Christian and Roman Universalism in the Fourth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

J. N. Adams – P. M. Brennan

J. N. ADAMS – P. M. BRENNAN THE TEXT AT LACTANTIUS, DE MORTIBUS PERSECUTORUM 44.2 AND SOME EPIGRAPHIC EVIDENCE FOR ITALIAN RECRUITS aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 84 (1990) 183–186 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 183 THE TEXT AT LACTANTIUS, DE MORTIBUS PERSECUTORUM 44.2 AND SOME EPIGRAPHIC EVIDENCE FOR ITALIAN RECRUITS At Lact. Mort. 44.2 the transmitted text (C = Codex Colbertinus, BN 2627) runs: 'plus uirium Maxentio erat, quod et patris sui exercitum receperat a Seuero et suum proprium de Mauris atque Italis nuper extraxerat'. Modern editors (Brandt-Laubmann, Moreau, Creed) have accepted Heumann's conjecture G(a)etulis for Italis without discussion.1 But is the change necessary? Much depends on the interpretation of extraxerat. Creed translates… '... his own (army), which he had recently brought over from the Mauri and the Gaetuli' (our italics). In his note (p.118) he finds here an allusion to 'the rebellion against Maxentius of L. Domitius Alexander, vicarius of Africa, which probably began in 308 and was probably crushed by the end of 309'. On this view the troops will have been 'brought over' from Africa after the rebellion was put down. Creed's translation is along the same lines as that of Moreau… I, p.126 'il venait de faire revenir la sienne propre du pays des Maures et des Gétules'.2 In their eagerness to find a reference to L. Domitius Alexander, Moreau and Creed have mistranslated extraxerat. Neither editor attempts to explain how a verb basically meaning 'drag out of' could acquire the sense 'bring over, cause to return'. -

Eirini Artemi National and Capodistrian University of Athens Greece

Dr. Eirini Artemi National and Capodistrian University of Athens Greece International conference commemorating the 1700th Anniversary of the Edict Milan, 31/5/2013- 2/6/2013, Nis of Serbia Emperor Constantine and the theology of Christianity from his autocracy to the second Ecumenical Council ABSTRACT Since his autocracy to his death, Constantine the Great helped the Christianity to be the main religion to all over the empire. This period of time many heresies appeared. They put the unity of Christianity and its teaching in a great danger. Educated people as Arius, Apollinarius, Marcellus, Eunomius and Macedonius tried to explained the nature of God, His actions and His names according to human relationships, their thoughts and their beliefs. The result was a catastrophe, because new heresies were introduced to the Empire. Orthodox Fathers, as Athanasius the Great and Cappadocians Fathers tried to disprove the heresies with success. Upon to these fathers teaching, the First and the Second Ecumenical Councils managed to base their doctrines and to preserve the true teaching and doctrines of Christianity. INTRODUCTION Constantine the Great and his turning to Christianity C. Flavius Valerius Constantinus was born at Naissus, Nis in Serbia. He was the son of Constantius Chlorus, who later became Roman Emperor, and St. Helena, a woman of humble extraction but remarkable character and unusual ability1. Helena was a daughter of an inn keeper. The date of his birth is not certain, being given between 274 and 288. Constantine I or Saint Constantine, was the Roman Emperor since 306 to 337. Well known for being the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity, Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313, which proclaimed religious tolerance of all religions throughout the empire2. -

Constantine the Great and Christian Imperial Theocracy Charles Matson Odahl Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks History Faculty Publications and Presentations Department of History 1-1-2007 Constantine the Great and Christian Imperial Theocracy Charles Matson Odahl Boise State University Publication Information Odahl, Charles Matson. (2007). "Constantine the Great and Christian Imperial Theocracy". Connections: European Studies Annual Review, 3, 89-113. This document was originally published in Connections: European Studies Annual Review by Rocky Mountain European Scholars Consortium. Copyright restrictions may apply. Coda: Recovering Constantine's European Legacy 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 Constantine the Great and Christian Imperial Theocracy Charles Matson Odahl, Boise State University1 rom his Christian conversion under the influence of cept of imperial theocracy was conveyed in contemporary art Frevelatory experiences outside Rome in A.D. 312 until (Illustration I). his burial as the thirteenth Apostle at Constantinople in Although Constantine had been raised as a tolerant 337, Constantine the Great, pagan polytheist and had the first Christian emperor propagated several Olympian of the Roman world, initiated divinities, particularly Jupiter, the role of and set the model Hercules, Mars, and Sol, as for Christian imperial theoc di vine patrons during the early racy. Through his relationship years of his reign as emperor -

