Riparian Vegetation Classification and Mapping: Important Tools for Large-Scale River Corridor Restoration in a Semi-Arid Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campground East of Highway

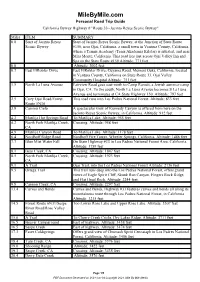

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide California Byway Highway # "Route 33--Jacinto Reyes Scenic Byway" Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 Start of Jacinto Reyes Start of Jacinto Reyes Scenic Byway, at the Junction of State Route Scenic Byway #150, near Ojai, California, a small town in Ventura County, California, where a Tennis Academy (Tenis Akademia Kilatas) is situated, and near Mira Monte, California. This road lies just across Ojai Valley Inn and Spa on the State Route #150 Altitude: 771 feet 0.0 Altitude: 3002 feet 0.7 East ElRoblar Drive East ElRoblar Drive, Cuyama Road, Meiners Oaks, California, located in Ventura County, California on State Route 33, Ojai Valley Community Hospital Altitude: 751 feet 1.5 North La Luna Avenue Fairview Road goes east-north to Camp Ramah, a Jewish summer camp in Ojai, CA. To the south, North La Luna Avenue becomes S La Luna Avenue and terminates at CA State Highway 150. Altitude: 797 feet 2.5 Cozy Ojai Road/Forest This road runs into Los Padres National Forest. Altitude: 833 feet Route 5N34 3.9 Camino Cielo A spectacular view of Kennedy Canyon is offered from here on the Jacinto Reyes Scenic Byway, in California. Altitude: 912 feet 4.2 Matilija Hot Springs Road To Matilija Lake. Altitude: 955 feet 4.2 North Fork Matilija Creek, Crossing. Altitude: 958 feet CA 4.9 Matilija Canyon Road To Matilija Lake. Altitude: 1178 feet 6.4 Nordhoff Ridge Road Nordhoff Fire Tower, Wheeler Springs, California. Altitude: 1486 feet 7.7 Blue Mist Water Fall On State Highway #33 in Los Padres National Forest Area, California. -

To Oral History

100 E. Main St. [email protected] Ventura, CA 93001 (805) 653-0323 x 320 QUARTERLY JOURNAL SUBJECT INDEX About the Index The index to Quarterly subjects represents journals published from 1955 to 2000. Fully capitalized access terms are from Library of Congress Subject Headings. For further information, contact the Librarian. Subject to availability, some back issues of the Quarterly may be ordered by contacting the Museum Store: 805-653-0323 x 316. A AB 218 (Assembly Bill 218), 17/3:1-29, 21 ill.; 30/4:8 AB 442 (Assembly Bill 442), 17/1:2-15 Abadie, (Señor) Domingo, 1/4:3, 8n3; 17/2:ABA Abadie, William, 17/2:ABA Abbott, Perry, 8/2:23 Abella, (Fray) Ramon, 22/2:7 Ablett, Charles E., 10/3:4; 25/1:5 Absco see RAILROADS, Stations Abplanalp, Edward "Ed," 4/2:17; 23/4:49 ill. Abraham, J., 23/4:13 Abu, 10/1:21-23, 24; 26/2:21 Adams, (rented from Juan Camarillo, 1911), 14/1:48 Adams, (Dr.), 4/3:17, 19 Adams, Alpha, 4/1:12, 13 ph. Adams, Asa, 21/3:49; 21/4:2 map Adams, (Mrs.) Asa (Siren), 21/3:49 Adams Canyon, 1/3:16, 5/3:11, 18-20; 17/2:ADA Adams, Eber, 21/3:49 Adams, (Mrs.) Eber (Freelove), 21/3:49 Adams, George F., 9/4:13, 14 Adams, J. H., 4/3:9, 11 Adams, Joachim, 26/1:13 Adams, (Mrs.) Mable Langevin, 14/1:1, 4 ph., 5 Adams, Olen, 29/3:25 Adams, W. G., 22/3:24 Adams, (Mrs.) W. -

