Historical Evaluation of the Delta Waterways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

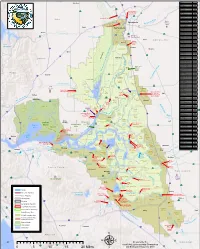

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Proposed Submersed Aquatic Vegetation Treatment Sites for 2017

·|}þ113 80 ¨¦§ 250b ¤£50 ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Proposed Submersed Aquatic Vegetation ¨¦§5 250a Treatment Sites for 2017Yolo ·|}þ84 ·|}þ99 248b 234 232 231 233 230 247a 259 225 247b 224 223 246a 226 222 Sacramento 276 269 246b 220 258a 275 221 258b 219 218 ·|}þ113 279 271 268 257a 280 274 257b 255 ·|}þ160 217 270 265 266 ·|}þ104 278 245 277 256b 216 215 273 264 256a 254 283 267 214 284 282 213a 272 263 262 213b 281 ·|}þ220 253a 244 253b 212a Solano 289 212b ·|}þ84 261 252b 243 211a 208 260 252a 211b 207 288 251a ·|}þ12 251b 242 206 240a 287 241 210a 240b 205 210b San Joaquin ¨¦§5 286 204 140 285 203 209a 209b 200 202 201 20 ·|}þ12 18a 18b 139 22 19a 40 176 21a 21b 19b 36 43 37 17a 44 39 138 41 135 106 17b 35 23b 137 104a 104b 105 38 34 136 23a 175 42 129 160 ·|}þ 103a 16 33 31 128 125 24a 174 103b 107 126 24b 111 173 15 30 123 122 69 32 124 119a 101b 114 29 121a 120a 119b 113 110 171 102 101a 14 121b 120b 117 115 118 116 112 108 ·|}þ4 100 68 13 109 28 99a 26 99b 11 67 65 Site ID Site Name Acres 12 10 98b 8 Atherton Cove 22 97 66 60 8 Duraflame 5 98a 10 Buckley Cove 22 96 59 61 14 Headreach Island 65 95 9 18a Korth's Pirates Lair 13 92b 58 62 8 18a Perry's Boat Harbor 9 92a 57 7 18a Willow Berm 22 91a 94 26 Fourteenmile Slough 41 56 63 ·|}þ4 30 Mosher Slough 36 91b 31 Pixley Slough 65 90a 55 54 53 5 32 Disappointment Slough 284 90b 64 34 Bishop Cut 112 93 52 36 White Slough Upland 23 37 White Slough 196 48 49 47 38 Honker Cut 48 89a 50 4 65 Latham Slough 381 79 Rivers End 11 89b 51 46 87b Kings Island 2 87b 86a 85a 87a,b Italian Slough 11 87a -

Fall 2015 CCSDA Newsletter

Contra Costa Special Districts Association Newsletter Contra Costa Chapter of the California Special Districts Association Fall 2015 October 2015 Ironhouse Sanitary District General Ironhouse new General Manager Manager Tom Williams Retires Chad Davisson, the new General Manager for Ironhouse You don’t have to look too hard to see the changes, Sanitary District (ISD), started on July 13, 2015. Chad innovations and conservation techniques that Tom comes to the District with over 25 years of wastewater Williams has helped bring to Ironhouse Sanitary District industry experience. (ISD) during his 15 years there, including the past 10 as He also has 10 years of general manager. It is those lasting contributions that executive level organization Williams leaves behind. management experience. He has a Bachelor of Arts Congratulations Degree in Public Administration Tom Williams for 15 from San Diego State University and is scheduled to receive his years’ service, ten MBA Degree from Saint Mary’s College in Moraga January years as Manager! 2016. He served as the General Manager of the Richmond First hired as the district’s engineer under the Municipal Sewer District, worked for the City of San leadership of then GM David Bauer, Williams dove in Mateo as the Environmental Services Division Manager, on existing projects around the old treatment plant. the Water Reclamation Systems Plant Manager for When Bauer retired, Williams easily made the transition Olivenhain Water District and the Industrial Waste to overseeing the day-to-day operations of the district. Control Representative for the County of San Diego. One of his first major projects was building a railroad He has also worked as a consultant for Crescent City, undercrossing to safely bring workers and the public the City of Ontario, the City of Montclair and the past what had been a non-signalized grade crossing Olivenhain Municipal Water District. -

CALIFORNIA FISH and GAME ' CONSERVATION of WILDLIFE THROUGH EDUCATION'

