Ancient West Mexico in the Mesoamerican Ecumene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ley Orgánica Municipal Del Estado De Michoacán De Ocampo

LEY ORGÁNICA MUNICIPAL DEL ESTADO DE MICHOACÁN DE OCAMPO ÚLTIMA REFORMA PUBLICADA EN EL PERIÓDICO OFICIAL DEL ESTADO, EL 20 DE AGOSTO DE 2018, TOMO: CLXX, NÚMERO: 58, NOVENA SECCIÓN. Ley publicada en la Sección Décima del Periódico Oficial del Estado de Michoacán, el lunes 31 de diciembre de 2001. VÍCTOR MANUEL TINOCO RUBÍ, Gobernador Constitucional del Estado Libre y Soberano de Michoacán de Ocampo, a todos sus habitantes hace saber: El H. Congreso del Estado, se ha servido dirigirme el siguiente DECRETO EL CONGRESO DE MICHOACÁN DE OCAMPO DECRETA: NÚMERO 218 LEY ORGÁNICA MUNICIPAL DEL ESTADO DE MICHOACÁN DE OCAMPO TÍTULO PRIMERO DEL MUNICIPIO Capítulo I Del Objeto de la Ley Artículo 1º. La presente Ley regula el ejercicio de las atribuciones que corresponden a los Municipios del Estado y establece las bases para su gobierno, integración, organización, funcionamiento, fusión y división y regula el ejercicio de las funciones de sus dependencias y entidades, de conformidad con las disposiciones de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos; la Constitución Política del Estado de Michoacán de Ocampo y las demás disposiciones aplicables. Artículo 2º. El Municipio Libre es una entidad política y social investida de personalidad jurídica, con libertad interior, patrimonio propio y autonomía para su 1 gobierno; se constituye por un conjunto de habitantes asentados en un territorio determinado, gobernado por un Ayuntamiento para satisfacer sus intereses comunes. Capítulo II De la División Política Municipal Artículo 3º. El Municipio es la base de la división territorial y de la organización política y administrativa del Estado de Michoacán de Ocampo. -

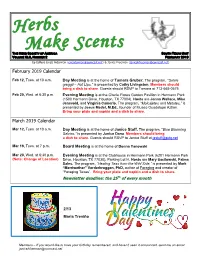

FEBRUARY 2019 Co-Editors Linda Alderman ([email protected]) & Janice Freeman ([email protected])

Herbs Make Scents THE HERB SOCIETY OF AMERICA SOUTH TEXAS UNIT VOLUME XLII, NUMBER 2 FEBRUARY 2019 Co-Editors Linda Alderman ([email protected]) & Janice Freeman ([email protected]) February 2019 Calendar Feb 12, Tues. at 10 a.m. Day Meeting is at the home of Tamara Gruber. The program, “Salvia greggii – Hot Lips,” is presented by Cathy Livingston. Members should bring a dish to share. Guests should RSVP to Tamara at 713-665-0675 Feb 20, Wed. at 6:30 p.m. Evening Meeting is at the Cherie Flores Garden Pavilion in Hermann Park (1500 Hermann Drive, Houston, TX 77004). Hosts are Jenna Wallace, Mike Jensvold, and Virginia Camerlo. The program, “Molcajetes and Metates,” is presented by Jesus Medel, M.Ed., founder of Museo Guadalupe Aztlan. Bring your plate and napkin and a dish to share. March 2019 Calendar Mar 12, Tues. at 10 a.m. Day Meeting is at the home of Janice Stuff. The program, “Blue Blooming Salvias,” is presented by Janice Dana. Members should bring a dish to share. Guests should RSVP to Janice Stuff at [email protected] Mar 19, Tues. at 7 p.m. Board Meeting is at the home of Donna Yanowski Mar 20, Wed. at 6:30 p.m. Evening Meeting is at the Clubhouse in Hermann Park (6201 Hermann Park (Note: Change of Location) Drive, Houston, TX 77030). Parking Lot H. Hosts are Mary Sacilowski, Palma Sales. The program, “Healing Teas from the Wild Side,” is presented by Mark “Merriwether” Vorderbruggen, PhD, author of Foraging and creator of “Foraging Texas”. Bring your plate and napkin and a dish to share. -