Coastal Area Plan

VENTURA COUNTY GENERAL PLAN COASTAL AREA PLAN Last Amended 9-16-08 Ventura County Planning Division Acknowledgements 1978-1982 Ventura County Board of Supervisors David E. Eaton First District Edwin A. Jones Second District J. K. (Ken) MacDonald Third District James R. Dougherty Fourth District Thomas E. Laubacher, Chairman Fifth District Ventura County Planning Commission Vinette Larson First District Earl Meek Second District Glenn Zogg Third District Curran Cummings, Chairman Fourth District Bernice Lorenzi Fifth District Resource Management Agency Victor R. Husbands, Director Planning Division Dennis T. Davis Manager Kim Hocking, Supervisor, Advanced Planning Jeff Walker, Project Manager Trish Davey, Assistant Planner Jean Melvin, Assistant Planner Kheryn Klubnikin, Assistant Planner This Plan was prepared with financial assistance from the Office of Coastal Zone Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, under provisions of the Federal Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972. For Copies/More Info: To purchase the Ventura County Coastal Area Plan: Call 805/654-2805 or go to the Resource Management Agency receptionist 3rd floor of the Government Center Hall of Administration 800 S. Victoria Avenue, Ventura, CA This Coastal Area Plan is also available on our website: http://www.ventura.org/planning VENTURA COUNTY GENERAL PLAN COASTAL AREA PLAN Ventura County Board of Supervisors California Coastal Commission California Coastal Act of 1976 adopted Plan Adopted - November 18, 1980 California Coastal Act amended, effective January, 1981 Amended - April 14, 1981 Conditionally Certified -August 20, 1981 Amended - March 30, 1982 Certified - June 18, 1982 Amended - October 15, 1985 Certified - February 7, 1986 Amended - December 20, 1988 Certified - May 10, 1989 Amended - June 20, 1989 Certified - October 10 & 12, 1989 Amended - December 11, 1990 Certified - March 15, 1991 Amended - October 19, 1993 Certified - February 16, 1994 Amended - December 10, 1996 Certified - April 10, 1997 Amended - Dec. -

California State Parks Western Snowy Plover Management 2009 System-Wide Summary Report

California State Parks Western Snowy Plover Management 2009 System-wide Summary Report In 1993, the coastal population of western snowy plover (WSP) in California, Washington and Oregon was listed as a threatened species under the Federal Endangered Species Act due to habitat loss and disturbance throughout its coastal breeding range. In 2001, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife (USFWS) released a draft WSP recovery plan that identified important management actions needed to restore WSP populations to sustainable levels. Since California State Parks manages about 28% of California’s coastline and a significant portion of WSP nesting habitat, many of the actions called for were pertinent to state park lands. Many of the management recommendations were directed at reducing visitor impacts since visitor beach use overlaps with WSP nesting season (March to September). In 2002, California State Parks developed a comprehensive set of WSP management guidelines for state park lands based on the information contained in the draft recovery plan. That same year a special directive was issued by State Park management mandating the implementation of the most important action items which focused on nest area protection (such as symbolic fencing), nest monitoring, and public education to increase visitor awareness and compliance to regulations that protect plover and their nesting habitat. In 2007 USFWS completed its Final Recovery Plan for the WSP; no new management implications for State Parks. This 2009 State Parks System-wide Summary Report summarizes management actions taken during the 2009 calendar year and results from nest monitoring. This information was obtained from the individual annual area reports prepared by State Park districts offices and by the Point Reyes Bird Observatory - Conservation Science (for Monterey Bay and Oceano Dunes State Vehicular Recreation Area). -

