Rural Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PM Netanyahu and Quartet Rep Blair Announce Economic Steps to Assist

Arabs, Jews to travel to Poland together Special delegation of Jewish, Arab, Druze, Bedouin and Christian students to visit concentration camps, learn about 'the other.' 'We're leaving as a united group of friends,' one student says Tomer Velmer A unique group consisting of 220 Jewish, Arab, Druze, Bedouin and Christians teenagers is expected to visit Nazi concentration camps in Poland later this month. The participants are all students at Amal high schools across Israel. The trip will be held under the banner, "We are all part of same human fabric." Amal Group Director Shimon Cohen wrote a letter to the students, asking them to bring with them on their journey not just food and clothing but also patience, openness and attentiveness. The group decided to allow the students to experience both the suffering the Jewish people have gone through and the pain caused to other nations and religions in an attempt to acknowledge "the other". Preparing for the journey (Photo: Sami Kara) Many Amal schools are taking part in the special mission, including those in Shefaram, Rahat, Dimona, Hadera, Ofakim, and Kiryat Malakhi. Each student will pay roughly NIS 5,000 ($1,360) for the trip, part of which will be subsidized by Amal and the Education Ministry. Throughout their visit, the students will be divided into integrated groups consisting of Arab, Hebrew and English speakers. One big united group In preparation for their trip the students participated in a series of meetings aimed at connecting the different worlds they all come from. "The first few meetings were awkward for them due to cultural differences, and the fact that not all of them speak Hebrew," the project manager said. -

Paths in Education

Introduction ................................................................................... 461 The Knesset ................................................................................... 461 The parties ..................................................................................... 462 The budget ..................................................................................... 467 The local authorities....................................................................... 469 The professional organizations (Teachers' Unions) ....................... 470 The parents..................................................................................... 476 The Academy ................................................................................. 483 The Media ...................................................................................... 487 The State Comptroller .................................................................... 488 Chapter Five: Events that occurred in the Israeli education system and illustrate the policy-making processes .............. 489 Introduction ................................................................................... 489 Problems within the area of social integration in education ........... 489 Integration versus differentiation ................................................... 505 Education in the developmental areas ............................................ 514 The phenomenon of "Bussing" ...................................................... 526 Local government -

Rocument RESUME ED 045 767 UD 011 084 Education in Israel3

rOCUMENT RESUME ED 045 767 UD 011 084 TITLE Education in Israel3 Report of the Select Subcommittee on Education... Ninety-First Congress, Second Session. INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, E.C. House Ccmmittee on Education and Labcr. PUB DATE Aug 70 NOTE 237p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MP-$1.00 BC-$11.95 DESCRIPTORS Acculturation, Educational Needs, Educational Opportunities, *Educational Problems, *Educational Programs, Educational Resources, Ethnic Groups, *Ethnic Relations, Ncn Western Civilization, Research and Development Centers, *Research Projects IDENTIFIERS Committee On Education And Labor, Hebrew University, *Israel, Tel Aviv University ABSTRACT This Congressional Subcommittee report on education in Israel begins with a brief narrative of impressions on preschool programs, kibbutz, vocational programs, and compensatory programs. Although the members of the subcommittee do not want to make definitive judgments on the applicability of education in Israel to American needs, they are most favorably impressed by the great emphasis which the Israelis place on early childhood programs, vocational/technical education, and residential youth villages. The people of Israel are considered profoundly dedicated to the support of education at every level. The country works toward expansion of opportunities for education, based upon a belief that the educational system is the key to the resolution of major social problems. In the second part of the report, the detailed itinerary of the subcommittee is described with annotated comments about the places and persons visited. In the last part, appendixes describing in great depth characteristics of the Israeli education system (higher education in Israel, education and culture, and the kibbutz) are reprinted. (JW) [COMMITTEE PRINT] OF n. -

