Remembering in Jazz: Collective Memory and Collective Improvisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio's

Musical and Literary Quotations in the Third Movement of Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia Richard Lee-Thai 30024611 MUSI 333: Late Romantic and Modern Music Dr. Freidemann Sallis Due Date: Friday, April 6th 1 | P a g e Luciano Berio (1925-2003) is an Italian composer whose works have explored serialism, extended vocal and instrumental techniques, electronic compositions, and quotation music. It is this latter aspect of quotation music that forms the focus of this essay. To illustrate how Berio approaches using musical and literary quotations, the third movement of Berio’s Sinfonia will be the central piece analyzed in this essay. However, it is first necessary to discuss notable developments in Berio’s compositional style that led up to the premiere of Sinfonia in 1968. Berio’s earliest explorations into musical quotation come from his studies at the Milan Conservatory which began in 1945. In particular, he composed a Petite Suite for piano in 1947, which demonstrates an active imitation of a range of styles, including Maurice Ravel, Sergei Prokofiev and the neoclassical language of an older generation of Italian composers.1 Berio also came to grips with the serial techniques of the Second Viennese School through studying with Luigi Dallapiccola at the Tanglewood Music Festival in 1952 and analyzing his music.2 The result was an ambivalence towards the restrictive rules of serial orthodoxy. Berio’s approach was to establish a reservoir of pre-compositional resources through pitch-series and then letting his imagination guide his compositional process, whether that means transgressing or observing his pre-compositional resources. This illustrates the importance that Berio’s places on personal creativity and self-expression guiding the creation of music. -

2015 Regional Music Scholars Conference Abstracts Friday, March 27 Paper Session 1 1:00-3:05

2015 REGIONAL MUSIC SCHOLARS CONFERENCE A Joint Meeting of the Rocky Mountain Society for Music Theory (RMSMT), Society for Ethnomusicology, Southwest Chapter (SEMSW), and Rocky Mountain Chapter of the American Musicological Society (AMS-RMC) School of Music, Theatre, and Dance, Colorado State University March 27 and 28, 2015 ABSTRACTS FRIDAY, MARCH 27 PAPER SESSION 1 1:00-3:05— NEW APPROACHES TO FORM (RMSMT) Peter M. Mueller (University of Arizona) Connecting the Blocks: Formal Continuity in Stravinsky’s Sérénade en La Phrase structure and cadences did not expire with the suppression of common practice tonality. Joseph Straus points out the increased importance of thematic contrast to delineate sections of the sonata form in the beginning of the nineteenth century. Igor Stravinsky exploited other musical elements (texture, range, counterpoint, dynamics, etc.) to delineate sections in his neoclassical works. While theorists have introduced large-scale formal approaches to Stravinsky’s works (block juxtaposition, stratification, etc.), this paper presents an examination of smaller units to determine how they combine to form coherence within and between blocks. The four movements of the Sérénade present unique variations of phrase construction and continuity between sections. The absence of clear tonic/dominant relationships calls for alternative formal approaches to this piece. Techniques of encirclement, enharmonic ties, and rebarring reveal methods of closure. Staggering of phrases, cadences, and contrapuntal lines aid coherence to formal segments. By reversing the order of phrases in outer sections, Stravinsky provides symmetrical “bookends” to frame an entire movement. Many of these techniques help to identify traditional formal units, such as phrases, periods, and small ternary forms. -

Musical Notations 3

F.A.P. May/June 1971 Musical Notations on Stamps: Part 3 By J. Posell Since my last article on this subject which appeared in FAP Journals (Vol. 14, 4 and 5), a number of stamps have been issued with musical notation which have aroused considerable interest and curiosity. Rather than waiting the five year period which I promised our readers, I have been prevailed upon to compile a listing of these issues now. Some of the information contained here has already been sent to different collectors who made inquiries of me; some of it has already appeared in print. However, it seems appropriate to include it all under one roof again and so I beg the indulgence of my friends who may find some of this reading repetitious. AJMAN Scott ??? Michel 427 A This issue was described in detail by this writer in the Western Stamp Collector for 16 May 1970. The issue consists of four stamps and a souvenir sheet all issued both perforated and imperforate. The imperforate stamps include the musical quotation both at top and bottom plus a picture of a violin in the border at right. The notation is strangely incorrect on all issues. The following information is extracted from the above article. The music on the Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) stamp is the opening chorale from the St. Matthew Passion (Ah dearest Jesu), Bach's most famous oratorio. This is originally written in the key of B minor but on the stamp it has been transposed down to the key of G minor. -