Western Snowy Plover Annual Report 2015 Channel Coast District

Western snowy plover nest inside of a lobster trap. Photo by: Debra Barringer taken at McGrath State Beach 2015 Western Snowy Plover Annual Report 2015 Channel Coast District By Alexis Frangis, Environmental Scientist Nat Cox, Senior Environmental Scientist Federal Fish and Wildlife Permit TE-31406A-1 State Scientific Collecting Permit SC-010923 Channel Coast District 2015 Western Snowy Plover Annual Report Goals and Objectives ................................................................................................................ 3 Ongoing Objectives:................................................................................................................ 3 2014-2015 Management Strategies ......................................................................................... 4 Program Overview and Milestones ......................................................................................... 4 METHODS .............................................................................................................................. 6 Monitoring .............................................................................................................................. 10 MANAGEMENT ACTIONS ............................................................................................... 12 Superintendent’s Closure Order ............................................................................................ 12 Nesting Habitat Protective Fencing ..................................................................................... -

Campings Californië

Campings Californië Angels Camp - Angels Camp RV & Camping Resort Anza-Borrego Desert State Park - Anza-Borrego Desert State Park - Palm Canyon Hotel & RV Resort - The Springs at Borrego RV Resort Bakersfield Cloverdale - River Run RV Park - Cloverdale/Healdsburg KOA - Orange Grove RV Park - Bakersfield RV Resort Coleville - A Country RV Park - Coleville/ Walker KOA - Bakersfield RV Travel Park - Shady Haven RV Park Crescent City, Jedediah Smits Redwood SP - Kern River Campground - Crescent City / Redwoods KOA Holiday - Jedediah Smith Campground Banning - Redwood Meadows RV Resort - Banning Statecoach KOA - Ramblin' Redwoods Campground and RV Barstow Cuyamaca Rancho State Park / Descanso - Barstow/Calico KOA - Paso Picacho Campground - Green Valley Campground - Shady Lane RV Camp - Calico Ghost Town campground Death Valley NP Blythe - Fiddlers Campground - The Cove Colorado River RV resort - Furnace Creek (NPS Campground) - Hidden Beachers Resort - Stovepipe Wells RV Park - Stovepipe Wells (NPS Campground) Bodega Bay - Sunset Campground - Porto Bodega Marina and RV Park - Mesquite Springs Campground - Bodega Bay RV Park - Shoshone RV Park Let op! Tussen juni t/m sept staan de meeste verhuurders Boulevard het niet toe dat je door Death Valley rijdt. - Boulevard/Cleveland National Forest KOA Eureka Buellton (Highway 1) - Shoreline RV Park - Flying Flags RV Resort & Campground - Mad River Rapids RV Park Carlsbad Fresno - South Carlsbad State Beach Campground - Fort Washington Beach Campground - Paradise by the Sea RV Resort - Blackstone -

River Parkway the Ventura

To Upper Ventura River Parkway Coyote Creek & Ojai Valley Trail 33 150 33 Casitas Vista Rd Foster Park Trailhead rve Mile 6.5 se e r p P H k O c T O : o r V Foster Park e n t g u i r a R b i v e r P a r k w a y V i s i o Upper n P l a n , 2 0 0 Big Rock Preserve Mile 6 9 FIGURE ii The Lower Ventura River, looking south from its confl uence with the Canada Larga. 101 Lower PARKWAY LOWER Big Rock Preserve 33 guide to the lower N Ventura Ave Avenue Water ventura river parkway Ojai Valley Treatment Sanitation Plant Plant Canada Larga Creek The Ventura River Parkway is a network of parks, open space, and trails that provide opportunities for recreation, education and stewardship of the Ventura River. the The Ventura River Trail (1999) and the Ojai Valley Trail (1983) provide a continuous v San Buenaventura Canada en multi-use paved path along the Ventura River corridor from the beach all the tu Mission Aqueduct Larga Rd r a Spring St way to the City of Ojai. The trail follows the route of the old Southern r iv Pacific Railroad that once transported Ojai Valley produce to Ventura. e r The 1969 floods washed out much of the tracks, which were later w Brooks Institute of Photography converted from ‘Rails to Trails’. Many side trips provide access to the a t river and creeks as well as scenic overviews of the watershed. -