Maccabi Kiryat Gat Maccabi Kiryat Gat

Maccabi Kiryat Gat Maccabi Kiryat Gat Aktueller Kader Zugänge Nat. Nr. Pos. Name, Vorname Geb. -Datum Letzter Verein im Verein seit Nat. Name, Vorname Letzter Verein Datum 1 T Abarbanel, Neal 19.06.1987 Maccabi Petah Tikva 07.2014 Abarbanel, Neal Maccabi Petah Tikva 07.2014 33 T Zigdon, Yotam 29.06.1989 Maccabi Shaaraim 07.2014 Amos, Rafi Maccabi Herzliya 07.2014 3 A Malka, Ran 28.07.1987 Maccabi Herzliya 07.2014 Arias, David Hapoel Rahat 07.2014 4 A Kedar, Nadav 09.01.1987 Maccabi Beer Sheva 07.2012 Awad, Firas Hapoel Bnei Lod 07.2014 5 A Tiram, David 16.09.1993 SC Kfar Qasem 07.2014 Ayala, Tal Hapoel Marmorek 07.2014 18 A Ifergan, Yaniv 05.06.1986 Beitar Tel Aviv Ramla 07.2014 Ben Shimon, Ran Hapoel Ramat Gan 07.2014 25 A Malka, Avi 28.07.1987 Maccabi Herzliya 07.2014 Biton, Shay SC Beer Sheva 07.2014 7 M Elkabetz, Yogev 05.07.1985 Maccabi Beer Sheva 07.2012 Elkabatz, Meir Hapoel Bnei Lod 07.2014 8 M Zohar, Maor 09.06.1985 Sektzia Ness Ziona 07.2013 Ifergan, Yaniv Beitar Tel Aviv Ramla 07.2014 10 M Moshe, Shlomi 24.05.1983 Ironi Bat Yam 07.2010 Malka, Avi Maccabi Herzliya 07.2014 11 M Ayala, Tal 25.05.1989 Hapoel Marmorek 07.2014 Malka, Ran Maccabi Herzliya 07.2014 12 M Mor, Eden 01.05.1993 SC Ashdod 07.2014 Mor, Eden SC Ashdod 07.2014 14 M Ben Simhon, Lior 05.02.1993 eigene Jugemd 07.2013 Muzaev, Magomed Unbekannt 07.2014 16 M Porat, Gal 26.05.1990 Maccabi Shaaraim 01.2014 Tiram, David SC Kfar Qasem 07.2014 17 M Vaknin, Itzik 07.06.1992 Hapoel Ramat Gan 07.2014 Vaknin, Itzik Hapoel Ramat Gan 07.2014 22 M Moas, Liran 12.01.1986 eigene Jugemd 07.2005 Zigdon, Yotam Maccabi Shaaraim 07.2014 26 M Arias, David 26.11.1986 Hapoel Rahat 07.2014 55 M Cohen, Omri 04.01.1989 Beitar Tel Aviv Ramla 07.2013 99 M Awad, Firas 09.11.1991 Hapoel Bnei Lod 07.2014 Abgänge 9 S Ben Shimon, Ran 23.05.1990 Hapoel Ramat Gan 07.2014 15 S Biton, Shay 15.10.1994 SC Beer Sheva 07.2014 Nat. -

