Bill Cunningham New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Si Beagle Learning Centers Program Volume 32, Number 1 Fall 2017

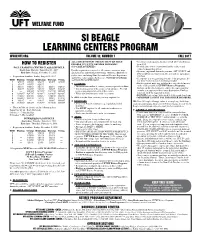

WELFARE FUND SI BEAGLE LEARNING CENTERS PROGRAM WWW.UFT.ORG VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 FALL 2017 ALL CHECKS/MONEY ORDERS MUST BE MADE • You must send separate checks for Fall 2017 and Interses- HOW TO REGISTER PAYABLE TO UFTWF RETIREE PROGRAMS sion 2018. FALL LEARNING CENTER CLASS SCHEDULE (NO CASH ACCEPTED). • Provide the correct course/seminar/trip code(s) and Start date: Monday, September 11, 2017 course/seminar/trip title(s) Use the registration coupon for all courses, seminars, trips, • Spouses, registered domestic partners, AFT, NYSUT and End date: Friday, November 17, 2017 special events and Defensive Driving. There is a $10 fee for PSC members are wait-listed. Do not enclose a payment • Registration deadline: Friday, August 18, 2017 each course, including Dine Around and Theater Experience for them. and $2 for each seminar. All fees are NON-REFUNDABLE • If a spouse is not registering for any of the programs, do WEEK Mondays Tuesdays Wednesdays Thursdays Fridays and NON-TRANSFERABLE. not write his/her name in the line provided. 1 9/11/17 9/12/17 9/13/17 9/14/17 9/15/17 • Each registrant must pay with his/her own checks/money 2 9/18/17 9/19/17 9/20/17 — — v COURSES • The maximum number of courses you may register for is three. order made payable to UFTWF Retiree Programs. 3 9/25/17 9/26/17 9/27/17 9/28/17 9/29/17 Include on the checks/money orders the course number 4 10/2/17 10/3/17 10/4/17 10/5/17 10/6/17 • You must register for the course(s) in advance. -

Rare Manuscripts & Archives

Sale 493 Thursday, November 15, 2012 11:00 AM Rare Manuscripts & Archives Auction Preview Tuesday, November 13, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, November 14, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, November 15, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material. -

A Spike Lee Joints Retrospective, Jun 29—Jul 10

BAMcinématek and the Academy present By Any Means Necessary: A Spike Lee Joints Retrospective, Jun 29—Jul 10 Kicks off with a 25th anniversary screening of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing for Closing Night of BAMcinemaFest with Lee and cast in attendance 15 films in 35mm plus a rare 16mm print of Lee’s debut, Joe’s Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinemaFest, BAMcinématek, and BAM Rose Cinemas. Brooklyn, NY/May 22, 2014—From Sunday, June 29 through Thursday, July 10, BAMcinématek and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences present By Any Means Necessary: A Spike Lee Joints Retrospective, a 12-day series spanning three decades and commemorating the 15th anniversary of BAMcinématek, which launched in 1999 with a survey of Lee’s career. The writer-director-actor’s consistently surprising work displays a boundless visual imagination, some of the most fearlessly intelligent discourse on race relations in American cinema, and an ability to infuse independent projects and big-budget blockbusters alike with his edgy, energetic style. From June 27—July 27, the Academy will also present a west coast retrospective of Lee’s work at the Academy’s Linwood Dunn Theater and the Bing Theater on the Los Angeles County Museum of Art campus. Kicking off the New York retrospective and closing BAMcinemaFest on June 29 is a 25th anniversary celebration of Lee’s Oscar®-nominated Do the Right Thing. The streets of Bed-Stuy boil in Lee’s tale of tensions run high on Brooklyn’s hottest day of the year. -

Fannie Hurst Collection11.Mwalb02040

Fannie Hurst collection11.MWalB02040 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 27, 2021. eng Describing Archives: A Content Standard Brandeis University 415 South St. Waltham, MA URL: https://findingaids.brandeis.edu/ Fannie Hurst collection11.MWalB02040 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 4 Other Descriptive Information ....................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Correspondence ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Fannie Hurst Personal Correspondence ................................................................................................... 5 Correspondence with Organizations ...................................................................................................... -

