The Ethos of the Historian: the Minutes of Evidence Project, and Lives Lived with Law on the Ground

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Community Protocols for Bankstown Area Multicultural Network

INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY PROTOCOLS FOR BAMN MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Practical protocols for working with the Indigenous Community of South West Sydney 1 Contents RESPECT, ACKNOWLEDGE, LISTEN Practical protocols for working with Indigenous communities in Western Sydney What are protocols? 1. Get To Know Your Indigenous Community Identity Diversity – Different rules for different community groups (there can sometimes be different groups within communities) 2. Consult Indigenous Reference Groups, Steering Committees and Boards 3. Get Permission The Local Community Elders Traditional Owners Ownership Copyright and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property 4. Communicate Language Koori Time Report back and stay in touch 5. Ethics and Morals Confidentiality Integrity and trust 6. Correct Procedures Respect What to call people Traditional Welcome or Welcome to Country Acknowledging Traditional Owners Paying People Indigenous involvement Cross Cultural Training 7. Indigenous Organisations and Western Sydney contacts Major Indigenous Organisations Local Aboriginal Land Councils Indigenous Corporations/Community Organisations Indigenous Council, Community and Arts workers 8. Keywords to Remember 9. Other Protocol Resource Documents 2 What Are Protocols? Protocols can be classified as a set of rules, regulations, processes, procedures, strategies, or guidelines. Protocols are simply the ways in which you work with people, and communicate and collaborate with them appropriately. They are a guide to assist you with ways in which you can work, communicate and collaborate with the Indigenous community of Western Sydney. A wealth of Indigenous protocols documentation already exists (see Section 9), but to date the practice of following them is not widespread. Protocols are also standards of behaviour, respect and knowledge that need to be adopted. You might even think of them as a code of manners to observe, rather than a set of rules to obey. -

Annual Report Contents About Museums Australia Inc

Museums Australia (Victoria) Melbourne Museum Carlton Gardens, Carlton PO Box 385 Carlton South, Victoria 3053 (03) 8341 7344 Regional Freecall 1800 680 082 www.mavic.asn.au 08 annual report Contents About Museums Australia Inc. (Victoria) About Museums Australia Inc. (Victoria) .................................................................................................. 2 Mission Enabling museums and their Training and Professional Development President’s Report .................................................................................................................................... 3 services, including phone and print-based people to develop their capacity to inspire advice, referrals, workshops and seminars. Treasurer’s Report .................................................................................................................................... 4 Membership and Networking Executive Director’s Report ...................................................................................................................... 5 and engage their communities. to proactively and reactively identify initiatives for the benefit of existing and Management ............................................................................................................................................. 7 potential members and links with the wider museum sector. The weekly Training & Professional Development and Member Events ................................................................... 9 Statement of Purpose MA (Vic) represents -

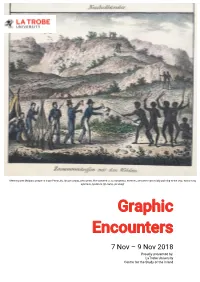

Graphic Encounters Conference Program

Meeting with Malgana people at Cape Peron, by Jacque Arago, who wrote, ‘the watched us as dangerous enemies, and were continually pointing to the ship, exclaiming, ayerkade, ayerkade (go away, go away)’. Graphic Encounters 7 Nov – 9 Nov 2018 Proudly presented by: LaTrobe University Centre for the Study of the Inland Program Melbourne University Forum Theatre Level 1 Arts West North Wing 153 148 Royal Parade Parkville Wednesday 7 November Program 09:30am Registrations 10:00am Welcome to Country by Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin AO 10:30am (dis)Regarding the Savages: a short history of published images of Tasmanian Aborigines Greg Lehman 11.30am Morning Tea 12.15pm ‘Aborigines of Australia under Civilization’, as seen in Colonial Australian Illustrated Newspapers: Reflections on an article written twenty years ago Peter Dowling News from the Colonies: Representations of Indigenous Australians in 19th century English illustrated magazines Vince Alessi Valuing the visual: the colonial print in a pseudoscientific British collection Mary McMahon 1.45pm Lunch 2.45pm Unsettling landscapes by Julie Gough Catherine De Lorenzo and Catherine Speck The 1818 Project: Reimagining Joseph Lycett’s colonial paintings in the 21st century Sarah Johnson Printmaking in a Post-Truth World: The Aboriginal Print Workshops of Cicada Press Michael Kempson 4.15pm Afternoon tea and close for day 1 2 Thursday 8 November Program 10:00am Australian Blind Spots: Understanding Images of Frontier Conflict Jane Lydon 11:00 Morning Tea 11:45am Ad Vivum: a way of being. Robert Neill -