REPRINT FROM CALIFORNIA FISH and GAME ' CONSERVATION OF WILDLIFE THROUGH EDUCATION' . VOLUME 50 APRIL 1964 NUMBER 2 ANNUAL ABUNDANCE OF YOUNG STRIPED BASS, ROCCUS SAXATILIS, IN THE SACRAMENTO- SAN JOAQUIN DELTA, CALIFORNIA' HAROLD K. CHADWICK Inland Fisheries Branch California Department of Fish and Game INTRODUCTION A reliable index of striped bass spawning success would serve two important management purposes. First, it would enable us to determine if recruitment is directly related to spawning success. If it is, we could predict important changes in the fishery three years in advance. Second, it would give insight into environmental factors responsible for good and poor year-classes. Besides increasing our understanding of the bass population, this knowledge might be used to improve recruit- ment by modifying water development plans in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta under the State Water Resources Development System. Fyke net samples provided the earliest information on young bass distribution (Hatton, 1940). They were not promising for estimating abundance, and subsequent sampling of eggs and larvae with plankton nets also had important limitations (Calhoun and Woodhull, 1948; Cal- houn, Woodhull, and Johnson, 1950). An exploratory survey with tow nets in the early summer of 1947 (Calhoun and Woodhull, 1948) found bass about an inch long dis- tributed throughout the lower Sacramento-San Joaquin River system except in the Sacramento River above Isleton. This suggested the best index of spawning success would be the abundance of bass about an inch long, measured by tow netting. In 1948 and 1949 extensive tow net surveys were made to measure the relative abundance of young bass in the Delta between Rio Vista and Pittsburg (Erkkila et al., 1950). -

22 AUG 2021 Index Acadia Rock 14967

19 SEP 2021 Index 543 Au Sable Point 14863 �� � � � � 324, 331 Belle Isle 14976 � � � � � � � � � 493 Au Sable Point 14962, 14963 �� � � � 468 Belle Isle, MI 14853, 14848 � � � � � 290 Index Au Sable River 14863 � � � � � � � 331 Belle River 14850� � � � � � � � � 301 Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Res- Belle River 14852, 14853� � � � � � 308 cue System (AMVER)� � � � � 13 Bellevue Island 14882 �� � � � � � � 346 Automatic Identification System (AIS) Aids Bellow Island 14913 � � � � � � � 363 A to Navigation � � � � � � � � 12 Belmont Harbor 14926, 14928 � � � 407 Au Train Bay 14963 � � � � � � � � 469 Benson Landing 14784 � � � � � � 500 Acadia Rock 14967, 14968 � � � � � 491 Au Train Island 14963 � � � � � � � 469 Benton Harbor, MI 14930 � � � � � 381 Adams Point 14864, 14880 �� � � � � 336 Au Train Point 14969 � � � � � � � 469 Bete Grise Bay 14964 � � � � � � � 475 Agate Bay 14966 �� � � � � � � � � 488 Avon Point 14826� � � � � � � � � 259 Betsie Lake 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agate Harbor 14964� � � � � � � � 476 Betsie River 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agriculture, Department of� � � � 24, 536 B Biddle Point 14881 �� � � � � � � � 344 Ahnapee River 14910 � � � � � � � 423 Biddle Point 14911 �� � � � � � � � 444 Aids to navigation � � � � � � � � � 10 Big Bay 14932 �� � � � � � � � � � 379 Baby Point 14852� � � � � � � � � 306 Air Almanac � � � � � � � � � � � 533 Big Bay 14963, 14964 �� � � � � � � 471 Bad River 14863, 14867 � � � � � � 327 Alabaster, MI 14863 � � � � � � � � 330 Big Bay 14967 �� � � � � � � � � � 490 Baileys -

RD799 Five Year Plan

Reclamation District 799 Five Year Capital Improvement Plan May 2012 Prepared by 2365 Iron Point Road, Suite 300 Folsom, CA 95630 This page intentionally left blank. RD 799 Five Year Plan Contents 1.0 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 1 2.0 Brief History of Hotchkiss Tract .......................................................................................... 3 2.1 Location .............................................................................................................................................. 3 2.2 Geomorphic Evolution ........................................................................................................................ 4 2.3 Historical Flood Events ....................................................................................................................... 6 2.3.1 Existing level of protection ........................................................................................................... 6 3.0 Identification of Need for Improvements to Alleviate or Minimize Existing Hazards ........................................................................................................................................ 7 3.1 Local Assets ....................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Non-local Assets and Public Benefit .................................................................................................. -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Comparing Futures for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

comparing futures for the sacramento–san joaquin delta jay lund | ellen hanak | william fleenor william bennett | richard howitt jeffrey mount | peter moyle 2008 Public Policy Institute of California Supported with funding from Stephen D. Bechtel Jr. and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation ISBN: 978-1-58213-130-6 Copyright © 2008 by Public Policy Institute of California All rights reserved San Francisco, CA Short sections of text, not to exceed three paragraphs, may be quoted without written permission provided that full attribution is given to the source and the above copyright notice is included. PPIC does not take or support positions on any ballot measure or on any local, state, or federal legislation, nor does it endorse, support, or oppose any political parties or candidates for public office. Research publications reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Directors of the Public Policy Institute of California. Summary “Once a landscape has been established, its origins are repressed from memory. It takes on the appearance of an ‘object’ which has been there, outside us, from the start.” Karatani Kojin (1993), Origins of Japanese Literature The Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta is the hub of California’s water supply system and the home of numerous native fish species, five of which already are listed as threatened or endangered. The recent rapid decline of populations of many of these fish species has been followed by court rulings restricting water exports from the Delta, focusing public and political attention on one of California’s most important and iconic water controversies. -