Operation Pillar of Defense 1 Operation Pillar of Defense

Operation Pillar of Defense 1 Operation Pillar of Defense Operation Pillar of Defense Part of Gaza–Israel conflict Iron Dome launches during operation Pillar of Defense Date 14–21 November 2012 Location Gaza Strip Israel [1] [1] 30°40′N 34°50′E Coordinates: 30°40′N 34°50′E Result Ceasefire, both sides claim victory • According to Israel, the operation "severely impaired Hamas's launching capabilities." • According to Hamas, their rocket strikes led to the ceasefire deal • Cessation of rocket fire from Gaza into Israel. • Gaza fishermen allowed 6 nautical miles out to sea for fishing, reduced back to 3 nautical miles after 22 March 2013 Belligerents Israel Gaza Strip • Hamas – Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades • PIJ • PFLP-GC • PFLP • PRC • Al-Aqsa Martyrs' Commanders and leaders Operation Pillar of Defense 2 Benjamin Netanyahu Ismail Haniyeh Prime Minister (Prime Minister of the Hamas Authority) Ehud Barak Mohammed Deif Minister of Defense (Commander of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades) Benny Gantz Ahmed Jabari (KIA) Chief of General Staff (Deputy commander of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades) Amir Eshel Ramadan Shallah Air Force Commander (Secretary-General of Palestinian Islamic Jihad) Yoram Cohen Abu Jamal Director of Israel Security Agency (Shin Bet) (spokesperson of the Abu Ali Mustafa Brigades) Strength Israeli Southern Command and up to 75,000 reservists 10,000 Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades 8,000 Islamic Jihad Unknown for the rest 10,000 Security forces. Casualties and losses 2 soldiers killed. Palestinian figures: 20 soldiers wounded. 55 -

Lintc E UII1 E Final Report

Date Printed: 11/03/2008 JTS Box Number: IFES 5 Tab Number: 32 Document Title: Final Report: lFES Technical Assistance for Municipal Elections in the West Bank Document Date: 1998 Document Country: West Bank and Gaza IFES ID: R01669 -lintC E UII1 E Final Report IFES Technical Assistance for Municipal Elections in the West Bank and Gaza April 1998 written by Amy Hawthorne, Program Officer " for the Middle East and North Africa, IFES USAID Cooperative Agreement #: 294-A-OO-96-90S49-00 This report was made possible by a grant from the United States Agency for International Development. The opinions expressed in the report are those of IFES. Any person is welcome to quote from the report as long as proper attribution is made. F. C/ihon White Resource Center International Foundation for Election Systems '/00 1101 15th Street. NW . V·'o'-""'qlOn, DC 20005 TABLE OF CONTENTS !' -_. Final Activity Report IFES Technical Assistance for Municipal Elections in the West Bank and Gaza StriP. Chapter 1: Executive Summary Chapter 2: Introduction Chapter 3: Background to Municipal Government Elections in the West Bank and Gaza Chapter 4: Project Objectives and Activities Chapter 5: Project Staffing Chapter 6: Major Outstanding Issues Surrounding Municipal Elections Appendices A. Maps of West Bank and Gaza B. List of Municipal Council Areas in the West Bank and Gaza C. The Palestinian Local Government Election Law D. IFES Manual for Municipal Elections . ("Guide for the Planning and Organization of Local Government Elections in the West Bank and Gaza") .... -

Rural Cooperation

JOURNAL OF RURAL COOPERATION Centre international de recherches sur les communautes cooperatives rurales International Research Centre on Rural Cooperative Communities ""~''''YJ ""'1~!) "')'TlP '1pn) 'tlU-C)-"3T1 t!)'1tlTl CIRCOM VOLUME 24 No.2 1996 CIRCOM, International Research Centre on Rural Cooperative Communities was established in September 1965 in Paris. The purpose of the Centre is to provide a framework for investigations and research on problems concerning rural cooperative communities and publication of the results, to coordinate the exchange of information on current research projects and published works, and to encourage the organization of symposia on the problems of cooperative rural communities, as well as the exchange of experts between different countries. Editorial Advisory Board BARRACLOUGH, Prof. Solon, UNRISD, PLANCK, Prof. Ulrich, Universitat Geneva, Switzerland. Hohenheim, Stuttgart, Germany. CERNEA, Prof. Michael, The World POCHET, Dr. Carlos A., Universidad Bank, Washington, DC, USA. Nacional, Heredia, Costa Rica. CRAIG, Prof. Jack, York University, POHORYLES, Prof. Samuel, Tel Aviv Ontario, Canada. University, Israel. DON, Prof. Yehuda, Bar Ban University, SAXENA, Dr. S.K., Markham, Ontario, Ramat Gan, Israel. Canada. FALS BORDA, Prof. Orlando, Punta de SCHIMMERLING, Prof. Hanus, Lanza Foundation, Bogota, Colombia. Agricultural University, Prague, Czech KLATZMANN, Prof. Joseph, Institut Republic. National Agronomique, Paris, France. SCHVARTZER, Prof. Louis, Universidad MARON, Stanley, Kibbutz Maayan Zvi de Buenos Aires, Argentina. and Yad Tabenkin, Ramat Efal, Israel. SMITH, Prof. Louis, University College, NINOMIY A, Prof. Tetsuo, Kanazawa Dublin, Ireland. University, Japan. STAVENHAGEN, Dr. Rodolfo, EI PARIKH, Prof. Gokul 0., Sardar Patel Colegio de Mexico, Mexico. Institute of Economic and Social Research, STROPPA, Prof. Claudio, Universita di Ahmedabad, India. -