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook

Canadian Official Historians and the Writing of the World Wars Tim Cook BA Hons (Trent), War Studies (RMC) This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW@ADFA 2005 Acknowledgements Sir Winston Churchill described the act of writing a book as to surviving a long and debilitating illness. As with all illnesses, the afflicted are forced to rely heavily on many to see them through their suffering. Thanks must go to my joint supervisors, Dr. Jeffrey Grey and Dr. Steve Harris. Dr. Grey agreed to supervise the thesis having only met me briefly at a conference. With the unenviable task of working with a student more than 10,000 kilometres away, he was harassed by far too many lengthy emails emanating from Canada. He allowed me to carve out the thesis topic and research with little constraints, but eventually reined me in and helped tighten and cut down the thesis to an acceptable length. Closer to home, Dr. Harris has offered significant support over several years, leading back to my first book, to which he provided careful editorial and historical advice. He has supported a host of other historians over the last two decades, and is the finest public historian working in Canada. His expertise at balancing the trials of writing official history and managing ongoing crises at the Directorate of History and Heritage are a model for other historians in public institutions, and he took this dissertation on as one more burden. I am a far better historian for having known him. -

Aboriginal Totems

EXPLORING WAYS OF KNOWING, PROTECTING & ACKNOWLEDGING ABORIGINAL TOTEMS ACROSS THE EUROBODALLA SHIRE FAR SOUTH COAST, NSW Prepared by Susan Dale Donaldson Environmental & Cultural Services Prepared for The Eurobodalla Shire Council Aboriginal Advisory Committee FINAL REPORT 2012 THIS PROJECT WAS JOINTLY FUNDED BY COPYRIGHT AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF INDIGNEOUS CULTURAL & INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS Eurobodalla Shire Council, Individual Indigenous Knowledge Holders and Susan Donaldson. The Eurobodalla Shire Council acknowledges the cultural and intellectual property rights of the Indigenous knowledge holders whose stories are featured in this report. Use and reference of this material is allowed for the purposes of strategic planning, research or study provided that full and proper attribution is given to the individual Indigenous knowledge holder/s being referenced. Materials cited from the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Islander Studies [AIATSIS] ‘South Coast Voices’ collections have been used for research purposes. These materials are not to be published without further consent, which can be gained through the AIATSIS. DISCLAIMER Information contained in this report was understood by the authors to be correct at the time of writing. The authors apologise for any omissions or errors. ACKNOWLEDMENTS The Eurobodalla koori totems project was made possible with funding from the NSW Heritage Office. The Eurobodalla Aboriginal Advisory Committee has guided this project with the assistance of Eurobodalla Shire Council staff - Vikki Parsley, Steve Picton, Steve Halicki, Lane Tucker, Shannon Burt and Eurobodalla Shire Councillors Chris Kowal and Graham Scobie. A special thankyou to Mike Crowley for his wonderful images of the Black Duck [including front cover], to Preston Cope and his team for providing advice on land tenure issues and to Paula Pollock for her work describing the black duck from a scientific perspective and advising on relevant legislation. -