UC Davis San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science

UC Davis San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science Title Implications for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions and Economics of a Changing Agricultural Mosaic in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99z2z7hb Journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 15(3) ISSN 1546-2366 Authors Deverel, Steven Jacobs, Paul Lucero, Christina et al. Publication Date 2017 DOI 10.15447/sfews.2017v15iss3art2 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California SEPTEMBER 2017 RESEARCH Implications for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions and Economics of a Changing Agricultural Mosaic in the Sacramento – San Joaquin Delta Steven Deverel1, Paul Jacobs2, Christina Lucero1, Sabina Dore1, and T. Rodd Kelsey3 profit changes relative to the status quo. We spatially Volume 15, Issue 3 | Article 2 https://doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2017v15iss3art2 assigned areas for rice and wetlands, and then allowed the Delta Agricultural Production (DAP) * Corresponding author: [email protected] model to optimize the allocation of other crops to 1 HydroFocus, Inc. maximize profit. The scenario that included wetlands 2827 Spafford Street, Davis, CA 95618 USA decreased profits 79% relative to the status quo but 2 University of California, Davis -1 One Shields Ave, Davis, CA 95616 USA reduced GHG emissions by 43,000 t CO2-e yr (57% 3 The Nature Conservancy reduction). When mixtures of rice and wetlands were 555 Capitol Mall Suite 1290, Sacramento, CA 95814 USA introduced, farm profits decreased 16%, and the GHG -1 emission reduction was 33,000 t CO2-e yr (44% reduction). -

Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA

UC Davis San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science Title Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xd4x0xw Journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 8(2) ISSN 1546-2366 Authors Deverel, Steven J Leighton, David A Publication Date 2010 DOI https://doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2010v8iss2art1 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xd4x0xw#supplemental License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California august 2010 Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA Steven J. Deverel1 and David A. Leighton Hydrofocus, Inc., 2827 Spafford Street, Davis, CA 95618 AbStRACt will range from a few cm to over 1.3 m (4.3 ft). The largest elevation declines will occur in the central To estimate and understand recent subsidence, we col- Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. From 2007 to 2050, lected elevation and soils data on Bacon and Sherman the most probable estimated increase in volume below islands in 2006 at locations of previous elevation sea level is 346,956,000 million m3 (281,300 ac-ft). measurements. Measured subsidence rates on Sherman Consequences of this continuing subsidence include Island from 1988 to 2006 averaged 1.23 cm year-1 increased drainage loads of water quality constitu- (0.5 in yr-1) and ranged from 0.7 to 1.7 cm year-1 (0.3 ents of concern, seepage onto islands, and decreased to 0.7 in yr-1). Subsidence rates on Bacon Island from arability. -

California Regional Water Quality Control Board Central Valley Region Karl E

California Regional Water Quality Control Board Central Valley Region Karl E. Longley, ScD, P.E., Chair Linda S. Adams Arnold 11020 Sun Center Drive #200, Rancho Cordova, California 95670-6114 Secretary for Phone (916) 464-3291 • FAX (916) 464-4645 Schwarzenegger Environmental http://www.waterboards.ca.gov/centralvalley Governor Protection 18 August 2008 See attached distribution list DELTA REGIONAL MONITORING PROGRAM STAKEHOLDER PANEL KICKOFF MEETING This is an invitation to participate as a stakeholder in the development and implementation of a critical and important project, the Delta Regional Monitoring Program (Delta RMP), being developed jointly by the State and Regional Boards’ Bay-Delta Team. The Delta RMP stakeholder panel kickoff meeting is scheduled for 30 September 2008 and we respectfully request your attendance at the meeting. The meeting will consist of two sessions (see attached draft agenda). During the first session, Water Board staff will provide an overview of the impetus for the Delta RMP and initial planning efforts. The purpose of the first session is to gain management-level stakeholder input and, if possible, endorsement of and commitment to the Delta RMP planning effort. We request that you and your designee attend the first session together. The second session will be a working meeting for the designees to discuss the details of how to proceed with the planning process. A brief discussion of the purpose and background of the project is provided below. In December 2007 and January 2008 the State Water Board, Central Valley Regional Water Board, and San Francisco Bay Regional Water Board (collectively Water Boards) adopted a joint resolution (2007-0079, R5-2007-0161, and R2-2008-0009, respectively) committing the Water Boards to take several actions to protect beneficial uses in the San Francisco Bay/Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Estuary (Bay-Delta).