DO the RIGHT THING (1989) 120 Min

November 28, 2006 XIII: 13 DO THE RIGHT THING (1989) 120 min Produced, Written and Directed by Spike Lee Cinematography by Ernest R. Dickerson Film Editing by Barry Alexander Brown Bill Lee...conductor: The Natural Spiritual Orchestra Branford Marsalis... tenor and soprano saxophone, The Natural Spiritual Orchestra Rosie Perez...choreographer Ossie Davis...Da Mayor Danny Aiello...Sal Giancarlo Esposito...Buggin Out Richard Edson...Vito Spike Lee...Mookie Ruby Dee...Mother Sister Bill Nunn...Radio Raheem John Turturro...Pino Paul Benjamin...ML Rosie Perez...Tina Robin Harris...Sweet Dick Willie Frankie Faison...Coconut Sid SPIKE LEE (20 March 1957, Atlanta, Georgia) has directed Steve White...Ahmad 42 theatrical and tv films, the most recent of which is the Leonard L. Thomas...Punchy HBO documentary on the New Orleans Katrina disaster, Samuel L. Jackson...Mister Señor Love Daddy "When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts" Joie Lee...Jade (2006). Some of the others are “Sucker Free City” (2004), Miguel Sandoval...Officer Ponte She Hate Me (2004), 25th Hour (2002), Come Rain or Rick Aiello...Officer Long Come Shine (2001), Bamboozled (2000), The Original Martin Lawrence...Cee Kings of Comedy (2000), Summer of Sam (1999), He Got Roger Guenveur Smith...Smiley Game (1998), 4 Little Girls (1997), Get on the Bus (1996), John Savage...Clifton Clockers (1995), Crooklyn (1994), Malcolm X (1992), Christa Rivers...Ella Jungle Fever (1991), Mo' Better Blues (1990), Do the Frank Vincent...Charlie Right Thing (1989), School Daze (1988), She's Gotta Have Luis Ramos...Stevie It (1986) Richard Habersham...Eddie Joe's Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads (1983), Sarah Gwen McGee...Louise (1981), The Answer (1980) and Last Hustle in Brooklyn (1977). -

Opening Day Stars on Broadway Springtime In

® 2014 APR MUSEUMS | BROADWAY | DINING | SHOPPING ULTIMATE GUIDE TO NEW YORK CITY YORK NEW TO GUIDE ULTIMATE Hollywood's names biggest Yankee Stadium & Citi Field & Citi Stadium Yankee Outdoor activities for everyone Stars on Broadway on Stars Opening Day Springtime in NYC Springtime NYC Monthly APR2014 NYCMONTHLY.COM VOL. 4 NO.4 B:13.125 in T:12.875 in S:12.75 in B:9.3125 in S:8.9375 in T:9.0625 in KISS Photographed by Danny Clinch, Brooklyn NY 2014 SOHO BOWERY MADISON AVENUE VIEW THE FILM AT JOHNVARVATOS.COM 1902_JV_SS14_NYC_Monthly_DPS_MAR.indd 1 1/17/14 6:07 PM FS:6.125 in FS:6.125 in F:6.4375 in F:6.4375 in 1 1902_JV_SS14_NYC_Monthly_DPS_MAR.indd Saved at 1-17-2014 4:09 PM from Rosina New Mac Pro by Rosina Pang / Rosina Pang Printed At 100% Job info Approvals Fonts & Images Job 1902 Art Director Stephen Fonts Client Varvatos Copywriter Montana Bodoni Seventytwo ITC W01 Bk (Regular) Media Type Adobe InDesign CS5 Account Mgr Eileen Live 12.75 in x 8.9375 in Studio Artist Rosie Images Trim 12.875 in x 9.0625 in Proofreader None JV0719.tif (CMYK; 199 ppi; 75.07%; Yard Bleed 13.125 in x 9.3125 in 2:2. VARVATOS:*SS14:PRODU...IR_DPS_MAR Pub and New York City Monthly Magazine Client Client: Varvatos Folder:Links:JV0719.tif), Varvatos Logo_ Issue Date Spread Legal Legal: None Red_CMYK_2009.eps (122.5%; Yard 2:2. March Issue Notes VARVATOS:*SS14:PRODU...ks:Varvatos Logo_ Red_CMYK_2009.eps) Materials Due 1/21/14 Inks Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black Contents Cover Photo: "Chrysler Building in Cherry Blossom" © David Blaikie. -