Aaron Copland (1910-90), and Charles Ives (1874-1954) – December 11, 2017

AAP: Music American nostalgia: Samuel Barber (1910-81), Aaron Copland (1910-90), and Charles Ives (1874-1954) – December 11, 2017 Aaron Copland • Parents immigrated to the US and opened a furniture store in Brooklyn • Youngest of five children • Began studying piano at age 13 • Studied in Paris with Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979) • The school of music at CUNY Queens College is named after him: Aaron Copland School of Music Career: • Composed – musical style incorporates Latin American (Brazilian, Cuban, Mexican), Jewish, Anglo-American, and African-American (jazz) sources • Conducted (1958-78) • Wrote essays about music • Visiting teaching positions (New School for Social Research, Henry Street Settlement, Harvard University) • Public lectures (Harvard’s Norton Professor of Poetics, 1951-52) Copland organized concerts that promoted the music of his peers: Marc Blitzstein (1905-64) Roy Harris (1898-1979) Paul Bowles (1910-99) Charles Ives (1874-1954) Henry Brant (1913-2008) Walter Piston (1894-1976) Carlos Chávez (1899-1978) Carl Ruggles (1876-1971) Israel Citkowitz (1909-74) Roger Sessions (1896-1985) Vivian Fine (1913-2000) Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) Copland was a mentor to younger composers: Leonard Bernstein (1918-90) Irving Fine (1914-62) David del Tredici (b. 1937) Lukas Foss (1922-2009) David Diamond (1915-2005) Barbara Kolb (b. 1939) Jacob Druckman (1928-96) William Schuman (1910-92) Elliott Carter (1908-2012) AAP: Music Selected works Orchestra Ballets (also published as orchestral suites) Music for the Theatre (1925) Billy the Kid -

Defining Instrumental Collage Music in Tempered Confetti and Venni, Viddi

TEMPERED CONFETTI: DEFINING INSTRUMENTAL COLLAGE MUSIC IN TEMPERED CONFETTI AND VENNI, VIDDI, – Andrew Campbell Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2016 APPROVED: Panayiotis Kokoras, Major Professor Jon Nelson, Committee Member Joseph Klein, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Music Composition John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Vice Provost of the Toulouse Graduate School Campbell, Andrew S. Tempered Confetti: Defining Instrumental Collage Music in Tempered Confetti and Venni, Viddi, –. Master of Arts (Composition), August 2016, 83 pp., 4 figures, 9 examples, bibliography, 40 titles. This thesis explores collage music's formal elements in an attempt to better understand its various themes and apply them in a workable format. I explore the work of John Zorn; how time is perceived in acoustic collage music and the concept of "super tempo"; musical quotation and appropriation in acoustic collage music; the definition of acoustic collage music in relation to other acoustic collage works; and musical montages addressing the works of Charles Ives, Lucciano Berio, George Rochberg, and DJ Orange. The last part of this paper discusses the compositional process used in the works Tempered Confetti and Venni, Viddi, – and how all issues of composing acoustic collage music are addressed therein. Copyright 2016 by Andrew Campbell ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................v -