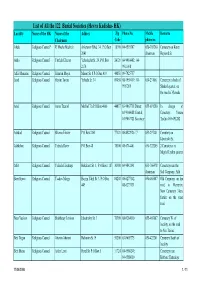

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

A WMD–Free Zone in the Middle East: Regional Perspectives

The Project on Managing the Atom A WMD–Free Zone in the Middle East: Regional Perspectives Paolo Foradori and Martin B. Malin, editors November 2013 Project on Managing the Atom Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Fax: (617) 495-8963 Discussion Paper #2013-09 Copyright 2013 President and Fellows of Harvard College The authors of this discussion paper invite use of this information for educational purposes, requir- ing only that the reproduced material clearly cite the full source: Paolo Foradori and Martin B. Malin, eds., “A WMD-Free Zone in the Middle East: Regional Perspectives.” (Cambridge, Mass.: The Project on Managing the Atom, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard University). November 2013. Statements and views presented in this discussion paper are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsements by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Printed in the United States of America. Cover Photos Upper Left: Members of the UN investigation team take samples from the ground in the Damascus countryside of Zamalka, Syria on August 29, 2013 as part of the on-going process of dismantling Syria’s stockpile of chemical weapons (AP Photo/Local Committee of Arbeen). Upper Right: Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel describes his concerns over Iran’s nuclear ambitions during his address to the United Nations on September 27, 2012 (AP Photo/ Richard Drew). Lower Left: UNITN | © Eyematrix_Images–Fotolia.com, Lower Right: Middle East satellite map from Wikipedia. -

Israeli Water Technology Company Directory™

ISRAELI WATER TECHNOLOGY COMPANY DIRECTORY Compiled by The Negev Foundation Ohio-Israel Ag & CleanTech Initiative 2121 South Green Road Cleveland, OH 44121 216-691-9997 www.ohioisrael.org Ver. 2 – Jan. 2019 Israeli Water Technology Companies 1 A.A. Engineers Environmental & Agricultural Engineering P.O. Box 1360 Services Offered Kiryat Tivon, Israel 36000 +972-4-993-0049 A.A. Engineers is a consulting firm established in 1982 specializing in wastewater treatment, solid waste systems, www.aaengineers.co.il agricultural and environmental consulting. Amitay Avnon, Director They specialize in an environmentally-friendly, biological wastewater treatment system called Constructed Wetlands [email protected] as an ecological solution for sanitary wastewater, industrial and agricultural wastewaters. Admir Environment 24 HaTa'asiya Street Services Offered Yehud, Israel 5621804 +972-3-536-6646 Marine dredging using a DREDGER. Sludge dewatering by means of Geotube®. Fuel tanks and industrial tanks www.admir.co.il cleaning. Sludge dewatering at Municipal WWTP. Rivers clean up and water treatment sedimentation. Hemi Tamari, Marketing Manager [email protected] Israeli Water Technology Companies 2 A.G.M. Communication and Control Ltd. Mitzpe, Services Offered Lower Galilee, 1527600, Israel +972-4-677-4754 / 55 AGM is a provider of smart Communication and Control solutions for SCADA and DCS systems, with 30 years of www.agm.co.il experience in the area of Water /Wastewater, Oil & Gas, Energy and Environmental real-time monitoring and Oran Drach, control. Marketing Manager [email protected] Agrolan Moshav Nov Services Offered Ramat Hagolan 1292100 Israel +972-4-666-6999 Weather stations, storm water management, precision farming, measurement devices, sensors, diagnostic kits, www.agrolan.co.il remote telemetry by cellular, IoT - Internet of Things. -

Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2018 Shifting Priorities? Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism Mohamad Batal Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation Batal, Mohamad, "Shifting Priorities? Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism" (2018). CMC Senior Theses. 1826. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1826 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Shifting Priorities? Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism Submitted To Professor George Thomas by Mohamad Batal for Senior Thesis Spring 2018 April 23, 2018 ii iii iv Abstract: This thesis begins with an explanation of Israel’s foundational constitutional tension—namely, that its identity as a Jewish State often conflicts with liberal- democratic principles to which it is also committed. From here, I attempt to sketch the evolution of the state’s constitutional principles, pointing to Chief Justice Barak’s “constitutional revolution” as a critical juncture where the aforementioned theoretical tension manifested in practice, resulting in what I call illiberal or undemocratic “moments.” More profoundly, by introducing Israel’s constitutional tension into the public sphere, the Barak Court’s jurisprudence forced all of the Israeli polity to confront it. My next chapter utilizes the framework of a bill currently making its way through the Knesset—Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People—in order to draw out the past and future of Israeli civic identity. -

Israel a History

Index Compiled by the author Aaron: objects, 294 near, 45; an accidental death near, Aaronsohn family: spies, 33 209; a villager from, killed by a suicide Aaronsohn, Aaron: 33-4, 37 bomb, 614 Aaronsohn, Sarah: 33 Abu Jihad: assassinated, 528 Abadiah (Gulf of Suez): and the Abu Nidal: heads a 'Liberation October War, 458 Movement', 503 Abandoned Areas Ordinance (948): Abu Rudeis (Sinai): bombed, 441; 256 evacuated by Israel, 468 Abasan (Arab village): attacked, 244 Abu Zaid, Raid: killed, 632 Abbas, Doa: killed by a Hizballah Academy of the Hebrew Language: rocket, 641 established, 299-300 Abbas Mahmoud: becomes Palestinian Accra (Ghana): 332 Prime Minister (2003), 627; launches Acre: 3,80, 126, 172, 199, 205, 266, 344, Road Map, 628; succeeds Arafat 345; rocket deaths in (2006), 641 (2004), 630; meets Sharon, 632; Acre Prison: executions in, 143, 148 challenges Hamas, 638, 639; outlaws Adam Institute: 604 Hamas armed Executive Force, 644; Adamit: founded, 331-2 dissolves Hamas-led government, 647; Adan, Major-General Avraham: and the meets repeatedly with Olmert, 647, October War, 437 648,649,653; at Annapolis, 654; to Adar, Zvi: teaches, 91 continue to meet Olmert, 655 Adas, Shafiq: hanged, 225 Abdul Hamid, Sultan (of Turkey): Herzl Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Jewish contacts, 10; his sovereignty to receive emigrants gather in, 537 'absolute respect', 17; Herzl appeals Aden: 154, 260 to, 20 Adenauer, Konrad: and reparations from Abdul Huda, Tawfiq: negotiates, 253 Abdullah, Emir: 52,87, 149-50, 172, Germany, 279-80, 283-4; and German 178-80,230,