Huevos De Serpiente Racismo Y Xenofobia En El Cine

Huevos de serpiente Racismo y xenofobia en el cine 1 2 Huevos de serpiente Racismo y xenofobia en el cine Chema Castiello á g o r a 3 Este trabajo ha sido posible gracias a la ayuda económica de la Fundación Municipal de Cultura y Universidad Popular del Ayuntamiento de Gijón (Asturias). Diseño de portada: Ferran Fernández. © TALASA Ediciones S.L. Queda rigurosamente prohibida sin la autorización escrita de los titulares del «Copyright», bajo sanciones establecidas en las leyes, la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra por cualquier medio o procedimiento, comprendidos la reproducción y el tratamiento informático, y la distribución de ejemplares de ella mediante cualquier alquiler o préstamo públicos. TALASA EDICIONES S.L. c/ San Felipe Neri, 4. 28013 MADRID Telf.: 915 593 082. Fax: 915 470 209. Fax: 915 426 199. e-mail: [email protected] web: www.talasaediciones.com ISBN: 84-88119-88-7 ISBN eBook: 978-84-96266-55-1 Depósito Legal: M-40799-2001. Impreso por: Efca, s.a. 4 Prólogo Javier Maqua Lo que hay: Godard, USA y Castiello Respondió Godard a un entrevistador televisivo que no tendría ningún in- conveniente en que se pasaran por la tele películas malas, si esas películas ma- las no fueran sólo películas estadounidenses, si pusieran películas malas sue- cas, turcas, iraníes, búlgaras, chinas, de Burkina Faso y de Nueva Ginea. Y el entrevistador arguyó que el audímetro demostraba palmariamente que los teles- pectadores preferían las películas malas estadounidenses a cualquier película mala de otro país. He ahí un ejemplo bien claro de la dificultad de lo Otro, de lo Diferente, para abrirse camino. -

Vimeo Link for ALL of Bruce Jackson's and Diane Christian's Film

April 13, 2021 (42:11) Spike Lee: DO THE RIGHT THING (1989,120 min) Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Cast and crew name hyperlinks connect to the individuals’ Wikipedia entries Vimeo link for ALL of Bruce Jackson’s and Diane Christian’s film introductions and post-film discussions in the virtual BFS Vimeo link for our introduction to Do the Right Thing Zoom link for all Spring 2021 BFS Tuesday 7:00 PM post-screening discussions: Meeting ID: 925 3527 4384 Passcode: 820766 Produced, Written and Directed by Spike Lee Cinematography by Ernest R. Dickerson Film Editing by Barry Alexander Brown Music by The Natural Spiritual Orchestra (Bill Lee, conductor; Branford Marsalis, tenor and soprano saxophone) Choreography by Rosie Perez Though widely seen as one of the most important films of 1989, the film was memorably snubbed in the 1990 Spike Lee...Mookie Academy Awards, only garnering nominations for Best Ruby Dee...Mother Sister Actor in a Supporting Role and Best Writing, Screenplay Bill Nunn...Radio Raheem Written Directly for the Screen. It was recognized as a John Turturro...Pino contender for the Palme d’Or at the 1989 Cannes Film Paul Benjamin...ML Festival, however. Selected by the National Film Rosie Perez...Tina Preservation Board for the National Film Registry, 1999 Robin Harris...Sweet Dick Willie Frankie Faison...Coconut Sid Cast Steve White...Ahmad Ossie Davis...Da Mayor Leonard L. Thomas...Punchy Danny Aiello...Sal Samuel L. Jackson...Mister Señor Love Daddy Giancarlo Esposito...Buggin Out Joie Lee...Jade Richard Edson...Vito Miguel Sandoval...Officer Ponte Rick Aiello...Officer Long Lee: DO THE RIGHT THING—2 Martin Lawrence...Cee two Emmy Awards, two Peabody Awards, and the Cannes Roger Guenveur Smith...Smiley Grand Prix. -