SLSO Aboriginal Communities Homelessness 2 Positions Murwillumbah & Ballina

Aboriginal Child and Family Health Program Coordinator (Health Manager Level 2) Aboriginal Case Worker Temporary Full-Time SLSO Aboriginal Communities Homelessness 2 positions Murwillumbah & Ballina Would you like to make a real difference in people’s lives? If so, come and join the team at Momentum Collective. Momentum Collective is a registered charity and not-for-profit community services organisation. We operate an integrated suite of programs to help our clients get a roof, a job and to live a better life.. This role is in an Aboriginal specific program providing flexible and tailored case management to support housing, wellbeing BLZ_KH0265 and safety to Aboriginal people experiencing or at risk of homelessness. This role offers you the opportunity to be part of an organisation which creates positive and lasting change for people and communities. To apply: please visit our website www.mymomentum.org.au or call Ben Martin on 0407028440 ( Murwillumbah) and Michelle Teece on 0488062245 ( Ballina). BLZ_LP1600 Senior Project Offi cer – Redress Beyond Linking Broken Hill 1x Full Time (35hrs/week) Beyond Linking Team Leader Position Generous leave entitlements + Salary Sacrifice arrangements available The Team Leader will be employed under the conditions of the Social, Community, Home Care and Disability Services Industry Award 2010. Broken Hill Local Aboriginal Land Council, Beyond Linking Program, has a vacancy for 1 full time Beyond Linking Team Leader position to join our team, based in Broken Hill until 30 June 2023. Employment is subject to ongoing funding and satisfactory work performance. Travel is a requirement of the position to deliver the Beyond Linking Program in the Far West Region communities. -

Aboriginal Community Profile Series BULOKE Local Government Area

Aboriginal community profile series BULOKE Local Government Area Overview Population in 2011 35 19 Aboriginal people Median age 6,170 48 non-Aboriginal people Median age Aboriginal organisations Known Traditional Owners Barengi Gadjin Land Council Aboriginal Corporation# Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation# The Life Course Approach Wadi Wadi Wemba Wamba Barapa Barapa First Nations to Aboriginal Affairs in Victoria Aboriginal Corporation Key community groups The Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2013-2018 Northern Loddon Mallee Indigenous Family Violence is the Government’s plan for closing the gap in Victoria Regional Action Group by 2031, working in partnership with Aboriginal Loddon Mallee Regional Aboriginal Justice Advisory communities, service providers and the business sector. Committee As the Aboriginal population in the Buloke Local Loddon Mallee Closing the Health Gap Advisory Government Area (LGA) comprises less than 50 Committee people, this profile is limited to acknowledging Please refer to “Victoria” profile for a list of statewide Aboriginal Aboriginal organisations in the area and organisations, as these may be active in this LGA. Also note there cultural heritage. may be other Aboriginal organisations and community groups which operate in this area. The profile is intended to support conversations #Registered Aboriginal Party covering a specific area within the LGA. between communities, service providers, governments and other key stakeholders. The information can help inform approaches and action at the local level to better meet the needs of Aboriginal people and deliver improved health, education, and employment outcomes. Cultural heritage Buloke LGA Aboriginal people have a deep and continuous connection to the place now called Victoria, evidenced by the number of statewide cultural heritage places. -

Koori Centre Handbook

Koori Centre handbook Set a course for Handbooks online: www.usyd.edu.au/handbooks Acknowledgements Acknowledgements The Arms of the University Sidere mens eadem mutato Though the constellation may change the spirit remains the same Copyright Disclaimers This work is copyright. No material anywhere in this work may be 1. The material in this handbook may contain references to persons copied, reproduced or further disseminated ± unless for private use who are deceased. or study ± without the express and written permission of the legal 2. The information in this handbook was as accurate as possible at holder of that copyright. The information in this handbook is not to be the time of printing. The University reserves the right to make used for commercial purposes. changes to the information in this handbook, including prerequisites for units of study, as appropriate. Students should Official course information check with faculties for current, detailed information regarding Faculty handbooks and their respective online updates, along with units of study. the University of Sydney Calendar, form the official legal source of Price information relating to study at the University of Sydney. Please refer to the following websites: The price of this handbook can be found on the back cover and is in Australian dollars. The price includes GST. www.usyd.edu.au/handbooks www.usyd.edu.au/calendar Handbook purchases You can purchase handbooks at the Student Centre, or online at Amendments www.usyd.edu.au/handbooks All authorised amendments to this handbook -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 350 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to postal submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. AUTHOR THANKS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Climate map data adapted from Peel MC, Anthony Ham Finlayson BL & McMahon TA (2007) ‘Updated Thanks to Maryanne Netto for sending me World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate to such wonderful places – your legacy will Classification’, Hydrology and Earth System endure. To co-authors Trent and Kate who Sciences, 11, 163344. brought such excellence to the book. To David Andrew for so many wise wildlife tips. And to Cover photograph: Loch Ard Gorge, Port every person whom I met along the road – Campbell National Park, David South/Alamy. -

