Merry-Go-Round(From the Austrian)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

L'oeuvre Écrit D'erich Von Stroheim (1) », 1895, N°32, Avril 2001, P

L’oeuvre écrit d’Erich von Stroheim (1) Fanny Lignon To cite this version: Fanny Lignon. L’oeuvre écrit d’Erich von Stroheim (1). 1895 revue d’histoire du cinéma, Paris: Association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinema, 2001, p. 125 à 148. hal-00424715 HAL Id: hal-00424715 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00424715 Submitted on 9 Jul 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. http://www.arias.cnrs.fr/ http://www.univ-lyon1.fr/ Fanny Lignon Maître de conférences Etudes cinématographiques et audiovisuelles Université Lyon 1 Laboratoire ARIAS (CNRS / Paris 3 / ENS) E-mail : [email protected] Publications : http://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/aut/Fanny+Lignon/ LIGNON Fanny « L'oeuvre écrit d'Erich von Stroheim (1) », 1895, n°32, avril 2001, p. 125 à 148. L'OEUVRE ECRIT D'ERICH VON STROHEIM Première partie Les neuf films réalisés par Stroheim entre 1918 et 1931 sont connus de tous les cinéphiles. Les trois romans qu'il a publiés, Poto-Poto, Paprika et les Feux de la Saint Jean, ne jouissent pas de la même notoriété. A cet ensemble, quantitativement modeste, il faut ajouter tous les autres projets auxquels il a participé, et tous ceux qui, pour des raisons souvent indépendantes de sa volonté, n'ont pas pu voir le jour. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Text Machines: Mnemotechnical Infrastructure as Exappropriation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3cj9797z Author McCoy, Jared Publication Date 2020 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Text Machines: Mnemotechnical Infrastructure as Exappropriation DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English by Jared McCoy Dissertation Committee: Professor Andrzej Warminski, Chair Professor Rajagopalan Radhakrishnan Professor Geoffrey Bowker 2020 © 2020 Jared McCoy Dedication TO MY PARENTS for their boundless love and patience …this requires a comprehensive reading of Heidegger that is hard, you know, to do quickly. Paul de Man ii Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................. iii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. v Curriculum Vitae ..................................................................................................................... vi Abstract of the Dissertation .................................................................................................... vii I. History of Inscription ........................................................................................................... -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

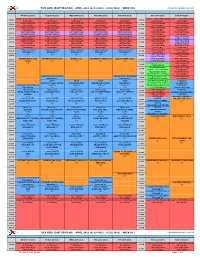

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

THE GETAWAY GIRL: a NOVEL and CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By

THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By EMILY CHRISTINE HOFFMAN Bachelor of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 1999 Master of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2009 THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION Dissertation Approved: Jon Billman Dissertation Adviser Elizabeth Grubgeld Merrall Price Lesley Rimmel Ed Walkiewicz A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to several people for their support, friendship, guidance, and instruction while I have been working toward my PhD. From the English department faculty, I would like to thank Dr. Robert Mayer, whose “Theories of the Novel” seminar has proven instrumental to both the development of The Getaway Girl and the accompanying critical introduction. Dr. Elizabeth Grubgeld wisely recommended I include Elizabeth Bowen’s The House in Paris as part of my modernism reading list. Without my knowledge of that novel, I am not sure how I would have approached The Getaway Girl’s major structural revisions. I have also appreciated the efforts of Dr. William Decker and Dr. Merrall Price, both of whom, in their role as Graduate Program Director, have generously acted as my advocate on multiple occasions. In addition, I appreciate Jon Billman’s willingness to take the daunting role of adviser for an out-of-state student he had never met. Thank you to all the members of my committee—Prof. -

The Abandoned Child in Contemporary German

THE ABANDONED CHILD IN CONTEMPORARY GERMAN LITERATURE AND FILM by Heidrun Jadwiga Kubiessa Tokarz A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Languages and Literature The University of Utah August 2016 Copyright © Heidrun Jadwiga Kubiessa Tokarz 2016 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Heidrun Jadwiga Kubiessa Tokarz has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Katharina Gerstenberger , Chair 02/18/2016 Date Approved Joseph Metz , Member 02/18/2016 Date Approved Karin Baumgartner , Member 02/18/2016 Date Approved Esther Rashkin , Member 02/18/2016 Date Approved Maeera Shreiber , Member 02/18/2016 Date Approved and by Katharina Gerstenberger , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Languages and Literature and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the motif of the abandoned child as a symptom of postwar German memory culture in German literature and film from the late 1980s to the second decade of the 21st century. As part of German postwar memory culture, the abandoned child motif emerged in the early postwar years and established itself in German memory discourse as Kriegskind (war baby), while representing certain war- related experiences of victimization. This study focuses on the change the motif reflects against the backdrop of Germany’s unification, the surge toward normalization, and globalization. The abandoned child motif in German cultural texts at the end of the 20th and at the beginning of the 21st century is a threshold figure which is symptomatic of the past as well as the present, of the victim and the perpetrator, and of suffering as well as guilt. -

February 1905) Winton J

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 2-1-1905 Volume 23, Number 02 (February 1905) Winton J. Baltzell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Baltzell, Winton J.. "Volume 23, Number 02 (February 1905)." , (1905). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/500 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T H H ETl) OH THE ETUDE 47 SCRIBNER’S LATEST BOOR'S f PIANISTS' A DRAMATIC CANTATA OF MODERATE DIFFICULTY A Whole Library THE MUSIC STORY SERlES-(New Volume) JUST PUBLISHED Send 87 cents for the PIANISTS’ Of Technical Exercises THR VIOLIN, bv Paul Stoevlng. Professor of the Violin at th£ Guildhall School^ofMushrin London, F PARLOR ALBUM, a thoroughly Two Magnificent Collections THE COMING OF RUTH high-grade Album, printed from en¬ Condensed Into Less Than One Hundred Pages graved plates upon the finest finished of Vocal Music BV WILLIAM T. NOSS paper, and undoubtedly the finest Price $1.00 each $9.00 per dozen making Album of its kind ever published. -

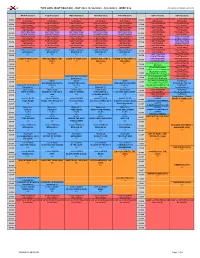

MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM MON (4/26/2021) TUE (4/27/2021) WED (4/28/2021) THU (4/29/2021) FRI (4/30/2021) SAT (5/1/2021) SUN (5/2/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H.