SON of the SOUTH Im Verleih Der Busch Media Group

PRESSEHEFT SON OF THE SOUTH Im Verleih der Busch Media Group Ab 26. August 2021 im KINO INHALT CAST & CREW 3 KURZINHALT 4 PRESSENOTIZ 5 REGISSEUR BARRY ALEXANDER BROWN 7 ÜBER DEN FILM BIOGRAPHIEN 10 PRESSESTIMMEN 16 PREMIERE & KINOTOUR 17 KONTAKT 20 2 CAST & CREW Originaltitel SON OF THE SOUTH Laufzeit 105 Minuten Land/Jahr USA 2021 FSK Freigegeben ab 12 Jahren Kinostart: 26. August 2021 Regie: Barry Alexander Brown Cast Lucas Till (Bob Zellner), Lex Scott Davis (Joanne), Lucy Hale (Carol Ann), Cedric the Entertainer (Reverend Abernathy), Julia Ormond (Virginia Durr), Brian Dennehy (J.O. Zellner), Jake Abel (Doc), Sharonne Lanier (Rosa Parks), Nicole Ansari-Cox (Professor Kleiner), Shamier Anderson (Reggie) Drehbuch Barry Alexander Brown (Nach dem Buch „The Wrong Side of Murder Creek” von Bob Zellner und Constance Curry) Kamera John Rosario Schnitt Barry Alexander Brown Musik Steven Argila Produktionsdesign Eloise Stammerjohn Künstlerische Leitung Dane Moore Kostümdesign Michelle Green Produzenten Bill Black, Eve Pomerance, Colin Bates, Stan Erdreich Ausführender Produzent Spike Lee 3 Die Busch Media Group freut sich, das ebenso mitreißende wie hochaktuelle Drama SON OF THE SOUTH bundesweit ins Kino zu bringen. Oscar-Preisträger Spike Lee (Malcom X, BlacKkKlansman) produzierte die packende Verfilmung der wahren Geschichte eines weißen Amerikaners in den Südstaaten, der sich von seinem rassistischen Umfeld lossagt und der schwarzen Bürgerrechtsbewegung anschließt. Regie führte Spike Lees langjähriger Freund und Filmeditor Barry Alexander Brown (Oscar-Nominierung für BlacKkKlansman). KURZINHALT: Es ist das Jahr 1961 – Im amerikanischen Süden ist der Rassismus gegen die schwarze Bevölkerung seit jeher tief verwurzelt. Der junge College-Student Bob (Lucas Till) wuchs in diesem Klima des Hasses auf, noch dazu als Enkel eines berüchtigten Ku-Klux-Klan-Mitglieds. -

Voice and Visibility: How New York City Filmmakers Changed the Narrative of Marginalized Groups on and Off Camera

VOICE AND VISIBILITY: HOW NEW YORK CITY FILMMAKERS CHANGED THE NARRATIVE OF MARGINALIZED GROUPS ON AND OFF CAMERA Commissioned by New York City Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment Authors: Erica Stein, Joshua Glick, Noelle Griffis, Michael Gillespie 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The New York City Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment (MOME) would like to thank the authors of this report: Michael Gillespie, Joshua Glick, Noelle Griffis, Cortland Rankin, and Erica Stein, with added thanks to Erica for managing the project. For the interview sec- tion of the report, MOME would like to thank all the filmmakers and industry personnel who took the time to share their thoughts and stories. MOME would also like to thank Michael Kerbel and Brian Meacham of the Yale Film Study Center, Charles Denson of the Coney Is- land History Project, Marie Roberts of Coney Island USA, Rob Leddy of the Coney Island Film Festival, and the Indiana University Black Film Center/Archive. MOME is grateful to Professor Annette Insdorf of Columbia University for her assistance in conceptualizing the report and building the team of authors. Shira Gans, MOME’s Senior Director of Policy and Programs, is the primary editor and project manager for this report, and the following staff members also contributed: Anna Bessendorf, Policy Analyst; Janet Allon, Associate Commissioner, Marketing & Communications; and Kenneth Ebie, Director of External Affair and Deputy General Counsel. Finally, MOME would like to thank the late Susan Christopherson for her generous guidance in shaping and developing our interview question set and interview procedures. The Mayor’s Office and the authors are indebted to Prof. -