With the Protection of the Gods: an Interpretation of the Protector Figure in Classic Maya Iconography

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography Tiffany M. Lindley University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lindley, Tiffany M., "With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2148. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2148 WITH THE PROTECTION OF THE GODS: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE PROTECTOR FIGURE IN CLASSIC MAYA ICONOGRAPHY by TIFFANY M. LINDLEY B.A. University of Alabama, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 © 2012 Tiffany M. Lindley ii ABSTRACT Iconography encapsulates the cultural knowledge of a civilization. The ancient Maya of Mesoamerica utilized iconography to express ideological beliefs, as well as political events and histories. An ideology heavily based on the presence of an Otherworld is visible in elaborate Maya iconography. Motifs and themes can be manipulated to convey different meanings based on context. -

Santa Fe School of Cooking and Market 2005

Santa Fe School of Cooking and Market 2005 santafeschoolofcooking.com Chile Tiles on Back Cover NEW Savor Santa Fe Video— Traditional New Mexican Discover how easy it is to create both red and green chile sauces, enchiladas and the regional food that is indigenous to Santa Fe. Included in the 25-minute video is a full color booklet with photos for the featured recipes: chicken or cheese enchiladas, red and green chile sauce and corn tortillas. In addition, you will receive recipes for pinto beans, posole and bread pudding. After watching this video and creating the food in your own kitchen, you will feel The making of the video with host Nicole like you have visited Santa Fe and the Curtis Ammerman and chef Rocky Durham. School of Cooking. #1 $19.95 FIFTEEN YEARS AND STILL COOKIN!! That’s right. The Santa Fe School of Cooking will be 15 years old in December of 2004. We have seen lots of changes, but the School and Market have the same mission as the day it opened—promoting local agriculture and food products. To spread the word of our great food even further, we recently produced the first of a series of videos touting the glories of Santa Fe and its unique cuisine. Learn the tips and techniques of Southwestern cuisine from the Santa Fe School of Cooking right in your own home. Be sure and check out our great gift ideas for the holidays, birthdays, Father’s and Mother’s days or any day of the year. Our unique gifts are a sure way to send a special gift for a special person. -

Agave Beverage

● ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES Agave salmiana Waiting for the sunrise ‘Tequila to wake the living; mezcal to wake the dead’ - old Mexican proverb. Before corn was ever domesticated, agaves (Agave spp.) identifi ed it with a similar plant found at home. Agaves fl ower only once (‘mono- were one of the main carbohydrate sources for humans carpic’), usually after they are between in what is today western and northern Mexico and south- 8-10 years old, and the plant will then die if allowed to set seed. This trait gives western US. Agaves (or magueyes) are perennial, short- rise to their alternative name of ‘century stemmed, monocotyledonous succulents, with a fl eshy leaf plants’. Archaeological evidence indicates base and stem. that agave stems and leaf bases (the ‘heads’, or ‘cores’) and fl owering stems By Ian Hornsey and ’ixcaloa’ (to cook). The name applies have been pit-cooked for eating in Mes- to at least 100 Mexican liquors that oamerica since at least 9,000 BC. When hey belong to the family Agavaceae, have been distilled with alembics or they arrived, the Spaniards noted that Twhich is endemic to America and Asian-type stills. Alcoholic drinks from native peoples produced ‘agave wine’ whose centre of diversity is Mexico. agaves can be divided into two groups, although their writings do not make it Nearly 200 spp. have been described, according to treatment of the plant: ’cut clear whether this referred to ‘ferment- 150 of them from Mexico, and around bud-tip drinks’ and ’baked plant core ed’ or ‘distilled’ beverages. This is partly 75 are used in that country for human drinks’. -