Justifying Religious Freedom: the Western Tradition

Justifying Religious Freedom: The Western Tradition E. Gregory Wallace* Table of Contents I. THESIS: REDISCOVERING THE RELIGIOUS JUSTIFICATIONS FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM.......................................................... 488 II. THE ORIGINS OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN EARLY CHRISTIAN THOUGHT ................................................................................... 495 A. Early Christian Views on Religious Toleration and Freedom.............................................................................. 495 1. Early Christian Teaching on Church and State............. 496 2. Persecution in the Early Roman Empire....................... 499 3. Tertullian’s Call for Religious Freedom ....................... 502 B. Christianity and Religious Freedom in the Constantinian Empire ................................................................................ 504 C. The Rise of Intolerance in Christendom ............................. 510 1. The Beginnings of Christian Intolerance ...................... 510 2. The Causes of Christian Intolerance ............................. 512 D. Opposition to State Persecution in Early Christendom...... 516 E. Augustine’s Theory of Persecution..................................... 518 F. Church-State Boundaries in Early Christendom................ 526 G. Emerging Principles of Religious Freedom........................ 528 III. THE PRESERVATION OF RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN MEDIEVAL AND REFORMATION EUROPE...................................................... 530 A. Persecution and Opposition in the Medieval -

The Extension of Imperial Authority Under Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, 285-305Ce

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 The Extension Of Imperial Authority Under Diocletian And The Tetrarchy, 285-305ce Joshua Petitt University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Petitt, Joshua, "The Extension Of Imperial Authority Under Diocletian And The Tetrarchy, 285-305ce" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2412. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2412 THE EXTENSION OF IMPERIAL AUTHORITY UNDER DIOCLETIAN AND THE TETRARCHY, 285-305CE. by JOSHUA EDWARD PETITT B.A. History, University of Central Florida 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2012 © 2012 Joshua Petitt ii ABSTRACT Despite a vast amount of research on Late Antiquity, little attention has been paid to certain figures that prove to be influential during this time. The focus of historians on Constantine I, the first Roman Emperor to allegedly convert to Christianity, has often come at the cost of ignoring Constantine's predecessor, Diocletian, sometimes known as the "Second Father of the Roman Empire". The success of Constantine's empire has often been attributed to the work and reforms of Diocletian, but there have been very few studies of the man beyond simple biography. -

GALERIUS, GAMZIGRAD and the POLITICS of ABDICATION Bill Leadbetter Edith Cowan University