MYLES RUSSELL-COOK William Barak

22 The La Trobe Journal No. 103 September 2019 William Barak, Aboriginal ceremony, blue pigment, ochre and charcoal on cardboard, c. 1880 – c. 1890, Pictures Collection, H29640 William Barak’s paintings at State Library Victoria 23 William Barak, Aboriginal ceremony with wallaby and emu, brown ochre and charcoal on board, c. 1880 – c. 1890, Pictures Collection, H29641 24 MYLES RUSSELL-COOK William Barak Europeans set foot onto Naarm in the first decades of the 19th century. The colony known as Port Phillip District had for millennia been home to the Kulin nation, comprising Wathaurong, Boon Wurrung, Woiwurrung, Taunguerong and Dja Dja Wurrung language groups. They had witnessed the sea level rise, the coast recede; they had seen hills become islands and had witnessed climatic change as the ice age of the Pleistocene epoch ended. Early European settlers failed to recognise the complexity and sophistication of these groups, which lived sustainably on and with their Country. Naarm, which later came to be known as Melbourne, sits on the meeting point of the Birrarung (Yarra River) and its tributaries in the resource-rich lands and waterways of south- east Australia. In June 1835, on the bank of Merri Creek, six kilometres north-east of Melbourne in present-day Northcote, British-born pioneer of Australia John Batman attempted to instigate with the Wurundjeri a treaty which was quickly revoked by colonial officials. Most people now believe that what Batman proposed as a treaty the Kulin recognised as a tanderrum, a ceremony conducted in the south-east permitting access and safe passage to newcomers and strangers, sometimes also called ‘freedom of the bush’. -

Australian Historians and Historiography in the Courtroom

Advance Copy AUSTRALIAN HISTORIANS AND HISTORIOGRAPHY IN THE COURTROOM T ANYA JOSEV* This article examines the fascinating, yet often controversial, use of historians’ work and research in the courtroom. In recent times, there has been what might be described as a healthy scepticism from some Australian lawyers and historians as to the respective efficacy and value of their counterparts’ disciplinary practices in fact-finding. This article examines some of the similarities and differences in those disciplinary practices in the context of the courts’ engagement with both historians (as expert witnesses) and historiography (as works capable of citation in support of historical facts). The article begins by examining, on a statistical basis, the recent judicial treatment of historians as expert witnesses in the federal courts. It then moves to an examination of the High Court’s treatment of general works of Australian history in aid of the Court making observations about the past. The article argues that the judicial citation of historical works has taken on heightened significance in the post-Mabo and ‘history wars’ eras. It concludes that lasting changes to public and political discourse in Australia in the last 30 years — namely, the effect of the political stratagems that form the ‘culture wars’ — have arguably led to the citation of generalist Australian historiography being stymied in the apex court. CONTENTS I Introduction .................................................................................................................. -

Victorian Honour Roll of Women

INSPIRATIONAL WOMEN FROM ALL WALKS OF LIFE OF WALKS ALL FROM WOMEN INSPIRATIONAL VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE I VICTORIAN HONOUR To receive this publication in an accessible format phone 03 9096 1838 ROLL OF WOMEN using the National Relay Service 13 36 77 if required, or email Women’s Leadership [email protected] Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, 1 Treasury Place, Melbourne. © State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services March, 2018. Except where otherwise indicated, the images in this publication show models and illustrative settings only, and do not necessarily depict actual services, facilities or recipients of services. This publication may contain images of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Where the term ‘Aboriginal’ is used it refers to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Indigenous/Koori/Koorie is retained when it is part of the title of a report, program or quotation. ISSN 2209-1122 (print) ISSN 2209-1130 (online) PAGE II PAGE Information about the Victorian Honour Roll of Women is available at the Women Victoria website https://www.vic.gov.au/women.html Printed by Waratah Group, Melbourne (1801032) VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 2018 WOMEN OF ROLL HONOUR VICTORIAN VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE 1 VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE 2 CONTENTS THE 4 THE MINISTER’S FOREWORD 6 THE GOVERNOR’S FOREWORD 9 2O18 VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN INDUCTEES 10 HER EXCELLENCY THE HONOURABLE LINDA DESSAU AC 11 DR MARIA DUDYCZ