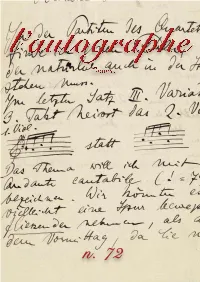

Genève L'autographe

l’autographe Genève l'autographe L’Autographe S.A. 24 rue du Cendrier, CH - 1201, Genève +41 22 510 50 59 (mobile) +41 22 523 58 88 (bureau) web: www.lautographe.com mail: [email protected] All autographs are offered subject to prior sale. Prices are quoted in US DOLLARS, SWISS FRANCS and EUROS and do not include postage. All overseas shipment will be sent by air. Orders above € 1000 benefits of free shipping. We accept payments via bank transfer, PayPal, and all major credit cards. We do not accept bank checks. Postfinance CCP 61-374302-1 3 rue du Vieux-Collège CH-1204, Genève IBAN: EUR: CH94 0900 0000 9175 1379 1 CHF: CH94 0900 0000 6137 4302 1 SWIFT/BIC: POFICHBEXXX paypal.me/lautographe The costs of shipping and insurance are additional. Domestic orders are customarily shipped via La Poste. Foreign orders are shipped with La Poste and Federal Express on request. 1. Richard Adler (New York City, 1921 - Southampton, 2012) Autograph dedication signed on the frontispiece of the musical score of the popular song “Whatever Lola Wants” from the musical comedy “Damn Yankees” by the American composer and producer of several Broadway shows and his partner Jerry Ross. 5 pp. In fine condition. Countersigned with signature and dated “6/2/55” by the accordionist Muriel Borelli. $ 125/Fr. 115/€ 110 2. Franz Allers (Carlsbad, 1905 - Paradise, 1995) Photo portrait with autograph dedication and musical quotation signed, dated June 1961 of the Czech born American conductor of ballet, opera and Broadway musicals. (8 x 10 inch.). In fine condition. -

Fifty-Eighth National Conference November 5–7, 2015 JW Marriott Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana

Fifty-Eighth National Conference November 5–7, 2015 JW Marriott Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana ABSTRACTS & PROGRAM NOTES updated October 30, 2015 Abeles, Harold see Ondracek-Peterson, Emily (The End of the Conservatory) Abeles, Harold see Jones, Robert (Sustainability and Academic Citizenship: Collegiality, Collaboration, and Community Engagement) Adams, Greg see Graf, Sharon (Curriculum Reform for Undergraduate Music Major: On the Implementation of CMS Task Force Recommendations) Arnone, Francesca M. see Hudson, Terry Lynn (A Persistent Calling: The Musical Contributions of Mélanie Bonis and Amy Beach) Bailey, John R. see Demsey, Karen (The Search for Musical Identity: Actively Developing Individuality in Undergraduate Performance Students) Baldoria, Charisse The Fusion of Gong and Piano in the Music of Ramon Pagayon Santos Recipient of the National Artist Award, Ramón Pagayon Santos is an icon in Southeast Asian ethnomusicological scholarship and composition. His compositions are conceived within the frameworks of Philippine and Southeast Asian artistic traditions and feature western and non- western elements, including Philippine indigenous instruments, Javanese gamelan, and the occasional use of western instruments such as the piano. Receiving part of his education in the United States and Germany (M.M from Indiana University, Ph. D. from SUNY Buffalo, studies in atonality and serialism in Darmstadt), his compositional style developed towards the avant-garde and the use of extended techniques. Upon his return to the Philippines, however, he experienced a profound personal and artistic conflict as he recognized the disparity between his contemporary western artistic values and those of postcolonial Southeast Asia. Seeking a spiritual reorientation, he immersed himself in the musics and cultures of Asia, doing fieldwork all over the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia, resulting in an enormous body of work. -

The Rise in Sonatas and Suites for Unaccompanied Viola, 1915-1929 Introduction Ladislav Vycpálek’S Suite for Solo Viola, Op