Beach Wheelchairs Available to Loan for Free

Many sites along the California coast have beach wheelchairs available to loan for free. Typically reservations are not taken; it’s first come-first served. Times and days when they are available vary from site to site. This list was last updated in 2012. We've included the name of the beach/park, contact phone number, and if a motorized beach wheelchair is available in addition to a manual chair. San Diego County Imperial Beach, (619) 685-7972, (motorized) Silver Strand State Beach, (619) 435-0126, (motorized) Coronado City Beach, (619) 522-7346, (motorized) Ocean Beach, San Diego, (619) 525-8247 Mission Beach, San Diego (619) 525-8247, (motorized) La Jolla Shores Beach, South pacific Beach, (619) 525-8247 Torrey Pines State Beach, (858) 755-1275 Del Mar City Beach, (858) 755-1556 San Elijo State Beach, (760) 633-2750 Moonlight Beach, (760) 633-2750 South Carlsbad State Beach, (760) 438-3143 Oceanside City Beach, (760) 435-4018 San Onofre State Beach, (949) 366-8593 Orange County San Clemente City Beach, (949) 361-8219 Doheny State Beach, (949) 496-6172 Salt Creek Beach Park, (949) 276-5050 Aliso Beach, (949) 276-5050 Main Beach, (949) 494-6572 Crystal Cove State Park, (949) 494-3539 Corona del Mar State Beach, (949) 644-3047 Balboa Beach, (949) 644-3047 1 Newport Beach, (949) 644-3047 Huntington State Beach, (714) 536 1454 Huntington City Beach, (714) 536-8083 Bolsa Chica State Beach, (714) 377-5691 Seal Beach, (562) 430-2613 Los Angeles County Cabrillo Beach, (310) 548-7567 Torrance County Beach, (310) 372-2162 Hermosa City Beach, (310) -

2020-2021 Report Card

Beach2020-2021 Report Card 1 HEAL THE BAY // 2020–2021 Beach2020-2021 Report Card We would like to acknowledge that Heal the Bay is located on the traditional lands of the Tongva People and pay our respect to elders both past and present. Heal the Bay is an environmental non-profit dedicated to making the coastal waters and watersheds of Greater Los Angeles safe, healthy and clean. To fulfill our mission, we use science, education, community action and advocacy. The Beach Report Card program is funded by grants from: ©2021 Heal the Bay. All Rights Reserved. The fishbones logo is a trademark of Heal the Bay. The Beach Report Card is a service mark of Heal the Bay. We at Heal the Bay believe the public has the right to know the water quality at their beaches. We are proud to provide West Coast residents and visitors with this information in an easy-to-understand format. We hope beachgoers will use this information to make the decisions necessary to protect their health. HEAL THE BAY CONTENTS2020-2021 • SECTION I: WELCOME EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................7 • SECTION II: WEST COAST SUMMARY CALIFORNIA OVERVIEW ..................................................................10 HONOR ROLL ......................................................................................14 BEACH BUMMERS ..............................................................................16 IMPACT OF BEACH TYPE.................................................................19 -

22Nd in Beachwater Quality 10% of Samples Exceeded National Standards in 2010

CALIFORNIA† See Additional Information About California’s Beach Data Management 22nd in Beachwater Quality 10% of samples exceeded national standards in 2010 Polluted urban and suburban runoff is a major threat to water quality at the nation’s coastal beaches. Runoff from storms and irrigation carries pollution from parking lots, yards, and streets directly to waterways. In some parts of the country, stormwater routinely causes overflows from sewage systems. Innovative solutions known as green infrastructure enable communities to naturally absorb or use runoff before it causes problems. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is modernizing its national rules for sources of runoff pollution and should develop strong, green infrastructure-based requirements. California has more than 500 miles of coastal beaches, spread among over 400 beaches along the Pacific Ocean and San Francisco Bay coastline. The California Department of Health Services administers the BEACH Act grant. Current approved methods for determining fecal indicator bacteria counts in beachwater depend on growth of cultures in samples and take at least 24 hours to process. Because of this, swimmers do not know until the next day if the water they swam in was contaminated. Likewise, beaches may be left closed even after water quality meets standards. There is a great deal of interest in technologies that can provide same-day beachwater quality results. During the 2010 beach season, researchers funded by the California State Water Board and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act tested a rapid method called quantitative polymerase chain reaction, or qPCR, at nine sampling locations in Orange County five days a week. -