GALERIUS, GAMZIGRAD AND THE POLITICS OF ABDICATION Bill Leadbetter Edith Cowan University /DFWDQWLXV· pamphlet, the de mortibus persecutorum, is a curious survival. In one sense , its subject matter is given lustre by the reputation of the author. Lactantius was a legal scholar and Christian thinker of sufficient prominence, in the early fourth century, to be appointed tutRUWR&RQVWDQWLQH·VHOGHVWVRQ+H was also a polemicist of some wit and great Figure 1: Porphyry head of Galerius savagery. A rhetorican by training, his muse from Gamzigrad drew richly upon the scabrous vocabulary of villainy that seven centuries of speech-making had concocted and perfected. His portrayal of the emperor Galerius in the de mortibus has been influential, if not definitive, for generations of scholars LQWKHVDPHZD\WKDW7DFLWXV· poisonous portrait of Tiberius distorted any analysis of that odd, lonely, angry, bitter and unhappy man (eg: Barnes, 1976, 1981; also Odahl, 2004). /DFWDQLXV· Galerius is not merely bad, he is superlatively bad: the most evil man who ever lived («VHGRPQLEXVTXLfuerunt PDOLVSHLRU«9.1). A vast and corpulent man, he terrified all he encountered by his very demeanour. Despising rank (21.3) and scorning tradition (26.2), /DFWDQWLXV·*DOHULXVLVDERYHDOOIXQGDPHQWDOO\ foreign. Lactantius makes much of his origins as the child of Dacian peasant refugees who settled in the Roman side of the Danube after the Carpi had made Dacia too unpleasant for them (9.4). His Galerius, therefore, is at heart, a barbarian. He is an emperor from beyond the Empire, a monstrous primitive with a savage nature and an alien soul. Lactantius describes him at one point as an enemy of the Romanum nomen and asserts that Galerius intended to change WKHQDPHRIWKH(PSLUHIURP´5RPDQµWR´'DFLDQµ 27.8) and in general was ASCS 31 [2010] Proceedings: classics.uwa.edu.au/ascs31 an enemy of tradition and culture, preferring indeed the company of his pet bears to that of elegant aristocrats and erudite lawyers (21.5-6; 22.4) . -

The Persecution of Licinius

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1999 The persecution of licinius Gearey, James Richard Gearey, J. R. (1999). The persecution of licinius (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/14363 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/25021 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Persecution of Licinius by James Richard Gearey A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF GREEK, LATIN AND ANCIENT HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA JUNE, 1999 Wames Richard Gearey 1999 National Library Biblioth&que nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Sweet 395. me Wellington Ottawa ON K 1A ON4 OltewaON KIAW Canada Canada YarrNI VOV.~ Our im Mr. mIk.nc. The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

The Impact of Constantine the Great's

DOSSIÊ A ANTIGUIDADE TARDIA E SUAS DIVERSIDADES THE EMPEROR AS A ‘MAN OF GOD’: THE IMPACT OF CONSTANTINE THE GREAT’S Conversion on Roman Ideas of Kingship* Harold O Imperador como um “homem de Deus”: O impacto de DRAKE Constantino, o Grande University of California – Conversão nas ideias romanas sobre o reinado USA [email protected] ABSTRACT RESUMO In numerous ways, the first Christian emperor, De várias maneiras, o primeiro imperador cris- Constantine I (r. 306-337) indicated that he saw tão, Constantino I (306-337), indicou as semel- parallels between himself and St. Paul. These hanças que ele via entre si e São Paulo. Nessas include his story of divine intervention (the vi- semelhanças, ele incluiu a sua história de inter- sion of the Cross) and his decision to be bur- venção divina (a visão da Cruz) e a sua decisão ied amid markers for the twelve Apostles. But de ser enterrado em meio as marcas para os his biographer, Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea, doze Apóstolos. Seu biográfo, porém, o Bispo chooses to liken Constantine instead to Mo- Eusébio de Cesaréia, escolhe comparar Con- ses, who led the Israelites out of captivity. By stantino, ao invés de São Paulo, com Moisés, focusing on the different connotation of “Man que liderou os israelitas na saída do cativeiro. of God” (Constantine’s preferred label for him- Focando sobre as diferentes conotações de self) and “Friend of God” (the phrase Eusebius “Homem de Deus” (como Constantino preferiu used), this article suggests that the reason for se definir) e "Amigo de Deus" (termo usado por this difference lay in Eusebius’s concern to pre- Eusébio), este artigo sugere que a razão para vent Constantine – and by extension all future essas diferenças estava na preocupação de Eu- emperors – from asserting priority over Chris- sébio em evitar que Constantino – e por exten- tian bishops. -

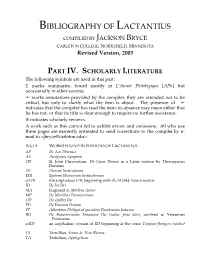

BIBLIOGRAPHY of LACTANTIUS COMPILED by JACKSON BRYCE CARLETON COLLEGE, NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA Revised Version, 2003