UNIVERISTY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara The Viola Stands Alone: The Rise in Sonatas and Suites for Unaccompanied Viola, 1915-1929 A document submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Music by Jacob William Adams Committee in charge: Professor Helen Callus, Chair Professor Derek Katz Professor Paul Berkowitz December 2014 The document of Jacob William Adams is approved. Paul Berkowitz Derek Katz Helen Callus, Committee Chair ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research and writing would not have been possible without tremendous support and encouragement from several important people. Firstly, I must acknowledge the UCSB faculty members that comprise my committee: Helen Callus, Derek Katz, and Paul Berkowitz. All three have provided invaluable guidance, constructive feedback, and varied points of view to consider throughout the researching and writing process, and each of them has contributed significantly to my development as a musician-scholar. Beyond my committee members, I want to thank Carly Yartz, David Holmes, Tricia Taylor, and Patrick Chose. These various staff members of the UCSB Music Department have provided much needed assistance throughout my tenure as a graduate student in the department. Finally, I would like to dedicate this manuscript to my parents, David and Martha. They instilled a passion for music and an intellectual curiosity early and often in my life. They helped me see the connections in things all around me, encouraged me to work hard and probe deeper, and to examine how seemingly disparate things can relate to one another or share commonalities. It is thanks to them and their never-ending love and support that I have been able to accomplish what I have. -

Memory and Aesthetics: Study of Musical Quotations in Ives's and Crumb's Music

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, June 2018, Vol. 8, No. 6, 852-879 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2018.06.005 D DAVID PUBLISHING Memory and Aesthetics: Study of Musical Quotations in Ives’s and Crumb’s Music LEUNG Tai-wai David Independant Scholar, Hong Kong China Throughout Western music history, pre-existing material has long been the aesthetic core of a new composition. Yet there has never been such an epoch as our time in which using pre-existing material, melodic quotation in particular, features so extensively in works of many of the composers. The aim of this paper is to investigate how the use of quoted tunes in a musical piece operates in an interwoven complex where time and space are of the essence. A quote is able to oscillate perpetually between one’s mental worlds of the memorable past and the imaginative present when it is highlighted enough to be recognizable from its surrounding context. Upon interpreting the use of quotation in various contexts, the aesthetic object, I argue, is the shift from original to quoted music, and vice versa. And listeners can respond aesthetically to the quotation itself even without knowledge of its provenance and textual or referential content. Keywords: aesthetics, collage, emotional response, flashback, imaginary world, memory, metaphor, musical borrowing, melodic quotation, quoted tune, real world, stream-of-consciousness, temporal level Introduction How is memory turned into art? For some, the process is almost spontaneous. A stroll in the meadows easily sparked the most spectacular sound picture in Ives’ orchestral set. A sail across the lake soon occasioned the opening of one of the most ambitious of all Mahler’s symphonic music. -

The Ice Blink Composition and Quotational Thought by Donal Mckenna a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement

The Ice Blink Composition and Quotational Thought by Donal McKenna A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Bachelor of Arts (Major) The Colorado College May 6, 2021 Approved by ___________________________________ Date_____________________ Ofer Ben-Amots ___________________________________ Date___May 7, 2021________ Ryan Raul Bañagale McKenna 2 Every quotation—whether musical or not—has two distinct perspectives apart from that of the original passage. There is the side of the composer that uses a quotation, and there is the audience interpretation of that quotation. Each perspective has its own benefits in conceptualizing how the functions of music work.1 For the composer, quotation becomes a powerful method for invention and participation within a style or a tradition of music. It can even create dialogue between multiple styles and motifs. With a musical quotation, a composer can say something about past music without words. Most importantly, one can use quotation as a lens to help create an original composition. For the second perspective, the audience, quotation morphs into something more abstract. Whether or not a person recognizes something as quotation drastically changes its interpretation. Similar to how quotation for a composer may elaborate on music practices, the unfathomable number of ways an audience can understand quotation helps one expand on the nature of how people discern meaning in music. The analyses of these perspectives depend on a central idea— that quotation unfolds in the way music unfolds. Once the nature of quotation and its relationship to music becomes clear, we can dive into how one might use a lens of quotation to approach problems in composition and in music interpretation. -

I. Introduction 1 Ii. the Construction of Music Copyright: Sampling, Postmodernity and Legal Views of Musical Borrowing 2 A