A B C Les Numéros En Gras Renvoient Aux Cartes

248 Index Index Les numéros en gras renvoient aux cartes. 7D Experience 177 Beringer Vineyards 198 17-Mile Drive 157 Berkeley 192 555 California Street Building 169 Beverly Hills 91 Beverly Hills City Hall 91 A Beverly Hills Civic Center 92 Beverly Hills Hotel 92 Adventureland 106 Big Sur 151 Agua Caliente Cultural Museum 113 Birch Aquarium at Scripps 67 Ahmanson Theatre 74 Bixby Creek Bridge 152 Alamo Square 185 Bodega Bay 206 Alcatraz 178 Bodega Bay Fisherman’s Festival 206 Alta Plaza Park 182 Bodega Head 206 Anaheim 106 Bodega’s Potter School 206 Andreas Canyon 114 Bodie State Historic Park 135 Andrew Molera State Park 151 Bolinas 205 Angels Flight Railway 75 Bolinas Beach 205 Aquarium of the Bay 177 Bolinas Lagoon 204 Aquarium of the Pacific 100 Borax Museum 121 Arbres de Josué 120 Botanical Building 58 Arcata 212 Brentwood 93 Arcata Marsh and Wildlife Sanctuary 213 Bridalveil Fall 132 Architecture 244 Bridgeway 193 Artist’s Palette 124 Broadway Pier 46 Arts 238 Broadway Street 44 Arts visuels 243 Buena Park 107 Asian Art Museum 183 Buena Vista Park 185 Athenæum Music & Arts Library 66 Buena Vista Winery 202 AT&T Park 188 Buffalo Paddock 187 Audubon Canyon Ranch 205 Burbank 105 Auto Log 129 Autry Museum of the American West 86 C Avenue of the Giants 209 Avila Adobe 72 Cable Car Museum 177 Cable cars 176 Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 99 B Cabrillo National Monument 62 Badwater 123 Cabrillo National Monument Visitor Center 62 Baignade 222 Caffe Trieste 174 Balboa Park 55 California Academy of Sciences 186 Balboa Park Carousel 60 California -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Roy Stearns March 11, 2002 (916) 654-7538

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Roy Stearns March 11, 2002 (916) 654-7538 “Earth Day” Effort Doubles… Thousands Expected to Help Fix California’s Environment Huge Earth Day Turnout heading for 36 State Parks in 20 California Counties on Saturday, April 20 SACRAMENTO – One of the organizing groups for this years Earth Day activities says their effort statewide will be double that of last years activities. According to the California State Parks Foundation, more than $100,000 is being sent out to fund more than 40 projects, in 36 California State Parks, in 20 California Counties from Northern California to Southern California. “The overall effort,” said Susan Smartt, President of the California State Parks Foundation, “is one of our biggest in recent years. It includes a vast array of projects designed to restore and rehabilitate our treasured parks, everything from stream and hillside restoration, to improvement of trail systems and tree plantings. People all across California have a strong attachment to their environment and on this day they turn out to prove it.” California State Parks is joining with the California State Parks Foundation to participate in Earth Day events and projects throughout the state on Saturday, April 20. The Earth Day mission is to initiate cleanup and restoration projects at State Parks and community parks. For energy efficient recreation - California State Parks on the Internet: <http://www.parks.ca.gov> 2 California State Parks Acting Director Ruth Coleman said, “Earth Day is the perfect opportunity to remember – and celebrate – what makes California great – our land, and what better place to do this than in California State Parks.