Alfred Scott • Publisher • 156 Fifth Avenue, New York 3

Photo EDITTA SHERMAN 218-4-I9A-53 Alfred Scott • Publisher • 156 Fifth Avenue, New York 3 CARNEGIE HALL — Evenings at 8:30, May 4, 5, 7, 8: Morning 11:00, May 9 INAUGURAL SEASON! (piopA. 112 CENTRAL PARK SOUTH just west of 6th avenue 70 Members, N. Y. Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra SKITCH HENDERSON, Conductor NEXT TO Tj4E HOTEL NAVARRO Gala Opening Night, May 4 — For The U. S. Air Forces Blitzstein — Symphony "The Airborne" TYRONE POWER, Narrator LEHIGH UNIVERSITY GLEE CLUB GEORGE GANZ, Director THE-PARK Other Evenings—ROMBERG, J. STRAUSS, GERSHWIN, TSCHAIKOWSKY May 9, 11:00 A.M. — "Lollypops" — Music For Children FAYE EMERSON PROKOFIEFF — "PETER AND THE WOLF" Tickets at Box Office. Mail Orders Filled Promptly. Send check or money order with self-addressed stamped envelope to New York Pops, Carnegie Hall. Pries: 1st Boxes $4.00 — 2nd Boxes & Parquet $3.40 Dress Circle $1.50 — Balcony $1.00 (Tax Included) Steinway Piano Managing Director: Schuyler Chapin fajinaqiA diedi ÜRnouncAnwiiA APRIL, 1953 ï 19, Sun. 5:30 p.m.—Gala Youth String Concert 21, Tues. 8:30 p.m.—The Philadelphia Orchestra 22, Wed. 12:00 Noon—Dr. Ervin Seale, Church of the Truth 23, Thurs. 8':45 p.m.—The Philharmonic - Symphony ENJOY ACONCERT - ANYTIME ON Society of New York Victor 'W g 24, Fri. 2:30 p.m.—The Philharmonic - Symphony k LATIN RHYTHMS BY THE BOS TON POPS. La Cumparsita (Rodrí g Society of New York guez); Cariosa (Youmans); The » Continental (Magidson-Conrad); Ritual Fire 24, Fri. 8:30 p.m.—Jazz Concert Dance (Falla) g( 22, Wed. -

Untitled Address at the Graduation of the Teachers Institute

The Women Who Reconstructed American Jewish Education, 1910–1965 hbi series on jewish women Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor the hbi series on jewish women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, publishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the hbi Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. the hbi series on jewish women is supported by a generous gift from Dr. Laura S. Schor. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com. Carol K. Ingall, editor, The Women Who Reconstructed American Jewish Education, 1910–1965 Gaby Brimmer and Elena Poniatowska, Gaby Brimmer Harriet Hartman and Moshe Hartman, Gender and American Jews: Patterns in Work, Education, and Family in Contemporary Life Dvora E. Weisberg, Levirate Marriage and the Family in Ancient Judaism Ellen M. Umansky and Dianne Ashton, editors, Four Centuries of Jewish Women’s Spirituality: A Sourcebook Carole S. Kessner, Marie Syrkin: Values Beyond the Self Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Ma^ Phf^gPah ;9EDIJHK9J;:Å :f^kb\Zg C^pbla>]n\Zmbhg *2*)È*2/.