MEXICO: EARTHQUAKE 06 February 2003 Information Bulletin N° 05/03

MEXICO: EARTHQUAKE 06 February 2003 Information Bulletin N° 05/03 This Information Bulletin is being issued based on the needs described below reflecting the information available at this time. The Situation At 20.08 hours on 21 January, a major earthquake of magnitude 7.8 on the Richter Scale, struck off the coast of Colima state in the west of Mexico, 50 km east of Manzanillo and 500 km west of Mexico City. This is the strongest earthquake to hit Mexico for seven years and significant tremors were also felt in Mexico City, however, no major damage was reported. The government declared a state of emergency in ten towns in Colima state and seven towns in Jalisco state. Buildings collapsed, several hospitals were damaged and there were power outages, gas leakages and damage to the road infrastructure. In the state of Colima, the towns of Colima city, Armería, Coquimatlan, Ixtlahuacan, Villa de Alvarez and Tecomán were the worst affected by the earthquake. Red Cross/Red Crescent Action Official data from the initial results of assessments carried out by the Mexican Red Cross, the Institute of Housing of the State of Colima and the national school of engineers indicate that 29 people died, 1,073 were injured and 43,300 homes were destroyed or damaged by the earthquake, affecting approximately 177,530 people. The release of full, detailed assessment reports remains pending. The following data shows damage in relation to the 11,911 houses surveyed to date in Colima state. Info Bulletin no. 05/03; Mexico: Earthquake State of Total no of Houses -

Los Janamus Grabados De Tzintzuntzan, Michoacán

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.2006.89.2220 VERÓNICA HERNÁNDEZ DÍAZ Los janamus grabados de Tzintzuntzan, Michoacán A mi siempre muy querida maestra, Beatriz de la Fuente Un arte prehispánico y virreinal n Tzintzuntzan, Michoacán, la antigua capital del imperio tarasco, se encuentra un caso excepcional de reutilización de piezas arquitectó- Enicas de origen prehispánico en construcciones virreinales. Se trata de losas, llamadas janamus —en purépecha—, que fueron empotradas tanto en las pirámides de la zona arqueológica como en el convento franciscano de la loca- lidad. Son piedras de basalto pulidas y cortadas con precisión en ángulos rectos y formas rectangulares, cuyas medidas promedio en centímetros son de kg× y el espesor aproximado es de }g. Algunos janamus tienen imágenes grabadas o en bajorrelieve y la mayoría son geométricas, como espirales de varios tipos y círculos combinados con líneas diversas. Apenas unos cuantos muestran diseños de apariencia humana; entre ellos hay uno que destaca especialmente, pues la losa donde se plasmó está colocada de manera horizontal, pero la composición de la imagen es vertical (fig. }). Vista así, la figura se aprecia sentada, con el cuerpo de perfil y encorvado, y las piernas dobladas hacia arriba; apoya sus codos sobre las rodillas, y con las manos sostiene un objeto alargado, que casi alcanza la boca; la cabeza de la figura está de frente, los ojos y la boca son formas circulares ahue- cadas, tiene apéndices o antenas largas que se curvan hacia abajo. ANALESDELINSTITUTODEINVESTIGACIONESESTÉTICAS,NÚM. [uS ¤¤ }u DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.2006.89.2220 }u[ C8-*#8**JJ Es factible reconocer este diseño como un “Flautista”. -