FROM J.C. BACH TO HIP HOP: MUSICAL BORROWING, COPYRIGHT AND CULTURAL CONTEXT I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE CONSTRUCTION OF MUSIC COPYRIGHT: SAMPLING, POSTMODERNITY AND LEGAL VIEWS OF MUSICAL BORROWING 2 A. COPYRIGHT, MUSIC AND TECHNOLOGY IN THE INTANGIBLES PARADIGM 2 B. FROM BACH V. LONGMAN TO BRIDGEPORT MUSIC: MUSIC COPYRIGHT AND HIP HOP MUSIC 3 1. The Inexact Fit of Copyright for Music 3 2. Hip Hop as Musical and Cultural Phenomenon 4 3. Copyright Doctrine and Hip Hop Music : Situating Hip Hop in Copyright Law 5 C. DICHOTOMIES AND CONTINUITIES: REPRESENTING THE “OTHER” IN MUSIC COPYRIGHT LAW 10 III. MUSICAL COMPOSITION AND MUSICAL BORROWING: MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP IN HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE 12 A. CANONIC CLASSICAL MUSIC: THE HISTORICAL SPECIFICITY OF VISIONS OF MUSICAL COMPOSITION 12 1. Sacralization and Hierarchies of Taste: Aesthetic Value and Musical Composition 13 2. Inventions and Themes: Historicism and the Development of the Classical Canon 16 a. The Classical Music Canon: Development of an Invented Tradition 17 b. Classical Music Practices: Musical Composition and Creativity 21 3. Improvisation and Musical Borrowing by Classical Composers 21 a. Nature and Types of Musical Borrowing 21 b. Borrowing, Improvisation and Commercial Interests 24 B. COMPOSITION AND MUSICAL PRACTICE IN AN AFRICAN AMERICAN TRADITION: CULTURAL ASSUMPTIONS AND MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP 27 1. Creativity in African American Music and Cultural Forms 27 a. Repetition and Revision: Core Features of an African American Aesthetic 28 b. African American Cultural Production and Copyright Standards: Recontextualizing Hip Hop Musical Practices 29 2. The Social Roles and Social Meanings of Music: Context and Living and Museum Traditions 31 IV. -

The Juilliard Manuscript Collection

The Juilliard Manuscript Collection Composer Title Brief Description Arensky, Anton Scherzo, op. 8, for piano Fine autograph manuscript of the “Scherzo” Op. 8 for piano, signed (“Ant. Arensky”), in A major, written in black ink on three systems per page, each of two staves, with deletions, revisions and alterations, some bars represented only by numbers in repeated passages, dedication to Vassily Il’yich Safonov on first page of music. Bach, J. S. Cantata ‘Es ist ein trotzig und The lost manuscript of the transposed continuo part of the cantata ‘Es is ein trotzig und verzagt Ding’ BWV 176 verzagt ding’, BWV 176, from the original set of performing materials for the premiere in Leipzig on 27 May 1725. Bach, J.S. Choräle der Sammlung, Leipzig, 1765 C.P.E. Bach (Chorales from the C.P.E. Bach collection) Bach, J.S. Keyboard music, selections Clavier Übung bestehend in Praeludien… von Johann Sebastian Bach…Directore Chori (Clavier-Übung) Musici Lipsiensis. Opus 1, Leipzig, the author (“In Verlegung des Autoris”), Leipzig, 6 Partitas BWV 825-830 1731 Bach, J.S. St. Matthew Passion and First editions of the “St Matthew Passion” and the “St John Passion” in full score, Berlin, St. John Passion 1830, 1831. Bach, J.S. Kunst der Fuge First Edition, second issue [?], Leipzig, 1752 Barber, Samuel Antony and Cleopatra Autograph musical notebook with directions for cuts and alterations to Act II (sketches) Beethoven, Fidelio Important working manuscript of part of Fidelio, extensively revised by the composer, Ludwig van unsigned, being a scribal manuscript