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF LACTANTIUS COMPILED BY JACKSON BRYCE CARLETON COLLEGE, NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA Revised Version, 2003 PART IV. SCHOLARLY LITERATURE The following symbols are used in this part: ∑ marks summaries, found mostly in L’Année Philologique [APh] but occasionally in other sources. + marks annotations provided by the compiler; they are intended not to be critical, but only to clarify what the item is about. The presence of + indicates that the compiler has read the item; its absence may mean either that he has not, or that its title is clear enough to require no further assistance. ® indicates scholarly reviews. A work such as this cannot fail to exhibit errors and omissions. All who use these pages are earnestly entreated to send corrections to the compiler by e- mail to <[email protected]>. SIGLA WORKS FOUND IN EDITIONS OF LACTANTIUS AP De Ave Phoenice AS Aenigmata Symposii CD St. John Chrysostom, De Cœna Domini in a Latin version by Hieronymus Donatus DI Divinae Institutiones EDI Epitome Divinarum Institutionum acEDI the acephalous EDI, beginning with ch. 51 [56], Nam si iustitia ID De Ira Dei MA fragment de Motibus Animi MP De Mortibus Persecutorum OD De Opifico Dei PD De Passione Domini PT Adhortatio Philippi ad quendam Theodosium Iudæum RD De Resurrectionis Dominicæ Die (Salve, festa dies), ascribed to Venantius Fotunatus acRD an acephalous version of RD beginning at the verse Tempora florigero rutilant … TS Tertullian, Sermo de Vita Æterna TA Tertullian, Apologeticus J. BRYCE, Bibliography of Lactantius, revised 2003 Part IV. Scholarly Literature 2 VM Lorenzo Valla, De Mystero Eucharistiæ The following subtitles for the seven books of DI are often found: I. -

The Great Altar of Zeus “Satan's Seat”

The Great Altar of Zeus “Satan’s Seat” Balaam could not curse Israel. Only beautiful prophecies filled with blessings flowed from his lips when he was called into Moab by Balak. But Balaam did succeed in leading the Israelites astray through his counsel. The Israelites, through the counsel of Balaam, were led to commit fornication, eat things sacrificed to idols, and bow down before other gods. And because of these sins, the judgment of God fell upon His people. V#14 – But I have a few things against thee, because thou hast there them that hold the doctrine of Balaam, who taught Balac to cast a stumblingblock before the children of Israel, to eat things sacrificed unto idols, and to commit fornication. Stumblingblock – Gk. {skandalon}; occasion to fall The Chi Rho (/ˈkaɪ ˈroʊ/) is one of the earliest forms of christogram, and is used by some Christians. It is formed by superimposing the first two (capital) letters chi and rho (ΧΡ) of the Greek word "ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ" = Christ in such a way to produce the monogram. Although not technically a Christian cross, the Chi-Rho invokes the crucifixion of Jesus, as well as symbolising his status as the Christ.[1] The Chi-Rho symbol was also used by pagan Greek scribes to mark, in the margin, a particularly valuable or relevant passage; the combined letters Chi and Rho standing for chrēston, meaning "good."[2] Some coins of Ptolemy III Euergetes (r. 246–222 BC) were marked with a Chi- Rho.[3] The Chi-Rho symbol was used by the Roman emperor Constantine I as part of a military standard (vexillum), Constantine's standard was known as the Labarum. -

When Did Diocletian Die? Ancient Evidence for an Old Problem

WHEN DID DIOCLETIAN DIE? ANCIENT EVIDENCE FOR AN OLD PROBLEM Mats Waltré 1 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Purpose ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Sources .................................................................................................................................................... 3 And what do contemporary sources tell? ........................................................................................... 5 Recent discussion - 311 or 312? .............................................................................................................. 7 Constantine and Lactantius ................................................................................................................. 7 C.Th. xiii, 10, 2 ..................................................................................................................................... 7 When did Diocletian die? New evidence for an old problem ............................................................. 9 Maxentius and Diocletian .................................................................................................................... 9 Ancient evidence ................................................................................................................................... 10 Lactantius .........................................................................................................................................