Adeuda El Ingenio $300 Millones a Cañeros

( Reducir la Deuda y Créditos Nuevos Requiere México (INFORMACION COLS . 1 Y 8) 'HOTELAMERICA' -1-' . ' &--&-- SUANFITRION.EN COLIMA MORELOS No . 162 /(a TELS. 2 .0366 Y 2 .95 .96 o~ima COLIMA, COL ., MEX . Fundador Director General Año Colima, Col ., Jueves 16 de Marzo de 1989 . Número XXXV Manuel Sánchez Silva Héctor Sánchez de la Madrid 11,467 Adeuda el Ingenio $300 Millones a Cañeros os Costos del Corte de Caña Provocan Cuevas Isáis : pérdidas por 200 Millones de Pesos Pésimas Ventas en Restaurantes • Situación insólita en la vida de la factoría : Romero Velasco . Cayeron en un 40% • Falso que se mejore punto de sacarosa con ese tipo de corte "Las ventas en la in- dustria restaurantera local I Se ha reducido en 20% el ritmo de molienda por el problema son pésimas, pues han Por Héctor Espinosa Flores decaído en un 40 por ciento, pero pensamos que en esta Independientemente de los problemas tema de corte de la caña se tendrá un me- temporada vacacional de que ha ocasionado la disposición de modi- jor aprovechamiento y por lo tanto un me- Semana Santa y Pascua nos ficar la técnica del corte de caña y que ha jor rendimiento de punto de sacarosa arri- nivelaremos con la llegada a provocado pérdidas a los productores por ba del 8.3 por ciento, pero hasta ahora no Colima de muchos turistas 200 millones de pesos, ahora el ingenio de se ha llegado ni al 8 por ciento, por lo que foráneos aunque no abusa- Quesería tiene un adeudo de 300 millones los productores están confirmando que remos, porque los precios de pesos de la primera preliquidación, al- ese sistema beneflcla, sino que perjudica . -

La Cuenca De Cuitzeo, Michoacán: Patrimonio Arqueológico 297

La cuenca de Cuitzeo, Michoacán: patrimonio arqueológico 297 La cuenca de Cuitzeo, Michoacán: patrimonio arqueológico y ordenamiento territorial Agapi Filini* Introducción La cuenca de Cuitzeo se incluye entre los elementos de mayor importancia para Michoacán y su protección repercute directamente en el bienestar de la población. El patrimonio arqueológico de esta cuenca está ligado directamente a su paisaje natural. Cuitzeo es una región arqueológica y natural de suma importancia para la investigación y promoción de los valores culturales y sociales. Por ende, debe haber una protección legislada para el mismo patrimonio arqueológico y el patri- monio natural. En Cuitzeo, el patrimonio arqueológico está constituido por un número de sitios que se estima supera los 200, pero la cuenca es una área cultural marginada por la falta de investigaciones arqueológicas y de una planeación por parte de las autoridades de los tres niveles de gobierno.1 Un diagnóstico realizado en ciertos municipios de la cuenca de Cuitzeo indica que la mayoría de los sitios arqueológicos han sido presa de saqueo y destrucción. Las actividades ilícitas y el * Centro de Estudios Arqueológicos, El Colegio de Michoacán, La Piedad, Michoacán, México. 1 “En Michoacán existe un extraordinario patrimonio cultural tangible e intangible que se encuentra subutilizado y, en algunos casos, en franco proceso de deterioro” (Go- bierno del Estado, 2008, p. 8). 297 298 Los aspectos culturales y experiencias de participación en el ordenamiento deterioro de los sitios han alentado a varias comunidades a solicitar el apoyo de arqueólogos para protegerlos, pero por la falta de recursos e interés por parte de las autoridades esto no ha sido posible. -

