredge haul. Additional experiments were conducted to quantify the reburial capacity of dredged fauna that was returned to the seabed as discard. Approximately 85% of razor clams retained the ability to rapidly rebury into both undredged and dredged sand, as did the majority of those heart urchins Echinocardium cordatum which did not suffer aerial exposure. Individual E. cordatum which were brought to surface in the dredge collecting cage were unable to successfully rebury within three hours of being returned to the seabed. -

The Mediterranean Decapod and Stomatopod Crustacea in A

ANNALES DU MUSEUM D'HISTOIRE NATURELLE DE NICE Tome V, 1977, pp. 37-88. THE MEDITERRANEAN DECAPOD AND STOMATOPOD CRUSTACEA IN A. RISSO'S PUBLISHED WORKS AND MANUSCRIPTS by L. B. HOLTHUIS Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden, Netherlands CONTENTS Risso's 1841 and 1844 guides, which contain a simple unannotated list of Crustacea found near Nice. 1. Introduction 37 Most of Risso's descriptions are quite satisfactory 2. The importance and quality of Risso's carcino- and several species were figured by him. This caused logical work 38 that most of his names were immediately accepted by 3. List of Decapod and Stomatopod species in Risso's his contemporaries and a great number of them is dealt publications and manuscripts 40 with in handbooks like H. Milne Edwards (1834-1840) Penaeidea 40 "Histoire naturelle des Crustaces", and Heller's (1863) Stenopodidea 46 "Die Crustaceen des siidlichen Europa". This made that Caridea 46 Risso's names at present are widely accepted, and that Macrura Reptantia 55 his works are fundamental for a study of Mediterranean Anomura 58 Brachyura 62 Decapods. Stomatopoda 76 Although most of Risso's descriptions are readily 4. New genera proposed by Risso (published and recognizable, there is a number that have caused later unpublished) 76 authors much difficulty. In these cases the descriptions 5. List of Risso's manuscripts dealing with Decapod were not sufficiently complete or partly erroneous, and Stomatopod Crustacea 77 the names given by Risso were either interpreted in 6. Literature 7S different ways and so caused confusion, or were entirely ignored. It is a very fortunate circumstance that many of 1.