2016-01 Catalog of Fishes. Online Version: (2016): 72 Records

2016-01 Catalog of Fishes. Online Version: (2016): 72 records http://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/ichthyology/catalog/fishcatmain.asp. Genera and Species of Goodeidae W. N. Eschmeyer, R. Fricke, R. van der Laan (eds) albivallis, Crenichthys baileyi Williams [J. E.] & Wilde [G. R.] 1981:489, Fig. 7 [Southwestern Naturalist v. 25 (no. 4); ref. 8991] Preston Big Spring, White Pine County, Nevada, U.S.A. Holotype: UMMZ 203332. Paratypes: UMMZ 203333 (1, allotype); UNLV F-952 (28). •Synonym of Crenichthys baileyi (Gilbert 1893), but a valid subspecies albivallis Williams & Wilde 1981 as described -- (Fuller et al. 1999:322 [ref. 25838], Lazara 2001:71 [ref. 25711], Scoppettone & Rissler 2002:82 [ref. 25956], Scharpf 2007:27 [ref. 30398], Minckley & Marsh 2009:243 [ref. 31114], Page & Burr 2011:452 [ref. 31215]). Current status: Synonym of Crenichthys baileyi (Gilbert 1893). Goodeidae: Empetrichthyinae. Distribution: Springs in White Pine County, Nevada, U.S.A. [subspecies Albivallis]. Habitat: freshwater. atripinnis, Goodea Jordan [D. S.] 1880:299 [Proceedings of the United States National Museum v. 2 (no. 94); ref. 2382] Leon, Guanajuato, Mexico. Lectotype: USNM 23137. Paralectotypes: USNM 23137 (many). Lectotype established (as figured specimen) in caption to Pl. 114, p. 3257 in Jordan & Evermann 1900 [ref. 2446] if figured specimen is identifiable. •Valid as Goodea atripinnis Jordan 1880 -- (Espinosa Pérez et al. 1993:41 [ref. 22290], Nelson et al. 2004:107 [ref. 27807], Miller 2006:281 [ref. 28615], Scharpf 2007:28 [ref. 30398], Miranda et al. 2010:185 [ref. 31345], Page et al. 2013:104 [ref. 32708]). Current status: Valid as Goodea atripinnis Jordan 1880. Goodeidae: Goodeinae. -

Narrative Section of a Successful Application

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Research Programs application guidelines here for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Pre-Columbian Art of the Western and Northern Frontiers of Mesoamerica Institution: California State University, Fresno Project Director: Keith M. Jordan Grant Program: Awards for Faculty at Hispanic-Serving Institutions 400 Seventh Street, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8200 F 202.606.8204 E [email protected] www.neh.gov The Other Ancient Mexico: Pre-Columbian Art of the Western and Northern Frontiers of Mesoamerica Dr. Keith Jordan My project is intended as small step towards rectifying a major gap in education about Mexico’s ancient cultural heritage and reclaiming neglected indigenous art traditions from the margins to which they have been historically relegated in the field of art history. -

Análisis Del Impacto De Las Políticas Ambientales En El Lago De Cuitzeo (1940-2010)

Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía,UNAM ISSN 0188-4611, Núm. 75, 2011, pp. 7-22 Análisis del impacto de las políticas ambientales en el lago de Cuitzeo (1940-2010) Recibido: 21 de abril de 2010. Aceptado en versión final: 2 de febrero de 2011. Celia Franco* Leopoldo Galicia* Leticia Durand** Silke Cram* Resumen. El análisis de la política ambiental permitió re- dad y por carecer de evaluaciones continuas que permitan copilar y evaluar sus impactos en el manejo de los recursos verificar su desempeño. Consecuentemente se ha contribui- pesqueros y en la constitución de las organizaciones sociales do a generar impactos socio ambientales negativos, como la del lago de Cuitzeo, Michoacán, México. Los resultados introducción de especies, el incremento en el número de sugieren cuatro etapas en la política ambiental del lago, pescadores y redes, la pérdida de capacidades organizativas las cuales se han centrado en elevar la productividad sin y la sobrepesca. De ahí que se recomienda la aplicación de implementar medidas para mitigar los impactos negativos evaluaciones constantes de las políticas ambientales para en la diversidad biológica y las variaciones del cuerpo valorar su viabilidad y continuidad desde la perspectiva de agua. El desarrollo de las acciones e instrumentos de socio-ambiental. Así mismo, se considera necesario asegurar política ambiental en el lago han sido centralizadas en la participación de los diferentes actores sociales y la coor- su diseño (intereses, objetivos y metas) y en su operación dinación institucional para favorecer un manejo adecuado desde las dependencias gubernamentales; dejando de lado de los recursos y la conservación del lago.